摘要

我们对阿尔茨海默病(AD)的病理生理学的理解仍然不完整。在这里,我们使用定量质谱和共表达网络分析进行迄今为止最大的蛋白质组学研究AD。与糖代谢相关的蛋白质网络模块成为与AD病理学和认知障碍最显著相关的模块之一。该模块富含AD遗传风险因素以及与抗炎状态相关的小胶质细胞和星形胶质细胞蛋白标志物,表明其所代表的生物学功能在AD中起保护作用。在疾病的早期阶段,来自该模块的蛋白质在脑脊液中升高。在这项通过定量蛋白质组学对>2000脑和近400份脑脊液样本的研究中,我们鉴定了AD脑中可能作为该疾病的治疗靶点和流体生物标志物的蛋白质和生物学过程。

介绍

阿尔茨海默病(AD)是全球范围内的主要死亡原因,随着全球预期寿命的增加,患病率增加1。尽管AD目前是基于新皮质内的淀粉样蛋白-β斑块和tau神经元缠结沉积来定义的2,但是表征该疾病的脑中的生化和细胞变化超出淀粉样蛋白-β和tau沉积仍然不完全清楚。蛋白质共表达分析是了解人体组织中生物网络、途径和细胞类型变化的有力工具3,4。共表达蛋白质的群落可以与疾病过程相关联,并且这些共表达模块内最强相关的蛋白质或“枢纽”富含疾病发病机制的关键驱动因素5-10。 因此,靶向与疾病生物学最相关的蛋白质共表达模块内的枢纽是药物和生物标志物开发的有前途的方法11-14。在这里,我们描述了一个多中心联盟的研究,在加速医学合作伙伴关系的AD,以分析超过2000人脑组织的定量质谱为基础的蛋白质组学。我们从多个研究中心获得的453个大脑中生成了一个共识AD脑蛋白共表达网络,控制了批次和其他协变量。我们使用不同的基于质谱的蛋白质定量技术在一个单独的基于社区的队列中验证了这个蛋白质网络,并表明该网络在AD受影响的不同大脑区域中得到了保留。通过分析一个单独的正常老化大脑队列,我们能够估计老化对观察到的AD大脑蛋白共表达网络的影响。 我们还通过在其他6种神经退行性疾病(包括不同的脑病理)中询问这些变化来分析AD蛋白网络变化的疾病特异性,并通过靶向蛋白测量来验证观察到的变化。改变最强烈的AD蛋白共表达模块之一,我们称之为“星形胶质细胞/小胶质细胞代谢”模块,富含与小胶质细胞、星形胶质细胞和糖代谢相关的蛋白质,并且富含与AD遗传风险相关的蛋白质产物。该模块中的小胶质细胞蛋白标记物偏向于抗炎性疾病相关状态,表明其反映了对AD病理学应答的保护或补偿功能。来自该模块的蛋白质在AD患者的脑脊液中增加,包括在疾病的无症状阶段。 我们的研究结果强调了炎症、糖代谢、线粒体功能、突触功能、RNA相关蛋白和胶质细胞在AD发病机制中的重要性,并为未来关于AD脑和生物流体生物标志物的蛋白质组学和多组学研究提供了一个强有力的框架。

