Top China Economist Asks State to Curb Sway in Funding Startups

- Yao says government funds not well suited for venture capital

- Urgency growing in China to support confidence, private sector

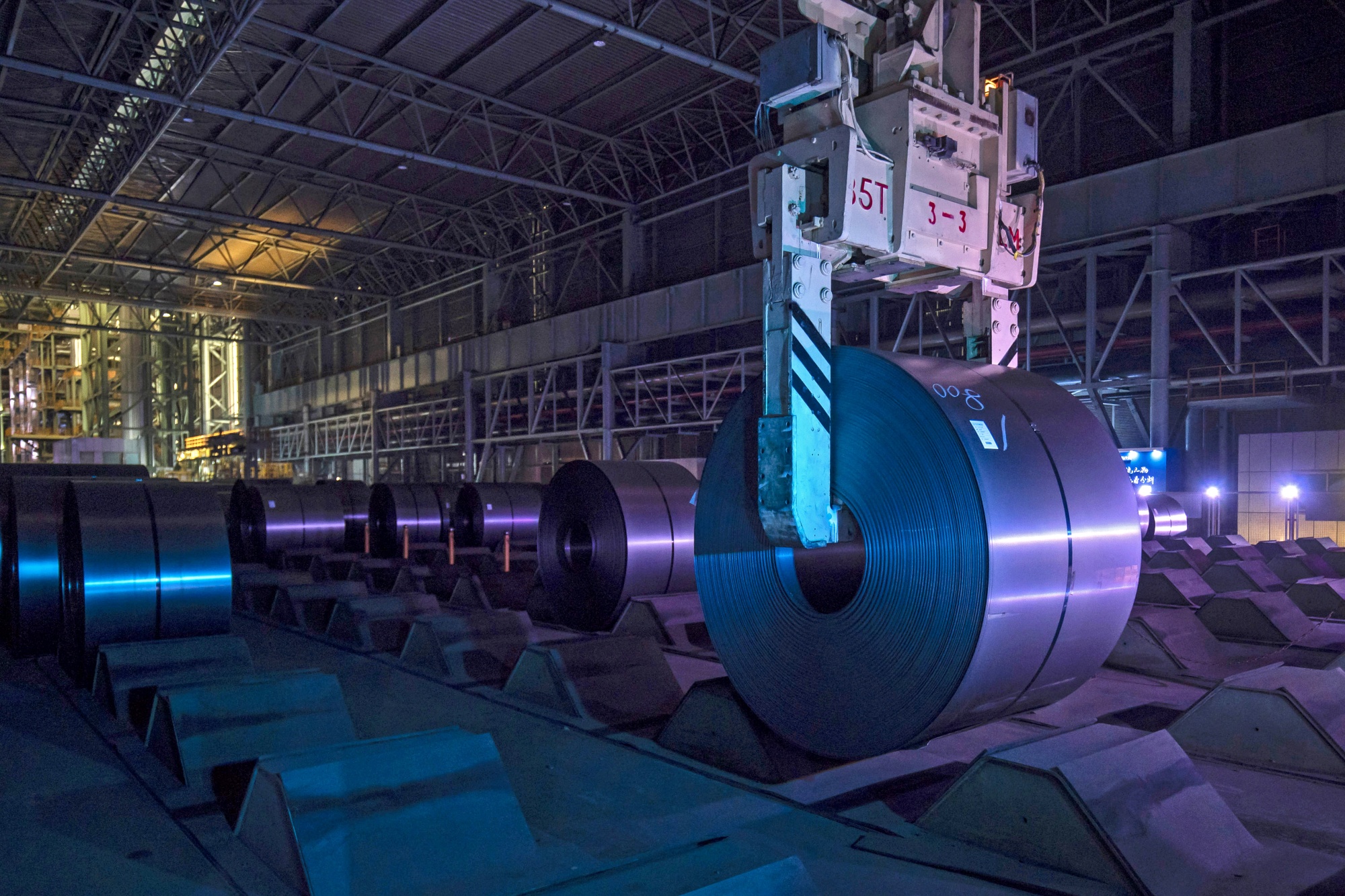

A prominent Chinese economist has urged state funds to retreat from venture capital and allow the private sector to play a bigger role in a critical industry that’s enduring its weakest investment in years.

