Fra Angelico 弗朗切斯科·安杰利科

Early Italian Renaissance painter (c. 1395–1455)

早期意大利文艺复兴画家(约 1395–1455) From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

来自维基百科,自由百科全书

Fra Angelico, O.P. (born Guido di Pietro; c. 1395[1] – 18 February 1455) was a Dominican friar and Italian Renaissance painter of the Early Renaissance, described by Giorgio Vasari in his Lives of the Artists as having "a rare and perfect talent".[2] He earned his reputation primarily for the series of frescoes he made for his own friary, San Marco, in Florence,[3] then worked in Rome and other cities. All his known work is of religious subjects.

弗拉·安杰利科,O.P.(出生名为圭多·迪·皮耶特罗;约 1395 年 [1] – 1455 年 2 月 18 日)是一位多明我会修士和意大利文艺复兴早期的画家,乔尔乔·瓦萨里在他的《艺术家生平》中形容他拥有“罕见而完美的天赋”。 [2] 他主要因在佛罗伦萨的自己的修道院圣马可创作的一系列壁画而声名鹊起, [3] 随后在罗马和其他城市工作。他所有已知的作品都是宗教题材。

Fra Angelico 弗朗切斯科·安杰利科 | |

|---|---|

Posthumous portrait from The Preaching of the Antichrist by Luca Signorelli (c. 1501) in Orvieto Cathedral, Italy 卢卡·西尼奥雷利(约 1501 年)在意大利奥尔维耶托大教堂的《反基督的讲道》中的遗作肖像 | |

| Born 出生 | Guido di Pietro 圭多·迪·彼得罗 c. 1395 |

| Died 去世 | 18 February 1455 (aged about 59) 1455 年 2 月 18 日(约 59 岁) Rome, Papal States 罗马,教皇国 |

| Nationality 国籍 | Italian 意大利语 |

| Known for | Painting, Fresco 绘画,湿壁画 |

| Notable work 显著作品 | Annunciation of Cortona 科尔托纳的报喜堂 Fiesole Altarpiece 菲耶索莱祭坛画 San Marco Altarpiece 圣马可祭坛画 Deposition of Christ 基督的沉积 Niccoline Chapel 尼科利尼教堂 |

| Movement 运动 | Early Renaissance 早期文艺复兴 |

| Patron(s) 赞助人 | Cosimo de' Medici 科西莫·德·美第奇 Pope Eugene IV 教皇尤金四世 Pope Nicholas V 教皇尼古拉五世 |

| Signature 签名 | |

| |

John of Fiesole 费索莱的约翰 | |

|---|---|

| Venerated in 尊敬的 | Catholic Church 天主教会 (Dominican Order) (多米尼加修道会) |

| Beatified 封圣 | 3 October 1982, Vatican City, by Pope John Paul II 1982 年 10 月 3 日,梵蒂冈,由教皇约翰·保罗二世主祭 |

| Major shrine 主要神社 | Santa Maria sopra Minerva, Rome, Italy 圣玛丽亚·索普拉·米涅尔瓦,罗马,意大利 |

| Feast 盛宴 | 18 February 2 月 18 日 |

He was known to contemporaries as Fra Giovanni da Fiesole (Friar John of Fiesole) and Fra Giovanni Angelico (Angelic Brother John). In modern Italian he is called Beato Angelico (Blessed Angelic One);[4] the common English name Fra Angelico means the "Angelic friar".

他在同时代的人中被称为弗拉·乔瓦尼·达·菲耶索莱(Fiesole 的约翰修士)和弗拉·乔瓦尼·安杰利科(天使兄弟约翰)。在现代意大利语中,他被称为贝阿托·安杰利科(Blessed Angelic One); [4] 常见的英文名弗拉·安杰利科意为“天使修士”。

In 1982, Pope John Paul II beatified him[5] in recognition of the holiness of his life, thereby making the title of "Blessed" official. Fiesole is sometimes misinterpreted as being part of his formal name, but it was merely the town where he had taken his vows as a Dominican friar,[6] and would have been used by contemporaries to distinguish him from others with the same forename, Giovanni. He is commemorated by the current Roman Martyrology on 18 February,[7] the date of his death in 1455. There the Latin text reads Beatus Ioannes Faesulanus, cognomento Angelicus—"Blessed John of Fiesole, surnamed 'the Angelic'".

1982 年,教皇约翰·保罗二世为他封圣 [5] ,以表彰他生活的圣洁,从而正式赋予“有福者”这一称号。费索莱有时被误解为他的正式名字的一部分,但这仅仅是他作为多明我修士宣誓的城镇 [6] ,同时也用于当时的人们区分同名的其他人,乔瓦尼。他在现行的罗马殉道者名册中于 2 月 18 日被纪念 [7] ,这是他于 1455 年去世的日期。拉丁文文本写道 Beatus Ioannes Faesulanus, cognomento Angelicus——“有福的费索莱的约翰,绰号‘天使’”。

Vasari wrote of Fra Angelico that "it is impossible to bestow too much praise on this holy father, who was so humble and modest in all that he did and said and whose pictures were painted with such facility and piety."[2]

瓦萨里写道,关于弗拉·安杰利科:“对这位圣父的赞美再多也不为过,他在所做所说的一切中都如此谦逊和谦虚,他的画作则是以如此的轻松和虔诚绘制而成。” [2]

Biography 传记

Early life, 1395–1436 早期生活,1395–1436

Fra Angelico was born Guido di Pietro in the hamlet of Rupecanina[8] in the Tuscan area of Mugello near Fiesole, not far from Florence, towards the end of the 14th century. Nothing is known of his parents. He was baptised Guido. As a child, he was probably known, as was the Italian fashion, as Guidolino ("Little Guido"). The earliest recorded document concerning Fra Angelico dates from 17 October 1417, when he joined a religious confraternity or guild at the Carmine Church, still under the name Guido di Pietro. This record indicates that he was already a painter, as is evident from two records of payment to Guido di Pietro in January and February 1418, for work done in the church of Santo Stefano del Ponte.[9] The first record of Angelico as a friar dates from 1423, the first reference to Fra Giovanni (Friar John), following the custom of those entering one of the older religious orders of taking a new name.[10] He was a member of the convent of Fiesole. The Dominican Order is one of the medieval mendicant Orders. Mendicants generally lived not from the income of estates but from begging or donations. Fra, a contraction of frater (Latin for 'brother'), is a conventional title for a mendicant friar.

弗拉·安杰利科出生于 14 世纪末,名为圭多·迪·皮耶特罗,地点是位于佛罗伦萨附近的费索莱附近的穆杰洛地区的鲁佩卡尼纳小村庄。关于他的父母没有任何资料。他被洗礼时名为圭多。作为孩子,他可能像意大利的习俗一样被称为圭多利诺(“小圭多”)。关于弗拉·安杰利科的最早记录文件日期为 1417 年 10 月 17 日,当时他以圭多·迪·皮耶特罗的名字加入了卡尔米纳教堂的一个宗教兄弟会或公会。这份记录表明他已经是一位画家,从 1418 年 1 月和 2 月对圭多·迪·皮耶特罗的两笔付款记录中可以看出,他在圣斯特凡诺·德尔·庞特教堂完成了工作。关于安杰利科作为修士的第一条记录可追溯到 1423 年,首次提到弗拉·乔瓦尼(修士约翰),这是进入较老宗教秩序的人习惯性地采用新名字的做法。他是费索莱修道院的成员。多明我会是中世纪乞讨修道会之一。乞讨者通常不是依靠地产收入生活,而是依靠乞讨或捐赠。 Fra 是拉丁语“frater”(意为“兄弟”)的缩写,是对乞讨修士的传统称谓。

According to Vasari, Fra Angelico's initial training was as an illuminator, possibly working with his older brother Benedetto, also a Dominican and an illuminator. The former Dominican convent of San Marco in Florence, now a state museum, holds several manuscripts thought to be entirely or partly by his hand.[2] The painter Lorenzo Monaco may have contributed to his art training; the influence of the Sienese school is discernible in his work. He trained also with master Varricho in Milan[11] Despite quite a few moves of the convents where he lived, this did little to constrain his artistic output, which rapidly acquired a reputation. According to Vasari, his first paintings were an altarpiece and a painted screen for the Charterhouse (Carthusian monastery) of Florence. Nothing remains of these today.[2]