结果

共有AD蛋白共表达网络的构建与验证

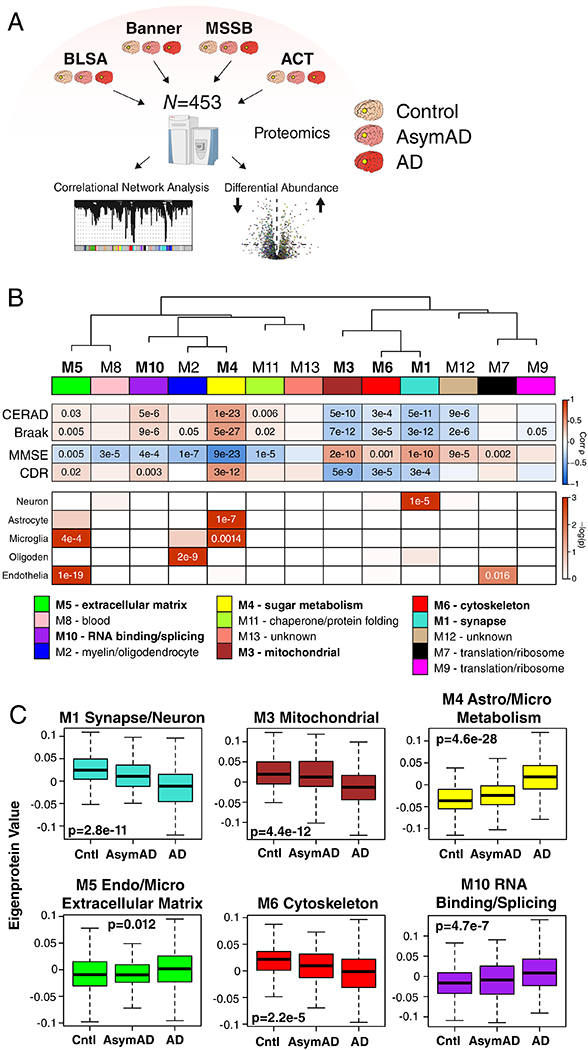

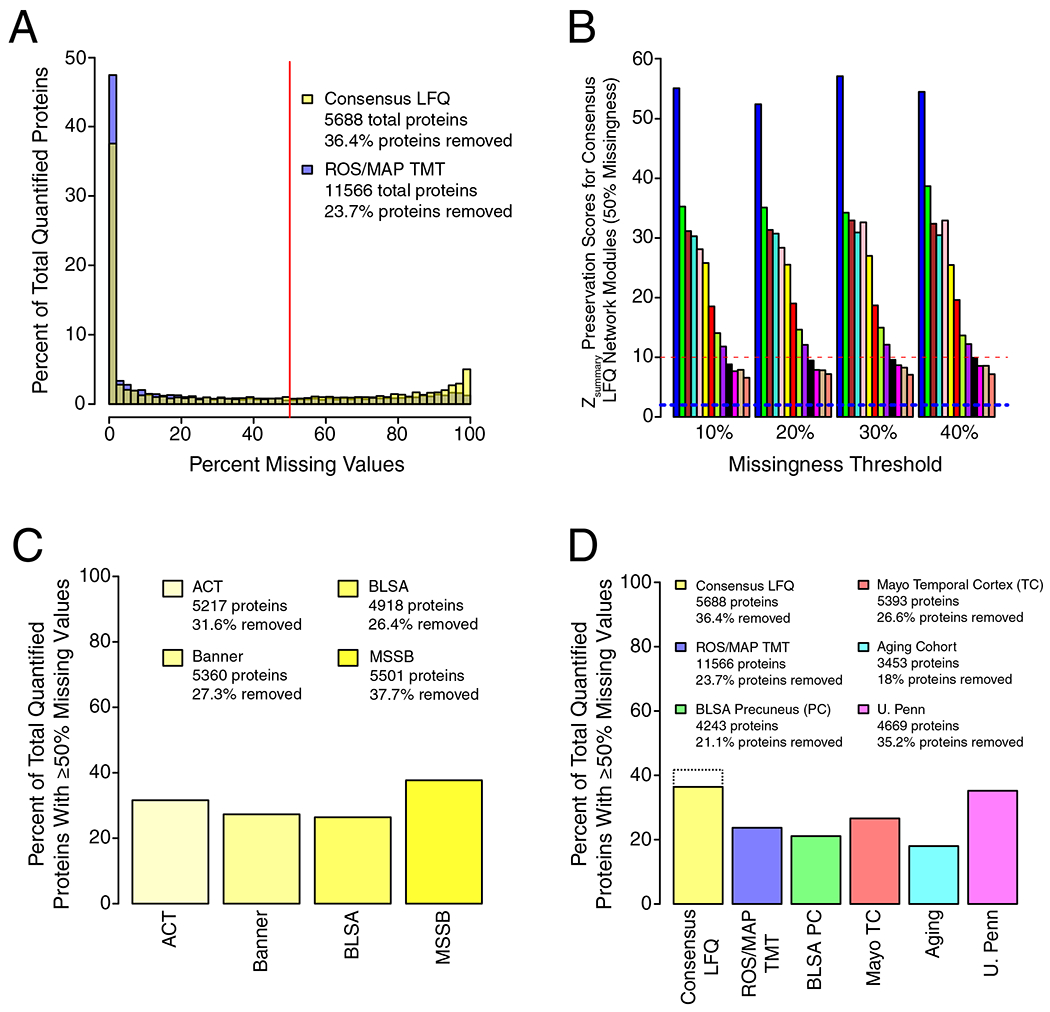

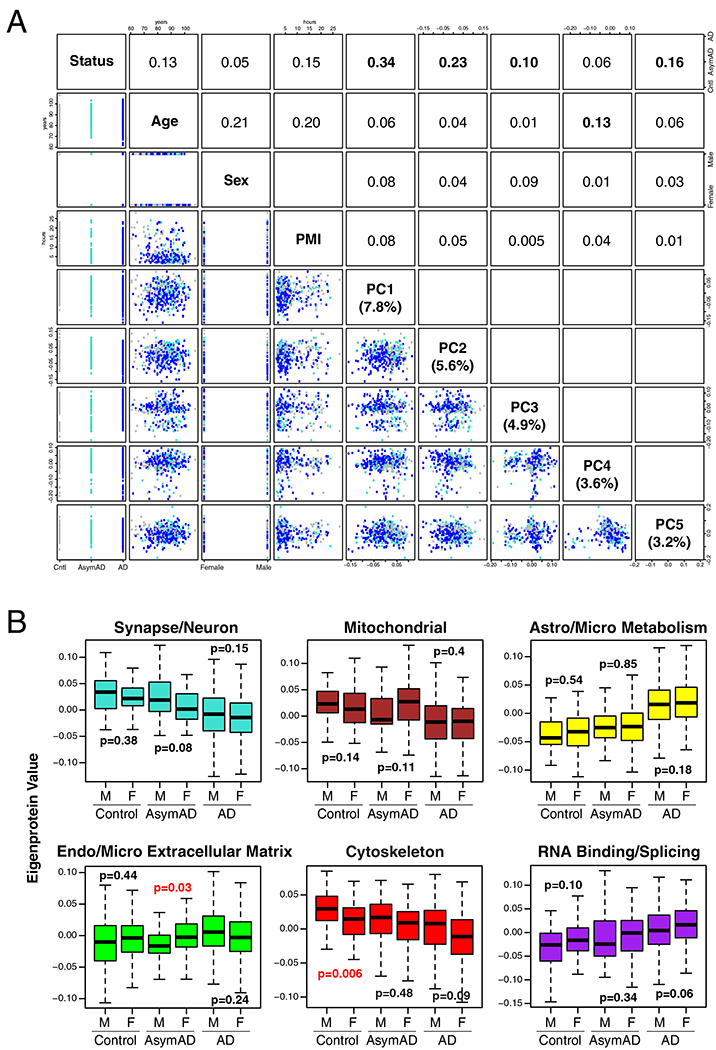

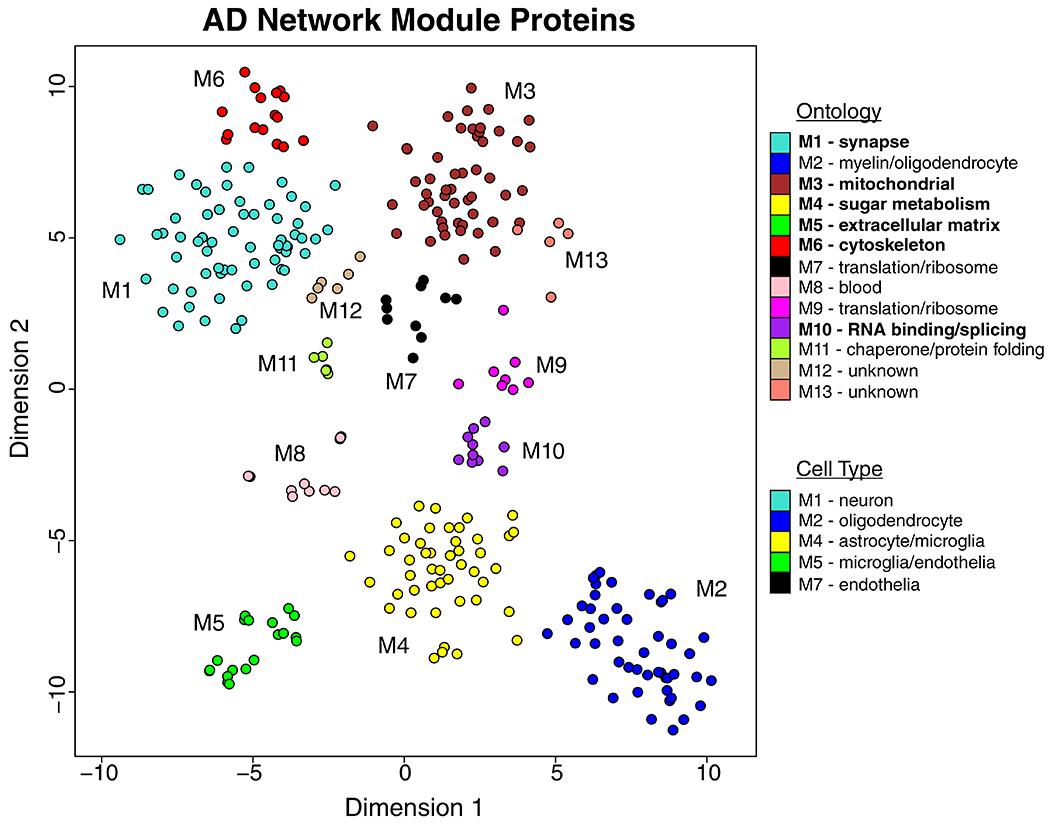

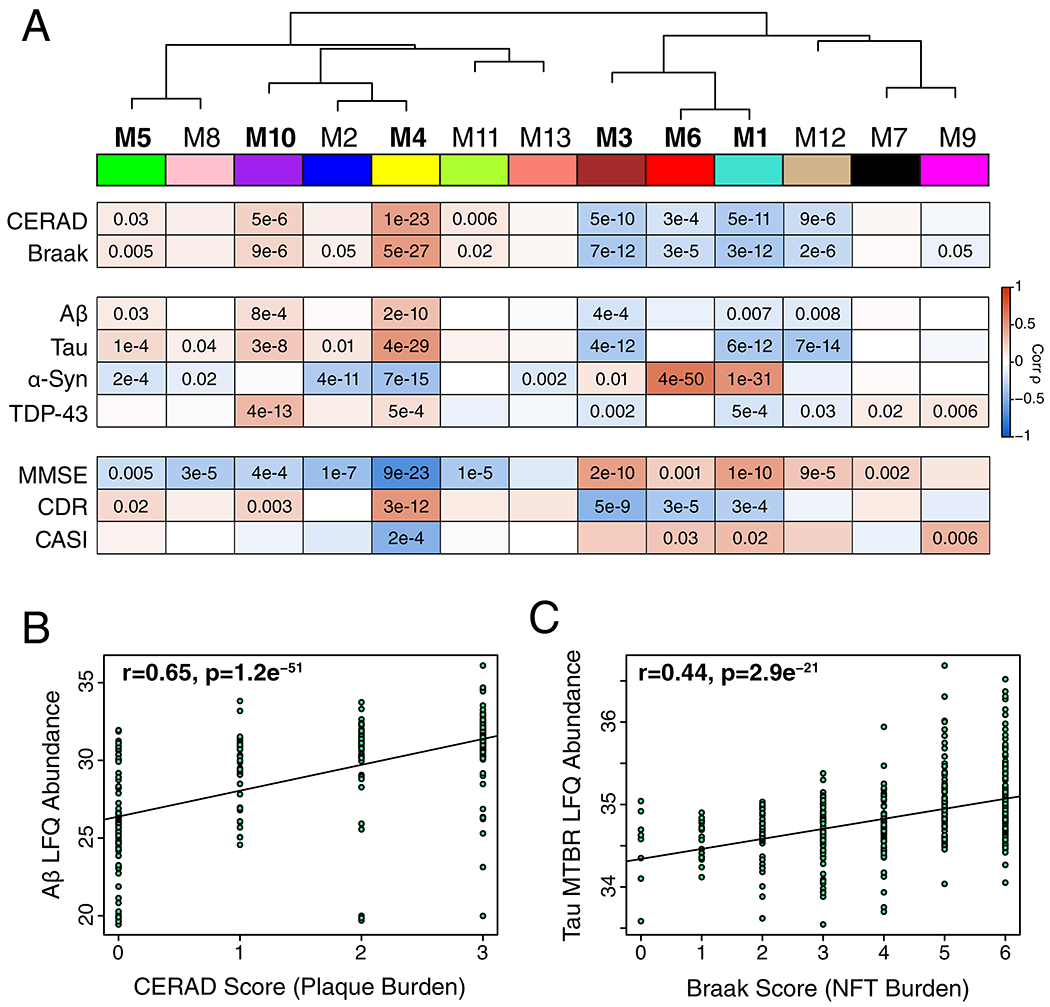

We analyzed dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC) tissue in 44 cases from the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging (BLSA), 178 cases from the Banner Sun Health Research Institute (Banner), 166 cases from the Mount Sinai School of Medicine Brain Bank (MSSB), and 65 cases from the Adult Changes in Thought Study (ACT), for a total of 453 control, asymptomatic AD (AsymAD), and AD brains (Figure 1A, Supplementary Table 1). AsymAD was defined as postmortem pathology consistent with an AD diagnosis but without dementia, based on the NIA research framework for AD2. Tissues were analyzed by mass spectrometry-based proteomics using label-free quantitation (LFQ), and the resulting mass spectrometry data were processed using a common pipeline to arrive at 5688 total quantified proteins. We included proteins with fewer than 50% missing values in the subsequent analyses, as it was determined that this threshold was robust to potential spurious correlations given the power of the study (Extended Data Figure 1). We also removed by regression the effects of age, sex, and post-mortem interval on the protein quantitative data, even though these covariates did not strongly influence the data (Extended Data Figure 2). The final adjusted 3334 proteins were used to generate a protein co-expression network using the weighted correlation network analysis (WGCNA) algorithm. The resulting network consisted of 13 protein co-expression “modules,” or communities of proteins with similar expression patterns across the cases analyzed (Figure 1B, Supplementary Figures 1 and 2, Supplementary Table 2). The modules ranged in size from 254 proteins (M1) to 20 proteins (M13). These modules could also be identified independently of the WGCNA algorithm using t-distributed stochastic neighbor embedding (t-SNE) analysis (Extended Data Figure 3), demonstrating that the protein communities identified by the WGCNA algorithm were robust. Gene ontology (GO) analysis of the protein module members revealed a clear ontology for eleven out of the thirteen modules, encompassing a diverse mix of biological functions, processes, and components (Figure 1B, Supplementary Figure 3). To assess whether a given co-expression module was related to AD, we correlated the module eigenprotein—or first principle component of the module protein expression level—to the neuropathological hallmarks of AD: amyloid-β plaques and neurofibrillary tangles. We also correlated the module eigenproteins to cognitive function as assessed by the Mini-Mental Status Examination (MMSE), and functional status as assessed by the Clinical Dementia Rating Scale (CDR), at the last research evaluations prior to death to capture module-disease relationships that may be independent of amyloid-β plaque or tau tangle pathology (Figure 1B, Supplementary Figure 1). We observed six modules that were significantly correlated with all pathological, cognitive, and functional measures, and whose ontologies could be best characterized by a structural component or a biologic process: modules M1 synapse, M3 mitochondrial, M4 glucose and carbohydrate metabolism (subsequently referred to as sugar metabolism), M5 extracellular matrix, M6 cytoskeleton, and M10 RNA binding/splicing. The M4 sugar metabolism module showed the strongest AD trait correlations (cognition r=−0.67, p=8.5e−23; neurofibrillary tangle r=0.49, p=4.7e−27; amyloid-β plaque r=0.46, p=1.3e−23; functional status r=0.52, p=2.6e−12). Because AD neuropathology is not homogenous even within the same brain region, and because neuropathological measurements of AD pathology are semi-quantitative and subject to a certain degree of individual variability in assessment15, we also correlated module eigenproteins to mass spectrometry measurements of amyloid-β and the tau microtubule binding region, which comprises neurofibrillary tangles, within the DLPFC tissue used for proteomic analysis (Extended Data Figure 4). We observed strong concordance between neuropathological and molecular measurements of AD pathology. 重试 错误原因

图1.无症状和症状性阿尔茨海默病脑蛋白质网络分析

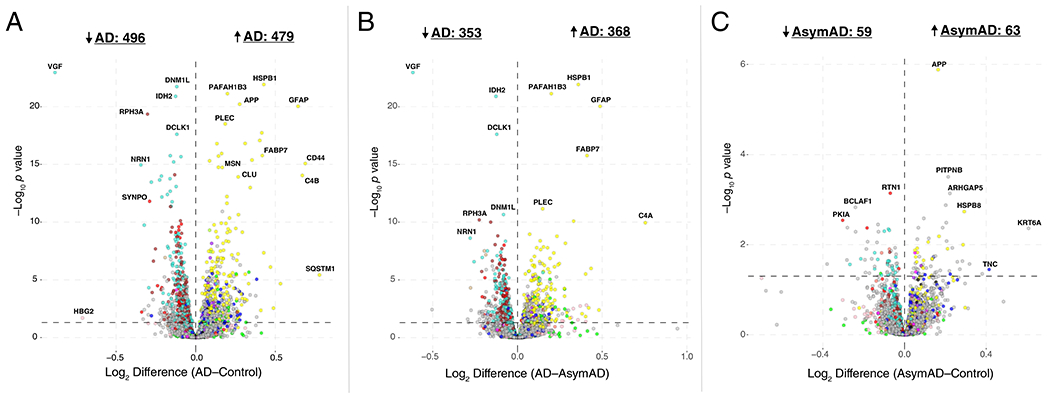

(A-C) Protein levels in brain tissue from control, asymptomatic Alzheimer’s disease (AsymAD), and Alzheimer’s disease (AD) patients (N=453) were measured by label-free mass spectrometry and analyzed by weighted correlation network analysis (WGCNA) and differential abundance (A). Brain tissue was analyzed from postmortem dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC, highlighted in yellow) in the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging (BLSA, n=11 control, n=13 AsymAD, n=20 AD, n=44 total), Banner Sun Health Research Institute Brain Bank (Banner, n=26 control, n=58 AsymAD, n=94 AD, n=178 total), Mount Sinai School of Medicine Brain Bank (MSSB, n=46 control, n=17 AsymAD, n=103 AD, n=166 total), and the Adult Changes in Thought Study (ACT, n=11 control, n=14 AsymAD, n=40 AD, n=65). (B) A protein correlation network consisting of 13 protein modules was generated from 3334 proteins measured across four separate cohorts. (Top) Module eigenproteins, which represent the first principle component of the protein expression within each module, were correlated with neuropathological hallmarks of Alzheimer’s disease (CERAD, Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer’s disease amyloid-β plaque score, higher scores represent greater plaque burden; Braak, tau neurofibrillary tangle staging score, higher scores represent greater extent of tangle burden), cognitive function (MMSE, mini-mental status examination score, higher scores represent better cognitive function), and overall functional status (CDR, clinical dementia rating score, higher scores represent worse functional status). CERAD and Braak measures were from all cohorts, while MMSE was from Banner and CDR was from MSSB. Strength of positive (red) or negative (blue) correlation is shown by two-color heatmap, with p values provided for all correlations with p < 0.05. Modules that showed a significant correlation with all four traits are highlighted in bold. (Middle) The cell type nature of each protein module was assessed by module protein overlap with known neuron, astrocyte, microglia, oligodendrocyte (oligoden), and endothelia cell markers. Significance of overlap is shown by one-color heatmap, with p values provided for overlaps with p < 0.05. (Bottom) Gene ontology (GO) analysis of the proteins within each module clearly identified, for most modules, the biological processes associated with the module. (C) Module eigenprotein level by case status for each protein module that had significant correlation to all four traits in (B). Case status is from all cohorts (control, n=91; AsymAD, n=98; AD, n=230 after network connectivity outlier removal). APOE genotype effects and other trait correlations for all modules are provided in Supplementary Figure 1. Module eigenprotein correlations were performed using biweight midcorrelation and corrected by the Benjamini-Hochberg method. Protein module cell type overlap was performed using one-sided Fisher’s exact test with Benjamini-Hochberg correction. Differences in eigenprotein values were assessed by Kruskal-Wallis one-way ANOVA. Boxplots represent the median, 25th, and 75th percentiles, and whiskers represent measurements to the 5th and 95th percentiles. Cntl, control; AsymAD, asymptomatic Alzheimer’s disease; AD, Alzheimer’s disease.

Because many protein co-expression changes in the brain can be driven by cell type changes16,17, we also assessed the cell type nature of each co-expression module by asking whether the module was enriched in particular cell type marker proteins (Figure 1B). We observed significant enrichment of neuronal proteins in the M1 synapse module and enrichment of oligodendrocyte markers in the M2 myelin module, as expected. We also observed enrichment of astrocyte and microglial proteins in the M4 sugar metabolism module, microglial and endothelial proteins in the M5 extracellular matrix module, and endothelial markers in the M7 translation/ribosome module. These findings suggest that the biological processes reflected by GO analysis for each module may be altered in AD within a particular cell type. To incorporate the cell type nature of each module into its description, we subsequently refer to those modules with strong cell type enrichment as the “M1 synapse/neuron” module, the “M2 myelin/oligodendrocyte” module, the “M4 astrocyte/microglial metabolism” module, and the “M5 endo/micro extracellular matrix” module.

To assess the relationship of the network modules to diagnostic classification, we measured the module eigenprotein values by case status (Figure 1C and Supplementary Figure 1). In general, most modules that were increased or decreased in AD compared to control also showed a trend, or were significantly changed, in the same direction in the AsymAD group, indicating that these modules reflect pathophysiologic processes that begin early—in the preclinical phase—of AD. The M1 synapse/neuron, M3 mitochondrial, and M4 astrocyte/microglial metabolism modules showed the strongest differences by case status. We also assessed the influence of APOE genotype on module eigenproteins, but did not find strong effects except for the APOE ε2 allele on the M2 myelin/oligodendrocyte module, which appeared to attenuate the observed changes in AD (Supplementary Figure 1).

