Humans 101 人类 101

Laziness Does Not Exist 懒惰不存在

But unseen barriers do 但看不见的障碍确实如此

插图:Ashley Becerra

![]() I’ve been a psychology professor since 2012. In the past six years, I’ve witnessed students of all ages procrastinate on papers, skip presentation days, miss assignments, and let due dates fly by. I’ve seen promising prospective grad students fail to get applications in on time; I’ve watched PhD candidates take months or years revising a single dissertation draft; I once had a student who enrolled in the same class of mine two semesters in a row, and never turned in anything either time.

I’ve been a psychology professor since 2012. In the past six years, I’ve witnessed students of all ages procrastinate on papers, skip presentation days, miss assignments, and let due dates fly by. I’ve seen promising prospective grad students fail to get applications in on time; I’ve watched PhD candidates take months or years revising a single dissertation draft; I once had a student who enrolled in the same class of mine two semesters in a row, and never turned in anything either time.

自 2012 年以来一直担任心理学教授。在过去的六年里,我目睹了各个年龄段的学生拖延论文、跳过演讲日、错过作业和让截止日期飞逝。我见过有前途的准研究生未能按时提交申请;我看到博士生花了几个月或几年的时间来修改一篇论文草稿;我曾经有一个学生连续两个学期报名在我的同一个班级,但两次都没有交过任何东西。

I don’t think laziness was ever at fault.

我不认为懒惰是错的。

Ever. 曾。

In fact, I don’t believe that laziness exists.

事实上,我不相信懒惰存在。

I’m a social psychologist, so I’m interested primarily in the situational and contextual factors that drive human behavior. When you’re seeking to predict or explain a person’s actions, looking at the social norms, and the person’s context, is usually a pretty safe bet. Situational constraints typically predict behavior far better than personality, intelligence, or other individual-level traits.

我是一名社会心理学家,所以我主要对驱动人类行为的情境和背景因素感兴趣。当您试图预测或解释一个人的行为时,查看社会规范和人的背景通常是一个相当安全的选择。情境约束通常比性格、智力或其他个人层面的特征更好地预测行为。

So when I see a student failing to complete assignments, missing deadlines, or not delivering results in other aspects of their life, I’m moved to ask: what are the situational factors holding this student back? What needs are currently not being met? And, when it comes to behavioral “laziness,” I’m especially moved to ask: what are the barriers to action that I can’t see?

因此,当我看到一个学生未能完成作业、错过截止日期或在生活的其他方面没有取得成果时,我很感动地问:是什么情境因素阻碍了这个学生的发展?目前哪些需求没有得到满足?而且,当谈到行为上的“懒惰”时,我特别想问:我看不到的行动障碍是什么?

There are always barriers. Recognizing those barriers— and viewing them as legitimate — is often the first step to breaking “lazy” behavior patterns.

障碍总是存在的。认识到这些障碍——并将它们视为合法的——通常是打破 “懒惰” 行为模式的第一步。

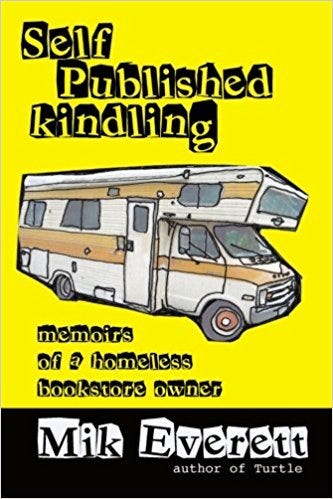

It’s really helpful to respond to a person’s ineffective behavior with curiosity rather than judgment. I learned this from a friend of mine, the writer and activist Kimberly Longhofer (who publishes under the name Mik Everett). Kim is passionate about the acceptance and accommodation of disabled people and homeless people. Their writing about both subjects is some of the most illuminating, bias-busting work I’ve ever encountered. Part of that is because Kim is brilliant, but it’s also because at various points in their life, Kim has been both disabled and homeless.

用好奇心而不是评判来回应一个人的无效行为真的很有帮助。我从我的一个朋友那里了解到这一点,她是作家兼活动家金伯利·朗霍夫(Kimberly Longhofer,他以米克·埃弗雷特(Mik Everett)的名义出版)。Kim 热衷于接受和容纳残疾人和无家可归者。他们关于这两个主题的写作是我遇到过的最有启发性、最消除偏见的作品之一。部分原因是 Kim 很聪明,但也因为在他们生命的不同阶段,Kim 既残疾又无家可归。

Kim is the person who taught me that judging a homeless person for wanting to buy alcohol or cigarettes is utter folly. When you’re homeless, the nights are cold, the world is unfriendly, and everything is painfully uncomfortable. Whether you’re sleeping under a bridge, in a tent, or at a shelter, it’s hard to rest easy. You are likely to have injuries or chronic conditions that bother you persistently, and little access to medical care to deal with it. You probably don’t have much healthy food.

