Abstract

Leptin is a hormone produced from adipose tissue, targeting the hypothalamus and regulating energy expenditure, adipose tissue mass, and reproductive function. Leptin concentration reflects body weight and the amount of energy stored, as well as the level of reproductive hormones and male fertility. In this review, the aim was to focus on leptin signaling mechanisms and the significant influence of leptin on the male reproductive system and to summarize the current knowledge of clinical and experimental studies. The PubMed database was searched for studies on leptin and the male reproductive system to summarize the mechanism of leptin in the male reproductive system. Studies have shown that obesity-related, high leptin levels or leptin resistance negatively affects male reproductive functions. Leptin directly affects the testis by binding to the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis and the receptors of testicular cells, and thus the location of leptin receptors plays a key role in the regulation of the male reproductive system with the negative feedback mechanism between adipose tissue and hypothalamus. Based on the current evidence, leptin may totally inhibit male reproduction, and investigation of this role of leptin has established a potential interaction between obesity and male infertility. The mechanism of leptin in the male reproductive system should be further investigated and possible treatments for subfertility should be evaluated, supported by better understanding of leptin and associated signaling mechanisms.

Keywords: Leptin, male reproductive system, obesity

Introduction

Leptin is a hormone largely produced by adipocytes (1). Leptin receptors are widely spread in many tissues, cells, and endocrine glands and perform vital functions by binding to leptin and activating several pathways including Janus kinase/signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (JAK/STAT3), extracellular signal-regulated kinases 1/2 (ERK 1/2), and phosphoinositide 3-kinases (PI3K)/AKT signal pathways (2, 3). Leptin receptors are particularly concentrated in the hypothalamus, and by binding to them, leptin stimulates neuronal pathways that control body weight and energy expenditure and stimulate the pituitary gland to release gonadotropin hormones. Gonadotropin hormones play a crucial role in regulating the timing of puberty and reproductive functions, which means that leptin plays a role in regulating fertility and body weight simultaneously and across common pathways (4, 5). Leptin levels correlate positively with fat mass. Excess body weight and obesity lead to increased secretion of leptin, and this usually causes resistance to leptin (6, 7). Moreover, low body weight leads to a lack of leptin, and therefore it is normal for reproductive function disorders in obese or thin men to be caused by excess, deficiency, or resistance to leptin (8). Leptin resistance is not only related to obesity, but may also result from a genetic defect in leptin receptors, and variants may occur in the leptin gene (ob) that lead to the failure to produce leptin (9, 10). In addition, leptin plays a role independent of the hypothalamus in regulating testicular functions and steroidogenesis through its association with its receptors throughout all testicular and sperm cells (11, 12). Leptin is also involved in the negative effects of some diseases on reproductive functions (13, 14). In this review, we aim to summarize the role of the physiological leptin in reproductive function, the relationship between leptin level and fertility, and the risk of subfertility.

Leptin

Leptin is a protein hormone produced from white adipose tissue by the Ob gene. Like many other hormones, leptin is secreted in a pulsatile fashion at higher levels in the evening and early morning hours (15). It is released into the bloodstream and binds to its receptors in the hypothalamus, creating a feeling of satiety, and therefore it was previously called the “satiety hormone” (1, 16, 17). Leptin maintains its functions by binding to specific leptin receptors (Ob-Rs) expressed in peripheral tissues, as well as in the brain. There are several isoforms of Ob-Rs. The Ob-Ra isoform (short leptin receptor isoform) plays an important role in the transport of leptin across the blood-brain barrier (BBB) (18). The Ob-Rb isoform (long leptin receptor isoform) is strongly expressed and mediates signal transduction in the hypothalamus, a region important for the regulation of neuroendocrine and energy homeostasis (19, 20). Leptin is also secreted in small quantities from gastric mucosa, brown adipose tissue, bone marrow, striated muscle cells, mammary gland, ovaries, brain tissue, lymph tissue, placenta, and spermatozoa (21, 22, 23). Leptin regulates its vital functions by binding to ob-Rs, which are found on neuronal and non-neuronal cells. The most important roles of leptin are to regulate fat storage, energy consumption, neuroendocrine function, immunity, reproduction, bone metabolism, angiogenesis, inflammation, growth hormone secretion, and improvement in insulin sensitivity (24, 25, 26).

Leptin receptors

Leptin receptors are divided into six types, one of them is long (ob-Rb), four short (ob-Ra, ob-Rc, ob-Rd, ob-Rf), and one soluble (ob-Re), according to the length of their domains inside the cell (27). The long, active isoform of Ob-Rb is expressed primarily in the hypothalamus, and plays an important role in the regulation of endocrine organs and energy homeostasis. Also, it has been reported that leptin receptors located in the uterine artery during the ovarian cycle and pregnancy regulate angiogenesis in uterine artery endothelial cells (28). Ob-Rb is found in all immune cells related to adaptive and innate immunity (29, 30, 31). Another study demonstrated that leptin/ob-Rb signaling plays an important role in the pathogenesis of obesity-associated neutrophilic airway inflammation in women by promoting M1 macrophage polarization (32). Lack of full-length Ob-Rb receptor in obese rats and db/db mice induces the development of early obesity phenotype. In db/db mice, the presence of a short Ob-Ra isoform with limited activity causes morbid obesity, diabetes, and developmental disorders in adolescence. Furthermore, the db/db mouse phenotype lacks leptin receptors but exhibits a significantly higher blood leptin concentration (33). The cytoplasmic domains of the long receptor contain segments capable of activating the JAK-STAT3 pathway and are found largely in the hypothalamus, and in small amounts in the lungs, pancreas, muscles, ovaries, testes, blood, kidney, heart, BBB, and sperm (2, 4). The cytoplasmic domains of the short receptor lack the segments that activate the JAK/STAT3 pathway, but it can activate leptin signals via the adenosine monophosphate kinase (AMPK) pathways, and it is found in the liver, pancreas, gonad, and BBB (4, 34). The soluble receptor lacks both cytoplasmic and membrane segments and plays a role as a leptin-binding protein in blood circulation and regulates its bioavailability and is also found in the seminal plasma (35, 36). The majority of Ob-R isoform receptors are intracellular, with only 5-25% found on the cell surface. After ligand binding, the receptors are internalized into endosomes via clathrin-coated vesicles. The receptor is broken down or recycled to the cell membrane. A decrease in Ob-Rb expression is much greater than changes in Ob-Ra expression, and the short isoform Ob-Ra is recycled much more rapidly to the cell membrane (37, 38, 39).

瘦素受体根据它们在细胞内的结构域的长度分为六种类型,其中一种是长的 (ob-Rb),四种是短的 (ob-Ra, ob-Rc, ob-Rd, ob-Rf),一种是可溶的 (ob-Re 27 )。Ob-Rb 的长活性亚型主要在下丘脑中表达,在内分泌器官的调节和能量稳态中起重要作用。此外,据报道,在卵巢周期和怀孕期间,位于子宫动脉中的瘦素受体调节子宫动脉内皮细胞的血管生成 ( 28 )。Ob-Rb 存在于与适应性免疫和先天免疫相关的所有免疫细胞中 ( 29 , 30 , 31 )。另一项研究表明,瘦素/ob-Rb 信号转导通过促进 M1 巨噬细胞极化,在女性肥胖相关中性粒细胞气道炎症的发病机制中起重要作用 ( 32 )。肥胖大鼠和 db/db 小鼠缺乏全长 Ob-Rb 受体会诱导早期肥胖表型的发展。在 db/db 小鼠中,存在活性有限的短 Ob-Ra 亚型会导致青春期病态肥胖、糖尿病和发育障碍。此外,db/db 小鼠表型缺乏瘦素受体,但表现出显著较高的血液瘦素浓度 ( 33 )。长受体的细胞质结构域包含能够激活 JAK-STAT3 通路的片段,主要存在于下丘脑中,少量存在于肺、胰腺、肌肉、卵巢、睾丸、血液、肾脏、心脏、BBB 和精子中 ( 2 , 4 )。 短受体的胞质结构域缺乏激活 JAK/STAT3 通路的片段,但它可以通过单磷酸腺苷激酶 (AMPK) 通路激活瘦素信号,存在于肝脏、胰腺、性腺和 BBB ( 4 , 34 )。可溶性受体缺乏细胞质片段和膜片段,在血液循环中作为瘦素结合蛋白发挥作用并调节其生物利用度,也存在于精浆中 ( 35 , 36 )。大多数 Ob-R 亚型受体位于细胞内,只有 5-25% 存在于细胞表面。配体结合后,受体通过网格蛋白包被的囊泡内化到内体中。受体被分解或循环到细胞膜上。Ob-Rb 表达的降低远大于 Ob-Ra 表达的变化,并且短亚型 Ob-Ra 循环到细胞膜的速度要快得多 ( 37 、 、 38 39 )。

Leptin signaling pathways

瘦素信号通路

Leptin causes JAK/STAT3 signal activation by binding to long receptors (ob-Rb) with intracellular signaling capabilities. JAK2 phosphorylates Tyr985, Tyr1138, and Tyr1077 tyrosine localize in the intracellular domain. Two units of STAT3 bind to phosphorylated tyrosine residues and are phosphorylated to form the STAT3 dimer. The dimer migrates to the nucleus and binds to target genes. If this signal occurs in the hypothalamus, the dimer activates cocaine- and amphetamine-regulated transcript (CART) and pro-opiomelanocortin (POMC) neurons and inhibits agouti-related peptide (AGRP) and neuropeptide Y (NPY) neurons. Moreover, the dimer causes transcription of suppressors of cytokine signaling 3 (SOCS3) which prevents excessive activation of leptin by inhibiting JAK2, so this protein is part of the negative feedback mechanism (35, 40).