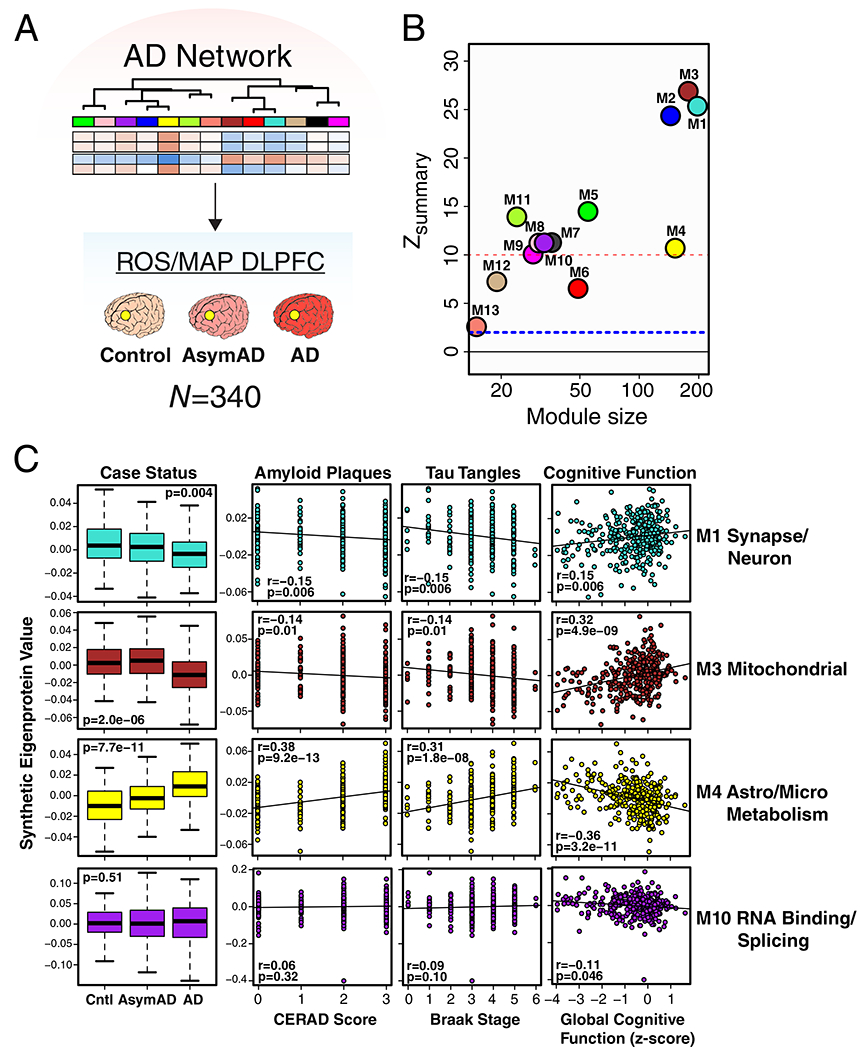

To validate the AD network, we analyzed 340 DLPFC brain tissues from a community-based aging cohort, the Religious Orders Study and Memory and Aging Project (ROS/MAP)18–20, with a different mass spectrometry-based protein quantification approach using isobaric multiplex tandem mass tags (TMT)21–23. A protein co-expression network was constructed from the ROS/MAP cases, and network module preservation statistics as well as synthetic module eigenproteins were used to assess conservation of the consensus AD LFQ-based network in the ROS/MAP TMT-based network (Extended Data 5B and C, Supplementary Figure 4). We found that all consensus LFQ modules were preserved in the ROS/MAP TMT-based network. Furthermore, targeted protein measurements in a cohort of 1016 ROS/MAP control, AsymAD, and AD brains by another mass spectrometry protein quantification approach—selected reaction monitoring (SRM)—showed that individual module proteins had the same direction of change as the AD LFQ-based network co-expression module of which they were a member (Supplementary Figures 5 and 6). In summary, we were able to construct a robust AD protein co-expression network from mass spectrometry-based proteomic analysis of greater than 450 human DLPFC brain tissues from multiple centers. We found that many of these modules correlated with AD neuropathology and cognitive function, reflected a number of different biological processes and cell types, and were altered in the preclinical stage of AD.

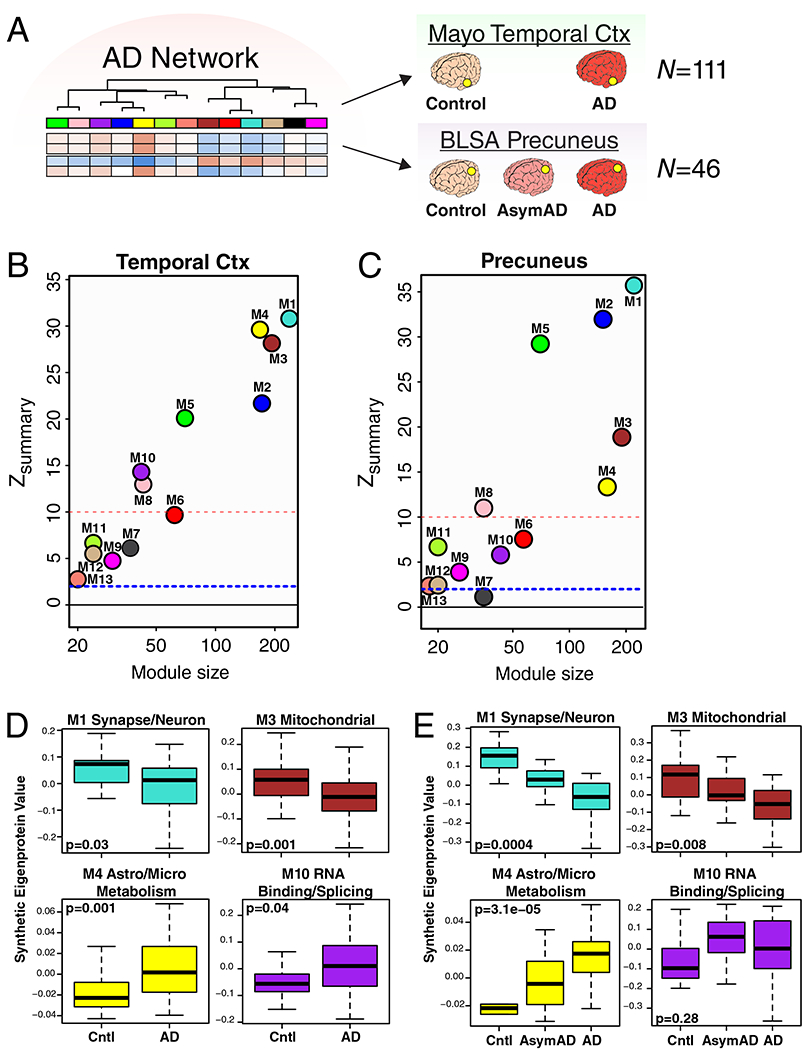

The AD Network Is Preserved in Other Brain Regions

The consensus AD network was generated from analysis of DLPFC tissue. To assess whether the network was similar in other brain regions commonly affected in AD, we analyzed control and AD brain tissue from temporal cortex in a separate set of 111 brains from the Mayo Clinic, and control, AsymAD, and AD brain tissue from precuneus in the same set of brains from the BLSA (Figure 2A) using LFQ-MS. Co-expression networks were built for each brain region, and network preservation statistics were used to assess module preservation from DLPFC in temporal cortex (Figure 2B) and precuneus (Figure 2C). We found that all consensus AD network modules derived from DLPFC were preserved in temporal cortex, and twelve out of the thirteen modules were preserved in precuneus. Analysis of synthetic module eigenprotein values by case status showed similar differences between and among case groups in temporal cortex (Figure 2D, Supplementary Figure 7) and precuneus (Figure 2E, Supplementary Figure 8) brain regions, with changes in AsymAD more pronounced in precuneus than in DLPFC. These findings suggest that the consensus AD network is generalized across brain regions that are commonly affected in AD.

Figure 2. AD Protein Network Is Preserved in Different Brain Regions.

(A-E) Preservation of AD protein network modules derived from analysis of DLPFC in other brain regions affected by AD. (A) Protein levels in temporal cortex from a total of 111 control and AD cases (control, n=28; AD, n=83) from the Mayo Brain Bank, and in precuneus from a total of 46 cases from the BLSA (control, n=12; AsymAD, n=14; AD, n=20) were measured by label-free mass spectrometry and used to assess conservation of the AD brain protein network derived from DLPFC. (B, C) AD brain protein network preservation in temporal cortex (B) and precuneus (C). Module preservation was calculated using a composite zsummary score as described by Langfelder et al.73 The dashed blue line indicates a zsummary score of 1.96, or FDR q value <0.05, above which module preservation was considered statistically significant. The dashed red line indicates a zsummary score of 10, or FDR q value ~ 1e−23, above which module preservation was considered highly statistically significant. (D, E) Case status preservation in temporal cortex and precuneus. A synthetic eigenprotein was created for each AD network module as described in Extended Data Figure 5 and measured by case status in temporal cortex (D) and precuneus (E). Asymptomatic AD was not assessed in the Mayo cohort, and is therefore not included in the temporal cortex analyses. Synthetic eigenprotein analyses for modules M1, M3, M4, and M10 are shown. Analyses for all modules, with additional trait correlations, are provided in Supplementary Figures 7 and 8. Differences in module synthetic eigenproteins by case status were assessed by two-sided Welch’s t test (D) or Kruskal-Wallis one-way ANOVA (E). Boxplots represent the median, 25th, and 75th percentiles, and whiskers represent measurements to the 5th and 95th percentiles. Cntl, control; AsymAD, asymptomatic Alzheimer’s disease; AD, Alzheimer’s disease.

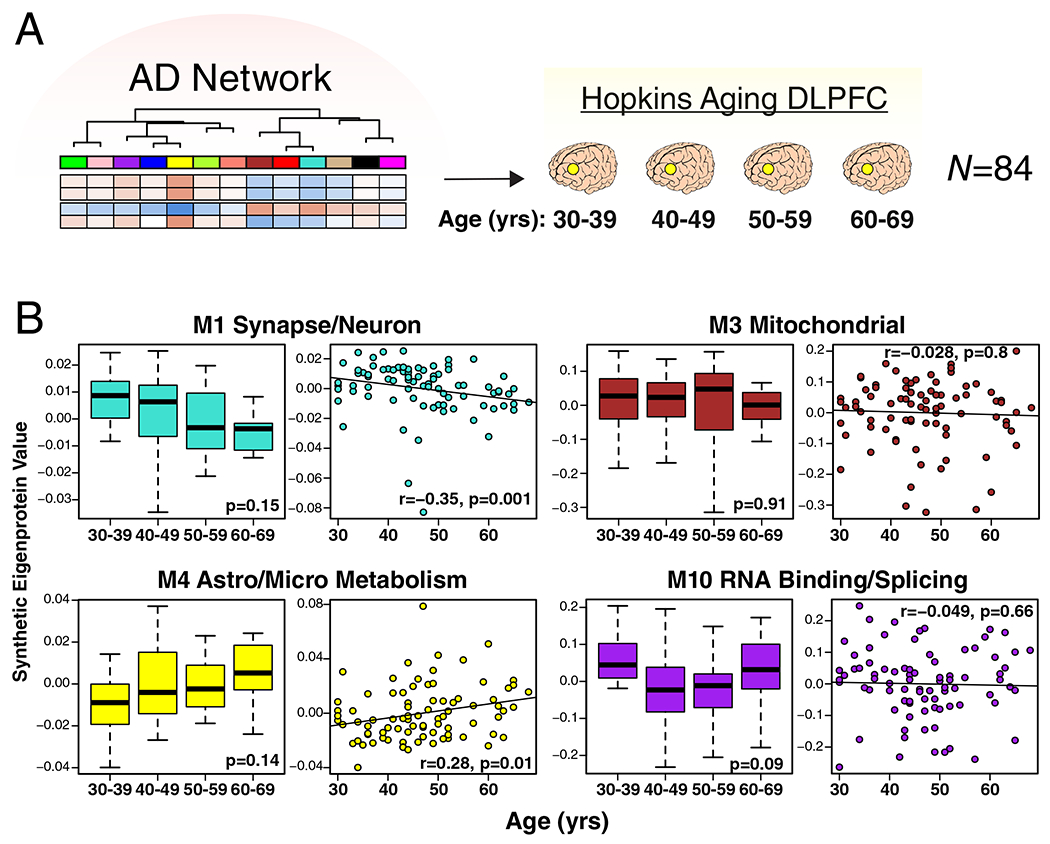

Effects of Aging on AD Network Modules

To better understand the influence aging—the strongest risk factor for AD—may have on the consensus AD network, we analyzed DLPFC tissues from Johns Hopkins in 84 cases ages 30 to 69 (Figure 3A) by LFQ-MS. All cases had a final primary neuropathological diagnosis of control. We created synthetic eigenproteins in the aging cohort from the consensus AD network modules and asked whether the synthetic module eigenproteins changed with age (Figure 3B and Supplementary Figure 9). We found that the M1 synapse/neuron and M4 astrocyte/microglial metabolism modules decreased and increased with aging, respectively, while the M3 mitochondrial and M10 RNA binding/splicing modules were not affected by aging. Other modules that appeared to be affected by aging included the M6 cytoskeleton, M7 translation/ribosome, and M9 translation/ribosome modules (Supplementary Figure 9). Additional information on the correlation of individual proteins with age and overlap with markers of cellular senescence is provided in Supplementary Table 3. These findings indicate that the relationship between aging and AD at the proteomic level is complex, and that some, but not all, AD trait-associated modules are influenced by the aging process.

Figure 3. Effects of Aging on AD Protein Network Modules.

(A, B) Protein levels were measured in DLPFC from cognitively normal people who died at different ages (age 30–39, n=20; age 40–49, n=34; age 50–59, n=17; age 60–69, n=13), and used to analyze AD protein network module changes with age. Brains were obtained from Johns Hopkins University. (B) A synthetic eigenprotein was created for each AD network module as described in Extended Data Figure 5 and measured by age group (left boxplot) as well as correlated with age (right scatterplot) in the aging brain cohort. Synthetic eigenprotein analyses for modules M1, M3, M4, and M10 are shown. Analyses for all modules are provided in Supplementary Figure 9. Differences in module synthetic eigenproteins by age grouping were assessed by Kruskal-Wallis one-way ANOVA. Synthetic eigenprotein correlations were performed using biweight midcorrelation. Boxplots represent the median, 25th, and 75th percentiles, and whiskers represent measurements to the 5th and 95th percentiles.

