Jeep’s China EV Partner Could Drag It Into a Trade War

Stellantis is walking a regulatory tightrope to fulfill its ambitions in the world’s biggest car market.

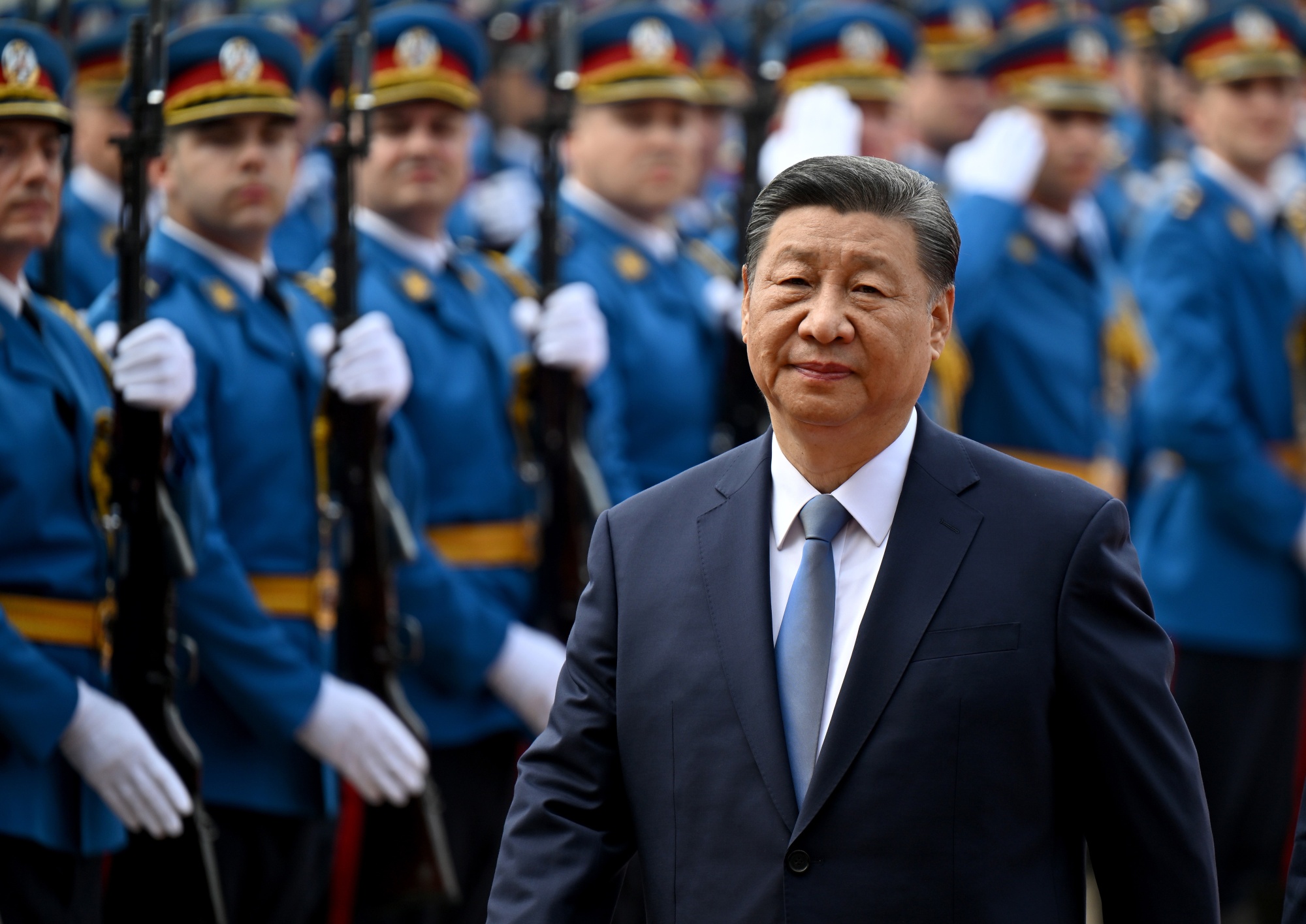

A delicate relationship.

Photographer: Future Publishing/Getty Images

The US and China’s once simmering trade war over clean technology has now reached fever pitch. Just have a listen.

Chinese-made vehicles on US roads could potentially “be immediately and simultaneously disabled by somebody in Beijing,” Commerce Secretary Gina Raimondo speculated earlier this year. Beijing’s economic policy is predicated on “hollowing out our industrial base,” Brian Deese, former director of President Joe Biden’s National Economic Council, fretted April 25.

You don’t have to believe those panicky views to think Western companies venturing into China amid this gathering storm would do well to carry an umbrella. Stellantis NV, the owner of the Jeep, Chrysler, Maserati and Peugeot brands, has failed to heed that lesson.

Last October, Chief Executive Officer Carlos Tavares made a play to solve its late start to electrification and its vestigial presence in China with one bold stroke. He spent €1.5 billion ($1.6 billion) buying about a fifth of fast-growing EV company Zhejiang Leapmotor Technology Co. The deal gives Stellantis exclusive rights to distribute and potentially manufacture Leapmotor’s cars outside China, plus a stake in its home market.

It also leaves Tavares perched on a daunting regulatory tightrope he may come to regret.

