Hear “The Tell-Tale Heart” read aloud.

聆听大声朗读“告密的心”。

The Tell-Tale Heart 说谎的心

True! — nervous — very, very dreadfully nervous I had been and am; but why will you say that I am mad? The disease had sharpened my senses — not destroyed — not dulled them. Above all was the sense of hearing acute. I heard all things in the heaven and in the earth. I heard many things in hell. How, then, am I mad? Hearken! and observe how healthily — how calmly I can tell you the whole story.

真的! ——紧张——我过去和现在都非常非常紧张;但你为什么要说我生气呢?这种疾病使我的感觉更加敏锐——而不是被摧毁——更不是变得迟钝。最重要的是听觉敏锐。我听到了天上地下的一切。我在地狱里听到了很多事情。那我怎么生气了?倾听!并观察我如何健康地、如何平静地告诉你整个故事。

It is impossible to say how first the idea entered my brain; but once conceived, it haunted me day and night. Object there was none. Passion there was none. I loved the old man. He had never wronged me. He had never given me insult. For his gold I had no desire. I think it was his eye! yes, it was this! One of his eyes resembled that of a vulture — a pale blue eye, with a film over it. Whenever it fell upon me, my blood ran cold; and so by degrees — very gradually — I made up my mind to take the life of the old man, and thus rid myself of the eye forever.

无法说出这个想法是如何进入我的大脑的。但一旦怀孕,它就日夜困扰着我。没有对象。没有激情。我爱这个老人。他从来没有冤枉过我。他从来没有侮辱过我。对于他的金子我没有任何欲望。我想那是他的眼睛!是的,就是这个!他的一只眼睛就像秃鹰的眼睛——淡蓝色的眼睛,上面有一层薄膜。每当它落在我身上时,我的血液就会变冷;就这样,我渐渐地——慢慢地——下定决心要结束老人的生命,从而永远摆脱这只眼睛。

Now this is the point. You fancy me mad. Madmen know nothing. But you should have seen me. You should have seen how wisely I proceeded — with what caution — with what foresight — with what dissimulation I went to work! I was never kinder to the old man than during the whole week before I killed him. And every night, about midnight, I turned the latch of his door and opened it — oh, so gently! And then, when I had made an opening sufficient for my head, I put in a dark lantern, all closed, closed, so that no light shone out, and then I thrust in my head. Oh, you would have laughed to see how cunningly I thrust it in! I moved it slowly — very, very slowly, so that I might not disturb the old man’s sleep. It took me an hour to place my whole head within the opening so far that I could see him as he lay upon his bed. Ha! — would a madman have been so wise as this? And then, when my head was well in the room, I undid the lantern cautiously — oh, so cautiously — cautiously (for the hinges creaked) — I undid it just so much that a single thin ray fell upon the vulture eye. And this I did for seven long nights — every night just at midnight — but I found the eye always closed; and so it was impossible to do the work; for it was not the old man who vexed me, but his Evil Eye. And every morning, when the day broke, I went boldly into the chamber, and spoke courageously to him, calling him by name in a hearty tone, and inquiring how he had passed the night. So you see he would have been a very profound old man, indeed, to suspect that every night, just at twelve, I looked in upon him while he slept.

现在这就是重点。你想我生气了。疯子什么都不知道。但你应该见过我。你应该看到我是多么明智地——带着多么谨慎——带着多么远见——带着多么掩饰去工作!在我杀了他之前的整整一个星期里,我对这个老人从来没有像现在这样友善过。每天晚上,大约午夜,我转动他的门闩并打开它——哦,如此轻轻!然后,当我打开一个足以容纳我的头的开口时,我放入一盏黑暗的灯笼,所有的灯笼都关闭,关闭,这样就没有光照射出来,然后我把我的头插了进去。哦,如果你看到我把它插得多么巧妙,一定会笑的!我慢慢地移动它——非常非常慢,这样我就不会打扰老人的睡眠。我花了一个小时才将整个头放入开口中,直到他躺在床上时我才能看到他。哈! ——一个疯子会有这么聪明吗?然后,当我的头完全进入房间时,我小心翼翼地打开灯笼——哦,如此小心翼翼——小心翼翼(因为铰链吱吱作响)——我把它打开得太多了,以至于一束细细的光线落在秃鹰的眼睛上。我这样做了七个漫长的夜晚——每天晚上都在午夜——但我发现眼睛总是闭着的;所以这项工作不可能完成;因为让我烦恼的不是那个老人,而是他的邪眼。每天早上,天一亮,我就大胆地走进房间,勇敢地对他说话,用亲切的语气呼唤他的名字,询问他这一夜过得怎么样。所以你看,如果他怀疑每天晚上十二点的时候我在他睡觉的时候看着他,那他就是一个非常深刻的老人了。