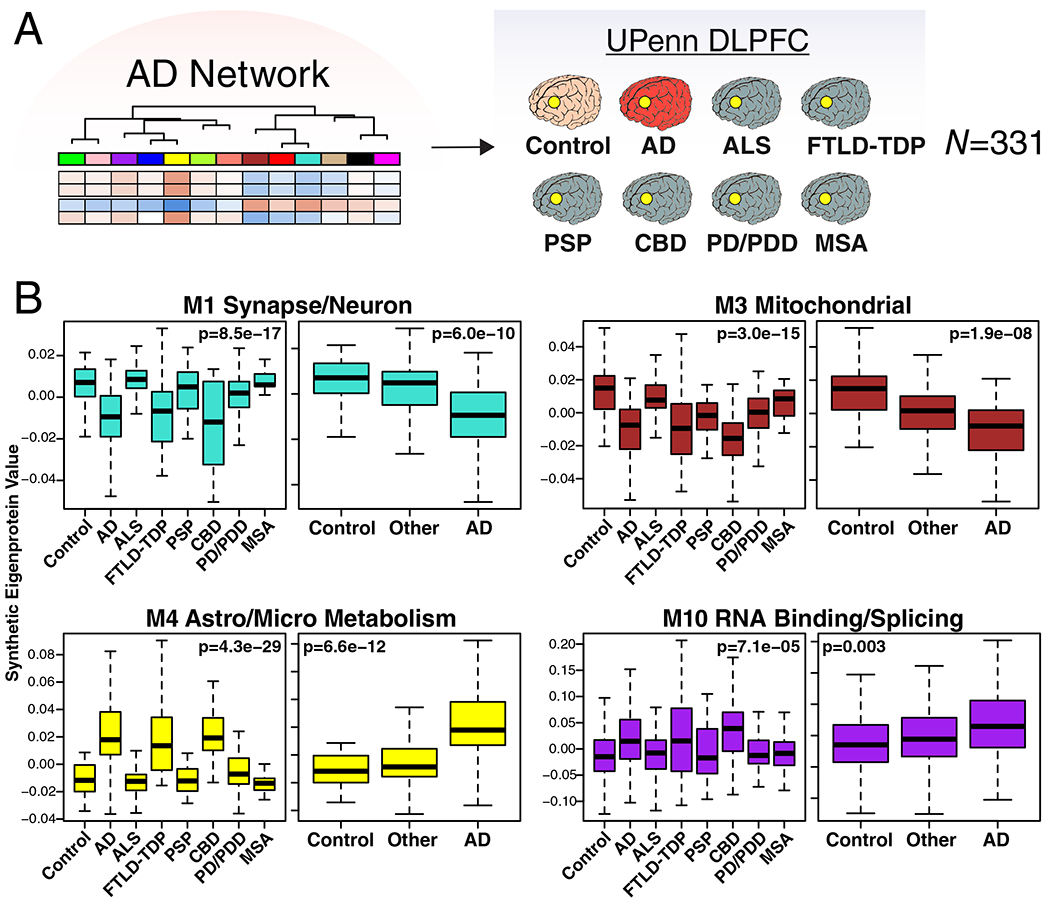

AD Network Changes in Other Neurodegenerative Diseases

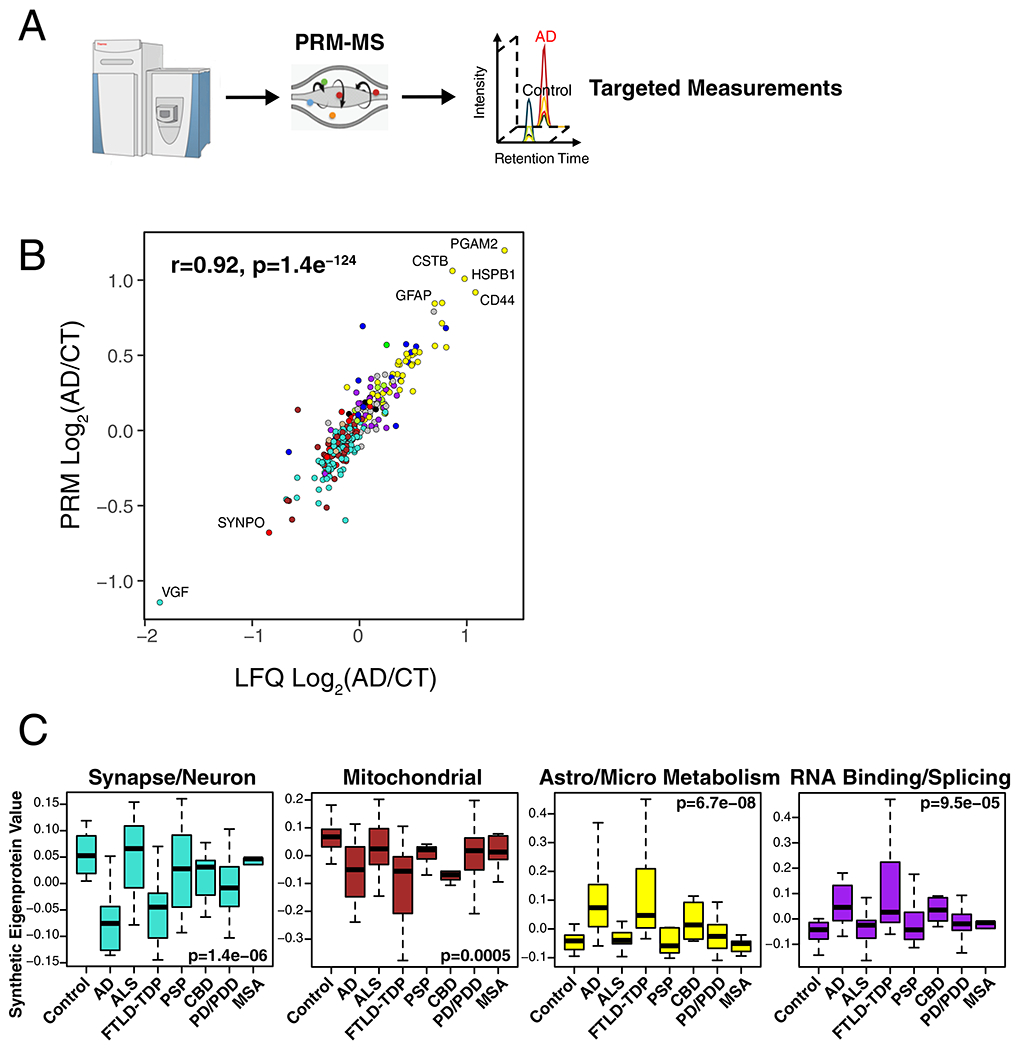

To explore the specificity of these network changes for AD, we analyzed 331 DLPFC tissues by LFQ-MS from control, AD, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), frontotemporal lobar degeneration with TDP-43 pathology (FTLD-TDP), progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP), corticobasal degeneration (CBD), Parkinson’s disease and Parkinson’s disease dementia (PD/PDD), and multiple systems atrophy (MSA) cases (Figure 4A). We created synthetic eigenproteins for consensus AD network modules and assessed whether they changed in these different neurodegenerative diseases compared to AD (Figure 4B, Supplementary Figure 10, Supplementary Table 4). We found that the M1 synapse/neuron and M4 astrocyte/microglial metabolism modules showed significant changes in FTLD-TDP and CBD cases, similar to AD, whereas the M3 mitochondrial and M10 RNA binding/splicing modules showed more mixed changes across other diseases. To further validate these findings, we used a targeted mass spectrometry method called parallel reaction monitoring (PRM)24 to measure 323 individual proteins from approximately one-third of the cases analyzed in the untargeted experiments (Supplementary Figure 11, Supplementary Table 4). Protein levels across all cases were highly correlated (r=0.92, p=1.4e−124) between LFQ and PRM measurements (Extended Data Figure 6B). We created synthetic eigenproteins from these targeted PRM protein measurements by AD consensus module, and assessed eigenprotein changes by disease category (Extended Data Figure 6C, Supplementary Figure 12, Supplementary Table 4). We observed very similar AD network module changes across diseases compared to the untargeted measurements, validating the findings from the untargeted LFQ measurements. These results indicate that certain AD network modules are affected to a greater extent in AD compared to other neurodegenerative diseases, and that FTLD and CBD show many similar changes to AD, with the caveat that not all neurodegenerative diseases affect the DLPFC region equally at end-stages of disease.

Figure 4. AD Protein Network Module Changes in Other Neurodegenerative Diseases.

(A, B) Protein levels were measured in DLPFC from control (n=46), AD (n=49), amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS, n=59), frontotemporal lobar degeneration with TAR DNA-binding protein 43 inclusions (FTLD-TDP, n=29), progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP, n=27), corticobasal degeneration (CBD, n=17), Parkinson’s disease and Parkinsons’s disease dementia (PD/PDD, n=81), and multiple system atrophy (MSA, n=23) cases from the University of Pennsylvania Brain Bank, and used to analyze AD protein network module changes in different neurodegenerative diseases. (B) A synthetic eigenprotein was created for each AD network module as described in Extended Data Figure 5 and measured by disease group in the UPenn cohort. Synthetic eigenprotein analyses for modules M1, M3, M4, and M10 are shown. Analyses for all modules are provided in Supplementary Figure 10. Differences in module synthetic eigenproteins were assessed by Kruskal-Wallis one-way ANOVA. Differences between AD and other case groups were assessed by two-sided Dunnett’s test, the results of which are provided in Supplementary Table 4. Boxplots represent the median, 25th, and 75th percentiles, and whiskers represent measurements to the 5th and 95th percentiles.

The M4 Astrocyte/Microglial Metabolism Module is Enriched in AD Genetic Risk Factors and Markers of Anti-Inflammatory Disease-Associated Microglia

We applied an algorithm to calculate a weighted disease risk score for proteins according to their linkage disequilibrium with AD-associated single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) discovered through AD genome wide association studies (GWAS)25. We then calculated whether a given AD network module was enriched in these risk factor proteins. We found that the M2 myelin/oligodendrocyte and M4 astrocyte/microglial metabolism modules were significantly enriched in gene products contained within AD risk factor loci (Figure 5A), suggesting that the biological functions or processes reflected by these protein co-expression modules may serve causative roles in AD.

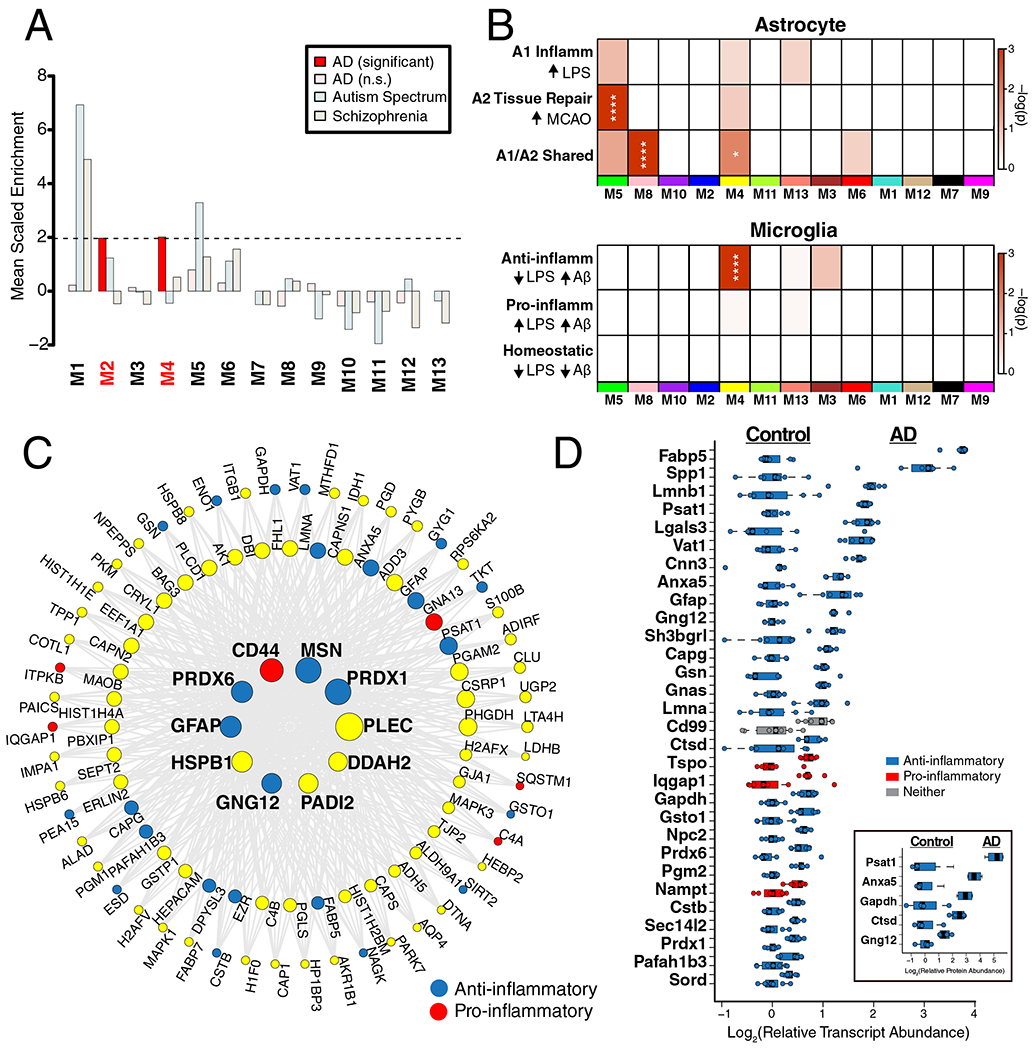

Figure 5. The M4 Astrocyte/Microglial Metabolism Module is Enriched in AD Genetic Risk Factors and Markers of Anti-Inflammatory Disease-Associated Microglia.