根据瓦萨里所述,弗拉·安杰利科的最初训练是作为一名插画师,可能与他的哥哥贝内代托一起工作,后者也是多米尼加人和插画师。位于佛罗伦萨的前多米尼加修道院圣马可现为国家博物馆,保存着几本被认为完全或部分出自他手的手稿。 [2] 画家洛伦佐·摩纳哥可能对他的艺术训练有所贡献;锡耶纳学派的影响在他的作品中显而易见。他还在米兰与大师瓦里奇奥学习过。 [11] 尽管他所居住的修道院经历了多次迁移,但这对他的艺术创作几乎没有限制,他的作品迅速获得了声誉。根据瓦萨里所述,他的第一幅画作是为佛罗伦萨的卡尔图斯修道院创作的祭坛画和一幅画屏。今天这些作品已无存。 [2]

From 1408 to 1418, Fra Angelico was at the Dominican friary of Cortona, where he painted frescoes, mostly now destroyed, in the Dominican Church, and may have been assistant to Gherardo Starnina, or a follower of his.[12] Between 1418 and 1436 he was back in Fiesole, where he executed a number of frescoes for the church and the Fiesole Altarpiece. This was allowed to deteriorate, but has since been restored. A predella of the altarpiece remains intact and is conserved in the National Gallery, London; a great example of Fra Angelico's genius. It shows Christ in Glory surrounded by more than 250 figures, including beatified Dominicans. This period saw the painting of some of his masterpieces, including a version of The Madonna of Humility. This is well preserved and the property of the Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum, on loan to the MNAC of Barcelona. Also completed at this time were an Annunciation and a Madonna of the Pomegranate, at the Prado Museum.

从 1408 年到 1418 年,弗拉·安杰利科在科尔托纳的多米尼加修道院工作,他在多米尼加教堂绘制了大部分现在已被毁坏的壁画,并可能是杰拉尔多·斯塔尔尼纳的助手或追随者。 [12] 在 1418 年到 1436 年期间,他回到菲耶索莱,为教堂和菲耶索莱祭坛画了许多壁画。这些壁画曾被允许恶化,但后来已恢复。祭坛的底座保持完好,现保存在伦敦国家美术馆,是弗拉·安杰利科天才的一个伟大例证。它展示了荣耀中的基督,周围有超过 250 个身影,包括被封圣的多米尼加人。这一时期他创作了一些杰作,包括《谦卑的圣母》的一个版本。这幅画保存完好,属于泰森-博尔内米萨博物馆,借给巴塞罗那的 MNAC。此外,这段时间还完成了《报喜》和《石榴圣母》,现藏于普拉多博物馆。

San Marco, Florence, 1436–1445

圣马可,佛罗伦萨,1436–1445

报喜,约 1440–1445 年

In 1436, Fra Angelico was one of a number of the friars from Fiesole who moved to the newly built convent or friary of San Marco in Florence. This propitious move, placing him at the heart of artistic life of the region, attracted the backing of Cosimo de' Medici. He was one of the wealthiest and most powerful members of the city's governing authority (or "Signoria"), and founder of the dynasty that was set to dominate Florentine politics for much of the Renaissance. Cosimo had a cell reserved for himself at the friary so that he might retreat from the world.

It was, writes Vasari, at Cosimo's urging that Fra Angelico set about the task of decorating the convent, including the magnificent fresco of the Chapter House, the much reproduced Annunciation at the top of the stairs leading to the cells, the Maesta (or Coronation of the Madonna) with Saints (cell 9), and many other devotional frescoes, smaller in format but of a remarkable luminous quality, depicting aspects of the Life of Christ that adorn the walls of each cell.[2]

在 1436 年,弗拉·安杰利科是从菲耶索莱迁移到佛罗伦萨新建的圣马可修道院的一众修士之一。这一有利的举动将他置于该地区艺术生活的中心,吸引了科西莫·德·美第奇的支持。他是城市治理机构(或称“西尼奥里亚”)中最富有和最有权势的成员之一,也是将主导佛罗伦萨政治的大公朝代的创始人。科西莫在修道院为自己预留了一个小房间,以便他可以远离尘世。瓦萨里写道,正是在科西莫的催促下,弗拉·安杰利科开始了装饰修道院的任务,包括壮丽的会议厅壁画、通往小房间楼梯顶部的广为复制的圣报喜画、与圣人一起的《圣母加冕》(第 9 号小房间)以及许多其他小型但具有显著光辉质量的宗教壁画,描绘了基督生平的各个方面,装饰着每个小房间的墙壁。

In 1439 Fra Angelico completed one of his most famous works, the San Marco Altarpiece at Florence. It broke new ground. Not unusual had been images of the enthroned Madonna and Child surrounded by saints, the custom was that the setting looked heaven-like, saints and angels hovering as ethereal presences rather than earthly substance. But in the San Marco Altarpiece, the saints stand squarely within the space, grouped in a natural way as if conversing about their shared witness of the Virgin in glory. This fresh genre, Sacred Conversations, was to underlie major commissions of Giovanni Bellini, Perugino and Raphael.[13]

在 1439 年,弗拉·安吉利科完成了他最著名的作品之一,佛罗伦萨的圣马可祭坛画。这是一项开创性的作品。以往的作品中,圣母与圣婴的形象通常是被围绕在圣人之中,背景看起来像天堂,圣人和天使作为超凡的存在漂浮在空中,而不是具体现实中的存在。但在圣马可祭坛画中,圣人们稳稳地站在空间中,自然地聚集在一起,仿佛在谈论他们共同见证的荣耀中的圣母。这种新颖的类型,神圣对话,成为了乔瓦尼·贝利尼、佩鲁吉诺和拉斐尔等人主要委托作品的基础。

The Vatican, 1445–1455 梵蒂冈,1445–1455

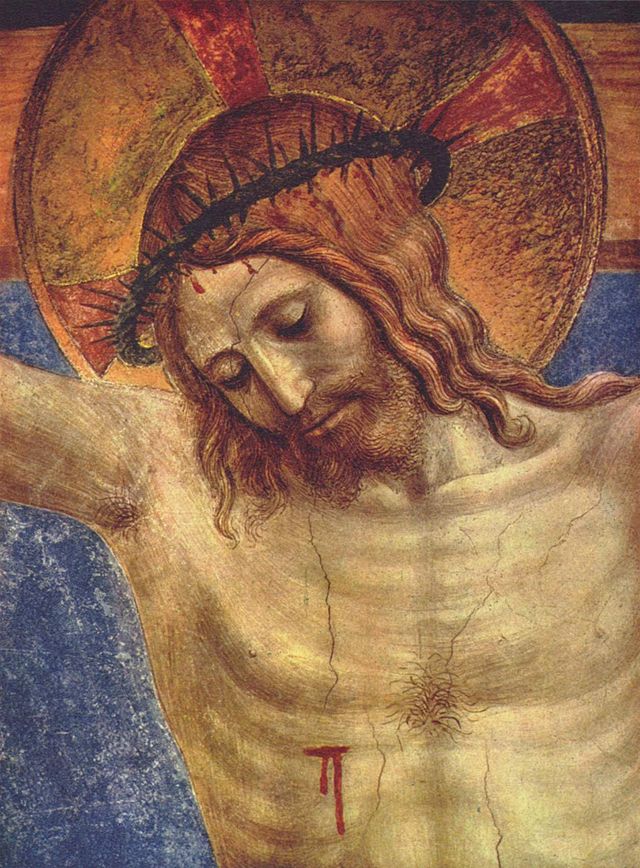

被钉十字架的基督(细节)

In 1445 Pope Eugene IV summoned him to Rome to paint the frescoes of the Chapel of the Holy Sacrament at St Peter's, later demolished by Pope Paul III. Vasari suggests this might have been when Fra Angelico was offered the Archbishopric of Florence by Pope Nicholas V, to turn it down, recommending instead another friar. The story seems possible, and even likely. However, the detail does not tally. In 1445 the pope was Eugene IV. Nicholas was not to be elected until 6 March 1447. The archbishop in question during 1446–1459 was the Dominican Antoninus of Florence (Antonio Pierozzi), canonised by Pope Adrian VI in 1523. In 1447 Fra Angelico was in Orvieto with his pupil, Benozzo Gozzoli, executing works for the Cathedral. Among his other pupils were Zanobi Strozzi.[14]