瘦素通过与具有细胞内信号传导能力的长受体 (ob-Rb) 结合来引起 JAK/STAT3 信号激活。JAK2 磷酸化 Tyr985、Tyr1138 和 Tyr1077 酪氨酸位于细胞内结构域中。两个单元的 STAT3 与磷酸化的酪氨酸残基结合,并被磷酸化形成 STAT3 二聚体。二聚体迁移到细胞核并与靶基因结合。如果该信号发生在下丘脑,二聚体会激活可卡因和苯丙胺调节转录物 (CART) 和促阿片黑皮质素 (POMC) 神经元,并抑制刺豚鼠相关肽 (AGRP) 和神经肽 Y (NPY) 神经元。此外,二聚体引起细胞因子信号转导 3 (SOCS3) 抑制因子的转录,从而通过抑制 JAK2 来防止瘦素的过度激活,因此该蛋白是负反馈机制的一部分 ( 35 , 40 )。

When leptin binds to the receptor, a second signal pathway, ERK1/2 [also known as Ras/Raf/mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK)], is also activated. Tyrosine-protein phosfatase (SHP2) and growth factor receptor-bound protein 2 bind to Tyr985 residue phosphorylated by JAK2. Then the enzyme, ERK, initiates a protein chain. Afterward, the activated mammalian target of rapamycin complex 1 (mTORC1) inhibits the AMPK signal. ERK also activates MAPK (3, 40). AMPK enzyme functions as an energy sensor. When the energy level inside the cell decreases and the ATP ratio increases, AMPK is activated by phosphorylation of the α subunit, allowing amino acids and glucose to enter the cell for energy synthesis. Thus, leptin must inhibit this enzyme to secure energy consumption (41, 42). AMPK is also found in the midpiece and flagellum of the sperm and plays a role in motility modulation. Therefore, in the absence of leptin expression or if mTORC1 is deleted, AMPK is not inhibited, resulting in decreased sperm motility (43).

当瘦素与受体结合时,第二个信号通路 ERK1/2 [也称为 Ras/Raf/丝裂原活化蛋白激酶 (MAPK)] 也被激活。酪氨酸蛋白磷酸酶 (SHP2) 和生长因子受体结合蛋白 2 与被 JAK2 磷酸化的 Tyr985 残基结合。然后 ERK 酶启动一条蛋白质链。之后,雷帕霉素复合物 1 (mTORC1) 的激活哺乳动物靶标抑制 AMPK 信号。ERK 还会激活 MAPK ( 3 , 40 )。AMPK 酶起能量传感器的作用。当细胞内的能量水平降低而 ATP 比率增加时,AMPK 被 α 亚基磷酸化激活,使氨基酸和葡萄糖进入细胞进行能量合成。因此,瘦素必须抑制这种酶以确保能量消耗 ( 41 , 42 )。AMPK 也存在于精子的中段和鞭毛中,并在运动调节中发挥作用。因此,在瘦素表达不存在或 mTORC1 缺失的情况下,AMPK 不会受到抑制,从而导致精子活力降低 ( 43 )。

The third signaling pathway that may be activated by leptin is the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway. Insulin receptor substrate (IRS) is phosphorylated and activates PI3K which stimulates the protein kinase (AKT). AKT activates mTORC1 and inhibits FoxO1, which inhibits POMC neurons and activates AGRY neurons (42, 44).

可能被瘦素激活的第三条信号通路是 PI3K/AKT 信号通路。胰岛素受体底物 (IRS) 被磷酸化并激活 PI3K,从而刺激蛋白激酶 (AKT)。AKT 激活 mTORC1 并抑制 FoxO1,后者抑制 POMC 神经元并激活 AGRY 神经元 ( 42 , 44 )。

In a study, it was shown that the proliferation and neuronal differentiation of neural stem cells were supported by the cooperative effect of MAPK/ERK1/2, JAK2/STAT3 and PI3K/AKT signaling pathways induced by leptin (45). In addition, these signaling pathways induced by leptin play an important role in many cyclic activities, such as development, differentiation, renewal and repair. Dysregulation of these leptin-induced signaling pathways leads to pathological processes (46). In one study, dysregulation of leptin signaling in Alzheimer’s disease was reported as evidence of neuronal leptin resistance (47).

在一项研究中,研究表明,瘦素诱导的 MAPK/ERK1/2、JAK2/STAT3 和 PI3K/AKT 信号通路的协同作用支持神经干细胞的增殖和神经元分化 ( 45 )。此外,瘦素诱导的这些信号通路在许多周期性活动中起重要作用,例如发育、分化、更新和修复。这些瘦素诱导的信号通路失调导致病理过程 ( 46 )。在一项研究中,阿尔茨海默病中瘦素信号转导失调被报道为神经元瘦素耐药的证据 ( 47 )。

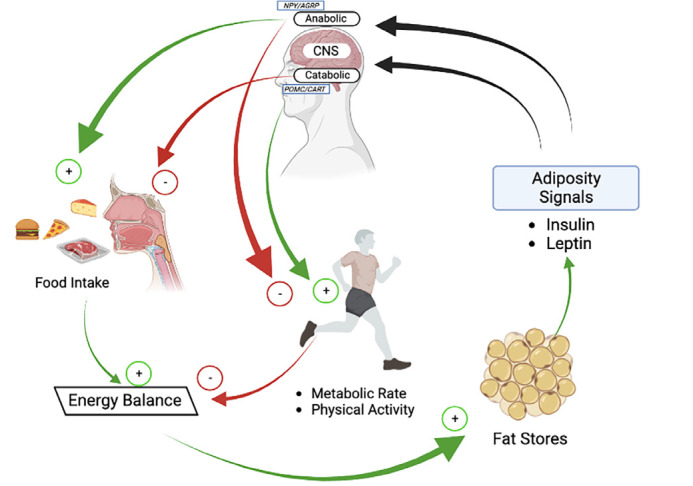

Leptin - hypothalamus - adipocyte axis

When we eat food, the energy obtained may be greater than the energy consumed. To maintain the balance of this energy, fatty acids and glucose in the blood are stored as triglycerides in adipocyte droplets within the white adipose tissue. After about two hours, fat mass increases and leptin is released. Leptin and insulin in the blood both bind to cognate receptors on the hypothalamus, inhibiting anabolic reactions by inhibiting neuropeptides, such as NPY and AGRP and initiating catabolic reactions by stimulating neuropeptides likely POMC and CART. POMC is cleaved by proteolytic enzymes into adrenocorticotropic, β-lipotropic, and α-melanocyte stimulating hormone (α-MSH). These hormones and CART reduce the appetite and increase energy expenditure. After energy consumption and increased lipolysis, fat mass decreases and leptin release stops. In this way, leptin plays a role in maintaining energy balance and regulating body mass (Figure 1) (4, 48, 49). As a result, blood leptin levels are positively correlated with bodily fat mass (2, 6). When a mutation occurs in the Ob gene, the energy balance may be disturbed leading to increased food intake and potentially resulting in severe obesity (Figure 1) (16).

Figure 1.

Leptin plays a role in maintaining energy balance and regulating body mass

AGRP: Agouti-related peptide, NPY: Neuropeptide Y

Leptin resistance

Leptin resistance is a major biological factor in cases of obesity. Leptin resistance, in which the body becomes insensitive to leptin, will prevent the feeling of satiety and lead to increased food intake. SOCS3 and protein tyrosine phosphatase 1B (PTPB1), which are part of the negative feedback mechanism after leptin is expressed, inhibit JAK2 phosphorylation, preventing leptin overactivation. When leptin expression increases significantly in obese men, SOCS3 and PTPB1 concentrations increase significantly, permanently inhibiting leptin expression (50, 51).

