Editor’s note: 编者注:

Today, more of the world’s population is bilingual or multilingual than monolingual. In addition to facilitating cross-cultural communication, this trend also positively affects cognitive abilities. Researchers have shown that the bilingual brain can have better attention and task-switching capacities than the monolingual brain, thanks to its developed ability to inhibit one language while using another. In addition, bilingualism has positive effects at both ends of the age spectrum: Bilingual children as young as seven months can better adjust to environmental changes, while bilingual seniors can experience less cognitive decline.

如今,世界上双语或多语人口多于单语人口。除了促进跨文化交流之外,这种趋势还对认知能力产生积极影响。研究人员表明,双语大脑比单语大脑具有更好的注意力和任务切换能力,这要归功于双语大脑在使用另一种语言时抑制一种语言的能力。此外,双语对年龄段的两端都有积极影响:七个月大的双语儿童可以更好地适应环境变化,而双语老年人可以经历较少的认知衰退。

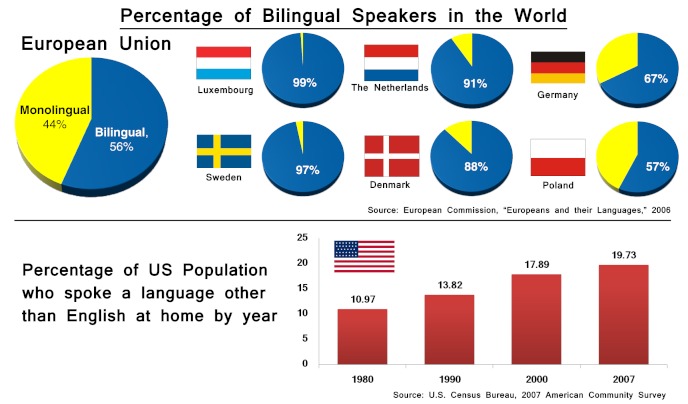

We are surrounded by language during nearly every waking moment of our lives. We use language to communicate our thoughts and feelings, to connect with others and identify with our culture, and to understand the world around us. And for many people, this rich linguistic environment involves not just one language but two or more. In fact, the majority of the world’s population is bilingual or multilingual. In a survey conducted by the European Commission in 2006, 56 percent of respondents reported being able to speak in a language other than their mother tongue. In many countries that percentage is even higher—for instance, 99 percent of Luxembourgers and 95 percent of Latvians speak more than one language.1 Even in the United States, which is widely considered to be monolingual, one-fifth of those over the age of five reported speaking a language other than English at home in 2007, an increase of 140 percent since 1980.2 Millions of Americans use a language other than English in their everyday lives outside of the home, when they are at work or in the classroom. Europe and the United States are not alone, either. The Associated Press reports that up to 66 percent of the world’s children are raised bilingual.3 Over the past few decades, technological advances have allowed researchers to peer deeper into the brain to investigate how bilingualism interacts with and changes the cognitive and neurological systems.

在我们生命中几乎每一个醒着的时刻,我们都被语言包围着。我们使用语言来交流我们的想法和感受,与他人联系并认同我们的文化,并了解我们周围的世界。对于许多人来说,这种丰富的语言环境不仅涉及一种语言,而且涉及两种或多种语言。事实上,世界上大多数人口都会说双语或多语。欧盟委员会 2006 年进行的一项调查显示,56% 的受访者表示能够使用母语以外的语言进行交流。在许多国家,这一比例甚至更高,例如,99% 的卢森堡人和 95% 的拉脱维亚人会说不止一种语言。 1 即使在被广泛认为是单语国家的美国,2007 年五分之一的五岁以上人口也表示在家中说英语以外的语言,这一数字自 1980 年以来增加了 140%。 2 数以百万计的美国人在日常生活中、工作中或课堂上使用英语以外的语言。欧洲和美国也不孤单。据美联社报道,世界上高达 66% 的儿童是在双语环境下长大的。 3 在过去的几十年里,技术进步使研究人员能够更深入地观察大脑,以研究双语如何与认知和神经系统相互作用并改变它们。