在 1445 年,教皇尤金四世召唤他到罗马,为圣彼得大教堂的圣餐礼拜堂绘制壁画,后来被教皇保罗三世拆除。瓦萨里建议,这可能是当时教皇尼古拉斯五世向弗拉·安杰利科提供佛罗伦萨大主教职位的时刻,但他拒绝了,推荐了另一位修士。这个故事似乎是可能的,甚至很有可能。然而,细节并不吻合。在 1445 年,教皇是尤金四世。尼古拉斯直到 1447 年 3 月 6 日才被选举。1446 年至 1459 年间的主教是多米尼加修士佛罗伦萨的安东尼乌斯(安东尼奥·皮耶罗齐),于 1523 年被教皇阿德里安六世封圣。在 1447 年,弗拉·安杰利科与他的学生贝诺佐·戈佐利在奥尔维耶托,为大教堂创作作品。他的其他学生包括扎诺比·斯特罗齐。

From 1447 to 1449 Fra Angelico was back at the Vatican, designing the frescoes for the Niccoline Chapel for Nicholas V. The scenes from the lives of the two martyred deacons of the Early Christian Church, St. Stephen and St. Lawrence may have been executed wholly or in part by assistants. The small chapel, with its brightly frescoed walls and gold leaf decorations gives the impression of a jewel box. From 1449 until 1452, Fra Angelico was back at his old convent of Fiesole, where he was the Prior.[2][15]

从 1447 年到 1449 年,佛朗切斯科·安杰利科回到梵蒂冈,为尼古拉斯五世设计尼科利尼小教堂的壁画。早期基督教教会的两位殉道者圣斯德望和圣劳伦斯的生平场景可能完全或部分由助手完成。这个小教堂,墙壁上装饰着明亮的壁画和金箔装饰,给人一种珠宝盒的印象。从 1449 年到 1452 年,佛朗切斯科·安杰利科回到他以前的费索莱修道院,担任院长。

Death and beatification 死亡与封圣

《东方三贤的崇拜》是描绘东方智者到来的场景的圆形画。它被认为是弗拉·安杰利科和菲利波·利皮的作品,创作于大约 1440/1460 年。

In 1455, Fra Angelico died while staying at a Dominican convent in Rome, perhaps on an order to work on Pope Nicholas' chapel. He was buried in the church of Santa Maria sopra Minerva.[2][15][16]

在 1455 年,弗拉·安杰利科在罗马的一座多明我修道院逝世,可能是因为受命为尼古拉斯教皇的教堂工作。他被埋葬在圣玛利亚·索普拉·米内尔瓦教堂。 [2] [15] [16]

When singing my praise, don't liken my talents to those of Apelles.

在赞美我时,不要将我的才能与阿佩利斯的相比。

Say, rather, that, in the name of Christ, I gave all I had to the poor.

说,倒不如说,我以基督的名义,把我所有的一切都给了穷人。The deeds that count on Earth are not the ones that count in Heaven.

在地球上重要的行为并不是在天堂上重要的行为。I, Giovanni, am the flower of Tuscany.

我,乔瓦尼,是托斯卡纳的花。

Apelles (see main article) was a highly renowned painter of Ancient Greece, whose output, now completely lost, is thought to have centred chronologically around 330 BCE.

阿佩列斯(见主条目)是古希腊一位享有盛誉的画家,他的作品现已完全失传,据信其创作时间大约在公元前 330 年左右。

On display near the main altar is a marble tombstone, an exceptional honour for an artist at that time. Two epitaphs were written, probably by Lorenzo Valla. The first reads:

"In this place is enshrined the glory, the mirror, and the ornament of painters, John the Florentine. A religious and a true servant of God, he was a brother of the holy Order of Saint Dominic. His disciples mourn the death of such a great master, for who will find another brush like his? His homeland and his order mourn the death of a distinguished painter, who had no equal in his art." Inside a Renaissance style niche is the painter's relief in Dominican habit. A second epitaph reads:

"Here lies the venerable painter Brother John of the Order of Preachers. May I be praised not because I looked like another Apelles, but because I have offered to you, O Christ, all my wealth. For some, their works survive on earth; for others in heaven. The city of Florence gave birth to me, John."

在主祭坛附近展示着一块大理石墓碑,这是当时艺术家的一个特殊荣誉。两篇墓志铭可能是由洛伦佐·瓦拉撰写的。第一篇写道:“在此地安放着画家的荣耀、镜子和装饰,佛罗伦萨的约翰。他是一位虔诚的宗教人士和上帝的真正仆人,是圣多明哥圣秩的兄弟。他的弟子们为这样一位伟大的大师的去世而哀悼,因为谁能找到像他一样的画笔呢?他的故乡和他的教团为一位在艺术上无与伦比的杰出画家的去世而哀悼。”文艺复兴风格的壁龛内是画家的多明我修士的浮雕。第二篇墓志铭写道:“这里安息着尊敬的画家多明我传教士约翰兄弟。愿我受到赞美,不是因为我像另一个阿佩利斯,而是因为我将我所有的财富都献给了你,基督。对于某些人,他们的作品在世上存活;对于另一些人,则在天堂。佛罗伦萨这座城市孕育了我,约翰。”

The English writer and critic William Michael Rossetti wrote of the friar:

英国作家和评论家威廉·迈克尔·罗塞蒂写道关于修士:

From various accounts of Fra Angelico's life, it is possible to gain some sense of why he was deserving of canonization. He led the devout and ascetic life of a Dominican friar, and never rose above that rank; he followed the dictates of the order in caring for the poor; he was always good-humored. All of his many paintings were of divine subjects, and it seems that he never altered or retouched them, perhaps from a religious conviction that, because his paintings were divinely inspired, they should retain their original form. He was wont to say that he who illustrates the acts of Christ should be with Christ. It is averred that he never handled a brush without fervent prayer and he wept when he painted a Crucifixion. The Last Judgment and the Annunciation were two of the subjects he most frequently treated.[17][15]

从关于弗拉·安杰利科生活的各种记载中,可以感受到他为何值得被封圣。他过着虔诚而禁欲的多米尼加修士生活,从未升迁到更高的职位;他遵循教团的指示,关心穷人;他总是心情愉快。他的许多画作都是神圣主题,似乎他从未对其进行修改或重绘,也许是出于宗教信念,认为他的画作是神灵启发的,应该保持其原始形式。他常说,描绘基督事迹的人应该与基督同在。据说他每次拿起画笔时都要进行热切的祷告,画十字架时会流泪。《最后的审判》和《报喜》是他最常描绘的两个主题。

Pope John Paul II beatified Fra Angelico on 3 October 1982, and in 1984 declared him patron of Catholic artists.[5]

教皇约翰保罗二世于 1982 年 10 月 3 日为安杰利科神父封圣,并于 1984 年宣布他为天主教艺术家的保护神。 [5]

Angelico was reported to say "He who does Christ's work must stay with Christ always". This motto earned him the epithet "Blessed Angelico", because of the perfect integrity of his life and the almost divine beauty of the images he painted, to a superlative extent those of the Blessed Virgin Mary.