All excess fatty acids combine with glycerol and are stored in adipocyte tissue in the form of triglyceride. When some people eat too much, for unknown reasons these fatty acids turn into diacylglycerol, ceramide, or acetyl-CoA and are stored in different locations, such as the liver, kidney, or hypothalamic neurons leading to lipotoxicity. In the hypothalamic neurons, these molecules cause stress of the endoplasmic reticulum. PTPB1, which is located on the surface of the endoplasmic reticulum, and SOCS3 expressions increase, permanently inhibiting leptin expression. Furthermore, endoplasmic reticulum stress in POMC neurons leads to incorrect or absent folding of MSH, so appetite is not reduced and energy is not consumed (52, 53). Moreover, in obese persons, matrix metalloproteinase 2 is activated in the hypothalamus. This enzyme cleaves leptin receptors and leads to inhibition of leptin expression (54).

Another reason for leptin resistance may be the incapacity of leptin to cross the BBB. If leptin cannot pass through the BBB, it will not reach the hypothalamus and exert its effects. A high triglyceride level inhibits this crossing of the BBB (35, 55). Triglycerides may cross the BBB and regulate central leptin receptor resistance (55). The relationship between leptin and triglycerides is not fully known, but in obese rats, fasting reduced triglyceride levels and increased leptin transport across the BBB and satiety increased triglyceride levels and reduced leptin transport across the BBB, so it is thought that the leptin transporter may have a regulative site controlled by the triglyceride (55, 56). A study showed that leptin resistance protected mice from hyperoxia-induced acute lung injury (57). In addition, in the presence of low gene expression or gene mutation in leptin receptors, leptin resistance occurs (9). Blood-testicular barrier (BTB) does not play a role in leptin resistance, indicating that Sertoli, Leydig, and germ cells are exposed to high concentrations of leptin (35).

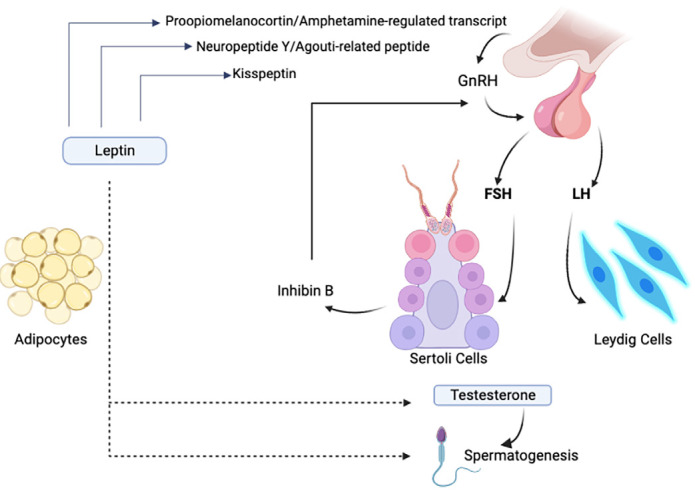

Interaction of leptin and the male HPG axis

Leptin regulates neural pathways that have multidirectional effects, linking energy storage with other physiological activities. It plays a main and important role in regulating reproductive function and securing the vital energy needed for it (3, 36). The leptin released from adipose tissue travels through the blood and reaches the hypothalamus by transport across the BBB. It stimulates POMC, CART, and kisspeptin neurons by binding to the ob-Rb in the hypothalamic paraventricular and arcuate nuclei and inhibits NPY and AGRP, which suppress gonadotropin production. POMC, CART, and kisspeptin stimulate gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) that transfers to the anterior lobe of the pituitary gland and triggers the release of follicle stimulating hormone (FSH) and luteinizing hormone (LH). FSH and LH bind to their receptors in the testis inducing steroidogenesis and spermatogenesis (Figure 2) (12, 58).

Figure 2.

Mechanism of leptin actions on the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis

GnRH: Gonadotropin-releasing hormone, FSH: follicle stimulating hormone, LH: Luteinizing hormone

Leptin affects the testis through the HPG axis and by binding directly to its receptors in the testis and sperm (59). Kisspeptin functions as a stimulator of steroidogenesis. It has been shown that an interaction between leptin and sex hormones can trigger KISS-1/GPR54 signaling to GnRH neurons, suggesting novel mechanisms regulating the onset of puberty (60). Leptin levels peak before puberty, and with the increase in kisspeptin levels, leptin has been reported to be critical for the onset of puberty in males. Studies conclusively showed that kisspeptin neurons are not direct targets of leptin at the onset of puberty. Leptin signaling in kisspeptin neurons occurs only after the completion of sexual maturation and may experience a critical window of sensitivity to the influence of metabolic factors that may alter the onset of fertility (61). Furthermore, altering neonatal leptin fluctuation may alter the timing of pubertal onset and have long-term effects on reproductive and hypothalamic expression of metabolic neuropeptides (62). It also provides the energy and the availability of fats needed for puberty, where some studies have shown that the lack of leptin in boys leads to a delay in puberty (63, 64).

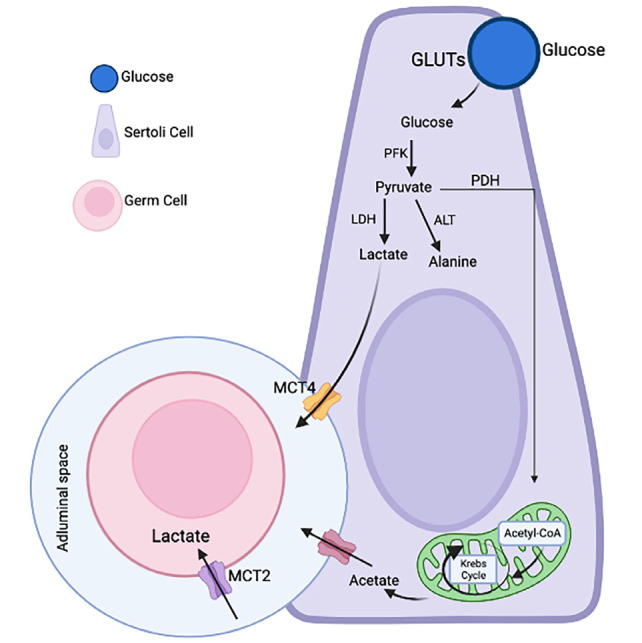

Leptin, sertoli, and germ cells

Sertoli cells are supporting cells found in the epithelium of the seminiferous tubules that have an important role in regulating spermatogenesis. The Sertoli cell contains glucose transporters (GLUTs) and ob-Rb. Glucose enters the Sertoli cell and converts to pyruvate via phosphofructokinase. Pyruvate is converted to alanine through alanine aminotransferase, to lactate through lactate dehydrogenase, and, in mitochondria, to acetyl-CoA via pyruvate dehydrogenase. Through monocarboxylate transporters, lactate passes into the adluminal space and enters the germ cells. Lactate is an important energy source for the germ cell and functions as an anti-apoptotic factor through an unknown mechanism. Acetyl-CoA is then converted into acetate that also enters germ cells, but its role is still unknown (Figure 3). However, acetate is considered the most important carbon source for the synthesis of lipids and cholesterol that are necessary for germ cell division and spermatogenesis. When the leptin level increases in the Sertoli cell, lipolysis increases, and acetate is consumed to synthesize lipids again. It was also observed that when the leptin level increased, lactate was not produced. Therefore, germ cells are damaged and their concentration decreases (65, 66, 67). Thus, leptin triggers the production of factors necessary for spermatogenesis both through the HPG axis and by binding to its receptors in Sertoli cells (68). Moreover, considering the glycolytic flow suitability of Seroli cells, it has been reported that leptin affects mitochondrial physiology in human Sertoli cells and that leptin plays a role in glycolysis (68). Leptin also directly affects germ cells by binding to its receptors in these cells, as it phosphorylates STAT3, which supports stem cell renewal, proliferation, and differentiation (69).

Figure 3.

Metabolic cooperation between Sertoli cells (SCs) and developing germ cells

GLUTs: Glucose transporters, PFK: Phosphofructokinase, PDH: Pyruvate dehydrogenase, LDH: Lactate dehydrogenase, ALT: Alanine aminotransferase, MCT: Monocarboxylate transporters

In a study, Sertoli cells and peritubular myoid cells together form the testis microenvironment (TME). It has been shown that the differentiation of Leydig stem cells is severely impaired as a result of the loss of TME (70). This study was supported by other studies suggesting that cells within the TME are involved in the release of paracrine factors, which are very important for stimulating the differentiation of Leydig cells (71). In a study published in 2022, the important role of leptin, which is secreted by the TME and serves as a paracrine factor, on human Leydig cell differentiation and function was detected (72). In the same study, it was shown that low-level leptin treatment in cells taken from male testis biopsies with azoospermia can also increase testosterone levels and Leydig cell differentiation (72).