Kim 教会了我,评判一个想买酒或香烟的无家可归者是完全愚蠢的。当你无家可归时,夜晚很冷,世界不友好,一切都令人痛苦地不舒服。无论您是睡在桥下、帐篷里还是避难所,都很难高枕无忧。您可能会有持续困扰您的受伤或慢性病,并且几乎没有机会获得医疗护理来应对这些疾病。你可能没有太多健康的食物。

In that chronically uncomfortable, over-stimulating context, needing a drink or some cigarettes makes fucking sense. As Kim explained to me, if you’re laying out in the freezing cold, drinking some alcohol may be the only way to warm up and get to sleep. If you’re under-nourished, a few smokes may be the only thing that kills the hunger pangs. And if you’re dealing with all this while also fighting an addiction, then yes, sometimes you just need to score whatever will make the withdrawal symptoms go away, so you can survive.

在那种长期不舒服、过度刺激的环境中,需要一杯饮料或一些香烟是他妈的有道理的。正如 Kim 向我解释的那样,如果你躺在寒冷的环境中,喝点酒可能是暖和入睡的唯一方法。如果你营养不良,几根烟可能是唯一能消除饥饿感的东西。如果你在处理这一切的同时也在与成瘾作斗争,那么是的,有时你只需要为任何能使戒断症状消失的东西打分,这样你就可以生存下来。

Kim 的一本令人难以置信的书,讲述了他们在经营书店时无家可归的经历。

Few people who haven’t been homeless think this way. They want to moralize the decisions of poor people, perhaps to comfort themselves about the injustices of the world. For many, it’s easier to think homeless people are, in part, responsible for their suffering than it is to acknowledge the situational factors.

很少有没有无家可归的人会这样想。他们想把穷人的决定道德化,也许是为了安慰自己对世界的不公正。对许多人来说,认为无家可归者对他们的痛苦负有部分责任,比承认情境因素更容易。

And when you don’t fully understand a person’s context — what it feels like to be them every day, all the small annoyances and major traumas that define their life — it’s easy to impose abstract, rigid expectations on a person’s behavior. All homeless people should put down the bottle and get to work. Never mind that most of them have mental health symptoms and physical ailments, and are fighting constantly to be recognized as human. Never mind that they are unable to get a good night’s rest or a nourishing meal for weeks or months on end. Never mind that even in my comfortable, easy life, I can’t go a few days without craving a drink or making an irresponsible purchase. They have to do better.

当你不完全了解一个人的背景时——每天做他们的感受,定义他们生活的所有小烦恼和重大创伤——很容易对一个人的行为施加抽象、僵化的期望。所有无家可归的人都应该放下瓶子开始工作。没关系,他们中的大多数人都有心理健康症状和身体疾病,并且一直在为被认可为人类而奋斗。没关系,他们连续数周或数月无法获得良好的夜间休息或营养餐。没关系,即使在我舒适、轻松的生活中,我也不能几天不渴望喝酒或不负责任地购买。他们必须做得更好。

But they’re already doing the best they can. I’ve known homeless people who worked full-time jobs, and who devoted themselves to the care of other people in their communities. A lot of homeless people have to navigate bureaucracies constantly, interfacing with social workers, case workers, police officers, shelter staff, Medicaid staff, and a slew of charities both well-meaning and condescending. It’s a lot of fucking work to be homeless. And when a homeless or poor person runs out of steam and makes a “bad decision,” there’s a damn good reason for it.

但他们已经在尽其所能了。我认识一些无家可归的人,他们从事全职工作,并致力于照顾社区中的其他人。许多无家可归者不得不不断地在官僚机构中穿梭,与社会工作者、个案工作者、警察、庇护所工作人员、医疗补助工作人员以及一系列善意和居高临下的慈善机构打交道。无家可归真他妈的活很多。当一个无家可归者或穷人耗尽动力并做出“错误的决定”时,这是有充分理由的。

If a person’s behavior doesn’t make sense to you, it is because you are missing a part of their context. It’s that simple. I’m so grateful to Kim and their writing for making me aware of this fact. No psychology class, at any level, taught me that. But now that it is a lens that I have, I find myself applying it to all kinds of behaviors that are mistaken for signs of moral failure — and I’ve yet to find one that can’t be explained and empathized with.