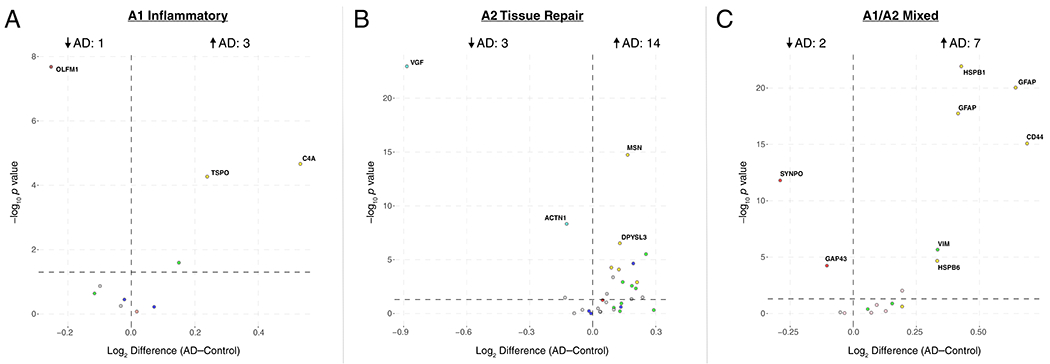

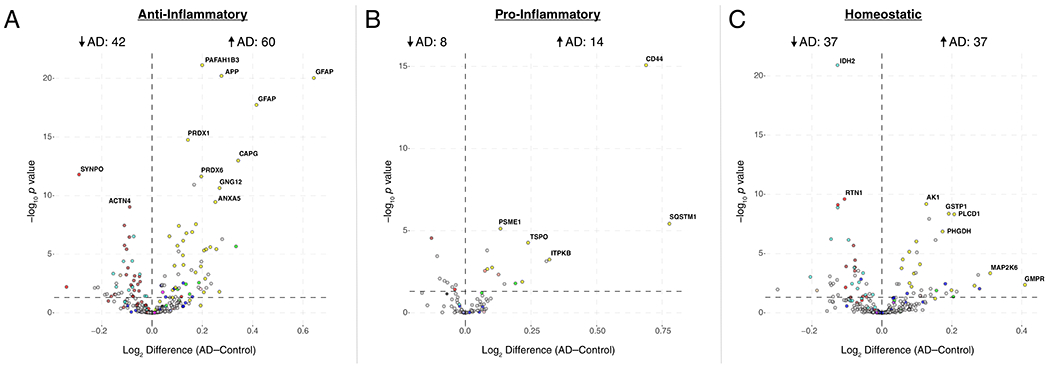

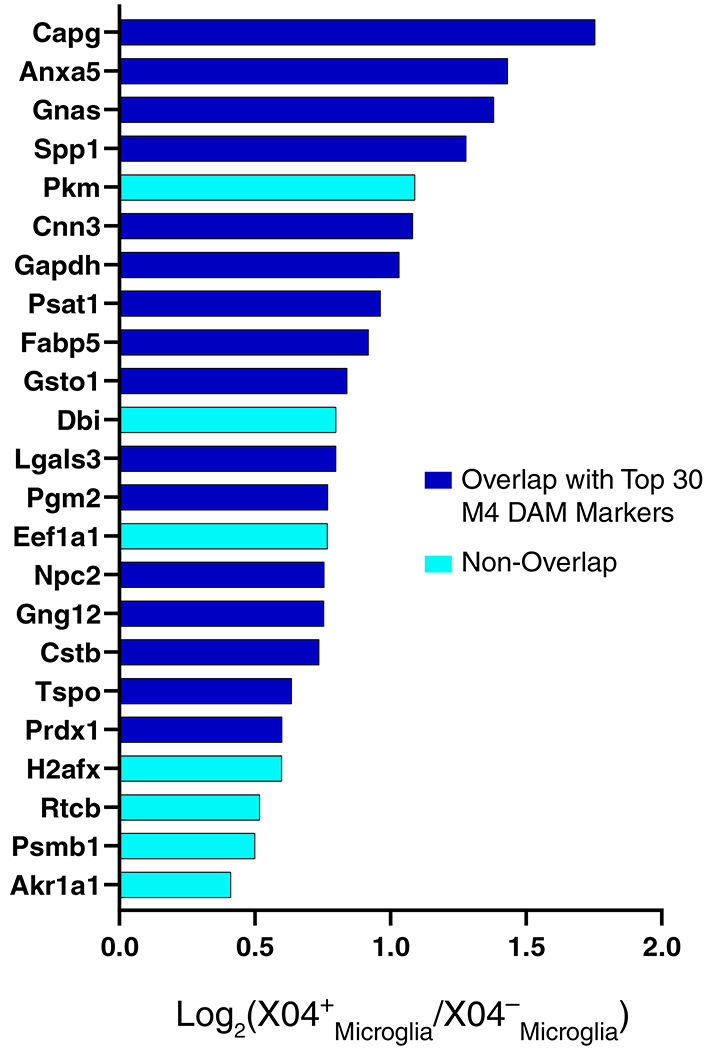

(A-D) Enrichment of proteins contained within genomic regions identified by genome wide association studies (GWAS) as risk factors for AD, autism spectrum disorder, and schizophrenia was calculated for each module in the AD protein network (A). Modules highlighted in dark red were significantly enriched for AD risk factors, and not for risk factors associated with autism spectrum disorders or schizophrenia. The horizontal dotted line indicates a z score level of enrichment of 1.96, or false discovery rate (FDR) q value <0.05, above which enrichment was considered statistically significant. Enrichment was calculated using the MAGMA algorithm, as previously described17, using module proteins provided in Supplementary Table 2 and 1234 genes identified as risk factors for AD74. (B) Enrichment of astrocyte (top) and microglia (bottom) phenotypic markers in AD protein network modules. (Top) Astrocyte phenotype markers indicating upregulation in response to acute injury with lipopolysaccharide (LPS) (A1 Inflammatory), middle cerebral artery occlusion (MCAO) (A2 Tissue repair), or both types of acute injury (A1/A2 Shared) in a mouse model26 were assessed for enrichment in AD network modules. (Bottom) Microglia markers from an mRNA co-expression analysis that are altered after challenge with LPS and/or amyloid-β plaque deposition in mouse models27 were assessed for enrichment in AD network modules (Anti-inflammatory, decrease with LPS administration and increase with plaque deposition; Pro-inflammatory, increase with LPS administration and increase with plaque deposition; Homeostatic, decrease with LPS administration and decrease with plaque deposition). Module enrichment was determined by one-sided Fisher’s exact test with Benjamini-Hochberg correction. Cell phenotype marker lists and protein module membership lists used for enrichment calculations are provided in Supplementary Table 5 and Supplementary Table 2, respectively. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.01, **** P < 0.0001. Exact P values are provided in Supplementary Table 5. (C) The top 100 proteins by module eigenprotein correlation value (kME) in module M4. The size of each circle indicates the relative kME. Those proteins with the largest kME are considered “hub” proteins within the module. Proteins highlighted in blue are upregulated in A2 tissue repair astrocyte and anti-inflammatory microglia; proteins highlighted in red are upregulated in A1 inflammatory astrocyte and pro-inflammatory microglia. Additional such proteins are provided in Supplementary Table 5. (D) The top 30 most differentially abundant microglial transcripts in an AD mouse model32 that overlap with proteins in the M4 module, colored as shown in (C) (n=7 APP/PS1 (AD) mice, n=7 wildtype (Cntl) mice). M4 proteins that overlap with transcripts elevated in microglia undergoing active amyloid-β plaque phagocytosis33 are provided in Extended Data Figure 10. (Inset) Transcript elevations validated at the protein level in microglia undergoing active amyloid-β plaque phagocytosis33 (n=4 5xFAD (AD) mice, n=4 wildtype (Cntl) mice). Boxplots represent the median, 25th, and 75th percentiles, and whiskers represent measurements to the 5th and 95th percentiles.

Given the strong AD trait associations of the M4 astrocyte/microglial metabolism module and its enrichment in AD genetic risk factors, we more deeply investigated the cell type nature of this co-expression module. Although expression of the M4 astrocyte/microglia metabolism module is increased with progression from a normal to an AD disease state, and a majority of the most significantly increased proteins in AD are members of this module (Extended Data Figure 7), it is unclear whether these glial responses are deleterious or protective. To better understand the role of these glial cell type responses in AD, we first examined differential expression of astrocyte and microglia protein markers in AD brain by the types of cellular phenotypes with which they are associated in AD animal models26–31. We found that for both astrocytic markers (Extended Data Figure 8) and microglial markers (Extended Data Figure 9), there appeared to be a bias towards expression of markers that are generally considered to be protective. We formally tested this observation with marker over-representation analysis in the AD network (Figure 5B, Supplementary Table 5). Microglial protein markers that are increased in response to amyloid-β plaques but decreased in response to LPS—or markers of anti-inflammatory disease-associated microglia27—were significantly enriched in the M4 module. Astrocyte markers were more mixed in module M4, with a majority of markers being shared between deleterious A1 and protective A2 phenotypes26. Astrocyte and microglia phenotype markers that overlap with the top 100 proteins by module eigenprotein correlation value in the M4 module are shown in Figure 5C. The majority of these markers were from microglia (Supplementary Table 5). To further validate these findings, we analyzed whether these markers were increased at both the transcript and protein levels in acutely isolated microglia from AD mouse models32,33. The top 30 most differentially abundant microglial transcripts corresponding to proteins in the M4 module were found to be heavily biased toward an anti-inflammatory phenotype (Figure 5D, Supplementary Table 5). Furthermore, many of the disease-associated M4 microglial protein markers were found to be increased in microglia undergoing active amyloid plaque phagocytosis (Extended Data Figure 10, Supplementary Table 5)33. In summary, we found that the M4 astrocyte/microglial metabolism module was enriched in AD genetic risk factors, and that microglia cell type markers within M4 appeared to be biased towards a protective anti-inflammatory, rather than a deleterious pro-inflammatory, microglial phenotype.

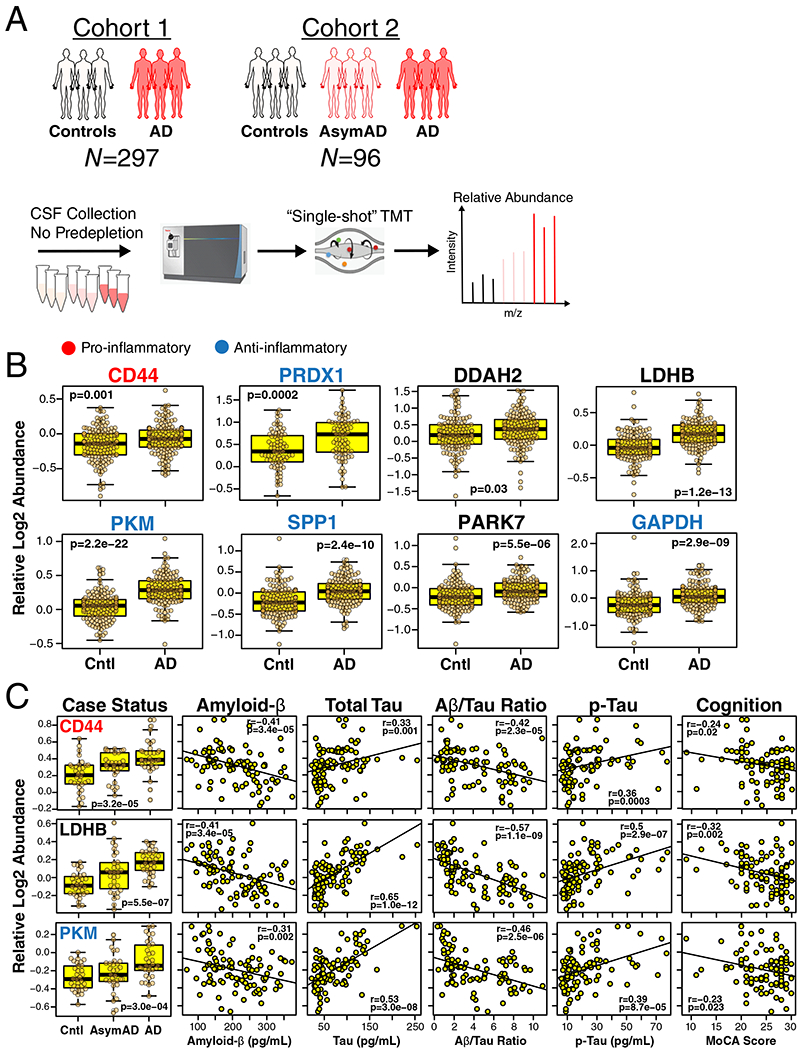

M4 Astrocyte/Microglial Metabolism Proteins Are Increased in Cerebrospinal Fluid

To explore whether proteins from the M4 astrocyte/microglial metabolism module might also be able to serve as AD fluid biomarkers, we analyzed CSF from two separate cohorts: one cohort of 297 subjects consisting of controls and AD patients (Cohort 1), and a second cohort of 96 subjects classified into control, AsymAD, and AD (Cohort 2). Subjects in both cohorts were classified by the “A/T/N” AD biomarker classification framework (Figure 6A)34. CSF from both cohorts was analyzed using a TMT-MS approach without prior pre-fractionation and without depletion of highly abundant proteins. In Cohort 1, we observed 22 proteins that mapped to the M4 astrocyte/microglial metabolism module in brain (Supplementary Figure 13). All of them showed either an increase in AD or no change, with 10 reaching statistical significance at p < 0.05. The most significantly increased M4 module proteins observed in Cohort 1 are shown in Figure 6B, and include the M4 hub proteins CD44, peroxiredoxin-1 (PRDX1), and dimethylarginine dimethylaminohydrolase-2 (DDAH2), in addition to the metabolic proteins lactate dehydrogenase B-chain (LDHB) and pyruvate kinase (PKM) involved in glycolysis. To validate these findings, and to assess whether the observed changes in CSF levels of M4 proteins occur prior to the development of cognitive impairment, we analyzed subjects in Cohort 2, approximately one-third of which had AsymAD. AsymAD was defined as CSF levels of amyloid-β, total tau, and phospho-tau consistent with an AD diagnosis, but without cognitive impairment. In Cohort 2, 27 proteins mapped to the M4 astrocyte/microglial metabolism module in brain (Supplementary Figure 14). Of these 27, 17 overlapped with M4 proteins measured in discovery Cohort 1, and showed the same direction of change in AD CSF. In addition, many also showed significant or trend elevations in AsymAD, including CD44, LDHB, and PKM, and correlated with cognitive function (Figure 6C). In summary, multiple M4 astrocyte/microglial metabolism module protein members could be measured in human CSF by mass spectrometry without fractionation or prior depletion of highly abundant proteins. A number of these proteins were elevated in AsymAD and AD, including M4 hub proteins CD44, PRDX1, and DDAH2.

Figure 6. M4 Astrocyte/Microglial Metabolism Module Protein Levels Are Elevated in AsymAD and AD CSF.

(A-C) Approach to analysis of M4 proteins in CSF from two different cohorts (A). CSF in Cohort 1 (n=297 biologically independent case samples) was obtained from subjects with normal CSF amyloid-β and tau levels (controls, n=150 case samples) and patients with low amyloid-β, elevated tau levels, and cognitive impairment (AD, n=147 case samples). CSF in Cohort 2 (n=96 biologically independent case samples) was obtained from control subjects (n=32 case samples) and AD patients (n=33 case samples) as defined in Cohort 1, as well as subjects with CSF amyloid-β and tau levels that met criteria for AD but who were cognitively normal at the time of collection (AsymAD, n=31 case samples). CSF was analyzed without prior pre-fractionation or depletion of highly abundant proteins; relative protein levels were measured by TMT-MS. (B) Relative CSF protein levels of selected M4 module members in Cohort 1. Protein names are colored according to pro-inflammatory (red) or anti-inflammatory (blue) classification. Proteins that are considered neither pro- nor anti-inflammatory are in black. Additional M4 protein measurements, as well as trait correlations for the measured proteins, are provided in Supplementary Figure 13. (C) Relative CSF protein levels of selected M4 module members in Cohort 2. Protein names are colored as in (B). Additional measurements and trait correlations are provided in Supplementary Figure 14. Differences in protein levels were assessed by two-sided Welch’s t test (B) or Kruskal-Wallis one-way ANOVA (C). Correlations were performed using biweight midcorrelation. Boxplots represent the median, 25th, and 75th percentiles, and whiskers represent measurements to the 5th and 95th percentiles. Cntl, control; AsymAD, asymptomatic Alzheimer’s disease; AD, Alzheimer’s disease; TMT, tandem mass tag; MoCA, Montreal Cognitive Assessment (higher scores represent better cognitive function).