“The government portion of the current venture capital industry is too high,” said Peking University professor Yao Yang during an interview with Bloomberg News. The state prioritizes safety, he said, which could be a drawback in an industry often defined by a higher acceptance of risk in exchange for future returns.

The appeal points to a recognition by some in China’s establishment that the state-heavy approach is failing in its mission of funding cutting-edge technologies. By some estimates, the Chinese government invests six times more than privately-owned firms in private equity and venture capital — a key source of financing for startups.

Trained in the US, Yao has participated in seminars with top officials including President Xi Jinping and former Vice Premier Liu He, and his writings have won recognition from senior leadership. He’s described himself as a “left-wing economist,” advocating greater protection of worker rights — especially in tech — and arguing that the ruling Communist Party is in need of new theories founded on Confucianism.

In the interview, Yao commented on recent debates that show China is reconsidering the role of the state and the private sector at a time when rivalry with the US intensifies and Xi is on a quest for breakthroughs in tech and innovation.

Beijing has shifted to a more pro-business rhetoric as it seeks to bolster a post-Covid recovery. Last year, China’s Communist Party and government vowed to improve conditions for private businesses in a rare joint statement that set out 31 measures and even established a new agency to promote private sector growth.

But the initiatives largely fell flat. Venture capital financing in China shrank by more than 7% in 2023 and reached its lowest in four years, according to data collated by Preqin, as investors cooled on startups and grew concerned over regulations and the state of the economy.

Since government officials are held accountable for financial performance, they often require companies they work with to enter into contracts that protect the investor in case of a loss.

That’s at odds with how innovative startups operate, said Yao, adding that decision makers need a better understanding of the relationship between finance and innovation.

Tighter Grip

Mobilizing private capital might prove a challenge.

Xi has over the past few years tightened control of China’s private sector, cracking down on tech moguls and the tutoring industry. More recently, he’s lashed out at financial elites, vowing to rein in the “disorderly expansion of capital.”

The fate of once high-flying executives such as Alibaba Group Holding Ltd. founder Jack Ma has deflated the can-do spirit that helped fuel China’s rapid growth over past decades. Many of the country’s rich have left — by one estimate, China is on track to lose 15,200 millionaires this year, the most in the world.

Even so, recent party documents capture the changing sentiment around ownership and rewards for investment, showing the Chinese government is trying to restore confidence among entrepreneurs.

Still a Mainstay?

Omitting the description of public ownership as “the mainstay” in a document released after the party’s flagship policy meeting in July means there’s place for both public and private firms in China’s economy in the long term, Yao said.

Read more: Ex-China Editor Hu Banned on Social Media After Post on Economy

The party resolutions after the high-level gathering known as the Third Plenum also altered the language surrounding income distribution to give equal weight to all factors of production — including labor, capital and land — and emphasized they’ll be rewarded by the market, Yao said.

That’s also a break from the long-standing theory on how wealth should be distributed and the role of capital in China’s socialist economy.

The issues are politically sensitive in China since they represent central planks of the ruling Communist Party’s official ideology.

No updates of official theories are formal until they are written into the constitutions of the country and the party. The evolving narratives are unlikely to immediately lead to any major changes in policy but could herald long-term developments in thinking that underpin government decisions.

Such shifts in language should be reason for optimism in the private sector, according to Yao, who said there were fears among businesspeople and the country’s middle class that public ownership will further expand as China’s socialism moves from a “primary stage” toward a more advanced level.

“The Plenum gives them reassurance that Chinese socialism will stabilize with mixed ownership, and they will be equally protected or punished when violating laws,” he said.

— With assistance from Lucille Liu and Jing Li