如果一个人的行为对您没有意义,那是因为您错过了他们背景的一部分。就这么简单。我非常感谢 Kim 和他们的写作让我意识到这个事实。任何级别的心理学课都没有教过我这一点。但现在它已成为我拥有的镜头,我发现自己将其应用于各种被误认为道德失败迹象的行为——而我还没有找到无法解释和同情的行为。

Let’s look at a sign of academic “laziness” that I believe is anything but: procrastination.

让我们看看学术界“懒惰”的一个标志,我认为它绝非如此:拖延。

People love to blame procrastinators for their behavior. Putting off work sure looks lazy, to an untrained eye. Even the people who are actively doing the procrastinating can mistake their behavior for laziness. You’re supposed to be doing something, and you’re not doing it — that’s a moral failure right? That means you’re weak-willed, unmotivated, and lazy, doesn’t it?

人们喜欢将自己的行为归咎于拖延者。在未经训练的人看来,推迟工作肯定看起来很懒惰。即使是积极拖延的人也会将他们的行为误认为是懒惰。你应该做某事,但你没有去做——这是道德上的失败,对吧?这意味着你意志薄弱、没有动力和懒惰,不是吗?

For decades, psychological research has been able to explain procrastination as a functioning problem, not a consequence of laziness. When a person fails to begin a project that they care about, it’s typically due to either a) anxiety about their attempts not being “good enough” or b) confusion about what the first steps of the task are. Not laziness. In fact, procrastination is more likely when the task is meaningful and the individual cares about doing it well.

几十年来,心理学研究已经能够将拖延解释为一个功能性问题,而不是懒惰的结果。当一个人未能开始他们关心的项目时,通常是由于 a) 对他们的尝试不够“好”的焦虑或 b) 对任务的第一步感到困惑。不是懒惰。事实上,当任务有意义并且个人关心做好它时,更有可能拖延。

When you’re paralyzed with fear of failure, or you don’t even know how to begin a massive, complicated undertaking, it’s damn hard to get shit done. It has nothing to do with desire, motivation, or moral upstandingness. Procastinators can will themselves to work for hours; they can sit in front of a blank word document, doing nothing else, and torture themselves; they can pile on the guilt again and again — none of it makes initiating the task any easier. In fact, their desire to get the damn thing done may worsen their stress and make starting the task harder.

当你因为害怕失败而瘫痪时,或者你甚至不知道如何开始一项庞大而复杂的任务时,要把狗屎做好就该死的困难了。它与欲望、动机或道德正直无关。Procastinator 可以自己工作数小时;他们可以坐在空白的 word 文档前,什么都不做,折磨自己;他们可以一次又一次地堆积内疚感——这一切都无法使启动任务变得更容易。事实上,他们完成该死的事情的愿望可能会加剧他们的压力,使开始任务变得更加困难。

The solution, instead, is to look for what is holding the procrastinator back. If anxiety is the major barrier, the procrastinator actually needs to walk away from the computer/book/word document and engage in a relaxing activity. Being branded “lazy” by other people is likely to lead to the exact opposite behavior.

相反,解决方案是寻找阻碍拖延者的原因。如果焦虑是主要障碍,那么拖延者实际上需要离开电脑/书籍/word 文档,进行一次放松的活动。被其他人贴上 “懒惰 ”的标签可能会导致完全相反的行为。

Often, though, the barrier is that procrastinators have executive functioning challenges — they struggle to divide a large responsibility into a series of discrete, specific, and ordered tasks. Here’s an example of executive functioning in action: I completed my dissertation (from proposal to data collection to final defense) in a little over a year. I was able to write my dissertation pretty easily and quickly because I knew that I had to a) compile research on the topic, b) outline the paper, c) schedule regular writing periods, and d) chip away at the paper, section by section, day by day, according to a schedule I had pre-determined.