Upon the eighth night I was more than usually cautious in opening the door. A watch’s minute hand moves more quickly than did mine. Never before that night had I felt the extent of my own powers — of my sagacity. I could scarcely contain my feelings of triumph. To think that there I was, opening the door, little by little, and he not even to dream of my secret deeds or thoughts. I fairly chuckled at the idea; and perhaps he heard me; for he moved on the bed suddenly, as if startled. Now you may think that I drew back — but no. His room was as black as pitch with the thick darkness, (for the shutters were close fastened, through fear of robbers,) and so I knew that he could not see the opening of the door, and I kept pushing it on steadily, steadily.

第八天晚上,我开门时比平时更加谨慎。手表的分针走得比我的快。那天晚上之前,我从未感受到自己的力量和智慧的程度。我几乎无法抑制自己的胜利感。想到我在那里,一点一点地打开门,而他甚至没有想到我的秘密行为或想法。我对这个想法嗤之以鼻。也许他听到了我的声音;因为他突然在床上动了动,仿佛受到了惊吓。现在你可能认为我退缩了——但事实并非如此。他的房间漆黑如漆,浓浓的黑暗(因为百叶窗紧闭,因为害怕强盗),所以我知道他看不到门的开口,所以我一直稳稳地推着门。 。

I had my head in, and was about to open the lantern, when my thumb slipped upon the tin fastening, and the old man sprang up in the bed, crying out — “Who’s there?”

我把头伸进去,正要打开灯笼,突然我的拇指滑到了锡扣上,老人从床上跳了起来,大声喊道:“谁在那儿?”

I kept quite still and said nothing. For a whole hour I did not move a muscle, and in the meantime I did not hear him lie down. He was still sitting up in the bed listening; — just as I have done, night after night, hearkening to the death watches in the wall.

我一动不动,什么也没说。整整一个小时,我一动不动,也没有听到他躺下的声音。他仍然坐在床上听着。 ——就像我所做的那样,夜复一夜,聆听墙上的死亡守望。

Presently I heard a slight groan, and I knew it was the groan of mortal terror. It was not a groan of pain or of grief — oh, no! — it was the low stifled sound that arises from the bottom of the soul when overcharged with awe. I knew the sound well. Many a night, just at midnight, when all the world slept, it has welled up from my own bosom, deepening, with its dreadful echo, the terrors that distracted me. I say I knew it well. I knew what the old man felt, and pitied him, although I chuckled at heart. I knew that he had been lying awake ever since the first slight noise, when he had turned in the bed. His fears had been ever since growing upon him. He had been trying to fancy them causeless, but could not. He had been saying to himself — “It is nothing but the wind in the chimney — it is only a mouse crossing the floor,” or “it is merely a cricket which has made a single chirp.” Yes, he has been trying to comfort himself with these suppositions: but he had found all in vain. All in vain; because Death, in approaching him had stalked with his black shadow before him, and enveloped the victim. And it was the mournful influence of the unperceived shadow that caused him to feel — although he neither saw nor heard — to feel the presence of my head within the room.

不久我听到一声轻微的呻吟,我知道那是致命恐惧的呻吟。这不是痛苦或悲伤的呻吟——哦,不! ——这是内心充满敬畏时从灵魂深处发出的低沉压抑的声音。我很熟悉这个声音。很多个夜晚,就在午夜时分,当全世界都入睡时,它就从我的怀里涌出,以其可怕的回声加深了令我心烦意乱的恐惧。我说我很了解。我知道老人的心情,也很可怜他,心里却笑了。我知道,自从他在床上翻身时,听到第一声轻微的响动,他就一直醒着。从那时起,他的恐惧就与日俱增。他一直试图无缘无故地幻想它们,但做不到。他一直对自己说:“不过是烟囱里的风而已,只是一只老鼠穿过地板”,或者“只是一只蟋蟀发出了一声鸣叫”。是的,他一直试图用这些假设来安慰自己:但他发现一切都是徒劳。一切都是徒劳;因为死神在逼近他的时候,就带着他的黑色影子在他面前悄悄逼近,将受害者包围起来。正是那个未被察觉的阴影所带来的悲伤影响,让他感觉到——尽管他既没有看到也没有听到——感觉到我的头在房间里的存在。