The Leapmotor deal was necessary, he argued at the time, because automakers in China had the technological edge and could build battery cars 30% cheaper. Western companies that failed to team up would struggle. “We do not intend to be on the defensive,” he said. “We are part of the Chinese offensive.”

That warlike metaphor seems an unfortunate one, given that Leapmotor shares its founders, key shareholders and outsourcing contracts with a surveillance-camera business the US designates a Chinese military company.

Its billionaire founders Fu Liquan and Zhu Jiangming spent decades building Zhejiang Dahua Technology Co., or Dahua, into the world’s second-largest maker of CCTVs, intercoms and the like. They reinvested their wealth from that business to start Leapmotor in 2015 along with their wives and colleagues.

Dahua’s extensive contracts in the world’s biggest surveillance state, and the ability of its products to be used in military applications, have landed it in hot water on multiple continents.

According to a 2019 US sanctions update, it was among companies “implicated in human rights violations and abuses in the implementation of China's campaign of repression, mass arbitrary detention, and high-technology surveillance” in Xinjiang, where members of Muslim minority groups have been targeted. One of its facial-recognition software products has shipped with search filters to detect people’s race, while product support documents have offered the ability to send alerts if people from the Uighur minority are spotted, according to a 2021 Los Angeles Times investigation. Its cameras are banned from government sites in the UK and Australia and from all public-security uses in the US. Ukraine’s government has listed Dahua as a “war sponsor” supporting Russia’s invasion1.

It might have been considered prudent for Leapmotor to put the greatest distance possible between itself and this business. That hasn’t happened, however. Fu and Zhu remain the largest shareholders of both companies via jointly controlled family stakes. The firm also outsources the assembly of circuit boards and procures cameras and radar devices from Dahua subsidiaries, and many of its senior executives and engineers are former employees of the camera business.

Spokespeople for Leapmotor and Dahua didn’t respond to more than half-a-dozen emails, phone calls and text messages seeking comment. A Stellantis spokesman said by e-mail that the company and Leapmotor “will always abide by all laws and regulations in the regions where the companies operate.”

On paper, there’s no imminent risk in the relationship. It’s “not the case that the restrictions on Dahua bleed over to Leapmotor; Leapmotor itself would have to be named” in a sanctions filing, Paul D. Marquardt, head of the national security practice at law firm Davis Polk, said by email from Washington.

Acting primarily as an overseas distribution arm and passive equity investor in China also helps Stellantis avoid protectionist tangles. There’s been no suggestion of Leapmotor-sourced components going into products for the North American market.

Still, it’s unlikely that a purchase of a minority stake at a 19% premium to market is going to end here, especially given Tavares’ interest in Leapmotor’s cost advantages. Stellantis might look at joint purchasing or manufacturing deals to get around trade restrictions, Chief Financial Officer Natalie Knight told investors Nov. 1. It’s already working on a plan to assemble Leapmotor’s T03 mini-car for the European market in Poland, Reuters reported in March citing two sources it didn’t name.

As I’ve argued, Washington’s protectionist hostility to Chinese technological leadership in EVs relies on bad economics and mistaken history lessons, and may impoverish the non-Chinese auto industry while ignoring the homegrown problems for US clean tech. Still, it’s not necessary to believe there’s anything nefarious about Leapmotor’s relationship with Dahua to see why the company is an odd choice of partner.

Recognizing that not every Chinese firm is a security risk, after all, requires accepting that some of them might be — and that others have connections that, at the very least, might become regulatory and political risks, at a time when US-China trade tensions are constantly ratcheting up. A marginal widening of existing sanctions instruments, or a campaign by an ambitious lawmaker, is all that would be required to make the association a liability for Stellantis in North America.

That region accounts for about half of its revenue and profits, and the Biden administration seems determined to make it a Chinese car-free zone. The US has pressured Mexico to thwart China’s carmakers looking to set up south of the border, and is investigating whether vehicles using cameras and sensors from China “could be exploited in ways that threaten national security.” That’s likely to limit the ways Stellantis can collaborate with a Chinese partner which buys sensors from a sanctioned military company founded and part-owned by its own CEO. Donald Trump, meanwhile, has promised a 100% tariff on Chinese-made cars if elected.

Stellantis is wise to build close ties with China’s formidable manufacturing sector to ride the coming wave of electrification, especially after bitter break-ups with its previous partners Guangzhou Automobile Group and Dongfeng Motor Group Co. There are plenty of businesses out there, however, without the associations that make Leapmotor such a prickly prospect.

The automotive industry has always been bound up with national identity. Right now, the US is drifting toward a Reds-under-the-bed scare around Chinese clean-technology leadership, on a scale rarely seen since the Cold War. Should that fear shift to worries that the Reds are under the hood of your Jeep, too, Tavares might wish he’d picked another partner.

More From Bloomberg Opinion:

- The White House Has a New Trade Weapon Against China: Liam Denning

- Yellen Junks 200 Years of Economics to Block China Clean Tech: David Fickling

- Tennessee’s Union Vote Is a Symbol of the New South: Mary Ellen Klas

Want more Bloomberg Opinion? Head to OPIN <GO>. Or you can subscribe to our daily newsletter.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.