Discussion

In this study, we analyzed more than 2000 brains by mass spectrometry-based proteomics to arrive at a consensus view of the proteomic changes that occur in brain during progression from normal to asymptomatic and symptomatic AD states. We find that the protein co-expression families most strongly correlated to disease reflect synaptic, mitochondrial, RNA binding/splicing, and astrocyte/microglial metabolism biological functions, with astrocyte/microglial metabolism most significantly associated with AD compared to other biological processes and functions. Increases in expression level of the M4 astrocyte/microglial metabolism module are observed with aging, but are stronger in AD, reflecting shared biology between “normal” aging and AD. The M4 module is enriched in AD genetic risk factors, indicating a potential causative role for this protein co-expression module in disease pathogenesis, and appears to serve a protective anti-inflammatory function in model systems, suggesting that genetic risk factor polymorphisms that cluster in this module may induce a loss-of-function phenotype. M4 astrocyte/microglial module proteins are increased in AsymAD and AD CSF, suggesting that proteins within the M4 module may serve as useful biomarkers for staging AD progression and for development of novel therapeutic approaches to the disease.

The protein co-expression modules we identified are not significantly influenced by regional tissue variation among temporal cortex, precuneus, and DLPFC brain regions. Indeed, we observed that all of the larger modules were highly preserved in both temporal cortex and precuneus, with preservation p values approaching zero in both regions. This suggests that the biological processes and cell types driving the co-expression patterns in AD brain are highly shared among these brain regions. Future proteomic analyses that include other brain regions less affected in late-onset AD (e.g., visual cortex) would be informative to further explore potential protective processes that may be important for regional vulnerability in AD. Also, emerging analyses that employ the use of newer mass spectrometry-based proteomic approaches, such as TMT-MS, that allow for prefractionation of brain tissues prior to analysis to increase the depth of proteome coverage will likely lead to identification of additional disease-related co-expression modules35–38. A recent proteomic study by Bai et al. on a smaller number of AD brains employed TMT-MS to deeply profile the AD brain proteome, and used network analysis to identify biological pathways altered in AD35. Cell type regression was performed prior to network analysis in Bai et al. from pooled samples, and therefore the protein network described here is not directly comparable to the one described in Bai et al. However, for those proteins in this study that overlap with the validated set of differentially expressed proteins in Bai et al. obtained after cell type regression, a majority are also differentially expressed in AD and map to the M4 module.

We assessed the disease specificity of the AD protein co-expression network by analyzing how the protein network modules changed in six other neurodegenerative diseases encompassing diverse brain pathologies. One caveat to this analysis is that we analyzed only DLPFC, which is not equally affected in all the neurodegenerative diseases we assessed. With this caveat in mind, we observed that FTLD-TDP and CBD had the most similar network changes to AD, suggesting that these clinicopathologic entities are fundamentally related to AD at the brain proteomic level. A proteomic relationship between AD and FTD is supported by the fact that mutations in the triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells 2 (TREM2) protein cause microglial dysfunction and lead to AD39,40, whereas mutations in the progranulin (PGRN) protein also cause microglial dysfunction and lead to FTD41–43. Further studies comparing frontal predominant AD, FTLD-TDP, and FTLD-tau cases would be informative to assess the degree to which the underlying neuropathology observed at autopsy is related to differences in proteomic network changes in the DLPFC region.

A key finding from our proteomic study is that glial biology—and microglial biology in particular—is a likely causal driver of AD pathogenesis. This finding is consistent with the results of other recent protein co-expression analyses of AD17,44. The AD protein network module most strongly associated with AD is enriched in astrocyte and microglial proteins, and is also enriched in proteins associated with genetic risk for AD. The M4 astrocyte/microglial metabolism module increases in AsymAD and correlates most strongly with cognitive impairment, suggesting that the biological changes reflected by this module occur early in the disease and have significant functional consequence on progression to dementia. A natural assumption would be that increases in M4 module expression levels are deleterious to brain health, and that potential therapies targeting reduction of M4 would likely be beneficial in AD. However, several lines of evidence support a possible protective role of this co-expression module. An important observation is that AD genetic risk alleles, which are more likely to cause loss-of-function changes rather than gain-of-function changes, are enriched in the M4 module. The M4 module is also enriched in microglial markers that are upregulated in response to amyloid-β deposition and downregulated in response to LPS, indicating that the microglial response as reflected in M4 module expression is likely biased towards an anti-inflammatory disease-associated phenotype27. Many M4 proteins are elevated in microglia that are undergoing plaque phagocytosis, which is consistent with the strong association of M4 expression with CERAD score. Notably, when we compare our findings to a prior proteomic study that quantified levels of plaque-associated proteins in normal versus rapidly-progressive AD45, 7 out of the top 10 plaque-associated proteins most significantly decreased in rapidly-progressive AD are found in the M4 module, including M4 hubs MSN and PLEC. This is consistent with the finding that early microglial activation in response to amyloid plaques, as assessed by in vivo microglial imaging studies, is correlated with increased grey matter volume and reduced rate of cognitive decline46,47. Interestingly, the degree of astrogliosis surrounding plaques seems to be positively correlated with improved cognitive function not only in AD, but also in normal aging individuals48. Taken together, these findings suggest that lack of an M4 astrocyte/microglial response to plaques in preclinical or clinical AD may lead to more rapid cognitive decline.

Many of the most significantly elevated M4 proteins in CSF are involved in glycolysis, including LDHB, PKM, and glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH). Elevations in PRDX1, DDAH, and protein/nucleic acid deglycase DJ-1 (PARK7) were also observed, all of which are important anti-oxidant effector proteins49–51 and are likely elevated in concert with increased glycolytic flux. LDHB, PKM, and DDAH1 have recently been reported as promising AD CSF biomarkers52,53. While M4 markers may not be entirely specific for AD given elevation of the M4 module in FTD and CBD, they may allow for assessment of an injury response in AD in conjunction with amyloid and tau biomarkers, and serve as useful biomarkers for other neurodegenerative dementias in addition to AD. Measurement of additional M4 markers in biofluids is undoubtedly possible, as our mass spectrometry measurements were performed on unfractionated CSF not depleted of highly abundant proteins. Indeed, recent studies have identified a number of additional potential biomarkers from M4 and other brain modules by deep mass spectrometry-based discovery on fractionated CSF35,36,54. Monitoring multiple M4 protein levels in biofluid may provide a robust measure of target engagement for AD therapies.

In summary, our comprehensive study on more than 2000 brains and nearly 400 CSF samples provides a consensus view of the proteomic network landscape of AD and the biological changes associated with asymptomatic and symptomatic stages of the disease, and highlights the central role of glial biology in the pathogenesis of the disease. Programs that target this biology hold promise for AD drug therapy and biomarker development, especially those that target pro- and anti-inflammatory astrocytes and microglia.

Methods

Brain Tissue Samples and Case Classification

Brain tissue used in this study was obtained from the autopsy collections of the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging55, Banner Sun Health Research Institute56, Mount Sinai School of Medicine Brain Bank, Adult Changes in Thought Study, Mayo Clinic Brain Bank, Religious Orders Study and Rush Memory and Aging Project57, University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine Brain Bank, and the Baltimore Coroner’s Office. Tissue was from the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (Brodmann Area 9 where available), or temporal cortex and precuneus regions where indicated. Human postmortem tissues were acquired under proper Institutional Review Board (IRB) protocols at each respective institution. Postmortem neuropathological evaluation of neuritic plaque distribution was performed according to the Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer’s Disease (CERAD) criteria15, while extent of spread of neurofibrillary tangle pathology was assessed with the Braak staging system58. Other neuropathologic diagnoses were made in accordance with established criteria and guidelines59. All case metadata, including age, sex, post-mortem interval, cognitive function, APOE genotype, neuropathological criteria, and disease status, are provided in Supplementary Table 1. Case classification harmonization across cohorts was performed using the following rubric: cases with CERAD 0-1 and Braak 0-3 without dementia at last evaluation were defined as control (if Braak equals 3, then CERAD must equal 0); cases with CERAD 1-3 and Braak 3-6 without dementia at last evaluation were defined as AsymAD; cases with CERAD 2-3 and Braak 3-6 with dementia at last evaluation were defined as AD. Dementia was defined as MMSE <24, CASI score <81, or CDR ≥1, based on prior comparative study60. Mayo and UPenn cases were not included in the case harmonization scheme, and therefore preservation of consensus network modules in these cohorts provides an additional degree of robustness.

Brain Tissue Homogenization and Protein Digestion

Procedures for tissue homogenization for all tissues were performed essentially as described17,21. Approximately 100 mg (wet tissue weight) of brain tissue was homogenize in 8 M urea lysis buffer (8 M urea, 10 mM Tris, 100 mM NaHPO4, pH 8.5) with HALT protease and phosphatase inhibitor cocktail (ThermoFisher) using a Bullet Blender (NextAdvance). Each Rino sample tube (NextAdvance) was supplemented with ~100 μL of stainless steel beads (0.9 to 2.0 mm blend, NextAdvance) and 500 μL of lysis buffer. Tissues were added immediately after excision and samples were then placed into the bullet blender at 4 °C. The samples were homogenized for 2 full 5 min cycles, and the lysates transferred to new Eppendorf Lobind tubes. Each sample was then sonicated for 3 cycles consisting of 5 s of active sonication at 30% amplitude, followed by 15 s on ice. Samples were then centrifuged for 5 min at 15,000 x g and the supernatant transferred to a new tube. Protein concentration was determined by bicinchoninic acid (BCA) assay (Pierce). For protein digestion, 100 μg of each sample was aliquoted and volumes normalized with additional lysis buffer. For the ROS/MAP cohort, an equal amount of protein from each sample was aliquoted and digested in parallel to serve as the global pooled internal standard (GIS) in each TMT batch, as described below. Similarly, GIS pooled standards were generated from the Banner, MSSB, Mayo, Aging, and UPenn cohorts. Samples were reduced with 1 mM dithiothreitol (DTT) at room temperature for 30 min, followed by 5 mM iodoacetamide (IAA) alkylation in the dark for another 30 min. Lysyl endopeptidase (Wako) at 1:100 (w/w) was added and digestion allowed to proceed overnight. Samples were then 7-fold diluted with 50 mM ammonium bicarbonate. Trypsin (Promega) was then added at 1:50 (w/w) and digestion was carried out for another 16 h. The peptide solutions were acidified to a final concentration of 1% (vol/vol) formic acid (FA) and 0.1% (vol/vol) trifluoroacetic acid (TFA), and desalted with a 30 mg HLB column (Oasis). Each HLB column was first rinsed with 1 mL of methanol, washed with 1 mL 50% (vol/vol) acetonitrile (ACN), and equilibrated with 2×1 mL 0.1% (vol/vol) TFA. The samples were then loaded onto the column and washed with 2×1 mL 0.1% (vol/vol) TFA. Elution was performed with 2 volumes of 0.5 mL 50% (vol/vol) ACN.

Mass Spectrometry Analysis for Label-free Proteomics

Mass spectrometry analyses of MSSB, ACT, BLSA, Banner, Mayo, and UPenn cohorts were performed on a Q-Exactive Plus mass spectrometer essentially as described17. Brain-derived tryptic peptides (2 μg) were resuspended in peptide loading buffer (0.1% FA, 0.03% TFA, 1% ACN) containing 0.2 pmol of isotopically labeled peptide calibrants (ThermoFisher 88321). Peptide mixtures were separated on a self-packed C18 (1.9 μm, Dr. Maisch, Germany) fused silica column (25 cm x 75 μM internal diameter; New Objective, Woburn, MA) by a NanoAcquity UHPLC (Waters, Milford, MA) and monitored on a Q-Exactive Plus mass spectrometer (ThermoFisher Scientific, San Jose, CA). Elution was performed over a 120 minute gradient at a rate of 400 nL/min with buffer B ranging from 3% to 80% (buffer A: 0.1% FA and 5% DMSO in water, buffer B: 0.1 % FA and 5% DMSO in ACN). The mass spectrometer cycle was programmed to collect one full MS scan followed by 10 data dependent MS/MS scans. The MS scans (300–1800 m/z range, 1,000,000 automatic gain control (AGC), 150 ms maximum ion time) were collected at a resolution of 70,000 at m/z 200 in profile mode, and the MS/MS spectra (2 m/z isolation width, 25% collision energy, 100,000 AGC target, 50 ms maximum ion time) were acquired at a resolution of 17,500 at m/z 200. Dynamic exclusion was set to exclude previous sequenced precursor ions for 30 seconds within a 10 ppm window. Precursor ions with +1 and +6 or higher charge states were excluded from sequencing.

Label-free Quantification

For the consensus LFQ search, 645 RAW files, including individual cases and pooled GIS samples from the MSSB, ACT, Banner and BLSA cohorts, were uploaded onto the Amazon Web Services (AWS) Cloud and analyzed using MaxQuant v1.6.3.4 with Thermo Foundation 2.0 for RAW file reading capability. The Mayo, BLSA precuneus, Aging, and UPenn cohorts were each searched separately using MaxQuant. The search engine Andromeda was used to build and search a concatenated target-decoy UniProt Knowledgebase (UniProtKB) containing both Swiss-Prot and TrEMBL human reference protein sequences (90,411 target sequences downloaded April 21, 2015), plus 245 contaminant proteins included as a parameter for the Andromeda search within MaxQuant. Methionine oxidation (+15.9949 Da), asparagine and glutamine deamidation (+0.9840 Da), and protein N-terminal acetylation (+42.0106 Da) were variable modifications (up to 5 allowed per peptide); cysteine was assigned a fixed carbamidomethyl modification (+57.0215 Da). Only fully tryptic peptides with up to 2 miscleavages were considered in the database search. A precursor mass tolerance of ±20 ppm was applied prior to mass accuracy calibration, and ±4.5 ppm after internal MaxQuant calibration. Other search settings included a maximum peptide mass of 6,000 Da, a minimum peptide length of 6 residues, and 0.05 Da tolerance for high resolution MS/MS scans. The false discovery rate (FDR) for peptide spectral matches, proteins, and site decoy fraction were each set to 1 percent. Quantification settings were as follows: re-quantify with a second peak-finding attempt after protein identification is complete; match full MS1 peaks between runs; use a 0.7 min retention time match window after an alignment function was found with a 20 minute retention time search space. The label free quantitation (LFQ) algorithm in MaxQuant61,62 was used for protein quantitation. The quantitation method considered only razor and unique peptides for protein level quantitation. The total summed protein intensity was also used to assess overall signal drift across samples prior to LFQ normalization.