Cognitive Consequences of Bilingualism

双语的认知后果

Research has overwhelmingly shown that when a bilingual person uses one language, the other is active at the same time. When a person hears a word, he or she doesn’t hear the entire word all at once: the sounds arrive in sequential order. Long before the word is finished, the brain’s language system begins to guess what that word might be by activating lots of words that match the signal. If you hear “can,” you will likely activate words like “candy” and “candle” as well, at least during the earlier stages of word recognition. For bilingual people, this activation is not limited to a single language; auditory input activates corresponding words regardless of the language to which they belong.4

研究绝大多数表明,当双语者使用一种语言时,另一种语言也会同时活跃。当一个人听到一个单词时,他或她不会立即听到整个单词:声音按顺序到达。早在单词完成之前,大脑的语言系统就开始通过激活大量与信号匹配的单词来猜测该单词可能是什么。如果您听到“can”,您可能也会激活“candy”和“candle”等单词,至少在单词识别的早期阶段是这样。对于双语者来说,这种激活不仅限于单一语言;听觉输入会激活相应的单词,无论它们属于哪种语言。 4

Some of the most compelling evidence for language co-activation comes from studying eye movements. We tend to look at things that we are thinking, talking, or hearing about.5 A Russian-English bilingual person asked to “pick up a marker” from a set of objects would look more at a stamp than someone who doesn’t know Russian, because the Russian word for “stamp,” “marka,” sounds like the English word he or she heard, “marker.”4 In cases like this, language co-activation occurs because what the listener hears could map onto words in either language. Furthermore, language co-activation is so automatic that people consider words in both languages even without overt similarity. For example, when Chinese-English bilingual people judge how alike two English words are in meaning, their brain responses are affected by whether or not the Chinese translations of those words are written similarly.6 Even though the task does not require the bilingual people to engage their Chinese, they do so anyway.

语言共同激活的一些最令人信服的证据来自对眼球运动的研究。我们倾向于关注我们正在思考、谈论或听到的事物。 5 一个俄英双语者被要求从一组物体中“拿起一个标记”时,他会比不懂俄语的人更多地看邮票,因为俄语中“邮票”的单词“ marka ”听起来像他或她听到的英语单词是“标记”。 4 在这种情况下,会发生语言共激活,因为听者听到的内容可以映射到任一语言的单词上。此外,语言共同激活是如此自动,以至于人们即使没有明显的相似性也会考虑两种语言中的单词。例如,当中英双语者判断两个英文单词的含义有多相似时,他们的大脑反应会受到这些单词的中文翻译是否相似的影响。 6 尽管这项任务并不要求双语者使用中文,但他们还是这么做了。

Having to deal with this persistent linguistic competition can result in language difficulties. For instance, knowing more than one language can cause speakers to name pictures more slowly7 and can increase tip-of-the-tongue states (where you’re unable to fully conjure a word, but can remember specific details about it, like what letter it starts with).8 As a result, the constant juggling of two languages creates a need to control how much a person accesses a language at any given time. From a communicative standpoint, this is an important skill—understanding a message in one language can be difficult if your other language always interferes. Likewise, if a bilingual person frequently switches between languages when speaking, it can confuse the listener, especially if that listener knows only one of the speaker’s languages.