When I had waited a long time, very patiently, without hearing him lie down, I resolved to open a little — a very, very little crevice in the lantern. So I opened it — you cannot imagine how stealthily, stealthily — until, at length a single dim ray, like the thread of the spider, shot from out the crevice and fell upon the vulture eye.

当我非常耐心地等了很长一段时间,没有听到他躺下的声音时,我决定打开一点——灯笼上一个非常非常小的缝隙。于是我打开了它——你无法想象有多偷偷摸摸,偷偷摸摸——直到最后,一道暗淡的光线,像蜘蛛丝一样,从缝隙中射出,落在秃鹰的眼睛上。

It was open — wide, wide open — and I grew furious as I gazed upon it. I saw it with perfect distinctness — all a dull blue, with a hideous veil over it that chilled the very marrow in my bones; but I could see nothing else of the old man’s face or person: for I had directed the ray as if by instinct, precisely upon the damned spot.

它是敞开的——敞开的,敞开的——当我凝视它时,我变得愤怒起来。我看得非常清楚——全是暗蓝色,上面覆盖着一层可怕的面纱,让我的骨髓感到寒冷;但我看不到老人的脸或人:因为我仿佛本能地把光线精确地瞄准了那个该死的地方。

And now have I not told you that what you mistake for madness is but over acuteness of the senses? — now, I say, there came to my ears a low, dull, quick sound, such as a watch makes when enveloped in cotton. I knew that sound well, too. It was the beating of the old man’s heart. It increased my fury, as the beating of a drum stimulates the soldier into courage.

现在我不是告诉过你,你误认为疯狂只是因为感觉过于敏锐吗? ——现在,我说,我的耳朵里传来一种低沉、沉闷、急促的声音,就像手表被棉花包住时发出的声音一样。我也很熟悉这个声音。那是老人的心跳声。这增加了我的愤怒,因为鼓声刺激了士兵的勇气。

But even yet I refrained and kept still. I scarcely breathed. I held the lantern motionless. I tried how steadily I could maintain the ray upon the eye. Meantime the hellish tattoo of the heart increased. It grew quicker and quicker, and louder and louder every instant. The old man’s terror must have been extreme! It grew louder, I say, louder every moment! — do you mark me well? I have told you that I am nervous: so I am. And now at the dead hour of the night, amid the dreadful silence of that old house, so strange a noise as this excited me to uncontrollable terror. Yet, for some minutes longer I refrained and stood still. But the beating grew louder, louder! I thought the heart must burst. And now a new anxiety seized me — the sound would be heard by a neighbor! The old man’s hour had come! With a loud yell, I threw open the lantern and leaped into the room. He shrieked once — once only. In an instant I dragged him to the floor, and pulled the heavy bed over him. I then smiled gaily, to find the deed so far done. But, for many minutes, the heart beat on with a muffled sound. This, however, did not vex me; it would not be heard through the wall. At length it ceased. The old man was dead. I removed the bed and examined the corpse. Yes, he was stone, stone dead. I placed my hand upon the heart and held it there many minutes. There was no pulsation. He was stone dead. His eye would trouble me no more.