安杰利科被报道说过:“做基督工作的必须永远与基督同在。”这个座右铭使他获得了“祝福的安杰利科”这一称号,因为他生活的完美正直和他所绘制的图像几乎具有神圣的美丽,尤其是关于圣母玛利亚的图像。

Evaluation 评估

圣马可,佛罗伦萨,审判日,祭坛画的上部面板。它展示了委托作品所需的精确、细节和色彩。

《提巴德》,展示圣人的生活活动,1420

Background 背景

Fra Angelico was working at a time when the style of painting was in a state of flux. This transformation had begun a century earlier with the works of Giotto and several of his contemporaries, notably Giusto de' Menabuoi. Both had created their major works in Padua, though Giotto had been trained in Florence by the great Gothic artist, Cimabue. He had painted a fresco cycle of St Francis in the Bardi Chapel in the Basilica di Santa Croce. Giotto had many enthusiastic followers, imitating his style in fresco. Some of them, notably the Lorenzetti, achieved great success.[13]

弗拉·安杰利科工作于一个绘画风格处于变革中的时代。这一转变始于一个世纪前,乔托和他的几位同时代人的作品,特别是朱斯托·德·梅纳布伊的作品。两人都在帕多瓦创作了他们的主要作品,尽管乔托是在佛罗伦萨接受伟大的哥特艺术家奇马布埃的训练。他在圣十字大教堂的巴尔迪小教堂绘制了一幅圣方济各的壁画系列。乔托有许多热情的追随者,他们模仿他的壁画风格。其中一些人,特别是洛伦泽蒂,取得了巨大的成功。

Patronage 赞助

If not a monastic establishment, the patron was most usually, as part of a church's endowment, a family with wealth. To maximally advertise this (wealth) favoured subjects where religious devotion would be most focused, an altarpiece for instance. The wealthier the benefactor, the more the style would seem a throwback, compared with a freer and more nuanced style then in vogue. Underpinning this was that a commissioned painting said something about its sponsor: the more gold leaf, the more prestige accrued. Other precious materials in the paint-box were lapis lazuli and vermilion. Paints from these colours lent themselve poorly to a tonal treatment. The azure blue made of powdered lapis lazuli had to be applied flat. As with gold leaf, it was left to the depth and brilliance of colour to announce the patron's importance. This, however, constrained the overall style to that of an earlier generation. Thus, the impression left by altarpieces was more conservative than that achieved by frescoes. These, in contrast, were frequently of almost life-sized figures. To gain effect, they could capitalise on an up-to-date stage-set quality rather than having to fall back upon a lavish, but dated, display.[18]

如果不是修道院,赞助者通常是作为教会捐赠的一部分,拥有财富的家庭。为了最大限度地宣传这种(财富),更倾向于选择宗教虔诚度最集中的主题,例如祭坛画。赞助者越富有,风格看起来就越像是对比当时流行的更自由和更细腻风格的回归。支撑这一点的是,委托的画作在某种程度上反映了其赞助者的身份:金箔越多,积累的声望就越高。其他在调色板中的珍贵材料包括青金石和朱砂。这些颜色的颜料在色调处理上表现不佳。由磨碎的青金石制成的天蓝色必须平涂。与金箔一样,颜色的深度和亮度被用来宣示赞助者的重要性。然而,这限制了整体风格,使其趋向于早期一代的风格。因此,祭坛画所留下的印象比壁画更保守。相比之下,壁画通常描绘的是几乎等身大小的人物。 为了获得效果,他们可以利用现代舞台布景的质量,而不是不得不依赖奢华但过时的展示。 [18]

Contemporaries 当代人

Fra Angelico was the contemporary of Gentile da Fabriano. Gentile's altarpiece of the Adoration of the Magi, 1423, in the Uffizi is regarded as one of the greatest works of the style known as International Gothic. At the time it was painted, another young artist, known as Masaccio, was working on the frescoes for the Brancacci Chapel at the church of the Carmine. Masaccio had fully grasped the implications of the art of Giotto. Few painters in Florence saw his sturdy, lifelike and emotional figures and were not affected by them. His work partner was an older painter, Masolino, of the same generation as Fra Angelico. Masaccio died at 27, leaving the work unfinished.[13]

弗拉·安杰利科是詹蒂莱·达·法布里亚诺的同时代人。詹蒂莱于 1423 年创作的《东方三博士朝拜》祭坛画被认为是国际哥特式风格中最伟大的作品之一。创作时,另一位年轻艺术家马萨乔正在卡尔米纳教堂的布兰卡奇小教堂创作壁画。马萨乔完全领悟了乔托艺术的深远意义。佛罗伦萨的少数画家看到他那坚实、栩栩如生且富有情感的形象时,都受到了影响。他的工作伙伴是同一时代的年长画家马索利诺。马萨乔 27 岁时去世,留下了未完成的作品。

Altarpieces 祭坛画

The works of Fra Angelico reveal elements that are both conservatively Gothic and progressively Renaissance. In the altarpiece of the Coronation of the Virgin, painted for the Florentine church of Santa Maria Novella, are all the elements that a very expensive altarpiece of the 14th century was expected to provide; a precisely tooled gold ground, much azure, and much vermilion. The workmanship of the gilded haloes and gold-edged robes is exquisite and all very Gothic. What makes this a Renaissance painting, as against Gentile da Fabriano's masterpiece, is the solidity, three-dimensionality and naturalism of the figures and the realistic way in which their garments hang or drape around them. Even though it is clouds these figures stand upon, and not the earth, they do so with weight.[13]

弗拉·安杰利科的作品揭示了既保守的哥特式元素又进步的文艺复兴元素。在为佛罗伦萨的圣玛丽亚·诺维拉教堂绘制的《圣母加冕》祭坛画中,包含了 14 世纪非常昂贵的祭坛画所应具备的所有元素;精确加工的金色底面,丰富的天蓝色和朱红色。镀金光环和金边长袍的工艺精湛,完全是哥特式的。与詹蒂莱·达·法布里亚诺的杰作相比,使这幅画成为文艺复兴画作的原因在于人物的坚固性、三维感和自然主义,以及他们的衣物悬挂或垂落的真实方式。尽管这些人物站在云端,而不是在地面上,但他们的姿态却显得沉重。

《变形》展示了这些壁画典型的直接性、简单性和克制的色调。位于圣马可修道院的一个僧侣小室内,其明显的目的是鼓励个人的虔诚。

Frescoes 壁画

The series of frescoes that Fra Angelico painted for the Dominican friars at San Marcos realise the advancements made by Masaccio and carry them further. Away from the constraints of wealthy clients and the limitations of panel painting, Fra Angelico was able to express his deep reverence for his God and his knowledge and love of humanity. The meditational frescoes in the cells of the convent have a quieting quality about them. They are humble works in simple colours. There is more mauvish pink than there is red, and the brilliant and expensive blue is almost totally lacking. In its place is dull green and the black and white of Dominican robes. There is nothing lavish, nothing to distract from the spiritual experiences of the humble people who are depicted within the frescoes. Each one has the effect of bringing an incident of the life of Christ into the presence of the viewer. They are like windows into a parallel world. These frescoes remain a powerful witness to the piety of the man who created them.[13]

Vasari relates that Cosimo de' Medici seeing these works, inspired Fra Angelico to create a large Crucifixion scene with many saints for the Chapter House. As with the other frescoes, the wealthy patronage did not influence the Friar's artistic expression with displays of wealth.[2]

弗朗切斯科·安杰利科为圣马可的多明我修士绘制的一系列壁画体现了马萨乔所取得的进展,并将其进一步发扬光大。远离富裕客户的束缚和面板画的局限,弗朗切斯科·安杰利科能够表达他对上帝的深切敬畏以及对人类的知识和热爱。修道院单人房中的冥想壁画具有一种宁静的特质。它们是简单色彩的谦逊作品。紫红色的调子比红色更多,而明亮而昂贵的蓝色几乎完全缺失。取而代之的是暗绿色和多明我长袍的黑白色。没有奢华的东西,没有任何分散描绘在壁画中的谦卑人们的精神体验的事物。每一幅壁画都能将基督生平的一个事件带入观者的面前。它们就像通往平行世界的窗户。这些壁画仍然是创造它们的人的虔诚的有力见证。 [13] 瓦萨里提到,科西莫·德·美第奇看到这些作品后,激励弗朗切斯科·安杰利科为会议厅创作一幅包含许多圣人的大型十字架场景。 与其他壁画一样,富裕的赞助并没有影响修士的艺术表现,未表现出财富的炫耀。 [2]

Masaccio ventured into perspective with his creation of a realistically painted niche at Santa Maria Novella. Subsequently, Fra Angelico demonstrated an understanding of linear perspective particularly in his Annunciation paintings set inside the sort of arcades that Michelozzo and Brunelleschi created at San' Marco's and the square in front of it.[13]

马萨乔通过在圣玛丽亚诺韦拉创作一个现实主义绘制的壁龛,开始探索透视。随后,弗拉·安杰利科在他的《报喜》画作中展示了对线性透视的理解,画作设置在米开罗佐和布鲁内莱斯基在圣马可和其前广场所创造的拱廊中。