Leptin and Leydig cells

Leydig cells are interstitial cells located between the seminiferous tubules in the testes which are responsible for spermatogenesis, the biosynthesis and secretion of androgens, and maintaining secondary sexual characteristics in males. Leydig cells express ob-Rb. Leptin triggers the production of testosterone both through the HPG axis and by binding to its receptors in Leydig cells (25, 73). In a study, leptin was identified as an important paracrine factor released by cells within the TME, modulating Leydig cell differentiation and testosterone release from mature Leydig cells (74). When LH binds to its receptors on the Leydig cell, cAMP levels increase which causes dissociation of the catalytic unit by binding to PKA. This unit enters the nucleus and phosphorylates the GATA4 transcription factor, allowing the expression of the steroidogenic acute regulatory protein (StAR) that transfers cholesterol from the outer membrane of the mitochondria to the inner membrane to produce testosterone (74, 75). Normal levels of leptin are involved in stimulating StAR transcription factors via the PI3K/AKT and ERK1/2 pathways (76).

In order not to produce excessive amounts of steroids, cAMP is converted into AMP by phosphodiesterase. AMP activates AMPK that stops steroidogenesis by inhibiting transcription factors stimulating steroidogenesis and activating transcription factors inhibiting steroidogenesis (77). Since leptin inhibits AMPK when leptin expression is absent, AMPK is not inhibited, and sustained AMPK activity inhibits StAR expression, leading to a decrease in testosterone production (3, 42, 48, 76). A study showed that high leptin levels lead to decreased expression of cAMP-dependent steroidogenic genes (STAR and CYP11a1) in MA-10 Leydig cells (78). Furthermore, another study showed that leptin inhibits the division of prepubertal Leydig cells through a cyclin D-independent mechanism and that cyclin D1 may play a role in leptin-induced differentiation of Leydig cells (79).

The role of leptin on male reproductive function

Since leptin hormone acts by crossing the BTB, it is present in the testicular fluid and seminal plasma and has receptors in spermatozoa, sperm, germ cell, somatic cell, epididymis, Leydig cell, Sertoli cell and epithelial cells of seminal vesicles and prostate (11, 25, 80, 81). Leptin induces FSH and LH release via the HPG axis. Therefore, leptin plays a role in the production of testosterone in Leydig cells and androgen binding protein, testicular fluid, inhibin, activin, and factors necessary for spermatogenesis in Sertoli cells (Figure 2) (12, 82). In an in vitro study, it was shown that leptin application reduced oxidative stress and apoptosis of sperm and positively affected mitochondrial function and energy source (83). Therefore, when leptin is absent or present at very low concentration due to being underweight, the level of steroid hormones decreases, germ cell apoptosis and the expression of pro-apoptotic genes in the testes increase (84) and vacuolization occurs in Sertoli cells (8, 85, 86). In the absence of leptin in ob/ob mice, fertility was restored with leptin therapy (87). Furthermore, when leptin concentration is elevated, the rate of apoptosis of all testis cells and the number of abnormal spermatazoa increases, sperm motility, concentration, and progressive motility decrease, and the BTB is disrupted, especially in the VIII of seminiferous epithelium stages, which is restructured for the pre-leptotene spermatocytes to pass through to enter the stage of meiosis (84, 87, 88). Another study indicates significant morphological, hormonal and enzymatic changes in leptin-deficient mouse testes. Alterations in the enzymatic steroidogenic pathway and enzymes involved in spermatic activity support insights into the fertility failures of these animals (85). In addition, a study has shown that leptin deficiency in mice was associated with impaired spermatogenesis, increased germ cell apoptosis, and upregulated expression of pro-apoptotic genes within the testes (86). It has been reported that dysfunction of spermatogenesis in infertile men associated with varicocele was associated with an increase in leptin concentration and leptin receptor expression, and leptin had local effects on the function of testicles and spermatogenesis (89). Furthermore, a study reported that leptin and leptin receptor expression in the testicles of fertile and infertile patients is due to a systemic effect related to the central neuroendocrine system, androgen levels, or spermatogenic presence, rather than a direct effect on testicular tissue (16).

The interaction of leptin and obesity on the male reproductive system

Leptin has many effects on the reproductive system, and studies have shown that it provides a link between infertility and obesity. The obese male body is resistant to leptin. When leptin is not expressed, AMPK increases, leading to StAR production decreases, and thereby testosterone production decreases. Obesity also reduces the expression of steroidogenic factor-1 which is necessary to produce StAR and P450 side-chain cleavage enzyme which is involved in the synthesis of testosterone (3, 76, 90, 91).

When leptin concentration increases, it decreases the activities of antioxidant enzymes in the cytosol and mitochondria via the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway and increases respiratory chain enzymes in the mitochondria. When the level of antioxidant is decreased in the cytosol, oxidative stress occurs and activates the pro-apoptotic molecules BAX and BAK that enter the mitochondria by changing the permeability of the outer mitochondrial membrane. The increased ROS in the mitochondria crosses into the cytosol and damages DNA. In addition, apoptosis-inducing factor and serine protease high-temperature requirement A2 (HtrA2) from mitochondria pass to the cytosol and cause cell apoptosis by breaking DNA. HtrA2 also separates the cytoskeleton and other cell substrates (Figure 4) (2). Protamine replaces histone during spermiogenesis. This is an important process for protecting the DNA because protamine is capable of packing longer sections of DNA than histone. In an unknown way high leptin levels in sperm reduces the replacement of histone by protamine, so that a smaller number of unpackaged DNA fragments are packaged. Consequently DNA is easily vulnerable to ROS damage (Figure 4) (2, 59, 92). Thus, ROS decreases the concentration of sperm and increases the percentage of abnormal sperm (25, 93). In addition, ROS causes apoptosis of Leydig cells, Sertoli cells, and especially germ cells by damaging DNA, and in so doing also reduces sperm concentration and increases the percentage of abnormal sperm. Moreover, ROS disrupts the tight junction-related proteins (occludin, claudins, and ZO-1), disrupting the BTB. This also causes germ cell damage and negative changes in sperm parameters (88, 94).

Figure 4.

Excess leptin leads to increased ROS via the PI3K\AKT signaling pathway

ROS: Reactive oxygen species, PI3K: Phosphoinositide 3-kinases, HTRA2: High-temperature requirement-A2, AIF: Apoptosis-inducing factor

Since too much fat accumulates around the testis, the scrotal temperature (hyperthermia) increases, causing ROS to increase (95). In obesity, when adipocytes enlarge, the blood supply to them decreases, causing hypoxia and an increase in the accumulation of macrophages in the adipose tissue, which leads to adipocyte inflammation. Under normal conditions, a small amount of interleukin-1 (IL-1) and tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) is produced from adipose tissue, and during inflammation the levels of these proteins increase significantly, also causing ROS (96, 97, 98). The increased ROS oxidizes unsaturated fatty acids in the plasma membrane of the sperm, which leads to formation of malondialdehyde that causes DNA fragmentation and so the concentration of healthy sperm in obese men decreases. Moreover, ROS changes the phospholipid membrane of mitochondria and inhibits oxidative phosphorylation. Hence ATP and then the activity of mitochondria decreases, resulting in decreased sperm motility and progressive motility (99, 100, 101). ROS has been shown in a number of studies to disrupt the tight junction-related proteins of the BTB causing damage to germ cells and increasing the rate of apoptosis in Sertoli and Leydig cells (102, 103, 104).

In the adipocyte cell, testosterone is produced and converted to estradiol by an aromatase. Estradiol inhibits the HPG axis through a negative feedback mechanism and stimulates the proliferation of adipocyte cells. In obese men, increased adipose tissue produces high levels of estradiol which in turn inhibits the HPG axis completely. Therefore testosterone production in the testicle is greatly reduced. Moreover, because testosterone reduces triglyceride accumulation and increases lipolysis in visceral adipose tissue by inhibiting lipoprotein lipase activity, a lack of testosterone leads to increased accumulation of these tissues which causes more estradiol production (105, 106, 107). Furthermore, obese men have low levels of inhibin B, sex hormone-binding globulin, FSH, LH, and androgen receptors (59, 91, 104, 108).

There is a positive correlation between leptin and adipose tissue mass in normal men. In a state of positive energy balance, the body increases the size and number of adipocytes to store excess energy. Thus, the more adipose tissue in the body, the more leptin is released, and the man has no impaired reproductive function associated with leptin (6, 109). In individuals with homozygous Ob gene mutation (Ob/Ob), no leptin is produced. Therefore, the satiety signal does not interact with the hypothalamus and so the person continues to eat food and gains weight, and this person has reproductive failure associated with leptin deficiency (110). When the person continues to eat constantly, too much fat is stored, hence leptin is released at a high level. In this case, the body becomes unresponsive to leptin to protect itself from high leptin concentration, so the satiety signal is again not detected and the person continues to eat and gain excess weight, and this person has impaired reproductive function associated with leptin deficiency (7, 87, 111).