必须应对这种持续的语言竞争可能会导致语言困难。例如,了解一种以上语言可能会导致说话者命名图片的速度变慢 7 并且可以增加舌尖状态(你无法完全想象出一个单词,但可以记住它的具体细节,比如它以哪个字母开头)。 8 因此,两种语言的不断混合产生了控制一个人在任何给定时间访问一种语言的程度的需要。从交流的角度来看,这是一项重要的技能——如果另一种语言总是干扰,那么理解一种语言的消息可能会很困难。同样,如果双语者在说话时频繁地在语言之间切换,可能会让听者感到困惑,特别是当听者只知道说话者的一种语言时。

To maintain the relative balance between two languages, the bilingual brain relies on executive functions, a regulatory system of general cognitive abilities that includes processes such as attention and inhibition. Because both of a bilingual person’s language systems are always active and competing, that person uses these control mechanisms every time she or he speaks or listens. This constant practice strengthens the control mechanisms and changes the associated brain regions.9–12

为了维持两种语言之间的相对平衡,双语大脑依赖于执行功能,这是一种一般认知能力的调节系统,包括注意力和抑制等过程。因为双语者的两种语言系统总是活跃且相互竞争的,所以该人每次说话或听时都会使用这些控制机制。这种不断的练习可以增强控制机制并改变相关的大脑区域。 9 – 12

Bilingual people often perform better on tasks that require conflict management. In the classic Stroop task, people see a word and are asked to name the color of the word’s font. When the color and the word match (i.e., the word “red” printed in red), people correctly name the color more quickly than when the color and the word don’t match (i.e., the word “red” printed in blue). This occurs because the word itself (“red”) and its font color (blue) conflict. The cognitive system must employ additional resources to ignore the irrelevant word and focus on the relevant color. The ability to ignore competing perceptual information and focus on the relevant aspects of the input is called inhibitory control. Bilingual people often perform better than monolingual people at tasks that tap into inhibitory control ability. Bilingual people are also better than monolingual people at switching between two tasks; for example, when bilinguals have to switch from categorizing objects by color (red or green) to categorizing them by shape (circle or triangle), they do so more rapidly than monolingual people,13 reflecting better cognitive control when changing strategies on the fly.

双语者通常在需要冲突管理的任务上表现更好。在经典中 Stroop task ,人们看到一个单词,并被要求说出该单词字体的颜色。当颜色和单词匹配时(即,单词“红色”打印为红色),人们比颜色和单词不匹配时(即单词“红色”打印为蓝色)更快地正确命名颜色。发生这种情况是因为单词本身(“红色”)与其字体颜色(蓝色)冲突。认知系统必须使用额外的资源来忽略不相关的单词并专注于相关的颜色。忽略竞争性感知信息并专注于输入的相关方面的能力称为抑制控制。在涉及抑制控制能力的任务中,双语者通常比单语者表现得更好。双语者在两项任务之间的切换方面也比单语者更好。例如,当双语者必须从按颜色(红色或绿色)对物体进行分类切换到按形状(圆形或三角形)对物体进行分类时,他们比单语者做得更快, 13 反映在动态改变策略时更好的认知控制。

Changes in Neurological Processing and Structure

Studies suggest that bilingual advantages in executive function are not limited to the brain’s language networks.9 Researchers have used brain imaging techniques like functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) to investigate which brain regions are active when bilingual people perform tasks in which they are forced to alternate between their two languages. For instance, when bilingual people have to switch between naming pictures in Spanish and naming them in English, they show increased activation in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC), a brain region associated with cognitive skills like attention and inhibition.14 Along with the DLPFC, language switching has been found to involve such structures as the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC), bilateral supermarginal gyri, and left inferior frontal gyrus (left-IFG), regions that are also involved in cognitive control.9 The left-IFG in particular, often considered the language production center of the brain, appears to be involved in both linguistic15 and non-linguistic cognitive control.16