但即便如此,我还是忍住了,一动不动。我几乎没有呼吸。我拿着灯笼一动不动。我尝试着如何稳定地将光线保持在眼睛上。与此同时,心脏上的地狱纹身也增加了。它变得越来越快,声音越来越大。老者的恐怖,一定是到了极点!我说,它越来越响亮,每一刻都越来越响亮! ——你对我印象很好吗?我已经告诉过你我很紧张:我就是这样。现在,在夜深人静的时候,在那座老房子里可怕的寂静中,一种奇怪的声音让我兴奋得无法控制的恐惧。然而,又过了几分钟,我才忍住,一动不动地站着。但殴打的声音越来越大,越来越大!我想我的心一定要破裂。现在,一种新的焦虑占据了我——邻居会听到这个声音!老人的时刻到了!我大叫一声,扔开灯笼,跳进了房间。他尖叫了一次——仅一次。我立刻把他拖到地板上,拉过沉重的床压在他身上。然后我高兴地笑了,发现到目前为止的事情已经完成了。但是,有好几分钟,心脏一直在低沉地跳动。然而,这并没有让我烦恼。隔着墙都听不到声音。最后,它停了下来。老人死了。我移开床检查尸体。是的,他已经死了,死了。我把手放在心脏上并保持了很多分钟。没有脉动。他已经死了。他的眼睛不会再困扰我了。

If still you think me mad, you will think so no longer when I describe the wise precautions I took for the concealment of the body. The night waned, and I worked hastily, but in silence. First of all I dismembered the corpse. I cut off the head and the arms and the legs.

如果你还认为我疯了,当我描述我为隐藏尸体而采取的明智预防措施时,你就不会再这么想了。夜幕降临,我匆匆忙忙,却默默无闻。首先我肢解了尸体。我砍掉了头、胳膊和腿。

I then took up three planks from the flooring of the chamber, and deposited all between the scantlings. I then replaced the boards so cleverly, so cunningly, that no human eye — not even his — could have detected any thing wrong. There was nothing to wash out — no stain of any kind — no blood-spot whatever. I had been too wary for that. A tub had caught all — ha! ha!

然后我从房间的地板上拿起三块木板,并将所有木板放在尺寸之间。然后,我如此聪明、如此狡猾地更换了木板,以至于任何人的眼睛——甚至是他的眼睛——都无法发现任何错误。没有什么可以洗掉的——没有任何污渍——没有任何血迹。我对此太警惕了。一个浴缸把所有东西都盛了——哈!哈!

When I had made an end of these labors, it was four o ‘clock — still dark as midnight. As the bell sounded the hour, there came a knocking at the street door. I went down to open it with a light heart, — for what had I now to fear? There entered three men, who introduced themselves, with perfect suavity, as officers of the police. A shriek had been heard by a neighbor during the night; suspicion of foul play had been aroused; information had been lodged at the police office, and they (the officers) had been deputed to search the premises.

当我结束这些工作时,已是四点钟了——天色仍如午夜般漆黑。整点的钟声敲响时,临街的门响起了敲门声。我心情轻松地下去打开它——我现在还有什么好害怕的呢?进来了三个男人,他们非常温和地介绍自己,是警察。夜间,邻居听到一声尖叫;已引起谋杀嫌疑;信息已提交给警察局,他们(警官)已被派去搜查该处所。

I smiled, — for what had I to fear? I bade the gentlemen welcome. The shriek, I said, was my own in a dream. The old man, I mentioned, was absent in the country. I took my visitors all over the house. I bade them search — search well. I led them, at length, to his chamber. I showed them his treasures, secure, undisturbed. In the enthusiasm of my confidence, I brought chairs into the room, and desired them here to rest from their fatigues, while I myself, in the wild audacity of my perfect triumph, placed my own seat upon the very spot beneath which reposed the corpse of the victim.

我笑了:我有什么好害怕的?我向先生们表示欢迎。我说,那是我在梦中发出的尖叫声。我提到过,那位老人不在乡下。我带着客人参观了整个房子。我让他们搜查——好好搜查。我终于领着他们来到了他的房间。我向他们展示了他的宝藏,安全、不受干扰。怀着信心的热情,我把椅子搬进房间,希望他们在这里休息一下,消除疲劳,而我自己,在我的完美胜利的疯狂大胆中,把自己的座位放在尸体下面的地方。受害者的。

The officers were satisfied. My manner had convinced them. I was singularly at ease. They sat, and while I answered cheerily, they chatted of familiar things. But, ere long, I felt myself getting pale and wished them gone. My head ached, and I fancied a ringing in my ears: but still they sat and still chatted. The ringing became more distinct: — it continued and became more distinct: I talked more freely to get rid of the feeling: but it continued and gained definitiveness — until, at length, I found that the noise was not within my ears.