Clinical and experimental studies

Studies demonstrated that seminal plasma leptin and its receptors in the testis were elevated in a varicocele patient and this elevation was inversely correlated with sperm density, sperm motility, the weight of testis, the diameter of seminiferous tubules and the thickness of the seminiferous epithelium, and positively correlated with ROS levels and the rate of sperm apoptosis, and it was concluded that leptin was the cause of sperm apoptosis by raising ROS levels (13, 24, 89).

In patients with leukocytospermia, studies have shown that seminal plasma leptin was elevated and that this elevation was inversely associated with sperm motility, and positively associated with ROS levels, TNF-α levels, and rate of sperm apoptosis. Thus, leptin was the cause of sperm apoptosis by raising ROS and TNF-α levels. Leukocytes migrate to the inflammation area in the genital system in leukocytospermia and phagocytose the damaged cells. Leptin receptors are found in macrophages and monocytes. When inflammation occurs, leptin binds to these receptors, causing macrophages and monocytes to proliferate, produce and release IL-1 and TNF-α and initiate apoptosis. TNF-α activates the caspase system by binding to its receptors in damaged cells. When the macrophage phagocytoses apoptotic bodies, which formed as a result of apoptosis, ROS is released. ROS causes apoptosis of sperm. In this way, leptin increases the release of TNF-α and IL-1. These also increase leptin mRNA expression in adipose tissue for an unknown reason, which means that there is a positive relationship between them. Also, leptin receptors are found in neutrophils and when leptin binds to them, it causes ROS production. As a result, leptin contributes to immune responses affecting fertility (13, 112, 113, 114).

The leptin level was low in male Akita type 1 diabetic mice and leptin monotherapy was proven to rescue spermatogenesis in these mice. Akita mice have a mutation in the insulin 2 gene that results in hyperglycemia and eventually type 1 diabetes. In Akita homozygous mice, body mass index, testicular and seminal vesicle weights, LH, testosterone, leptin, and insulin levels are low and spermatogenesis is absent (14, 115). There is a relationship between insulin and leptin, as they converge at the PI3K signaling pathway in hypothalamic neurons. When they bind to their receptors, they initiate this signal and activate AKT, which stimulates mTORC1, which contributes to leptin secretion and inhibits FoxO1, which works against STAT3. In this way, insulin increases leptin secretion and expression (14, 29, 116). In adipocyte cells, insulin activates the vesicle containing GLUT4 through the same signaling pathway, causing GLUT4 to open and glucose to enter the cell. Moreover, insulin stimulates the formation of fatty acids by increasing the activity of fatty acid synthase and acetyl-CoA carboxylase through the same signaling pathway (117, 118). Every three fatty acid molecules combine with glycerol, which is synthesized from glucose, to form triglycerides, which are stored in lipid droplets. Thus, insulin stimulates leptin release by increasing lipid synthesis (119). In type 1 diabetes, the decrease in insulin causes the fatty acid storage to decrease, so less leptin is released from the adipose tissue and infertility occurs (120, 121). Low insulin causes infertility through both leptin deficiency and hyperglycemia, as hyperglycemia causes excess ROS production by various mechanisms (122, 123). Leptin monotherapy, in the absence of exogenous insulin, in homozygous Akita mice significantly improved reproductive system functions and rescued Spermatogenesis. Consequently, infertility in patients with type 1 diabetes is not due to insulin deficiency but to leptin deficiency (14). In summary, studies on leptin metabolism and molecular signaling mechanism are shown in Table 1.

Table 1. The effects of leptin on male reproductive system. Studies in which the intracellular, intercellular, metabolic, and systemic effects of leptin are summarized.

|

Effects of leptin and molecular mechanism | |

|

The leptin hormone produced from adipose tissue binds to ob-Rb and causes JAK/STAT3 signal activation. This signal activates POMC and CART neurons in the hypothalamus and inhibits AGRP and NPY neurons. |

- Landry et al. (35) - Francisco et al. (40) |

|

Leptin binds to the receptor, ERK1/2-mediated mTORC1 is activated, while AMPK, which functions as an energy sensor, is inhibited. Thus, leptin ensures energy consumption. |

- Kwon et al. (41) - Wauman et al. (42) |

|

In the absence of leptin expression or when mTORC1 is deleted, AMPK located in the permine midpiece and flagellum is not inhibited, resulting in decreased sperm motility. |

- Martin-Hidalgo et al. (43) |

|

Leptin-mediated IRS is phosphorylated and PI3K is activated. AKT activates mTORC1 and inhibits FoxO1 (FoxO1 inhibits POMC neurons and activates AGRY neurons). |

- Wauman et al. (42) - Zhou and Rui (44) |

|

Kisspeptin acts as a stimulator of steroidogenesis. The prepubertal level of leptin reaches its peak and leads to a significant increase in the secretion of Kisspeptin, a stimulator of steroidogenesis. Leptin plays an important role in the onset of puberty in male. |

- Elias (64) - Zhang and Gong (63) |

|

Leptin induces the release of FSH and LH through the HPG axis. It plays a role in the production of testosterone in Leydig cells and androgen-binding protein in Sertoli cells, testicular fluid, inhibin, activin and factors necessary for spermatogenesis. |

- Ramos and Zamoner (12) - Cheng and Mruk (80) - Zhang and Gong (63) |

|

LH hormone raises cAMP levels in Leydig cell, which in turn binds to PKA. It phosphorylates the transcription factor GATA4, enabling the expression of StAR and producing testosterone. |

- Abdou et al. (74) - Martin and Touaibia (75) |

|

Normal leptin levels are involved in the induction of StAR transcription factors via the PI3K/AKT and ERK1/2 pathways. |

- Roumaud and Martin (76) |

|

Leptin triggers the production of factors necessary for spermatogenesis by binding to its receptors in Sertoli cells. Since it phosphorylates STAT3, which supports stem cell renewal, proliferation and differentiation, it directly affects germ cells by binding to its receptors in these cells. |

- El-Hefnawy et al. (69) |

|

Leptin is secreted by the TMJ and acts as a paracrine factor. It is involved in human LSC function and differentiation. |

- Arora et al. (72) |

|

ROS disrupts the tight junction related proteins of the BTB causing damage to germ cells and increases the rate of apoptosis in Sertoli and Leydig cells. |

- Zhao et al. (103) - Fan et al. (104) |

Conclusion

Leptin plays a unique and critical role in regulating energy expenditure, adipose tissue mass, and reproductive functions in males. It stimulates the hypothalamus to activate neural pathways that reduce appetite and increase energy consumption and stimulates the secretion of gonadotropins that affect the Leydig and Sertoli cells, leading to steroidogenesis and supporting spermatogenesis. Therefore, leptin links body weight and fertility. Although leptin levels increase in weight gain, body weight loss is greatly reduced. Leptin receptors are found in all testicular cells and sperm, as leptin regulates reproductive functions independently of the hypothalamus through direct binding to its receptors. It supports testosterone production in Leydig cells and sperm motility by regulating AMPK levels and also supports germ cell regeneration, proliferation, and differentiation.

The role of leptin remains unclear in germ, sperm and Sertoli cells. In obese men, an increase in fat tissue acts to increase the level of leptin, followed by the occurrence of leptin resistance. When leptin expression decreases, it does not support the HPG axis and thus disrupts reproductive functions. Moreover, a high concentration of leptin leads to a decrease in testosterone secretion in Leydig cells, damage to germ cells, and increased levels of ROS that reduce the concentration, motility, and progressive motility of sperm and increase the percentage of abnormal sperm and apoptosis of Leydig, Sertoli, and germ cells by damaging DNA. High leptin concentration also disrupts the BTB. Given that the BTB does not play a role in leptin resistance, it is usual for testes and sperm cells to be exposed to high leptin levels. Leptin insufficiency due to being underweight or a mutation in the Ob gene also leads to a significant reduction in steroidogenesis and infertility.

In general, low leptin impairs reproductive functions by not supporting the HPG axis to secrete gonadotropins, and high leptin impairs reproductive functions by directly affecting the functions of testicular and sperm cells. More studies are still needed to clarify how leptin works and how its levels affect the male reproductive system, as the results of these studies may have a significant impact on treating impaired fertility.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: No conflict of interest is declared by the authors.

Financial Disclosure: The authors declared that this study received no financial support.