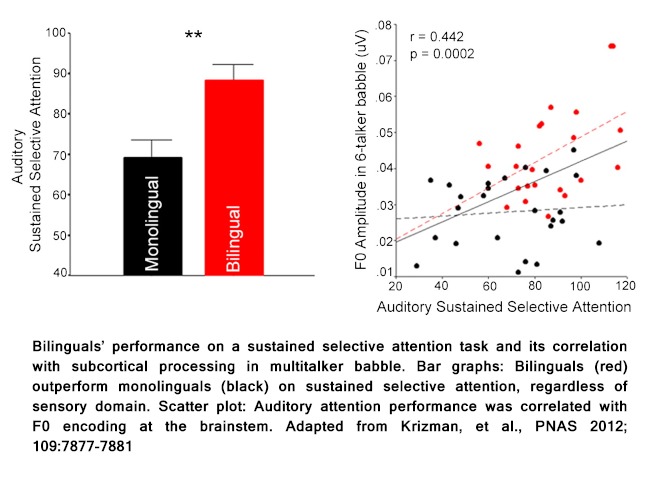

The neurological roots of the bilingual advantage extend to subcortical brain areas more traditionally associated with sensory processing. When monolingual and bilingual adolescents listen to simple speech sounds (e.g., the syllable “da”) without any intervening background noise, they show highly similar brain stem responses to the auditory information. When researchers play the same sound to both groups in the presence of background noise, the bilingual listeners’ neural response is considerably larger, reflecting better encoding of the sound’s fundamental frequency,17 a feature of sound closely related to pitch perception. To put it another way, in bilingual people, blood flow (a marker for neuronal activity) is greater in the brain stem in response to the sound. Intriguingly, this boost in sound encoding appears to be related to advantages in auditory attention. The cognitive control required to manage multiple languages appears to have broad effects on neurological function, fine-tuning both cognitive control mechanisms and sensory processes.

Beyond differences in neuronal activation, bilingualism seems to affect the brain’s structure as well. Higher proficiency in a second language, as well as earlier acquisition of that language, correlates with higher gray matter volume in the left inferior parietal cortex.18 Researchers have associated damage to this area with uncontrolled language switching,19 suggesting that it may play an important role in managing the balance between two languages. Likewise, researchers have found white matter volume changes in bilingual children20 and older adults.21 It appears that bilingual experience not only changes the way neurological structures process information, but also may alter the neurological structures themselves.

Improvements in Learning

Being bilingual can have tangible practical benefits. The improvements in cognitive and sensory processing driven by bilingual experience may help a bilingual person to better process information in the environment, leading to a clearer signal for learning. This kind of improved attention to detail may help explain why bilingual adults learn a third language better than monolingual adults learn a second language.22 The bilingual language-learning advantage may be rooted in the ability to focus on information about the new language while reducing interference from the languages they already know.23 This ability would allow bilingual people to more easily access newly learned words, leading to larger gains in vocabulary than those experienced by monolingual people who aren’t as skilled at inhibiting competing information.

Furthermore, the benefits associated with bilingual experience seem to start quite early—researchers have shown bilingualism to positively influence attention and conflict management in infants as young as seven months. In one study, researchers taught babies growing up in monolingual or bilingual homes that when they heard a tinkling sound, a puppet appeared on one side of a screen. Halfway through the study, the puppet began appearing on the opposite side of the screen. In order to get a reward, the infants had to adjust the rule they’d learned; only the bilingual babies were able to successfully learn the new rule.24 This suggests that even for very young children, navigating a multilingual environment imparts advantages that transfer beyond language.

Protecting Against Age-Related Decline

The cognitive and neurological benefits of bilingualism also extend into older adulthood. Bilingualism appears to provide a means of fending off a natural decline of cognitive function and maintaining what is called “cognitive reserve.”9, 25 Cognitive reserve refers to the efficient utilization of brain networks to enhance brain function during aging. Bilingual experience may contribute to this reserve by keeping the cognitive mechanisms sharp and helping to recruit alternate brain networks to compensate for those that become damaged during aging. Older bilingual people enjoy improved memory26 and executive control9 relative to older monolingual people, which can lead to real-world health benefits.