Lives of the Saints

圣人的生活

圣劳伦斯施舍(1447 年),位于梵蒂冈,采用了梵蒂冈委托作品典型的昂贵颜料、金箔和复杂设计。

When Fra Angelico and his assistants went to the Vatican to decorate the chapel of Pope Nicholas, the artist was again confronted with the need to please the very wealthiest of clients. In consequence, walking into the small chapel is like stepping into a jewel box. The walls are decked with the brilliance of colour and gold that one sees in the most lavish creations of the Gothic painter Simone Martini at the Lower Church of St Francis of Assisi, a hundred years earlier. Yet Fra Angelico has succeeded in creating designs which continue to reveal his own preoccupation with humanity, with humility and with piety. The figures, in their lavish gilded robes, have the sweetness and gentleness for which his works are famous. According to Vasari:

当弗拉·安杰利科和他的助手们前往梵蒂冈装饰尼古拉斯教皇的教堂时,这位艺术家再次面临取悦最富有客户的需求。因此,走进这个小教堂就像走进一个珠宝盒。墙壁上装饰着色彩和金光的辉煌,这种辉煌在一百年前的阿西西圣方济各下教堂的哥特画家西蒙·马丁尼的最奢华作品中可以看到。然而,弗拉·安杰利科成功地创造了设计,继续展现他对人性、谦卑和虔诚的关注。这些身着华丽金色长袍的人物,展现了他作品所著名的甜美和温柔。根据瓦萨里:

In their bearing and expression, the saints painted by Fra Angelico come nearer to the truth than the figures done by any other artist.[2]

在姿态和表情上,弗拉·安吉利科所绘的圣人比任何其他艺术家的作品更接近真理。 [2]

It is probable that much of the actual painting was done by his assistants to his design. Both Benozzo Gozzoli and Gentile da Fabriano were highly accomplished painters. Benozzo took his art further towards the fully developed Renaissance style with his expressive and lifelike portraits in his masterpiece depicting the Journey of the Magi, painted in the Medici's private chapel at their palazzo.[19]

很可能实际的绘画工作大部分是由他的助手按照他的设计完成的。贝诺佐·戈佐利和詹蒂莱·达·法布里亚诺都是非常出色的画家。贝诺佐在他的杰作《三贤士的旅程》中将他的艺术进一步推向完全发展的文艺复兴风格,该作品是在美第奇家族的私人教堂中创作的,生动而富有表现力的肖像。 [19]

Artistic legacy 艺术遗产

Through Fra Angelico's pupil Benozzo Gozzoli's careful portraiture and technical expertise in the art of fresco we see a link to Domenico Ghirlandaio, who in turn painted extensive schemes for the wealthy patrons of Florence, and through Ghirlandaio to his pupil Michelangelo and the High Renaissance.

通过弗拉·安杰利科的学生贝诺佐·戈佐利细致的肖像画和壁画艺术的技术专长,我们看到了与多梅尼科·基兰达约的联系,后者为佛罗伦萨的富裕赞助人绘制了大量的作品,而通过基兰达约又联系到他的学生米开朗基罗和高文艺复兴。

Apart from the lineal connection, superficially there may seem little to link the humble priest with his sweetly pretty Madonnas and timeless Crucifixions to the dynamic expressions of Michelangelo's larger-than-life creations. But both these artists received their most important commissions from the wealthiest and most powerful of all patrons, the Vatican.

除了直系关系,表面上看,谦卑的牧师与他那甜美动人的圣母像和永恒的十字架之间似乎没有太多联系,而米开朗基罗的超凡作品则充满了活力。但这两位艺术家都从最富有、最有权势的赞助人——梵蒂冈那里获得了他们最重要的委托。

When Michelangelo took up the Sistine Chapel commission, he was working within a space that had already been extensively decorated by other artists. Around the walls the Life of Christ and Life of Moses were depicted by a range of artists including his teacher Ghirlandaio, Raphael's teacher Perugino and Botticelli. They were works of large scale and exactly the sort of lavish treatment to be expected in a Vatican commission, vying with each other in the complexity of design, number of figures, elaboration of detail and skilful use of gold leaf. Above these works stood a row of painted Popes in brilliant brocades and gold tiaras. None of these splendours have any place in the work which Michelangelo created. Michelangelo, when asked by Pope Julius II to ornament the robes of the Apostles in the usual way, responded that they were very poor men.[13]

当米开朗基罗接受西斯廷教堂的委托时,他在一个已经被其他艺术家广泛装饰的空间内工作。墙壁上描绘了基督的生平和摩西的生平,创作这些作品的艺术家包括他的老师吉尔兰达约、拉斐尔的老师佩鲁吉诺和波提切利。这些作品规模宏大,正是梵蒂冈委托所期待的奢华处理,彼此在设计的复杂性、人物数量、细节的精致程度和金箔的巧妙使用上相互竞争。在这些作品之上,站着一排穿着华丽锦缎和金色王冠的教皇肖像。这些辉煌的作品在米开朗基罗创作的作品中没有任何位置。当教皇朱利乌斯二世要求米开朗基罗以通常的方式装饰使徒的袍子时,他回应说他们是非常贫穷的人。

Within the cells of San'Marco, Fra Angelico had demonstrated that painterly skill and the artist's personal interpretation were sufficient to create memorable works of art, without the expensive trappings of blue and gold. In the use of the unadorned fresco technique, the clear bright pastel colours, the careful arrangement of a few significant figures and the skillful use of expression, motion and gesture, Michelangelo showed himself to be the artistic descendant of Fra Angelico. Frederick Hartt describes Fra Angelico as "prophetic of the mysticism" of painters such as Rembrandt, El Greco and Zurbarán.[13]

在圣马尔科的单元中,弗拉·安杰利科展示了绘画技巧和艺术家的个人解读足以创造出令人难忘的艺术作品,而无需昂贵的蓝色和金色装饰。在使用朴素的壁画技法、明亮的粉彩色彩、少数重要人物的精心安排以及对表情、动作和手势的巧妙运用中,米开朗基罗展现了自己是弗拉·安杰利科的艺术后裔。弗雷德里克·哈特将弗拉·安杰利科描述为“预示着”伦勃朗、埃尔·格列柯和苏尔巴兰等画家的“神秘主义”。

Works 作品

圣母与圣子及圣人,细节,菲索莱(1428–1430)

Early works, 1408–1436 早期作品,1408–1436

Unknown 未知

- Saint James and Saint Lucy Predella, five panels, tempera, c. 1426 to 1428

圣詹姆斯和圣露西底座,五个面板,蛋彩画,约 1426 年至 1428 年

Rome 罗马

- The Crucifixion, panel, c. 1420–1423, Metropolitan Museum, New York.[20] Possibly Fra Angelico's only signed work.[21]

《十字架上的耶稣》,面板,约 1420–1423 年,大都会艺术博物馆,纽约。 [20] 可能是弗拉·安杰利科唯一的签名作品。 [21]

- Annunciation, c. 1430, Diocesan Museum, Cortona

报喜,约 1430 年,教区博物馆,科尔托纳

- Coronation of the Virgin, altarpiece with predellas of Miracles of St Dominic, Church of San Domenico, Louvre, Paris

处女的加冕,带有圣多米尼克奇迹的底座的祭坛画,圣多米尼克教堂,巴黎卢浮宫 - Virgin and Child between Saints Thomas Aquinas, Barnabas, Dominic and Peter Martyr, San Domenico, 1424

圣母与圣子,圣托马斯·阿奎那、圣巴拿巴、圣多米尼克和圣彼得·殉道者之间,圣多米尼克,1424 年 - Christ in Majesty, predella, National Gallery, London.

荣耀中的基督,底座,国家美术馆,伦敦。

Florence, Basilica di San Marco

佛罗伦萨,圣马可大教堂

- Dormition of the Virgin, 1431[22]

圣母升天,1431 [22]

Florence, Santa Trinita 佛罗伦萨,圣三一

- Deposition of Christ, said by Vasari to have been "painted by a saint or an angel", National Museum of San Marco, Florence.

基督的下葬,瓦萨里称其为“由圣人或天使所绘”,佛罗伦萨圣马可国家博物馆。 - Coronation of the Virgin, c. 1432, Uffizi, Florence

处女的加冕,约 1432 年,乌菲兹美术馆,佛罗伦萨 - Coronation of the Virgin, c. 1434–1435, Louvre, Paris

圣母加冕,约 1434–1435 年,巴黎卢浮宫

Florence, Santa Maria degli Angeli

佛罗伦萨,圣玛丽亚·德尔·安杰利

- Last Judgement, Accademia, Florence

最后的审判,学院,佛罗伦萨

Florence, Santa Maria Novella

佛罗伦萨,圣玛丽亚诺维拉

- Coronation of the Virgin, altarpiece, Uffizi.