然而,障碍通常是拖延者面临执行功能挑战——他们努力将重大责任划分为一系列离散、具体和有序的任务。这是一个执行功能的实际例子:我在一年多一点的时间里完成了我的论文(从提案到数据收集再到最终答辩)。我能够非常轻松和快速地写出我的论文,因为我知道我必须 a) 整理有关该主题的研究,b) 概述论文,c) 安排定期写作时间,以及 d) 根据我预先确定的时间表,逐节、逐日完成论文。

Nobody had to teach me to slice up tasks like that. And nobody had to force me to adhere to my schedule. Accomplishing tasks like this is consistent with how my analytical, Autistic, hyper-focused brain works. Most people don’t have that ease. They need an external structure to keep them writing — regular writing group meetings with friends, for example — and deadlines set by someone else. When faced with a major, massive project, most people want advice for how to divide it into smaller tasks, and a timeline for completion. In order to track progress, most people require organizational tools, such as a to-do list, calendar, datebook, or syllabus.

没有人需要教我像那样把任务分成几部分。而且没有人必须强迫我遵守我的时间表。完成这样的任务与我的分析性、自闭症、高度专注的大脑的工作方式是一致的。大多数人没有那么轻松。他们需要一个外部结构来保持写作——例如,定期与朋友举行写作小组会议——以及由其他人设定的截止日期。当面临一个重大的大型项目时,大多数人都希望获得有关如何将其划分为较小任务的建议,以及完成时间表的建议。为了跟踪进度,大多数人需要组织工具,例如待办事项列表、日历、日期簿或教学大纲。

Needing or benefiting from such things doesn’t make a person lazy. It just means they have needs. The more we embrace that, the more we can help people thrive.

需要这些东西或从中受益不会使一个人变得懒惰。这只是意味着他们有需求。我们越是接受这一点,就越能帮助人们茁壮成长。

I had a student who was skipping class. Sometimes I’d see her lingering near the building, right before class was about to start, looking tired. Class would start, and she wouldn’t show up. When she was present in class, she was a bit withdrawn; she sat in the back of the room, eyes down, energy low. She contributed during small group work, but never talked during larger class discussions.

我有一个逃课的学生。有时我会看到她在上课前在大楼附近徘徊,看起来很疲惫。上课了,她不会出现。当她在课堂上时,她有点孤僻;她坐在房间的后面,低着头,精力低落。她在小组工作中做出贡献,但在较大的课堂讨论中从不交谈。

A lot of my colleagues would look at this student and think she was lazy, disorganized, or apathetic. I know this because I’ve heard how they talk about under-performing students. There’s often rage and resentment in their words and tone — why won’t this student take my class seriously? Why won’t they make me feel important, interesting, smart?

我的很多同事看着这个学生,会认为她懒惰、杂乱无章或冷漠。我知道这一点,因为我听说他们是如何谈论表现不佳的学生的。他们的言语和语气中经常有愤怒和怨恨——为什么这个学生不认真对待我的课呢?为什么他们不让我觉得自己重要、有趣、聪明呢?

But my class had a unit on mental health stigma. It’s a passion of mine, because I’m a neuroatypical psychologist. I know how unfair my field is to people like me. The class & I talked about the unfair judgments people levy against those with mental illness; how depression is interpreted as laziness, how mood swings are framed as manipulative, how people with “severe” mental illnesses are assumed incompetent or dangerous.

但我的班级有一个关于心理健康耻辱感的单元。这是我的热情所在,因为我是一名神经非典型心理学家。我知道我的领域对像我这样的人有多么不公平。我和班级谈到了人们对精神病患者的不公正判断;抑郁症如何被解释为懒惰,情绪波动如何被描述为操纵性,患有“严重”精神疾病的人如何被认为无能或危险。

The quiet, occasionally-class-skipping student watched this discussion with keen interest. After class, as people filtered out of the room, she hung back and asked to talk to me. And then she disclosed that she had a mental illness and was actively working to treat it. She was busy with therapy and switching medications, and all the side effects that entails. Sometimes, she was not able to leave the house or sit still in a classroom for hours. She didn’t dare tell her other professors that this was why she was missing classes and late, sometimes, on assignments; they’d think she was using her illness as an excuse. But she trusted me to understand.

那个安静的、偶尔逃课的学生饶有兴致地看着这场讨论。下课后,当人们从房间里出来时,她退后了一步,要求和我说话。然后她透露她患有精神疾病,并正在积极努力治疗它。她忙于治疗和更换药物,以及随之而来的所有副作用。有时,她无法离开家或在教室里坐几个小时。她不敢告诉其他教授,这就是她缺课的原因,有时还能迟到作业;他们会认为她是在用自己的疾病作为借口。但她相信我会理解的。

And I did. And I was so, so angry that this student was made to feel responsible for her symptoms. She was balancing a full course load, a part-time job, and ongoing, serious mental health treatment. And she was capable of intuiting her needs and communicating them with others. She was a fucking badass, not a lazy fuck. I told her so.