In addition to staving off the decline that often comes with aging, bilingualism can also protect against illnesses that hasten this decline, like Alzheimer’s disease. In a study of more than 200 bilingual and monolingual patients with Alzheimer’s disease, bilingual patients reported showing initial symptoms of the disease at about 77.7 years of age—5.1 years later than the monolingual average of 72.6. Likewise, bilingual patients were diagnosed 4.3 years later than the monolingual patients (80.8 years of age and 76.5 years of age, respectively).25 In a follow-up study, researchers compared the brains of bilingual and monolingual patients matched on the severity of Alzheimer’s symptoms. Surprisingly, the brains of bilingual people showed a significantly higher degree of physical atrophy in regions commonly associated with Alzheimer’s disease.27 In other words, the bilingual people had more physical signs of disease than their monolingual counterparts, yet performed on par behaviorally, even though their degree of brain atrophy suggested that their symptoms should be much worse. If the brain is an engine, bilingualism may help to improve its mileage, allowing it to go farther on the same amount of fuel.

Conclusion

The cognitive and neurological benefits of bilingualism extend from early childhood to old age as the brain more efficiently processes information and staves off cognitive decline. What’s more, the attention and aging benefits discussed above aren’t exclusive to people who were raised bilingual; they are also seen in people who learn a second language later in life.25, 28 The enriched cognitive control that comes along with bilingual experience represents just one of the advantages that bilingual people enjoy. Despite certain linguistic limitations that have been observed in bilinguals (e.g., increased naming difficulty7), bilingualism has been associated with improved metalinguistic awareness (the ability to recognize language as a system that can be manipulated and explored), as well as with better memory, visual-spatial skills, and even creativity.29 Furthermore, beyond these cognitive and neurological advantages, there are also valuable social benefits that come from being bilingual, among them the ability to explore a culture through its native tongue or talk to someone with whom you might otherwise never be able to communicate. The cognitive, neural, and social advantages observed in bilingual people highlight the need to consider how bilingualism shapes the activity and the architecture of the brain, and ultimately how language is represented in the human mind, especially since the majority of speakers in the world experience life through more than one language.

Footnotes

Article available online at http://www.dana.org/news/cerebrum/detail.aspx?id=39638

References

- 1.European Commission Special Eurobarometer Europeans and their languages. 2006. Retrieved October 1, 2012, from http://ec.europa.eu/public_opinion/archives/ebs/ebs_243_en.pdf.

- 2.United States Census Bureau American Community Survey. Retrieved October 1, 2012, from http://www.census.gov/acs/www/

- 3.Associated Press Some facts about the world’s 6,800 tongues. 2001. Retrieved October 1, 2012, from http://articles.cnn.com/2001-06-19/us/language.glance_1_languages-origin-tongues?_s=PM:US.