References

- 1.Robaczyk M, Smiarowska M, Krzyzanowska-Swiniarska B. The ob gene product (leptin)--a new hormone of adipose tissue. Przegl Lek. 1997;54(5):348–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Almabhouh FA, Md Mokhtar AH, Malik IA, Aziz NAAA, Durairajanayagam D, Singh HJ. Leptin and reproductive dysfunction in obese me. Andrologia. 2020;52(1):e13433. doi: 10.1111/and.13433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moreira BP, Monteiro MP, Sousa M, Oliveira PF, Alves MG. Insights into leptin signaling and male reproductive health: the missing link between overweight and subfertility? Biochem J. 2018;475:3535–60. doi: 10.1042/BCJ20180631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schwartz MW, Woods SC, Seeley RJ, Barsh GS, Baskin DG, Leibel RL. Is the energy homeostasis system inherently biased toward weight gain? Diabetes. 2003;52(2):232–8. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.52.2.232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barabás K, Szabó-Meleg E, Ábrahám IM. Effect of inflammation on female gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) neurons: mechanisms and consequences. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21:529. doi: 10.3390/ijms21020529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Al Maskari MY, Alnaqdy AA. Correlation between serum leptin levels, body mass ındex and obesity in omanis. Sultan Qaboos Univ Med J. 2006;6:27–31. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Enriori PJ, Evans AE, Sinnayah P, Cowley MA. Leptin resistance and obesity. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2006;14(Suppl 5):254S–8. doi: 10.1038/oby.2006.319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boutari C, Pappas PD, Mintziori G, Nigdelis MP, Athanasiadis L, Goulis DG. The effect of underweight on female and male reproduction. Metabolism. 2020;107:154229. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2020.154229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sáinz N, González-Navarro CJ, Martínez JA, Moreno-Aliaga MJ. Leptin signaling as a therapeutic target of obesity. Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2015;19(7):893–909. doi: 10.1517/14728222.2015.1018824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gruzdeva O, Borodkina D, Uchasova E, Dyleva Y, Barbarash O. Leptin resistance: underlying mechanisms and diagnosis. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes. 2019;12:191–8. doi: 10.2147/DMSO.S182406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jope T, Lammert A, Kratzsch J, Paasch U, Glander HJ. Leptin and leptin receptor in human seminal plasma and in human spermatozoa. Int J Androl. 2003;26:335–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2605.2003.00434.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ramos CF, Zamoner A. Thyroid hormone and leptin in the testis. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2014;5:198. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2014.00198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang H, Lv Y, Hu K, Feng T, Jin Y, Wang Y. Seminal plasma leptin and spermatozoon apoptosis in patients with varicocele and leucocytospermia. Andrologia. 2015;47(6):655–61. doi: 10.1111/and.12313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schoeller EL, Chi M, Drury A, Bertschinger A, Esakky P, Moley KH. Leptin monotherapy rescues spermatogenesis in male Akita type 1 diabetic mice. Endocrinology. 2014;155(8):2781–6. doi: 10.1210/en.2014-1119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Licinio J, Mantzoros C, Negrão AB, Cizza G, Wong ML, Bongiorno PB. Human leptin levels are pulsatile and inversely related to pituitary-adrenal function. Nat Med. 1997;3:575–9. doi: 10.1038/nm0597-575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ishikawa T, Fujioka H, Ishimura T, Takenaka A, Fujisawa M. Expression of leptin and leptin receptor in the testis of fertile and infertile patients. Andrologia. 2007;39(1):22–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0272.2006.00754.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Niederberger C. Re: Sperm motility inversely correlates with seminal leptin levels in idiopathic asthenozoospermia. J Urol. 2015;194(1):169–71. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2015.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bjørbaek C, Elmquist JK, Michl P, Ahima RS, van Bueren A, McCall AL. Expression of leptin receptor isoforms in rat brain microvessels. Endocrinology. 1998;139(8):3485–91. doi: 10.1210/endo.139.8.6154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Elmquist JK, Bjørbaek C, Ahima RS, Flier JS, Saper CB. Distributions of leptin receptor mRNA isoforms in the rat brain. J Comp Neurol. 1998;395:535–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee GH, Proenca R, Montez JM, Carroll KM, Darvishzadeh JG, Lee JI. Abnormal splicing of the leptin receptor in diabetic mice. Nature. 1996;379(6566):632–5. doi: 10.1038/379632a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Martínez-Sánchez N. There and back again: leptin actions in white adipose tissue. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21:6039. doi: 10.3390/ijms21176039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mantzoros CS, Magkos F, Brinkoetter M, Sienkiewicz E, Dardeno TA, Kim SY. Leptin in human physiology and pathophysiology. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2011;301:E567–84. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00315.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Aquila S, Gentile M, Middea E, Catalano S, Morelli C, Pezzi V. Leptin secretion by human ejaculated spermatozoa. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90:4753–61. doi: 10.1210/jc.2004-2233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang J, Jin PP, Gong M, Yi QT, Zhu RJ. Role of leptin and the leptin receptor in the pathogenesis of varicocele-induced testicular dysfunction. Mol Med Rep. 2018;17:7065–72. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2018.8753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Almabhouh FA, Osman K, Siti Fatimah I, Sergey G, Gnanou J, Singh HJ. Effects of leptin on sperm count and morphology in Sprague-Dawley rats and their reversibility following a 6-week recovery period. Andrologia. 2015;47(7):751–8. doi: 10.1111/and.12325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Soyupek S, Armağan A, Serel TA, Hoşcan MB, Perk H, Karaöz E. Leptin expression in the testicular tissue of fertile and infertile men. Arch Androl. 2005;51:239–46. doi: 10.1080/01485010590919666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Adya R, Tan BK, Randeva HS. Differential effects of leptin and adiponectin in endothelial angiogenesis. J Diabetes Res. 2015;2015:648239. doi: 10.1155/2015/648239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vargas VE, Landeros RV, Lopez GE, Zheng J, Magness RR. Uterine artery leptin receptors during the ovarian cycle and pregnancy regulate angiogenesis in ovine uterine artery endothelial cells†. Biol Reprod. 2017;96(4):866–76. doi: 10.1093/biolre/iox008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Park HK, Ahima RS. Leptin signaling. F1000prime Rep. 2014;6:73. doi: 10.12703/P6-73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bjørbaek C, Uotani S, da Silva B, Flier JS. Divergent signaling capacities of the long and short isoforms of the leptin receptor. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:32686–95. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.51.32686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Barr VA, Lane K, Taylor SI. Subcellular localization and internalization of the four human leptin receptor isoforms. J Biol Chem. 1999;274(30):21416–24. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.30.21416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang Y, Wan R, Hu C. Leptin/obR signaling exacerbates obesity-related neutrophilic airway inflammation through inflammatory M1 macrophages. Mol Med. 2023;29(1):100. doi: 10.1186/s10020-023-00702-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tartaglia LA. The leptin receptor. J Biol Chem. 1997;272(10):6093–6. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.10.6093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Smith GD, Jackson LM, Foster DL. Leptin regulation of reproductive function and fertility. Theriogenology. 2002;57(1):73–86. doi: 10.1016/s0093-691x(01)00658-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Landry D, Cloutier F, Martin LJ. Implications of leptin in neuroendocrine regulation of male reproduction. Reprod Biol. 2013;13(1):1–14. doi: 10.1016/j.repbio.2012.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hofny ER, Ali ME, Abdel-Hafez HZ, Kamal Eel-D, Mohamed EE, Abd El-Azeem HG. Semen parameters and hormonal profile in obese fertile and infertile males. Fertil Steril. 2010;94:581–4. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2009.03.085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ahima RS, Osei SY. Leptin signaling. Physiol Behav. 2004;81(2):223–41. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2004.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Münzberg H, Björnholm M, Bates SH, Myers MG Jr. Leptin receptor action and mechanisms of leptin resistance. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2005;62(6):642–52. doi: 10.1007/s00018-004-4432-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Münzberg H, Myers MG Jr. Molecular and anatomical determinants of central leptin resistance. Nat Neurosci. 2005;8(5):566–70. doi: 10.1038/nn1454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Francisco V, Pino J, Campos-Cabaleiro V, Ruiz-Fernández C, Mera A, Gonzalez-Gay MA. Obesity, fat mass and immune system: role for leptin. Front Physiol. 2018;9:640. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2018.00640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kwon O, Kim KW, Kim MS. Leptin signalling pathways in hypothalamic neurons. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2016;73(7):1457–77. doi: 10.1007/s00018-016-2133-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wauman J, Zabeau L, Tavernier J. The leptin receptor complex: heavier than expected?. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2017;8:30. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2017.00030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Martin-Hidalgo D, Hurtado de Llera A, Calle-Guisado V, Gonzalez-Fernandez L, Garcia-Marin L, Bragado MJ. AMPK function in mammalian spermatozoa. Int J Mol Sci. 2018;19(11):3293. doi: 10.3390/ijms19113293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhou Y, Rui L. Leptin signaling and leptin resistance. Front Med. 2013;7(2):207–22. doi: 10.1007/s11684-013-0263-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tan R, Hu X, Wang X, Sun M, Cai Z, Zhang Z. Leptin promotes the proliferation and neuronal differentiation of neural stem cells through the cooperative action of MAPK/ERK1/2, JAK2/STAT3 and PI3K/AKT signaling pathways. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24:15151. doi: 10.3390/ijms242015151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Evans MC, Lord RA, Anderson GM. Multiple leptin signalling pathways in the control of metabolism and fertility: a means to different ends? Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(17):9210. doi: 10.3390/ijms22179210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bonda DJ, Stone JG, Torres SL, Siedlak SL, Perry G, Kryscio R. Dysregulation of leptin signaling in Alzheimer disease: evidence for neuronal leptin resistance. J Neurochem. 2014;128:162–72. doi: 10.1111/jnc.12380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kelesidis T, Kelesidis I, Chou S, Mantzoros CS. Narrative review: the role of leptin in human physiology: emerging clinical applications. Ann Intern Med. 2010;152:93–100. doi: 10.1059/0003-4819-152-2-201001190-00008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Anton SD, Moehl K, Donahoo WT, Marosi K, Lee SA, Mainous AG 3rd. Flipping the metabolic switch: understanding and applying the health benefits of fasting. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2018;26(2):254–68. doi: 10.1002/oby.22065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yang R, Barouch LA. Leptin signaling and obesity: cardiovascular consequences. Circ Res. 2007;101(6):545–59. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.156596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cho H. Protein tyrosine phosphatase 1B (PTP1B) and obesity. Vitam Horm. 2013;91:405–24. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-407766-9.00017-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Li LO, Klett EL, Coleman RA. Acyl-CoA synthesis, lipid metabolism and lipotoxicity. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010;1801(3):246–51. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2009.09.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ramírez S, Claret M. Hypothalamic ER stress: a bridge between leptin resistance and obesity. FEBS Lett. 2015;589(14):1678–87. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2015.04.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mazor R, Friedmann-Morvinski D, Alsaigh T, Kleifeld O, Kistler EB, Rousso-Noori L. Cleavage of the leptin receptor by matrix metalloproteinase-2 promotes leptin resistance and obesity in mice. Sci Transl Med. 2018;10:eaah6324. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aah6324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Banks WA, Farr SA, Salameh TS, Niehoff ML, Rhea EM, Morley JE. Triglycerides cross the blood-brain barrier and induce central leptin and insulin receptor resistance. Int J Obes (Lond) 2018;42:391–7. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2017.231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Banks WA, Coon AB, Robinson SM, Moinuddin A, Shultz JM, Nakaoke R. Triglycerides induce leptin resistance at the blood-brain barrier. Diabetes. 2004;53(5):1253–60. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.53.5.1253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bellmeyer A, Martino JM, Chandel NS, Scott Budinger GR, Dean DA, Mutlu GM. Leptin resistance protects mice from hyperoxia-induced acute lung injury. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;175(6):587–94. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200603-312OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wiesner G, Vaz M, Collier G, Seals D, Kaye D, Jennings G. Leptin is released from the human brain: influence of adiposity and gender. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1999;84:2270–4. doi: 10.1210/jcem.84.7.5854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Amjad S, Baig M, Zahid N, Tariq S, Rehman R. Association between leptin, obesity, hormonal interplay and male infertility. Andrologia. 2019;51(1):e13147. doi: 10.1111/and.13147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Morelli A, Marini M, Mancina R, Luconi M, Vignozzi L, Fibbi B. Sex steroids and leptin regulate the "first Kiss" (KiSS 1/G-protein-coupled receptor 54 system) in human gonadotropin-releasing-hormone-secreting neuroblasts. J Sex Med. 2008;5:1097–113. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2008.00782.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Cravo RM, Frazao R, Perello M, Osborne-Lawrence S, Williams KW, Zigman JM. Leptin signaling in kiss1 neurons arises after pubertal development. PLoS One. 2013;8(3):e58698. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0058698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Mela V, Jimenez S, Freire-Regatillo A, Barrios V, Marco EM, Lopez-Rodriguez AB. Blockage of neonatal leptin signaling induces changes in the hypothalamus associated with delayed pubertal onset and modifications in neuropeptide expression during adulthood in male rats. Peptides. 2016;86:63–71. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2016.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zhang J, Gong M. Review of the role of leptin in the regulation of male reproductive function. Andrologia. 2018 Feb 20. doi: 10.1111/and.12965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Elias CF. Leptin action in pubertal development: recent advances and unanswered questions. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2012;23(1):9–15. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2011.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Bernardino RL, Marinelli RA, Maggio A, Gena P, Cataldo I, Alves MG. Hepatocyte and sertoli cell aquaporins, recent advances and research trends. Int J Mol Sci. 2016;17:1096. doi: 10.3390/ijms17071096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Martins AD, Moreira AC, Sá R, Monteiro MP, Sousa M, Carvalho RA. Leptin modulates human Sertoli cells acetate production and glycolytic profile: a novel mechanism of obesity-induced male infertility? Biochim Biophys Acta. 2015;1852(9):1824–32. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2015.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Moreira BP, Silva AM, Martins AD, Monteiro MP, Sousa M, Oliveira PF. Effect of leptin in human sertoli cells mitochondrial physiology. Reprod Sci. 2021;28:920–31. doi: 10.1007/s43032-020-00328-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Nargund VH. Effects of psychological stress on male fertility. Nat Rev Urol. 2015;12(7):373–82. doi: 10.1038/nrurol.2015.112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.El-Hefnawy T, Ioffe S, Dym M. Expression of the leptin receptor during germ cell development in the mouse testis. Endocrinology. 2000;141(7):2624–30. doi: 10.1210/endo.141.7.7542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Arora H, Zuttion MSSR, Nahar B, Lamb D, Hare JM, Ramasamy R. Subcutaneous leydig stem cell autograft: a promising strategy to increase serum testosterone. Stem Cells Transl Med. 2019;8(1):58–65. doi: 10.1002/sctm.18-0069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Li X, Wang Z, Jiang Z, Guo J, Zhang Y, Li C. Regulation of seminiferous tubule-associated stem Leydig cells in adult rat testes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016;113:2666–71. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1519395113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Arora H, Qureshi R, Khodamoradi K, Seetharam D, Parmar M, Van Booven DJ. Leptin secreted from testicular microenvironment modulates hedgehog signaling to augment the endogenous function of Leydig cells. Cell Death Dis. 2022;13(3):208. doi: 10.1038/s41419-022-04658-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Giovambattista A, Suescun MO, Nessralla CC, França LR, Spinedi E, Calandra RS. Modulatory effects of leptin on leydig cell function of normal and hyperleptinemic rats. Neuroendocrinology. 2003;78(5):270–9. doi: 10.1159/000074448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Abdou HS, Bergeron F, Tremblay JJ. A cell-autonomous molecular cascade initiated by AMP-activated protein kinase represses steroidogenesis. Mol Cell Biol. 2014;34(23):4257–71. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00734-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Martin LJ, Touaibia M. Improvement of testicular steroidogenesis using flavonoids and isoflavonoids for prevention of late-onset male hypogonadism. Antioxidants (Basel) 2020;9(3):237. doi: 10.3390/antiox9030237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Roumaud P, Martin LJ. Roles of leptin, adiponectin and resistin in the transcriptional regulation of steroidogenic genes contributing to decreased Leydig cells function in obesity. Horm Mol Biol Clin Investig. 2015;24(1):25–45. doi: 10.1515/hmbci-2015-0046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Tremblay JJ. Molecular regulation of steroidogenesis in endocrine Leydig cells. Steroids. 2015;103:3–10. doi: 10.1016/j.steroids.2015.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Landry DA, Sormany F, Haché J, Roumaud P, Martin LJ. Steroidogenic genes expressions are repressed by high levels of leptin and the JAK/STAT signaling pathway in MA-10 Leydig cells. Mol Cell Biochem. 2017;433(1-2):79–95. doi: 10.1007/s11010-017-3017-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Fombonne J, Charrier C, Goddard I, Moyse E, Krantic S. Leptin-mediated decrease of cyclin A2 and increase of cyclin D1 expression: relevance for the control of prepubertal rat Leydig cell division and differentiation. Endocrinology. 2007;148(5):2126–37. doi: 10.1210/en.2006-1218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Cheng CY, Mruk DD. The blood-testis barrier and its implications for male contraception. Pharmacol Rev. 2012;64(1):16–64. doi: 10.1124/pr.110.002790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Yaba A, Bozkurt ER, Demir N. mTOR expression in human testicular seminoma. Andrologia. 2016;48(6):702–7. doi: 10.1111/and.12504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Smith LB, Walker WH. The regulation of spermatogenesis by androgens. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2014;30:2–13. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2014.02.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Gao Y, Zhao G, Song Y, Haire A, Yang A, Zhao X. Presence of leptin and its receptor in the ram reproductive system and in vitro effect of leptin on sperm quality. PeerJ. 