我做到了。我非常非常生气,以至于这个学生觉得自己要为自己的症状负责。她正在平衡满负荷的课程负担、一份兼职工作和正在进行的、严重的心理健康治疗。她能够直觉地了解自己的需求并与他人沟通。她是个他妈的坏蛋,而不是一个懒惰的他妈的。我告诉她。

She took many more classes with me after that, and I saw her slowly come out of her shell. By her Junior and Senior years, she was an active, frank contributor to class — she even decided to talk openly with her peers about her mental illness. During class discussions, she challenged me and asked excellent, probing questions. She shared tons of media and current-events examples of psychological phenomena with us. When she was having a bad day, she told me, and I let her miss class. Other professors — including ones in the psychology department — remained judgmental towards her, but in an environment where her barriers were recognized and legitimized, she thrived.

在那之后,她和我一起上了很多课,我看到她慢慢地走出了自己的壳。到了初中和高中,她是一个积极、坦率的课堂贡献者——她甚至决定与同龄人公开谈论她的精神疾病。在课堂讨论中,她向我提出挑战,并提出了出色的探索性问题。她与我们分享了大量媒体和时事的心理现象例子。当她今天过得不好时,她告诉我,我让她缺课。其他教授——包括心理学系的教授——仍然对她评判,但在一个她的障碍得到认可和合法化的环境中,她茁壮成长。

照片由 Janos Richter 提供,由 Unsplash 提供

Over the years, at that same school, I encountered countless other students who were under-estimated because the barriers in their lives were not seen as legitimate. There was the young man with OCD who always came to class late, because his compulsions sometimes left him stuck in place for a few moments. There was the survivor of an abusive relationship, who was processing her trauma in therapy appointments right before my class each week. There was the young woman who had been assaulted by a peer — and who had to continue attending classes with that peer, while the school was investigating the case.

多年来,在同一所学校,我遇到了无数其他被低估的学生,因为他们生活中的障碍不被视为合法的。有个患有强迫症的年轻人,他总是迟到,因为他的强迫症有时会让他在原地呆一会儿。有一位虐待关系的幸存者,她每周在我上课前的治疗预约中处理她的创伤。有一名年轻女子被一名同龄人性侵——在学校调查此案期间,她不得不继续与那名同龄人一起上课。

These students all came to me willingly, and shared what was bothering them. Because I discussed mental illness, trauma, and stigma in my class, they knew I would be understanding. And with some accommodations, they blossomed academically. They gained confidence, made attempts at assignments that intimidated them, raised their grades, started considering graduate school and internships. I always found myself admiring them. When I was a college student, I was nowhere near as self-aware. I hadn’t even begun my lifelong project of learning to ask for help.

这些学生都自愿来找我,分享困扰他们的事情。因为我在课堂上讨论了精神疾病、创伤和耻辱感,所以他们知道我会理解。通过一些住宿,他们在学业上取得了成果。他们获得了信心,尝试了让他们生畏的作业,提高了成绩,开始考虑研究生院和实习。我总是发现自己很欣赏他们。当我还是一名大学生时,我的自我意识远没有那么强。我什至还没有开始我一生的学习寻求帮助的项目。

Students with barriers were not always treated with such kindness by my fellow psychology professors. One colleague, in particular, was infamous for providing no make-up exams and allowing no late arrivals. No matter a student’s situation, she was unflinchingly rigid in her requirements. No barrier was insurmountable, in her mind; no limitation was acceptable. People floundered in her class. They felt shame about their sexual assault histories, their anxiety symptoms, their depressive episodes. When a student who did poorly in her classes performed well in mine, she was suspicious.

我的心理学教授同事并不总是如此善待有障碍的学生。特别是一位同事,因为不提供补考和不允许迟到而臭名昭著。无论学生的情况如何,她都坚定不移地严格要求自己。在她心中,没有什么是不可逾越的障碍;没有限制是可以接受的。人们在她的课堂上挣扎。他们对自己的性侵犯历史、焦虑症状、抑郁发作感到羞耻。当一个学生在她的班级里表现不佳时,她很怀疑。

It’s morally repugnant to me that any educator would be so hostile to the people they are supposed to serve. It’s especially infuriating, that the person enacting this terror was a psychologist. The injustice and ignorance of it leaves me teary every time I discuss it. It’s a common attitude in many educational circles, but no student deserves to encounter it.