处女的加冕,祭坛画,乌菲兹美术馆。

San Marco, Florence, 1436–1445

圣马可,佛罗伦萨,1436–1445

- Altarpiece for chancel – Virgin with Saints Cosmas and Damian, attended by Saints Dominic, Peter, Francis, Mark, John Evangelist and Stephen. Cosmas and Damian were patrons of the Medici. The altarpiece was commissioned in 1438 by Cosimo de' Medici. It was removed and disassembled during the renovation of the convent church in the seventeenth century. Two of the nine predella panels remain at the convent; seven are in Washington, Munich, Dublin and Paris. Unexpectedly, in 2006 the last two missing panels, Dominican saints from the side panels, turned up in the estate of a modest collector in Oxfordshire, who had bought them in California in the 1960s.[23]

祭坛画 – 圣母与圣人科斯马斯和达米安,旁边是圣多明我、圣彼得、圣方济各、圣马可、圣约翰福音和圣斯蒂芬。科斯马斯和达米安是美第奇家族的保护神。该祭坛画于 1438 年由科西莫·美第奇委托制作。在十七世纪修缮修道院教堂时被拆除和分解。九个底座面板中有两个留在修道院;七个在华盛顿、慕尼黑、都柏林和巴黎。出人意料的是,在 2006 年,最后两个失踪的面板,即侧面板上的多明我圣人,出现在一位来自牛津郡的普通收藏家的遗产中,他在 1960 年代在加利福尼亚购买了它们。

十字架下的沉积,圣马尔科博物馆

圣母与圣人科斯马斯和达米安、圣马可和圣约翰、圣劳伦斯以及三位多米尼加人、圣多米尼克、圣托马斯·阿奎那和圣彼得·殉道者共同在宝座上;圣马可,佛罗伦萨

- Altarpiece ? – Madonna and Child with Twelve Angels (life sized); Uffizi.

祭坛画? – 圣母与圣婴及十二位天使(真人大小);乌菲兹美术馆。 - Altarpiece – The Annunciation

祭坛画 – 圣母领报 - San Marco Altarpiece 圣马可祭坛画

- Two versions of the Crucifixion with St Dominic; in the Cloister

圣多明哥的两幅十字架受难图;在回廊中 - Very large Crucifixion with Virgin and 20 Saints; in the Chapter House

非常大的十字架架构,带有圣母和 20 位圣人;在会议厅内 - The Annunciation; at the top of the Dormitory stairs. This is probably the most reproduced of all Fra Angelico's paintings.

报喜;在宿舍楼梯的顶部。这可能是弗拉·安杰利科所有画作中被复制最多的作品。 - Virgin Enthroned with Four Saints; in the Dormitory passage

圣母与四位圣人同座;在宿舍通道中

在《报喜》中,内部再现了其所在小房间的样子。

Each cell is decorated with a fresco which matches in size and shape of the single round-headed window beside it. The frescoes are apparently for contemplative purposes. They have a pale, serene, unearthly beauty. Many of Fra Angelico's finest and most reproduced works are among them. There are, particularly in the inner row of cells, some of the less inspiring quality and of the more repetitive subject, perhaps completed by assistants.[13] Many pictures include Dominican saints as witnesses of the scene each in one of the nine traditional prayer postures depicted in De Modo Orandi. The friar using the cell could place himself in the scene.

每个单元格都装饰着一幅壁画,壁画的大小和形状与旁边的单个圆顶窗户相匹配。这些壁画显然是为了沉思的目的。它们具有淡雅、宁静、超凡的美感。许多弗拉·安杰利科最优秀和最常被复制的作品都在其中。特别是在内侧的单元格中,有一些质量较低且主题更为重复的作品,可能是由助手完成的。 [13] 许多画作中包括多米尼加圣人作为场景的见证者,每位圣人都处于《祈祷方式》中描绘的九种传统祈祷姿势之一。使用该单元格的修士可以将自己置于场景中。

- The Adoration of the Magi

东方三博士的朝拜 - The Transfiguration 变形术

- Noli me tangere 不要碰我

- The Three Marys at the Tomb.

墓前的三位玛丽。 - The Road to Emmaus, with two Dominicans as the disciples

通往以马忤斯的路,两个多明戈人作为门徒 - The Mocking of Christ 基督的嘲弄

- There are many versions of the Crucifixion

有许多版本的十字架刑

Late works, 1445–1455 晚期作品,1445–1455

Three segments of the ceiling in the Cappella Nuova, with the assistance of Benozzo Gozzoli.

在卡佩拉诺瓦的三个天花板部分,得到了贝诺佐·戈佐利的协助。

- Christ in Glory 荣耀中的基督

- The Virgin Mary 圣母玛利亚

- The Apostles 使徒

The Chapel of Pope Nicholas V, at the Vatican, was probably painted with much assistance from Benozzo Gozzoli and Gentile da Fabriano. The entire surface of the wall and ceiling is sumptuously painted. There is much gold leaf for borders and decoration, and a great use of brilliant blue made from lapis lazuli.

教皇尼古拉五世的教堂位于梵蒂冈,可能在贝诺佐·戈佐利和詹蒂莱·达·法布里亚诺的帮助下完成。墙壁和天花板的整个表面都被华丽地绘制。边框和装饰使用了大量金箔,并大量使用了由青金石制成的明亮蓝色。

- The Life of St Stephen

圣斯蒂芬的生平 - The Life of St Lawrence

圣劳伦斯的生平 - The Four Evangelists. 四位福音书作者。

Discovery of lost works

失落作品的发现

Worldwide press coverage reported in November 2006 that two missing masterpieces by Fra Angelico had turned up, having hung in the spare room of the late Jean Preston, in her terrace house in Oxford, England. Her father had bought them for £100 each in the 1960s then bequeathed them to her when he died.[24] Preston, an expert medievalist, recognised them as being high-quality Florentine renaissance, but did not realize that they were works by Fra Angelico until they were identified in 2005 by Michael Liversidge of Bristol University.[25] There was almost no demand at all for medieval art during the 1960s and no dealers showed any interest, so Preston's father bought them almost as an afterthought along with some manuscripts. The paintings are two of eight side panels of a large altarpiece painted in 1439 for Fra Angelico's monastery at San Marco, which was later split up by Napoleon's army. While the centre section is still at the monastery, the other six small panels are in German and US museums. These two panels were presumed lost forever. The Italian Government had hoped to purchase them but they were outbid at auction on 20 April 2007 by a private collector for £1.7M.[24] Both panels are now restored and exhibited in the San Marco Museum in Florence.

2006 年 11 月,全球媒体报道两幅失踪的弗拉·安杰利科杰作在已故的简·普雷斯顿的牛津露台房屋的备用房间中被发现。她的父亲在 1960 年代以每幅 100 英镑的价格购买了它们,并在去世时将其遗赠给她。 [24] 普雷斯顿是一位中世纪艺术专家,认出它们是高质量的佛罗伦萨文艺复兴作品,但直到 2005 年布里斯托大学的迈克尔·利弗赛奇确认它们是弗拉·安杰利科的作品时,她才意识到这一点。 [25] 在 1960 年代,几乎没有人对中世纪艺术感兴趣,任何经销商都没有表现出兴趣,因此普雷斯顿的父亲几乎是随意购买了它们以及一些手稿。这两幅画是 1439 年为弗拉·安杰利科在圣马可修道院创作的大型祭坛画的八个侧面板中的两幅,该祭坛画后来被拿破仑的军队拆分。虽然中间部分仍在修道院,但其他六个小面板则在德国和美国的博物馆中。这两幅面板被认为永远失落。意大利政府曾希望购买它们,但在 2007 年 4 月 20 日的拍卖中被一位私人收藏家以 170 万英镑的价格超出出价。 [24] 两个面板现在已修复并在佛罗伦萨的圣马可博物馆展出。

See also 另见

- List of Italian painters

意大利画家名单 - List of famous Italians

著名意大利人名单 - Early Renaissance painting

早期文艺复兴绘画 - Poor Man's Bible 穷人的圣经

- Fray Angelico Chavez – Franciscan friar, historian and artist who was named after Fra Angelico due to his interest in painting

弗雷·安赫利科·查韦斯 – 方济各会修士、历史学家和艺术家,由于对绘画的兴趣而以弗拉·安赫利科命名 - Western painting 西方绘画

Footnotes 脚注

- "Metropolitan Museum of Art".