军官们很满意。我的态度说服了他们。我感到异常轻松。他们坐着,我高兴地回答,他们聊着熟悉的事情。但不久之后,我感觉自己的脸色变得苍白,希望它们消失。我的头很痛,我感觉耳朵里嗡嗡作响:但他们仍然坐着聊天。铃声变得更加清晰:——它继续,变得更加清晰:我更自由地说话,以摆脱这种感觉:但它继续并获得确定性——直到最后,我发现噪音不在我的耳朵里。

No doubt I now grew very pale; — but I talked more fluently, and with a heightened voice. Yet the sound increased — and what could I do? It was a low, dull, quick sound — much such a sound as a watch makes when enveloped in cotton. I gasped for breath — and yet the officers heard it not. I talked more quickly — more vehemently; but the noise steadily increased. I arose and argued about trifles, in a high key and with violent gesticulations; but the noise steadily increased. Why would they not be gone? I paced the floor to and fro with heavy strides, as if excited to fury by the observations of the men — but the noise steadily increased. Oh God! what could I do? I foamed — I raved — I swore! I swung the chair upon which I had been sitting, and grated it upon the boards, but the noise arose over all and continually increased. It grew louder — louder — louder! And still the men chatted pleasantly, and smiled. Was it possible they heard not? Almighty God! — no, no! They heard! — they suspected! — they knew! — they were making a mockery of my horror! — this I thought, and this I think. But anything was better than this agony! Anything was more tolerable than this derision! I could bear those hypocritical smiles no longer! I felt that I must scream or die! — and now — again! — hark! louder! louder! louder! louder! —

毫无疑问,我现在脸色变得非常苍白。 ——但我说话更流利了,声音也更高了。然而声音却越来越大——我能做什么呢?这是一种低沉、沉闷、急促的声音——就像手表被棉花包裹时发出的声音一样。我喘着粗气——但警官们却没有听到。我说话更快、更激烈;但噪音却逐渐增大。我站起来,就一些琐事争论起来,声音很高,手势也很粗暴。但噪音却逐渐增大。他们为什么不消失?我大步在地板上来回踱步,仿佛对这些人的观察感到兴奋到愤怒——但噪音逐渐增加。天啊!我能做什么?我口吐白沫——我大喊大叫——我发誓!我摇晃着我坐的椅子,把它放在木板上,但噪音却笼罩着一切,而且越来越大。声音越来越大——越来越大——越来越大!但男人们仍然愉快地聊天,面带微笑。他们有可能没有听到吗?全能神啊! ——不,不!他们听到了! ——他们怀疑! ——他们知道! ——他们在嘲笑我的恐惧! ——我是这样想的,我也是这样想的。但任何事情都比这种痛苦更好!还有什么比这种嘲笑更能忍受的了!我再也无法忍受那些虚伪的笑容了!我觉得我必须尖叫,否则就死! ——现在——又来了! ——听着!大声点!大声点!大声点!大声点! —

“Villains!” I shrieked, “dissemble no more! I admit the deed! — tear up the planks! — here, here! — it is the beating of his hideous heart!”

“恶棍!”我尖叫道:“别再说了!我承认这个行为! ——撕碎木板! ——这里,这里! ——这是他那可怕的心脏的跳动!”

Edgar Allan Poe 埃德加·爱伦·坡

January 1843 1843 年 1 月

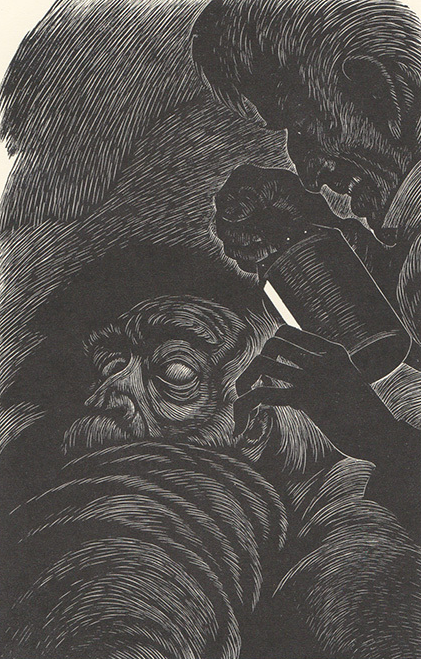

Illustration by Harry Clarke

哈里·克拉克的插图