- 4.Marian V, Spivey M. Bilingual and monolingual processing of competing lexical items. Applied Psycholinguistics. 2003;24(2):173–193. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tanenhaus MK, Magnuson JS, Dahan D, Chambers C. Eye movements and lexical access in spoken-language comprehension: Evaluating a linking hypothesis between fixations and linguistic processing. Journal of Psycholinguistic Research. 2000;29(6):557–580. doi: 10.1023/a:1026464108329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thierry G, Wu YJ. Brain potentials reveal unconscious translation during foreign-language comprehension. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2007;104(30):12530–12535. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0609927104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gollan TH, Montoya RI, Fennema-Notestine C, Morris SK. Bilingualism affects picture naming but not picture classification. Memory and Cognition. 2005;33(7):1220–1234. doi: 10.3758/bf03193224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gollan TH, Acenas LA. What is a TOT? Cognate and translation effects on tip-of-the-tongue states in Spanish-English and Tagalog-English bilinguals. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition. 2004;301246:269. doi: 10.1037/0278-7393.30.1.246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bialystok E, Craik FI, Luk G. Bilingualism: Consequences for mind and brain. Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 2012;16(4):240–250. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2012.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Abutalebi J, Annoni J-M, Zimine I, Pegna AJ, Segheir ML, Lee-Jahnke H, Lazeyras F, Cappa SF, Khateb A. Language control and lexical competition in bilinguals: An event-related fMRI study. Cerebral Cortex. 2008;18(7):1496–1505. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhm182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Abutalebi J, Pasquale ADR, Green DW, Hernandez M, Scifo P, Keim R, Cappa SF, Costa A. Bilingualism tunes the anterior cingulate cortex for conflict monitoring. Cerebral Cortex. 2011 doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhr287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Green DW. Bilingual worlds. In: Cook V, Bassetti B, editors. Language and bilingual cognition. New York: Psychology Press; 2011. pp. 229–240. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Prior A, MacWhinney B. A bilingual advantage in task switching. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition. 2010;13(2):253–262. doi: 10.1017/S1366728909990526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hernandez AE, Martinez A, Kohnert K. In search of the language switch: An fMRI study of picture naming in Spanish-English bilinguals. Brain and Language. 2000;73(3):421–431. doi: 10.1006/brln.1999.2278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Abutalebi J, Green DW. Control mechanisms in bilingual language production: Neural evidence from language switching studies. Language and Cognitive Processes. 2008;23(4):557–582. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Garbin G, Sanjuan A, Forn C, Bustamante JC, Rodriguez-Pujadas A, Belloch V, Avila C. Bridging language and attention: Brain basis of the impact of bilingualism on cognitive control. NeuroImage. 2010;53(4):1272–1278. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.05.078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Krizman J, Marian V, Shook A, Skoe E, Kraus N. Subcortical encoding of sound is enhanced in bilinguals and relates to executive function advantages. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2012;109(20):7877–7881. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1201575109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mechelli A, Crinion JT, Noppeney U, O’Doherty J, Ashburner J, Frackowiak RS, Price CJ. Neurolinguistics: Structural plasticity in the bilingual brain. Nature. 2004;431(7010):757. doi: 10.1038/431757a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fabbro F, Skrap M, Aglioti S. Pathological switching between languages after frontal lesions in a bilingual patient. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry. 2000;68(5):650–652. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.68.5.650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mohades SG, Struys E, Van Schuerbeek P, Mondt K, Van De Craen P, Luypaert R. DTI reveals structural differences in white matter tracts between bilingual and monolingual children. Brain Research. 2012;1435(72):80. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2011.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Luk G, Bialystok E, Craik FI, Grady CL. Lifelong bilingualism maintains white matter integrity in older adults. Journal of Neuroscience. 2011;31(46):16808–16813. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4563-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kaushanskaya M, Marian V. The bilingual advantage in novel word learning. Psychonomic Bulletin and Review. 2009;16(4):705–710. doi: 10.3758/PBR.16.4.705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bartolotti J, Marian V. Language learning and control in monolinguals and bilinguals. Cognitive Science. 2012;36(1129):1147. doi: 10.1111/j.1551-6709.2012.01243.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kovacs AM, Mehler J. Cognitive gains in 7-month-old bilingual infants. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2009;106(16):6556–6560. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0811323106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Craik FI, Bialystok E, Freedman M. Delaying the onset of Alzheimer disease: Bilingualism as a form of cognitive reserve. Neurology. 2010;75(19):1726–1729. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181fc2a1c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schroeder SR, Marian V. A bilingual advantage for episodic memory in older adults. Journal of Cognitive Psychology. 2012;24(5):591–601. doi: 10.1080/20445911.2012.669367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schweizer TA, Ware J, Fischer CE, Craik FI, Bialystok E. Bilingualism as a contributor to cognitive reserve: Evidence from brain atrophy in Alzheimer’s disease. Cortex. 2012;48(8):991–996. doi: 10.1016/j.cortex.2011.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Linck JA, Hoshino N, Kroll JF. Cross-language lexical processes and inhibitory control. Mental Lexicon. 2008;3(3):349–374. doi: 10.1075/ml.3.3.06lin. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Diaz R, Klingler C. Towards an explanatory model of the interaction between bilingualism and cognitive development. In: Bialystok E, editor. Language processing in bilingual children. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1991. pp. 167–192. [Google Scholar]