“大都会艺术博物馆”。 - Giorgio Vasari, Lives of the Artists. Penguin Classics, 1965.

乔尔乔·瓦萨里,《艺术家生平》。企鹅经典,1965 年。 - Norwich, John Julius (1990). Oxford Illustrated Encyclopedia Of The Arts. USA: Oxford University Press. pp. 16. ISBN 978-0-19-869137-2.

诺里奇,约翰·朱利叶斯(1990)。牛津插图艺术百科全书。美国:牛津大学出版社。第 16 页。ISBN 978-0-19-869137-2。 - Andrea del Sarto, Raphael and Michelangelo were all called "Beato" by their contemporaries because their skills were seen as a special gift from God

安德烈亚·德尔·萨尔托、拉斐尔和米开朗基罗都被他们的同时代人称为“贝阿托”,因为他们的技能被视为上帝的特殊恩赐 - Bunson, Matthew; Bunson, Margaret (1999). John Paul II's Book of Saints. Our Sunday Visitor. p. 156. ISBN 0-87973-934-7.

班森,马修;班森,玛格丽特(1999)。约翰·保罗二世的圣人书。我们的主日访客。第 156 页。ISBN 0-87973-934-7。 - Rossetti 1911, p. 6. 罗塞蒂 1911,第 6 页。

- Martyrologium Romanum, ex decreto sacrosancti oecumenici Concilii Vaticani II instauratum auctoritate Ioannis Pauli Pp. II promulgatum, editio [typica] altera, Typis Vaticanis, A.D. MMIV (2004), p. 155 ISBN 88-209-7210-7

罗马殉道志,依据神圣的第二届梵蒂冈大公会议的法令,由教皇约翰·保罗二世发布,第二版,梵蒂冈印刷,公元 2004 年,页码 155,ISBN 88-209-7210-7 - "Comune di Vicchio (Firenze), La terra natale di Giotto e del Beato Angelico". zoomedia. Retrieved 2007-09-28.

"维基奥市(佛罗伦萨),乔托和贝阿托·安杰利科的故乡"。zoomedia。检索于 2007-09-28。 - Werner Cohn, Il Beato Angelico e Battista di Biagio Sanguigni. Revista d'Arte, V, (1955): 207–221.

维尔纳·科恩,《祝福的安吉利科与比亚乔·桑圭尼的巴蒂斯塔》。艺术杂志,第五卷,(1955 年):207–221。 - Stefano Orlandi, Beato Angelico; Monographia Storica della Vita e delle Opere con Un'Appendice di Nuovi Documenti Inediti. Florence: Leo S. Olschki Editore, 1964.

斯特法诺·奥兰迪,《贝阿托·安杰利科;关于生活和作品的历史专著,附录新未发表文件》。佛罗伦萨:莱奥·S·奥尔斯基出版社,1964 年。 - Rossetti 1911, pp. 6–7.

- "Gherardo Starnina". Artists. Getty Center. Archived from the original on 2007-09-26. Retrieved 2007-09-28.Getty Education[]

“Gherardo Starnina”。艺术家。盖蒂中心。于 2007 年 9 月 26 日存档。于 2007 年 9 月 28 日检索。盖蒂教育[] - Frederick Hartt, A History of Italian Renaissance Art, (1970) Thames & Hudson, ISBN 0-500-23136-2

弗雷德里克·哈特,《意大利文艺复兴艺术史》,(1970)泰晤士河与哈德逊出版社,ISBN 0-500-23136-2 - "Strozzi, Zanobi". The National Gallery, London. Archived from the original on 2007-10-14. Retrieved 2007-09-28.

“斯特罗齐,扎诺比”。国家美术馆,伦敦。原文存档于 2007 年 10 月 14 日。检索于 2007 年 9 月 28 日。 - Rossetti, William Michael (as attributed) (18 March 2016). "Fra Angelico". orderofpreachersindependent.org. Retrieved 1 May 2016.

罗塞蒂,威廉·迈克尔(归因) (2016 年 3 月 18 日)。 "弗拉·安杰利科"。 orderofpreachersindependent.org。检索于 2016 年 5 月 1 日。 - The tomb has been given greater visibility since the beatification.

自从封圣以来,这座墓葬的知名度提高了。 - Rossetti 1911, p. 7. 罗塞蒂 1911,第 7 页。

- Michael Baxandall, Painting and Experience in Fifteenth Century Italy,(1974) Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-881329-5

迈克尔·巴克桑德,《十五世纪意大利的绘画与体验》,(1974)牛津大学出版社,ISBN 0-19-881329-5 - Paolo Morachiello, Fra Angelico: The San Marco Frescoes. Thames and Hudson, 1990. ISBN 0-500-23729-8

保罗·莫拉基耶洛,弗拉·安杰利科:《圣马可壁画》。泰晤士与哈德逊,1990 年。ISBN 0-500-23729-8 - The Crucifixion in the online databank of the MET.

大都会博物馆在线数据库中的《十字架上的耶稣》。 - Ross Finocchio in an essay on Fra Angelico at The Met's Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History in 2006.

罗斯·菲诺基奥在 2006 年于大都会艺术博物馆的海尔布伦艺术历史时间线上的一篇关于弗拉·安杰利科的文章。 - "Dormition of the Virgin". on WikiArt.org

“圣母升天”。在 WikiArt.org 上 - "San Marco Altarpiece". Web Gallery of Art. Retrieved 2014-05-29.

“圣马可祭坛画”。艺术网络画廊。检索于 2014-05-29。 - Morris, Steven (20 April 2007). "Lost altar masterpieces found in spare bedroom fetch £1.7m". The Guardian. Retrieved 2007-09-28.

莫里斯,史蒂文(2007 年 4 月 20 日)。“在备用卧室发现的失落祭坛杰作售价 170 万英镑”。《卫报》。检索于 2007 年 9 月 28 日。 - Morris, Steven (14 November 2006). "A £1m art find behind the spare room door". The Guardian. Retrieved 2007-09-28.

莫里斯,史蒂文(2006 年 11 月 14 日)。“在备用房间门后发现的 100 万英镑艺术品”。《卫报》。检索于 2007 年 9 月 28 日。

References 参考文献

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Rossetti, William Michael (1911). "Angelico, Fra". In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 2 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 6–8. Rossetti's article includes an assessment of the body of work, from the pre-Raphaelite viewpoint.

本文包含来自现已进入公有领域的出版物的文本:Rossetti, William Michael (1911)。“Angelico, Fra”。在 Chisholm, Hugh(编)。大英百科全书。第 2 卷(第 11 版)。剑桥大学出版社。第 6-8 页。Rossetti 的文章包括从前拉斐尔派的观点对作品的评估。

本文包含来自现已进入公有领域的出版物的文本:Rossetti, William Michael (1911)。“Angelico, Fra”。在 Chisholm, Hugh(编)。大英百科全书。第 2 卷(第 11 版)。剑桥大学出版社。第 6-8 页。Rossetti 的文章包括从前拉斐尔派的观点对作品的评估。 - Hood, William. Fra Angelico at San Marco. Yale University Press, 1993. ISBN 978-0-300-05734-8

胡德,威廉。《圣马可的弗拉·安杰利科》。耶鲁大学出版社,1993 年。ISBN 978-0-300-05734-8 - Morachiello, Paolo. Fra Angelico: The San Marco Frescoes. Thames and Hudson, 1990. ISBN 0-500-23729-8

莫拉基耶洛,保罗。《圣马可的弗雷斯科》。泰晤士河与哈德逊,1990 年。ISBN 0-500-23729-8 - Frederick Hartt. A History of Italian Renaissance Art, Thames & Hudson, 1970. ISBN 0-500-23136-2

弗雷德里克·哈特。意大利文艺复兴艺术史,泰晤士河与哈德逊出版社,1970 年。ISBN 0-500-23136-2 - Giorgio Vasari. Lives of the Artists. first published 1568. Penguin Classics, 1965.