Isobaric Tandem Mass Tag (TMT) Peptide Labeling of ROS/MAP Brain Tissues

Prior to TMT labeling, cases were randomized by covariates (age, sex, PMI, diagnosis, etc.), into 50 total batches (8 cases per batch). Peptides from each individual case (n=400) and the GIS pooled standard (n=100) were labeled using the TMT 10-plex kit (ThermoFisher 90406). In each batch, TMT channels 126 and 131 were used to label GIS standards, while the 8 middle TMT channels were reserved for individual samples following randomization. Labeling was performed as previously described21,37. Briefly, each sample (containing 100 μg of peptides) was re-suspended in 100 mM TEAB buffer (100 μL). The TMT labeling reagents were equilibrated to room temperature, and anhydrous ACN (256 μL) was added to each reagent channel. Each channel was gently vortexed for 5 min, and then 41 μL from each TMT channel was transferred to the peptide solutions and allowed to incubate for 1 h at room temperature. The reaction was quenched with 5% (vol/vol) hydroxylamine (8 μl) (Pierce). All 10 channels were then combined and dried by SpeedVac (LabConco) to approximately 150 μL and diluted with 1 mL of 0.1% (vol/vol) TFA, then acidified to a final concentration of 1% (vol/vol) FA and 0.1% (vol/vol) TFA. Peptides were desalted with a 200 mg C18 Sep-Pak column (Waters). Each Sep-Pak column was activated with 3 mL of methanol, washed with 3 mL of 50% (vol/vol) ACN, and equilibrated with 2×3 mL of 0.1% TFA. The samples were then loaded and each column was washed with 2×3 mL 0.1% (vol/vol) TFA, followed by 2 mL of 1% (vol/vol) FA. Elution was performed with 2 volumes of 1.5 mL 50% (vol/vol) ACN. The eluates were then dried to completeness using a SpeedVac.

High-pH Off-line Fractionation of ROS/MAP Brain Tissues

High pH fractionation was performed essentially as described63 with slight modification. Dried samples were re-suspended in high pH loading buffer (0.07% vol/vol NH4OH, 0.045% vol/vol FA, 2% vol/vol ACN) and loaded onto an Agilent ZORBAX 300 Extend-C18 column (2.1mm x 150 mm with 3.5 μm beads). An Agilent 1100 HPLC system was used to carry out the fractionation. Solvent A consisted of 0.0175% (vol/vol) NH4OH, 0.01125% (vol/vol) FA, and 2% (vol/vol) ACN; solvent B consisted of 0.0175% (vol/vol) NH4OH, 0.01125% (vol/vol) FA, and 90% (vol/vol) ACN. The sample elution was performed over a 58.6 min gradient with a flow rate of 0.4 mL/min. The gradient consisted of 100% solvent A for 2 min, then 0% to 12% solvent B over 6 min, then 12% to 40 % over 28 min, then 40% to 44% over 4 min, then 44% to 60% over 5 min, and then held constant at 60% solvent B for 13.6 min. A total of 96 individual equal volume fractions were collected across the gradient and subsequently pooled by concatenation63 into 24 fractions and dried to completeness using a SpeedVac.

TMT Mass Spectrometry of ROS/MAP Brain Tissues

All fractions were resuspended in an equal volume of loading buffer (0.1% FA, 0.03% TFA, 1% ACN) and analyzed by liquid chromatography coupled to tandem mass spectrometry essentially as described64, with slight modifications. Peptide eluents were separated on a self-packed C18 (1.9 μm, Dr. Maisch, Germany) fused silica column (25 cm × 75 μM internal diameter (ID); New Objective, Woburn, MA) by an Dionex UltiMate 3000 RSLCnano liquid chromatography system (ThermoFisher Scientific) and monitored on an Orbitrap Fusion mass spectrometer (ThermoFisher Scientific). Sample elution was performed over a 180 min gradient with flow rate at 225 nL/min. The gradient was from 3% to 7% buffer B over 5 min, then 7% to 30% over 140 min, then 30% to 60% over 5 min, then 60% to 99% over 2 min, then held constant at 99% solvent B for 8 min, and then back to 1% B for an additional 20 min to equilibrate the column. Buffer A was water with 0.1% (vol/vol) formic acid, and buffer B was 80% (vol/vol) acetonitrile in water with 0.1% (vol/vol) formic acid. The mass spectrometer was set to acquire in data dependent mode using the top speed workflow with a cycle time of 3 seconds. Each cycle consisted of 1 full scan followed by as many MS/MS (MS2) scans that could fit within the time window. The full scan (MS1) was performed with an m/z range of 350–1500 at 120,000 resolution (at 200 m/z) with AGC set at 4×105 and maximum injection time 50 ms. The most intense ions were selected for higher energy collision-induced dissociation (HCD) at 38% collision energy with an isolation of 0.7 m/z, a resolution of 30,000, an AGC setting of 5×104, and a maximum injection time of 100 ms. Five of the 50 TMT batches were run on the Orbitrap Fusion mass spectrometer using the SPS-MS3 method as previously described21.

TMT ROS/MAP Database Searches and Protein Quantification

All RAW files (1,200 RAW files generated from 50 TMT 10-plexes) were analyzed using the Proteome Discoverer suite (version 2.3, ThermoFisher Scientific). MS2 spectra were searched against the UniProtKB human proteome database containing both Swiss-Prot and TrEMBL human reference protein sequences (90,411 target sequences downloaded April 21, 2015), plus 245 contaminant proteins. The Sequest HT search engine was used and parameters were specified as follows: fully tryptic specificity, maximum of two missed cleavages, minimum peptide length of 6, fixed modifications for TMT tags on lysine residues and peptide N-termini (+229.162932 Da) and carbamidomethylation of cysteine residues (+57.02146 Da), variable modifications for oxidation of methionine residues (+15.99492 Da) and deamidation of asparagine and glutamine (+0.984 Da), precursor mass tolerance of 20 ppm, and a fragment mass tolerance of 0.05 Da for MS2 spectra collected in the Orbitrap (0.5 Da for the MS2 from the SPS-MS3 batches). Percolator was used to filter peptide spectral matches (PSMs) and peptides to a false discovery rate (FDR) of less than 1%. Following spectral assignment, peptides were assembled into proteins and were further filtered based on the combined probabilities of their constituent peptides to a final FDR of 1%. In cases of redundancy, shared peptides were assigned to the protein sequence in adherence with the principles of parsimony. Reporter ions were quantified from MS2 or MS3 scans using an integration tolerance of 20 ppm with the most confident centroid setting.

Parallel Reaction Monitoring (PRM) Analysis

Peptides from brain digests used for the first 3 batches of the untargeted UPenn cohort analysis (equal to 1 μg protein digestion) were used for targeted analysis on an Orbitrap Lumos™ Tribrid™ Mass Spectrometer (ThermoFisher Scientific) fitted with a Nanospray Flex ion source and coupled to a NanoAcuity liquid chromatography system (Waters). The tryptic peptides were resuspended in loading buffer (0.1% TFA, 500 ng/μl), and an external reference peptide mix (Promega) was spiked into the sample at the concentration of 0.5 pmol/μl. The solution (2 μl) was loaded onto a self-packed 1.9 μm ReproSil-Pur C18 (Dr. Maisch) analytical column (New Objective, 50 cm × 75 μm inner diameter; 360 μm outer diameter) heated to 60 °C. The capillary temperature and spray voltage was set at 300 °C and 2.0 kV, respectively. Elution was performed over a 100 min gradient at a rate of 350 nL/min with buffer B ranging from 1% to 32% (buffer A: 0.1% FA in water, buffer B: 0.1% FA in ACN). The column was then washed with 99% buffer B for 10 minutes and equilibrated with 1% B for 15 minutes. The mass spectrometer was set to collect in PRM mode using an inclusion peptide list (Supplementary Table 4). An additional full survey scan was collected to assess for possible interference. Full scans were collected at a resolution of 120,000 at 200 m/z with an AGC setting of 2×105 ion and a maximum ion transfer (IT) time of 50 ms. For PRM scans, the settings were: resolution at 30,000 at 200 m/z, AGC target of 1×105 ions, maximum IT time of 50 ms, microscans count of 1, isolation width of 1.6 m/z, and isolation offset of 0 m/z. A pre-optimized normalized collision energy of 32% was used to obtain the maximal recovery of target product ions. The top 5–10 product ions from this collision energy optimization were used for downstream peptide quantification.

Peptide Quantification

A spectral library was built using Skyline (version 4.2) based on tandem mass spectra gathered from previous data dependent acquisition methods. A Skyline template was then created to quantify the endogenous peptides. The template parameters were: centroided precursor mass analyzer, MS1 mass accuracy of 20 ppm; centroided product mass analyzer, MS/MS mass accuracy of 20 ppm; include all matching scans. All rawfiles were then imported and processed accordingly. The resulting extracted ion chromatograms (XICs) of selected fragments were manually inspected and peak picking adjustments were made accordingly. The sum of all product ion peak areas was calculated in Skyline and extracted for further statistical analyses. The peak areas were normalized using the peak areas of external reference peptides. Raw peptide intensities are provided at https://www.synapse.org/consensus.

Selected Reaction Monitoring (SRM) of ROS/MAP Brain Tissues

Samples were prepared for LC-SRM analysis using a standard protocol described elsewhere65. Briefly, on average ~20 mg of DLPFC brain tissue from each subject was homogenized in denaturation buffer. After denaturation with DTT, 400 μg protein aliquots were taken for further alkylation with iodoacetamide followed by digestion with trypsin as described. The digests were cleaned using C18 solid phase extraction, and 30 μL aliquots at 1 μg/μL concentrations were mixed with 30 μL synthetic peptide mix. LC-SRM experiments were performed on a nanoACQUITY UPLC (Waters) coupled to a TSQ Vantage mass spectrometer (ThermoScientific), with 2 μL of peptide injection for each brain sample. Buffer A was 0.1% FA in water and buffer B was 0.1% FA in 90% ACN. Peptide separations were performed on an Acquity UPLC BEH 1.7 μm C18 column (75 μm i.d. × 25 cm) at a flow rate 350 nL/min using a gradient of 0.5% buffer B over 0 to 14.5 min, then 0.5% to 15% over 14.5 to 15.0 min, then 15% to 40% over 15 to 30 min, and then 45% to 90% B over 30 to 32 min. The heated capillary temperature and spray voltage was set at 350 °C and 2.4 kV, respectively. Both the Q1 and Q3 were set as 0.7 FWHM. A scan width of 0.002 m/z and a dwell time of 10 ms were used. All SRM data were analyzed using the Skyline software package. All data were manually inspected to ensure correct peak assignment and peak boundaries. The peak area ratios of endogenous light peptides and their heavy isotope-labeled internal standards (i.e., L/H peak area ratios) were then automatically calculated by the Skyline software, and the best transition without matrix interference was used for accurate quantification. Following homogenization of all tissues, small aliquots of protein from each of the samples was pooled, which were then digested and served as a global external pooled reference standard. Peptides generated from this pooled standard were scattered throughout the study (8 samples per 96-well plate) and were used to capture the technical variance that is due to sample preparation steps (except homogenization) and instrument measurements. The signal-to-noise ratio in quantification of each peptide was calculated as the ratio of variances across the human subject samples versus the technical controls. Peptides with a signal-to-noise ratio less than 2 were excluded from further analysis. The peptide relative abundances were log2 transformed and centered at the median. The abundance of endogenous peptides was quantified as a ratio to spiked-in synthetic peptides containing stable heavy isotopes. The “light/heavy” ratios were log2 transformed and shifted such that median log2-ratio was zero. Normalization adjusted for differences in protein amounts among the samples. During normalization, the log2-ratios were shifted for each sample to make sure the median was set at zero.

CSF Samples

All participants from whom CSF samples were collected provided informed consent under protocols approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) at Emory University. All patients received standardized cognitive assessments (including MoCA) in the Emory Cognitive Neurology clinic, the Emory Goizueta Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center (ADRC), and affiliated research studies (Emory Healthy Brain Study [EHBS] and Emory M2OVE-AD study). All diagnostic data were supplied by the ADRC and the Emory Cognitive Neurology Program. CSF was collected by lumbar puncture and banked according to 2014 ADC/NIA best practices guidelines. For patients recruited from the Emory Cognitive Neurology Clinic, CSF samples were sent to Athena Diagnostics and assayed for Aβ42, total-Tau, and phospho-Tau (CSF ADmark®) using the INNOTEST® assay platform. CSF samples collected from research participants in the ADRC, EHBS, and M2OVE-AD were assayed using the INNO-BIA AlzBio3 Luminex assay. In total, there were two cohorts of CSF samples that were used in the proteomics studies. Cohort 1 contained CSF samples from 150 healthy controls and 147 MCI/AD patients. Cohort 2 included CSF obtained from three groups: 32 cognitively normal, 31 AsymAD, and 33 MCI/AD. Cases and normal individuals with AsymAD were defined using established biomarker cutoff criteria for AD for each assay platform66,67. Cohort information is provided in Supplementary Table 1.