2022;10:e13982. doi: 10.7717/peerj.13982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Önel T, Ayla S, Keskin İ, Parlayan C, Yiğitbaşı T, Kolbaşı B. Leptin in sperm analysis can be a new indicator. Acta Histochem. 2019;121(1):43–9. doi: 10.1016/j.acthis.2018.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Martins FF, Aguila MB, Mandarim-de-Lacerda CA. Impaired steroidogenesis in the testis of leptin-deficient mice (ob/ob -/-). Acta Histochem. 2017;119(5):508–15. doi: 10.1016/j.acthis.2017.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Bhat GK, Sea TL, Olatinwo MO, Simorangkir D, Ford GD, Ford BD. Influence of a leptin deficiency on testicular morphology, germ cell apoptosis, and expression levels of apoptosis-related genes in the mouse. J Androl. 2006;27:302–10. doi: 10.2164/jandrol.05133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Malik IA, Durairajanayagam D, Singh HJ. Leptin and its actions on reproduction in males. Asian J Androl. 2019;21(3):296–9. doi: 10.4103/aja.aja_98_18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Wang X, Zhang X, Hu L, Li H. Exogenous leptin affects sperm parameters and impairs blood testis barrier integrity in adult male mice. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2018;16:55. doi: 10.1186/s12958-018-0368-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Chen B, Guo JH, Lu YN, Ying XL, Hu K, Xiang ZQ. Leptin and varicocele-related spermatogenesis dysfunction: animal experiment and clinical study. Int J Androl. 2009;32:532–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2605.2008.00892.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Yi X, Gao H, Chen D, Tang D, Huang W, Li T. Effects of obesity and exercise on testicular leptin signal transduction and testosterone biosynthesis in male mice. Am J Physiol Regul Integt Comp Physiol. 2017;312:R501–10. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00405.2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Chavarro JE, Toth TL, Wright DL, Meeker JD, Hauser R. Body mass index in relation to semen quality, sperm DNA integrity, and serum reproductive hormone levels among men attending an infertility clinic. Fertil Steril. 2010;93(7):2222–31. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2009.01.100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Wang T, Gao H, Li W, Liu C. Essential role of histone replacement and modifications in male fertility. Front Genet. 2019;10:962. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2019.00962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Abbasihormozi S, Shahverdi A, Kouhkan A, Cheraghi J, Akhlaghi AA, Kheimeh A. Relationship of leptin administration with production of reactive oxygen species, sperm DNA fragmentation, sperm parameters and hormone profile in the adult rat. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2013;287(6):1241–9. doi: 10.1007/s00404-012-2675-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Darbandi S, Agarwal A, Sengupta P, Durairajanayagam D, Henkel R. Reactive oxygen species and male reproductive hormones. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2018;16:87. doi: 10.1186/s12958-018-0406-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Fariello RM, Pariz JR, Spaine DM, Cedenho AP, Bertolla RP, Fraietta R. Association between obesity and alteration of sperm DNA integrity and mitochondrial activity. BJU Int. 2012;110(6):863–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2011.10813.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Greenberg AS, Obin MS. Obesity and the role of adipose tissue in inflammation and metabolism. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006;83(2):461S–5S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/83.2.461S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Makki K, Froguel P, Wolowczuk I. Adipose tissue in obesity-related inflammation and insulin resistance: cells, cytokines, and chemokines. ISRN Inflamm. 2013;2013:139239. doi: 10.1155/2013/139239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Ellulu MS, Patimah I, Khaza'ai H, Rahmat A, Abed Y. Obesity and inflammation: the linking mechanism and the complications. Arch Med Sci. 2017;13(4):851–63. doi: 10.5114/aoms.2016.58928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Sanocka D, Kurpisz M. Reactive oxygen species and sperm cells. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2004;2:12. doi: 10.1186/1477-7827-2-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Dutta S, Majzoub A, Agarwal A. Oxidative stress and sperm function: A systematic review on evaluation and management. Arab J Urol. 2019;17(2):87–97. doi: 10.1080/2090598X.2019.1599624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Dupont C, Faure C, Sermondade N, Boubaya M, Eustache F, Clément P. Obesity leads to higher risk of sperm DNA damage in infertile patients. Asian J Androl. 2013;15(5):622–5. doi: 10.1038/aja.2013.65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Park YJ, Pang MG. Mitochondrial functionality in male fertility: from spermatogenesis to fertilization. Antioxidants (Basel) 2021;10(1):98. doi: 10.3390/antiox10010098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Zhao J, Zhai L, Liu Z, Wu S, Xu L. Leptin level and oxidative stress contribute to obesity-induced low testosterone in murine testicular tissue. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2014;2014:190945. doi: 10.1155/2014/190945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Fan Y, Liu Y, Xue K, Gu G, Fan W, Xu Y. Diet-induced obesity in male C57BL/6 mice decreases fertility as a consequence of disrupted blood-testis barrier. PLoS One. 2015;10(4):e0120775. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0120775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Phillips KP, Tanphaichitr N. Mechanisms of obesity-induced male infertility. Expert Rev Endocrinol Metab. 2010;5(2):229–51. doi: 10.1586/eem.09.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Fejes I, Koloszár S, Závaczki Z, Daru J, Szöllösi J, Pál A. Effect of body weight on testosterone/estradiol ratio in oligozoospermic patients. Arch Androl. 2006;52(2):97–102. doi: 10.1080/01485010500315479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Mårin P, Arver S. Androgens and abdominal obesity. Baillieres Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1998;12(3):441–51. doi: 10.1016/s0950-351x(98)80191-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Alves MG, Jesus TT, Sousa M, Goldberg E, Silva BM, Oliveira PF. Male fertility and obesity: are ghrelin, leptin and glucagon-like peptide-1 pharmacologically relevant? Curr Pharm Des. 2016;22(7):783–91. doi: 10.2174/1381612822666151209151550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Paul RF, Hassan M, Nazar HS, Gillani S, Afzal N, Qayyum I. Effect of body mass index on serum leptin levels. J Ayub Medl Coll Abbottabad. 2011;23:40–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Montague CT, Farooqi IS, Whitehead JP, Soos MA, Rau H, Wareham NJ. Congenital leptin deficiency is associated with severe early-onset obesity in humans. Nature. 1997;387(6636):903–8. doi: 10.1038/43185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Martins Mdo C, Lima Faleiro L, Fonseca A. Relationship between leptin and body mass and metabolic syndrome in an adult population. Rev Port Cardiol. 2012;31:711–9. doi: 10.1016/j.repc.2012.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Fernández-Riejos P, Najib S, Santos-Alvarez J, Martín-Romero C, Pérez-Pérez A, González-Yanes C. Role of leptin in the activation of immune cells. Mediators Inflamm. 2010;2010:568343. doi: 10.1155/2010/568343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.La Cava A. Leptin in inflammation and autoimmunity. Cytokine. 2017;98:51–8. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2016.10.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Xin S, Hao Y, Zhi-Peng M, Nanhe L, Bin C. Chronic epididymitis and leptin and their associations with semen characteristics in men with infertility. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2019;82(1):e13126. doi: 10.1111/aji.13126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Schoeller EL, Chi M, Drury A, Bertschinger A, Esakky P, Moley KH. Leptin monotherapy rescues spermatogenesis in male Akita type 1 diabetic mice. Endocrinology. 2014;155(8):2781–6. doi: 10.1210/en.2014-1119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Tsubai T, Noda Y, Ito K, Nakao M, Seino Y, Oiso Y. Insulin elevates leptin secretion and mRNA levels via cyclic AMP in 3T3-L1 adipocytes deprived of glucose. Heliyon. 2016;2(11):e00194. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2016.e00194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Chadt A, Al-Hasani H. Glucose transporters in adipose tissue, liver, and skeletal muscle in metabolic health and disease. Pflugers Arch. 2020;472(9):1273–98. doi: 10.1007/s00424-020-02417-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Montessuit C, Lerch R. Regulation and dysregulation of glucose transport in cardiomyocytes. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2013;1833(4):848–56. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2012.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Rui L. Energy metabolism in the liver. Compr Physiol. 2014;4(1):177–97. doi: 10.1002/cphy.c130024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Condorelli RA, La Vignera S, Mongioì LM, Alamo A, Calogero AE. Diabetes mellitus and ınfertility: different pathophysiological effects in type 1 and type 2 on sperm function. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2018;9:268. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2018.00268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.La Vignera S, Condorelli RA, Di Mauro M, Lo Presti D, Mongioì LM, Russo G. Reproductive function in male patients with type 1 diabetes mellitus. Andrology. 2015;3(6):1082–7. doi: 10.1111/andr.12097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Maresch CC, Stute DC, Alves MG, Oliveira PF, de Kretser DM, Linn T. Diabetes-induced hyperglycemia impairs male reproductive function: a systematic review. Hum Reprod Update. 2018;24(1):86–105. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmx033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Amaral S, Oliveira PJ, Ramalho-Santos J. Diabetes and the impairment of reproductive function: possible role of mitochondria and reactive oxygen species. Curr Diabetes Rev. 2008;4(1):46–54. doi: 10.2174/157339908783502398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]