乔尔乔·瓦萨里。《艺术家生平》。首次出版于 1568 年。企鹅经典,1965 年。 - Donald Attwater. The Penguin Dictionary of Saints. Penguin Reference Books, 1965.

唐纳德·阿特沃特。《企鹅圣人词典》。企鹅参考书籍,1965 年。 - Luciano Berti. Florence, the city and its Art. Bercocci, 1979.

卢西亚诺·贝尔蒂。《佛罗伦萨,城市及其艺术》。贝尔科奇,1979 年。 - Werner Cohn. Il Beato Angelico e Battista di Biagio Sanguigni. Revista d'Arte, V, (1955): 207–221.

维尔纳·科恩。《圣天使与比亚乔·桑圭尼的圣约翰》。艺术杂志,第五卷,(1955):207–221。 - Stefano Orlandi. Beato Angelico; Monographia Storica della Vita e delle Opere con Un'Appendice di Nuovi Documenti Inediti. Florence: Leo S. Olschki Editore, 1964.

斯特法诺·奥兰迪。《贝阿托·安杰利科;关于生活和作品的历史专著,附有新发现的未发表文件》。佛罗伦萨:莱奥·S·奥尔斯基出版社,1964 年。

Further reading 进一步阅读

- Nathaniel Silver (ed.), Fra Angelico: Heaven of Earth, Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston 2018

纳撒尼尔·西尔弗(编),《弗拉·安杰利科:人间的天堂》,伊莎贝拉·斯图尔特·加德纳博物馆,波士顿 2018 - Gerardo de Simone, Il Beato Angelico a Roma. Rinascita delle arti e Umanesimo cristiano nell'Urbe di Niccolò V e Leon Battista Alberti, Fondazione Carlo Marchi, Studi, vol. 34, Olschki, Firenze 2017

赫拉尔多·德·西蒙,罗马的圣天使。尼科洛·五世和莱昂·巴蒂斯塔·阿尔贝蒂时代的艺术复兴与基督教人文主义,卡洛·马尔基基金会,研究,第 34 卷,奥尔斯基,佛罗伦萨 2017 - Cyril Gerbron, Fra Angelico. Liturgie et mémoire (= Études Renaissantes, 18), Brepols Publishers, Turnhout 2016. ISBN 978-2-503-56769-3;

- Gerardo de Simone, "La bottega di un frate pittore: il Beato Angelico tra Fiesole, Firenze e Roma", in Revista Diálogos Mediterrânicos, n. 8, Curitiba (Brasil) 2015, ISSN 2237-6585, pp. 48–85 – http://www.dialogosmediterranicos.com.br/index.php/RevistaDM

Gerardo de Simone, "一位画家修士的工作坊:贝阿图斯·安杰利科在菲耶索莱、佛罗伦萨和罗马之间", 载于《地中海对话杂志》,第 8 期,库里提巴(巴西)2015 年,ISSN 2237-6585,第 48–85 页 – http://www.dialogosmediterranicos.com.br/index.php/RevistaDM - Gerardo de Simone, "Fra Angelico: perspectives de recherche, passées et futures", in Perspective, la revue de l'INHA. Actualités de la recherche en histoire de l'art, 1/2013, pp. 25–42

Gerardo de Simone, "Fra Angelico: 研究视角,过去与未来", 载于《Perspective》,INHA 杂志。艺术史研究动态,1/2013,页 25–42 - Gerardo de Simone, "Velut alter Iottus. Il Beato Angelico e i suoi 'profeti trecenteschi'", in 1492. Rivista della Fondazione Piero della Francesca, 2, 2009 (2010), pp. 41–66

- Gerardo de Simone, "L'Angelico di Pisa. Ricerche e ipotesi intorno al Redentore benedicente del Museo Nazionale di San Matteo", in Polittico, Edizioni Plus – Pisa University Press, 5, Pisa 2008, pp. 5–35

Gerardo de Simone, "比萨的天使。关于圣马太国家博物馆中祝福救主的研究与假设", 收录于《多联画》,Plus 出版社 – 比萨大学出版社,第 5 卷,比萨 2008 年,第 5–35 页 - Gerardo de Simone, "L'ultimo Angelico. Le "Meditationes" del cardinal Torquemada e il ciclo perduto nel chiostro di S. Maria sopra Minerva", in Ricerche di Storia dell'Arte, Carocci Editore, Roma 2002, pp. 41–87

Gerardo de Simone, "最后的天使。托尔奎马达红衣主教的《冥想》与圣玛丽亚上方明尔瓦修道院失落的循环", 收录于《艺术史研究》,Carocci 出版社,罗马 2002 年,第 41–87 页 - Creighton Gilbert, How Fra Angelico and Signorelli Saw the End of the World, Penn State Press, 2002 ISBN 0-271-02140-3

克雷顿·吉尔伯特,《弗朗切斯科·安杰利科和西尼奥雷利如何看待世界的终结》,宾州州立大学出版社,2002 年 ISBN 0-271-02140-3 - John T. Spike, Angelico, New York 1997.

约翰·T·斯派克,《安杰利科》,纽约 1997。 - Georges Didi-Huberman, Fra Angelico: Dissemblance and Figuration. University of Chicago Press, Chicago 1995. ISBN 0-226-14813-0 Discussion of how Fra Angelico challenged Renaissance naturalism and developed a technique to portray "unfigurable" theological ideas.

乔治·迪迪-于贝尔曼,《佛朗西斯科·安杰利科:隐喻与具象》。芝加哥大学出版社,芝加哥 1995 年。ISBN 0-226-14813-0 讨论了佛朗西斯科·安杰利科如何挑战文艺复兴自然主义,并发展出一种表现“不可具象化”神学思想的技巧。 - J. B. Supino, Fra Angelico, Alinari Brothers, Florence, undated, from Project Gutenberg

J. B. Supino, 弗拉·安杰利科, 阿利纳里兄弟, 佛罗伦萨, 未注明日期, 来自古腾堡计划

External links 外部链接

- Fra Angelico – Painter of the Early Renaissance

弗朗切斯科·安杰利科 – 早期文艺复兴的画家[usurped] - Fra Angelico in the "History of Art"

弗朗切斯科·安杰利科在《艺术史》中 Archived 归档 2012-02-25 at the

2012 年 2 月 25 日在Wayback Machine 时光机 - Ross Finocchio, Robert Lehman Collection, The Metropolitan Museum of Art

罗斯·菲诺基奥,罗伯特·莱曼收藏,大都会艺术博物馆 - Fra Angelico Exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, (October 26, 2005 – January 29, 2006).

大都会艺术博物馆的弗拉·安杰利科展览(2005 年 10 月 26 日–2006 年 1 月 29 日)。 - "Soul Eyes" Archived 2008-12-03 at the Wayback Machine Review of the Fra Angelico show at the Met, by Arthur C. Danto in The Nation, (January 19, 2006).

《灵魂之眼》 归档于 2008 年 12 月 03 日的时光机 由亚瑟·C·丹托在《国家》上对大都会博物馆的弗拉·安杰利科展览的评论(2006 年 1 月 19 日)。 - Fra Angelico, Catherine Mary Phillimore, (Sampson Low, Marston & Co., 1892)

弗拉·安杰利科,凯瑟琳·玛丽·菲利莫尔,(萨姆森·洛、马斯顿与公司,1892) - Frescoes and paintings gallery

壁画和绘画画廊 Archived 归档 2016-03-04 at the

2016-03-04 在Wayback Machine 时光机 - Italian Paintings: Florentine School, a collection catalog containing information about the artist and his works (see pages: 77–82).

意大利画作:佛罗伦萨学派,一本包含艺术家及其作品信息的目录(见页码:77–82)。

Wikiwand in your browser!

在您的浏览器中使用 Wikiwand!

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

无缝的维基百科浏览。增强版。

Every time you click a link to Wikipedia, Wiktionary or Wikiquote in your browser's search results, it will show the modern Wikiwand interface.

每次您在浏览器的搜索结果中点击指向 Wikipedia、Wiktionary 或 Wikiquote 的链接时,它将显示现代的 Wikiwand 界面。

Wikiwand extension is a five stars, simple, with minimum permission required to keep your browsing private, safe and transparent.

Wikiwand 扩展是一个五颗星的简单工具,所需权限最少,可以保持您的浏览私密、安全和透明。