CSF Protein Digestion

To generate peptides, all crude CSF samples were digested with LysC and trypsin. Briefly, 20 μL CSF from each sample was reduced and alkylated with 0.4 μL 0.5 M tris-2(-carboxyethyl)-phosphine (TCEP) and 2 μL 0.4 M chloroacetamide (CAA) with heating at 90°C for 10 min, followed by a 15 min water bath sonication. The samples were then further denatured by the addition of 67.2 μL of 8 M urea buffer (8 M urea, 100 mM NaHPO4, pH 8.5) and digested overnight with 1.9 μg LysC (Wako) (1:10 enzyme to protein ratio according to the highest amount of sample). Following LysC digestion, the samples were diluted to 1 M urea using 50 mM ammonium bicarbonate. The same amount of trypsin (Promega) was then added (1:10 enzyme to protein ratio) and digestion was carried out for another 12 h. After trypsin digestion, the peptide solutions were acidified with a 1% TFA and 10% FA solution to a final concentration of 0.1% TFA and 1% FA. Peptides were desalted with a 30 mg C18 HLB column (Waters) and eluted in 1 mL of 50% ACN. Aliquots (120 μL) from cohort 1 (n=297) or cohort 2 (n=96) samples were pooled together and split into equal volume aliquots (880 μL) for use as the global internal standard (GIS) for TMT labeling. All samples and GIS were dried using a SpeedVac.

TMT Boost Channel

Signals of low abundant proteins in the TMT 11-plex were amplified using a boost channel, as previously described68. A pooled CSF sample was created separately for each cohort by combining 50 μL from each sample in cohort 1 or cohort 2 into a pool for each cohort. Abundant proteins were removed using the High Select Top14 Abundant Proteins Depletion Resin (Thermo Scientific A36372BR) according to the manufacturer’s protocol, using a CSF-to-resin volume ratio of 1:1 and an incubation time of 15 min. After immunodepletion, protein concentrations were determined by BCA. Proteins were then reduced and alkylated (10 mM TCEP, 40 mM CAA) for 10 minutes at 90 °C. The samples were then subjected to bath sonication for 15 min and dried under vacuum in a SpeedVac. The immunodepleted pooled samples were re-suspended in 6 M urea buffer (6 M urea, 75 mM NaHPO4, pH 8.5) at half the volume of the pooled sample prior to evaporation. Samples were digested overnight with LysC at an enzyme to protein ratio of 1:10. The following day, samples were diluted with 50 mM ammonium bicarbonate to reduce the urea concentration to 1M, and trypsin (Promega) was added (1:10 enzyme to protein ratio). Digestion was allowed to proceed for 12 hr. Peptides were then desalted using a 200 mg C18 Sep-Pak column, and the eluate was dried using a SpeedVac. Aliquots (600 μg) of the immunodepleted pooled CSF samples were separately dissolved in 100 mM TEAB buffer (625 μL) and labeled with 5 mg of TMT 126 channel reagent (cohort 1 lot# TF266326, cohort 2 lot# SG253447, ThermoFisher Scientific) in anhydrous ACN (256 μL). The reactions were allowed to proceed for 1 hr, and were subsequently quenched by adding 5% hydroxylamine (50 μL) and incubating for 15 min. The 126 channel was then added to the other channels, as described below.

TMT Labeling of Individual and GIS CSF Samples

All samples, including the GIS, were labeled with the 10-plex TMT kit plus an additional channel, for a total of 11 TMT channels (cohort 1 lot# TG273545 for 10-plex, TG273555 for channel 131C; cohort 2 lot# SI258088 for 10-plex, SJ258847 for channel 131C, ThermoFisher Scientific). Samples were grouped into batches as shown in Supplementary Table 1. The TMT labeling kit was equilibrated to room temperature and dissolved in anhydrous ACN (256 μL). The samples were reconstituted in 100 mM TEAB buffer (50 μL) and mixed with 0.4 mg (20.5 μL) of the corresponding labeling reagent. The labeling reactions were allowed to proceed for 1 hr, and were subsequently quenched with 5% hydroxylamine (4 μL). Per each TMT batch, labeled peptides from 9 channels (127N, 128N, 128C, 129N, 129C, 130N, 130C, 131, 131C) were mixed, desalted using a 100 mg C18 Sep-Pak column, and dried using a SpeedVac. The immunodepleted pooled sample labeled with the 126 channel (boost channel) was then added to each 9-channel TMT mixture at a ratio of 50:1 pooled to individual CSF sample by original volume:volume prior to evaporation. The sample mixtures were desalted using a 200 mg C18 Sep-Pak column, and dried using a SpeedVac.

Mass Spectrometry Analysis of CSF

All samples were resuspended in equal volume of loading buffer (0.1% FA, 0.03% TFA, 1% ACN). Peptide eluents were separated on a self-packed C18 (1.9 μm, Dr. Maisch, Germany) fused silica column (25 cm × 75 μM internal diameter (ID): New Objective, Woburn, MA) by an Easy-nLC system (ThermoFisher Scientific) and monitored on an Orbitrap Fusion Lumos mass spectrometer (ThermoFisher Scientific) interfaced with a high-field asymmetric waveform ion mobility spectrometry (FAIMS) Pro. Sample elution was performed over a 180 min gradient (buffer A: 0.1% FA in water, buffer B: 0.1% FA in 80% ACN) with flow rate at 225 nL/min. The gradient was from 1% to 8% buffer B over 3 min, then from 8% to 40% over 160 min, then from 40% to 99% over 10 min, and then held at 99% B for 10 min. The mass spectrometer was set to acquire data in positive ion mode using data dependent acquisition and three (−50, −65 and −85 V) different compensation voltages (CV). Data were acquired at each CV for 1 s during each cycle. Each cycle consisted of 1 full scan followed by as many MS2 and MS3 scans as possible within a 1 s timeframe. The full scan was performed with an m/z range of 450–1500 at 120,000 resolution (at 200 m/z) with an AGC setting of 4×105 and maximum injection time 50 ms. The collision induced dissociation (CID) MS/MS scans were collected in the ion trap with an isolation window of 0.7 m/z, a collision energy of 35%, AGC setting of 1×104, and a maximum injection time of 50 ms. The top 10 product ions were subjected to HCD synchronous precursor selection-based MS3 (SPS-MS3) as previously described21. For SPS-MS3 scans the isolation window was set to 2 m/z, the resolution to 50,000, the AGC to 1×105, and the maximum injection time to 105 ms. For both cohorts, a single preliminary run of TMT batch 1 using the above parameters was used to create a target inclusion list of peptides that specifically excluded those from the top 15 most abundant proteins. This inclusion list was used for all TMT batches in cohort 1 (n=38) and in cohort 2 (n=12).

Database Searches and Protein Quantification of CSF

All RAW files were analyzed using the Proteome Discoverer Suite (version 2.3, ThermoFisher Scientific). MS/MS spectra were searched against the UniProtKB human proteome database (downloaded April 2015 with 90,411 total sequences). The Sequest HT search engine was used to search the RAW files, with search parameters specified as follows: fully tryptic specificity, maximum of two missed cleavages, minimum peptide length of 6, fixed modifications for TMT tags on lysine residues and peptide N-termini (+229.162932 Da) and carbamidomethylation of cysteine residues (+57.02146 Da), variable modifications for oxidation of methionine residues (+15.99492 Da), serine, threonine and tyrosine phosphorylation (+79.966 Da) and deamidation of asparagine and glutamine (+0.984 Da), precursor mass tolerance of 20 ppm, and a fragment mass tolerance of 0.6 Da. Percolator was used to filter PSMs and peptides to an FDR of less than 1%. Following spectral assignment, peptides were assembled into proteins and were further filtered based on the combined probabilities of their constituent peptides to a final FDR of 1%. In cases of redundancy, shared peptides were assigned to the protein sequence in adherence with the principles of parsimony. Reporter ions were quantified from MS3 scans using an integration tolerance of 20 ppm with the most confident centroid setting, as previously described21.

Controlling for Batch-specific Variance

We implemented a median polish algorithm for removing technical variance (e.g., due to tissue collection, cohort, or batch effects) from a two-way abundance-sample data table as originally described by Tukey69. The algorithm is fully documented and available as an R function, which can be downloaded from https://github.com/edammer/TAMPOR. The algorithm implements iterations of the below equation, where batch and cohort are interchangeable.

| [Eq. 1] |

Briefly, Equation 1 is applied to each protein measurement (LFQ or TMT reporter abundance) across all samples individually where the first term represents batch-wise median-centered abundance, and the second term is a batch-specific normalization factor comprised of the grand median of all batch-specific medians, divided by the appropriate batch-specific median of median-centered abundances. The data matrix is then log2-transformed, and each log2(ratio) is adjusted by subtraction of sample (column)-wise median log2(ratio) for all proteins. Then, ratios are anti-logged and multiplied by the protein (row)-wise median of all samples used for the Eq. 1, term 1, denominator, extracted before Eq. 1 was executed. This process is iterated until convergence. The use of median polish ensures that the reduction of variance is robust to outliers while the overall algorithm preserves biological variance, given that batches have been randomized to avoid confounding batch with diagnosis or other biological traits. Prior to matrix assembly for the consensus analysis, intra-cohort batch effects were first removed in the MSSB (batch correction with 166 case samples across 7 batches) and Banner (batch correction with 178 case samples across 4 batches) cohorts. All remaining batch corrections restricted the first term denominator to global pooled (within cohort) standard sample abundances, and the second term used all individual case samples. Following removal of intra-cohort batch effects in MSSB and Banner, all samples were processed jointly with the algorithm in the same sample-protein matrix to capture biological variance across all samples in all four cohorts (ACT, Banner, BLSA, and MSSB) for the consensus analysis. The above algorithm was applied to a matrix in which proteins that had ≥ 50% missing values were removed. For the consensus LFQ network, 450 case samples (3 ACT outliers were removed prior to inclusion, as described below) classified as control, AsymAD, or AD by our unified criteria (see case classification methods above) were considered as “all samples” for denominators in Eq. 1. All remaining batch corrections listed as follows restricted the first term denominator to global pooled (within cohort) standard sample abundances, and the second term used all individual case samples.

For ROSMAP 50-batch TMT protein abundances, there were two pooled global internal standard channels in each TMT batch (n=64), and 400 individual case samples (non-internal standard samples). For the Hopkins aging cohort (84 case samples), global pool mixture samples (3 each per 3 batches) were used for the first term denominator, with the second term using all non-global pool mixture samples. For the UPenn PRM analysis (3 batches, 114 case samples, and 9 pooled controls), data were likewise batch corrected using 3 global pool mixture samples per batch for the first term denominator and all within-batch non-pooled samples for the second term. UPenn LFQ data (10 batches, 330 case samples, and 29 control pools) were similarly batch corrected as described. CSF 96-case and 300-case TMT normalized abundances were also batch corrected using the above algorithm, with equation 1 first term denominator restricted to global pooled (within cohort) standard sample abundances, while the second term used all individual non-internal standard case samples.

Regression for Covariates and Outlier Removal

No imputation of missing values was performed in any cohort. Nonparametric bootstrap regression was performed separately in each cohort by subtracting the trait of interest (age at death, sex, or postmortem interval (PMI)) times the median estimated coefficient from 1000 iterations of fitting for each protein in the cohort-specific log2(abundance) matrix. Ages at death used for regression were uncensored. Case status/diagnosis was also explicitly modeled (i.e., protected) in each regression. Following regression of each individual cohort, we assessed whether any cohort-specific tissue dissection bias was present by performing a Spearman rank correlation of traits including age, sex, PMI, and white matter markers to the top five principle components (PC) of log2(abundance). Network outlier case samples were not considered in the PCs, and were identified prior to PC analysis using Oldham’s ‘SampleNetworks’ v1.06 R script4 as previously published70 using a 3 fold-SD cutoff of Z-transformed sample connectivity. The Spearman rank correlation was performed prior to correction of cohort-specific batch effects as described above, and after intra-cohort batch correction of the MSSB and Banner cohorts. All four of the cohorts were confirmed to have no significant PC correlation to age, sex, or PMI; however, ACT was observed to have a first PC significantly correlated (average rho=0.94) to protein abundance of white matter markers identified previously as oligodendrocyte coexpression network hubs17. These markers were BCAS1, SIRT2, MBP, and MAG. This white matter PC represented 27 percent of variance in the ACT cohort, whereas the white matter marker-correlated PC represented 7 to 12 percent variance in the other three cohorts. To adjust for this white matter variance in ACT, we applied a second round of bootstrap regression to the 62 non-outlier ACT case sample log2(abundances), using the white matter PC as a regression covariate, and subtracted 28 percent of the white matter marker correlated variance to achieve a final variance of 12 percent after recalculation of the top 5 PCs. Abundance data for the 450 case samples were then assembled into a matrix of 3334 proteins, and cross-cohort batch correction by median polish was performed as described above. Finally, network outlier detection was performed as described above, which removed 31/450 cases from consideration in the four-cohort consensus network and differential abundance analyses. All outliers are listed in Supplementary Table 2. In all other cohorts that were not combined for the consensus network analysis, batch correction was performed first, followed by outlier removal, followed by removal of proteins with ≥ 50% missing values, and then regression of age, gender, and PMI prior to coexpression network and differential abundance analyses. In the Hopkins aging cohort, age was not considered as a trait for regression. In the CSF cohorts, only age at time of collection and sex were considered for regression.

Differential Expression Analysis

Differentially expressed proteins were found using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s comparison post-hoc test across control, AsymAD and AD cases. Significantly altered proteins with corresponding p value are provided in Supplementary Tables 2 and 5 for consensus AD network proteins and astrocyte/microglial phenotype proteins, respectively. Differential expression is presented as volcano plots, which were generated with the ggplot2 package in R v3.5.2.

Protein Correlations to Aging

Protein expression levels for all 2,756 proteins measured in the aging cohort with fewer than 50% missing values were correlated to age at death using the bicor function, after regression for sex and PMI. In addition to bicor rho, the Student’s p value for significance of the correlation, FDR (q value), and signed z score for the correlation were calculated. The CSGene database of cellular senescence genes71 was cross-referenced with the protein data to annotate proteins involved in cellular senescence. This information is provided in Supplementary Table 3, along with differences between AD, control, or AsymAD for the same proteins in the consensus network, and their corresponding consensus network module relationships. Individual correlations for proteins in the consensus network to all traits provided in Supplementary Figure 1 are provided online at https://www.synapse.org/consensus.

Weighted Correlation Network Analysis (WGCNA)