在道德上,任何教育工作者都会对他们应该服务的人如此敌视,这在道德上是令人反感的。尤其令人愤怒的是,实施这种恐怖的人是一名心理学家。每次讨论它时,它的不公正和无知都让我泪流满面。这是许多教育界的普遍态度,但没有学生应该遇到它。

I know, of course, that educators are not taught to reflect on what their students’ unseen barriers are. Some universities pride themselves on refusing to accommodate disabled or mentally ill students — they mistake cruelty for intellectual rigor. And, since most professors are people who succeeded academically with ease, they have trouble taking the perspective of someone with executive functioning struggles, sensory overloads, depression, self-harm histories, addictions, or eating disorders. I can see the external factors that lead to these problems. Just as I know that “lazy” behavior is not an active choice, I know that judgmental, elitist attitudes are typically borne out of situational ignorance.

当然,我知道教育工作者没有被教导去反思他们的学生看不见的障碍是什么。一些大学以拒绝接收残疾或精神病学生而自豪——他们把残酷误认为是知识的严谨。而且,由于大多数教授都是在学术上轻松成功的人,因此他们很难从执行功能困难、感觉超负荷、抑郁、自残史、成瘾或饮食失调的人的角度看待。我可以看到导致这些问题的外部因素。正如我知道“懒惰”行为不是一个主动的选择一样,我知道评判性的精英主义态度通常是出于情境无知。

And that’s why I’m writing this piece. I’m hoping to awaken my fellow educators — of all levels — to the fact that if a student is struggling, they probably aren’t choosing to. They probably want to do well. They probably are trying. More broadly, I want all people to take a curious and empathic approach to individuals whom they initially want to judge as “lazy” or irresponsible.

这就是我写这篇文章的原因。我希望唤醒我的各个级别的教育工作者,让他们意识到,如果学生正在挣扎,他们可能不会选择这样做。他们可能想做得好。他们可能正在尝试。更广泛地说,我希望所有人都能对他们最初想判断为“懒惰”或不负责任的人采取好奇和同理心的方法。

If a person can’t get out of bed, something is making them exhausted. If a student isn’t writing papers, there’s some aspect of the assignment that they can’t do without help. If an employee misses deadlines constantly, something is making organization and deadline-meeting difficult. Even if a person is actively choosing to self-sabotage, there’s a reason for it — some fear they’re working through, some need not being met, a lack of self-esteem being expressed.

如果一个人无法下床,那么有什么事情让他们筋疲力尽。如果学生不写论文,那么作业的某些方面是他们没有帮助就无法完成的。如果员工经常错过截止日期,就会使组织和截止日期难以实现。即使一个人主动选择自我破坏,也是有原因的——有些人担心他们正在努力克服,有些人不需要得到满足,缺乏自尊被表达出来。

People do not choose to fail or disappoint. No one wants to feel incapable, apathetic, or ineffective. If you look at a person’s action (or inaction) and see only laziness, you are missing key details. There is always an explanation. There are always barriers. Just because you can’t see them, or don’t view them as legitimate, doesn’t mean they’re not there. Look harder.

人们不会选择失败或失望。没有人愿意感到无能、冷漠或无能为力。如果你看一个人的行动(或不作为),只看到懒惰,你就错过了关键细节。总有解释的。障碍总是存在的。仅仅因为你看不到它们,或者不认为它们是合法的,并不意味着它们不存在。更仔细地看。

Maybe you weren’t always able to look at human behavior this way. That’s okay. Now you are. Give it a try.

也许你并不总是能够以这种方式看待人类行为。没关系。现在你是。试一试。

If you found this essay illuminating at all, please consider buying Kim Longhofer / Mik Everett’s book, Self-Published Kindling: Memoirs of a Homeless Bookstore Owner. The ebook is $3; the paperback is $15.

如果您觉得这篇文章很有启发性,请考虑购买 Kim Longhofer / Mik Everett 的书, 自行出版的火种:无家可归书店老板的回忆录.电子书是 3 美元;平装本是 15 美元。

Kim also runs a fat-positive, cripplepunk page called Change Like the Moon: Accept Every Body at Every Phase.

Kim 还运营着一个积极肥胖的瘸子朋克页面,名为 Change Like the Moon: Accept Every Body at Every Phase。