On Being with Krista Tippett

与克里斯塔-蒂佩特共勉

Alain de Botton

阿兰-德波顿

The True Hard Work of Love and Relationships

爱与关系的真正艰辛

As people, and as a culture, Alain de Botton says, we would be much saner and happier if we reexamined our very view of love. His New York Times essay, “Why You Will Marry the Wrong Person,” is one of their most-read articles in recent years, and this is one of the most popular episodes we’ve ever created. We offer up the anchoring truths he shares amidst a pandemic that has stretched all of our sanity — and tested the mettle of love in every relationship.

阿兰-德波顿说,作为一个人,作为一种文化,如果我们重新审视自己的爱情观,我们就会理智得多,幸福得多。他在《纽约时报》上发表的文章《为什么你会嫁错人》是近年来阅读量最高的文章之一,这也是我们制作的最受欢迎的节目之一。我们将为您提供他所分享的箴言,这些箴言让我们所有人的理智都受到了考验,也考验了每段关系中爱情的坚韧度。

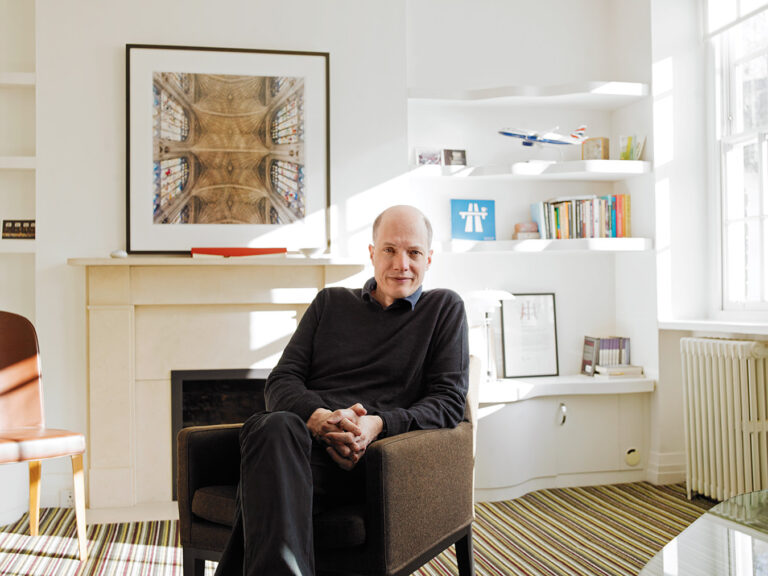

Image by Victoria Birkinshaw, © All Rights Reserved.

图片由 Victoria Birkinshaw 提供,版权所有。

Guest

游客

Alain de Botton is the founder and chairman of The School of Life. His books include Religion for Atheists and How Proust Can Change Your Life. He’s also published many books as part of The School of Life’s offerings, including a chapbook created from his essay Why You Will Marry the Wrong Person.

阿兰-德波顿是生命学院的创始人和主席。他的著作包括《无神论者的宗教》和《普鲁斯特如何改变你的生活》。他还出版了许多书籍,作为生命学院产品的一部分,其中包括一本根据他的散文《为什么你会嫁错人》创作的小册子。

Transcript

文字稿

Krista Tippett, host:

Krista Tippett,主持人: Alain de Botton’s essay “Why You Will Marry the Wrong Person” is one of the most-read articles in The New York Times of recent years, and this is one of the most popular episodes we’ve ever created. As people and as a culture, he says, we would be much saner and happier if we reexamined our very view of love. I’m glad to offer up the anchoring truths he tells amidst a pandemic that has stretched all of our sanity — and tested the mettle of love in every home and relationship.

阿兰-德波顿的文章《为什么你会嫁错人》是近年来《纽约时报》上阅读量最高的文章之一,这也是我们制作的最受欢迎的节目之一。他说,作为一个人和一种文化,如果我们重新审视自己的爱情观,我们会变得更理智、更幸福。我很高兴能提供他所讲述的锚定真理,在这场大流行中,我们所有人的理智都受到了挑战,每个家庭和关系中的爱都经受住了考验。

Alain de Botton:

阿兰-德波顿 Love is something we have to learn and we can make progress with, and that it’s not just an enthusiasm, it’s a skill. And it requires forbearance, generosity, imagination, and a million things besides. The course of true love is rocky and bumpy at the best of times, and the more generous we can be towards that flawed humanity, the better chance we’ll have of doing the true hard work of love.

爱是我们必须学会的东西,也是我们可以取得进步的东西,它不仅仅是一种热情,更是一种技能。它需要宽容、大度、想象力,以及无数其他的东西。真爱的道路在最好的情况下也是坎坷不平的,我们对有缺陷的人性越宽容,就越有机会完成爱的真正艰巨的工作。

Tippett:

蒂皮特I’m Krista Tippett, and this is On Being.

我是克里斯塔-蒂佩特,这里是《论存在》。

[music: “Seven League Boots” by Zoe Keating]

[音乐: 佐伊-基廷的 "七连靴"]

Alain de Botton is the founder and chairman of The School of Life, a gathering of courses, workshops, and talks on meaning and wisdom for modern lives, with branches around the world. He first became known for his book How Proust Can Change Your Life. I spoke with him in 2017.

阿兰-德波顿是 "生命学院 "的创始人和主席。"生命学院 "的课程、工作坊和讲座涉及现代生活的意义和智慧,其分支机构遍布世界各地。他最初因《普鲁斯特如何改变你的生活》一书而闻名。我曾在2017年与他交谈过。

Tippett:

蒂皮特 So we did speak a few years ago, but on a very different topic, and I’m really excited to be speaking with you about this subject, which is so close to every life. And as I’ve prepared for this, I realize that you’ve actually — I knew that you’d written the novel On Love a long time ago, but you’ve really been consistently attending to this subject and building your thoughts on it and your body of work on it, which is really interesting to me. You wrote On Love at the age of 23, which is so young, and you were already thinking about this so deeply. I think this is the first line: “Every fall into love involves the triumph of hope over knowledge.”

几年前,我们曾有过一次交谈,但主题截然不同,我真的很高兴能与你谈论这个与每个人生活都息息相关的话题。在我准备这个话题的过程中,我意识到你其实--我知道你很久以前就写了小说《论爱》,但你真的一直在关注这个话题,并在此基础上形成了自己的思想和作品,这对我来说真的很有趣。你在 23 岁时就写出了《论爱》,这是多么年轻的年纪,而你却已经对这个问题有了如此深刻的思考。我认为这是第一行:"每一次坠入爱河 都是希望战胜了知识"

de Botton:

德波顿 Well, and I think what’s striking is that our idea of what love is, our idea of what is normal in love, is so not normal.

嗯,我觉得令人震惊的是,我们对爱情的理解,我们对爱情中正常情况的理解,都太不正常了。

Tippett:

蒂皮特 Is so abnormal. Right.

太不正常了对

de Botton:

德波顿 So abnormal. And so we castigate ourselves for not having a normal love life, even though no one seems to have any of these.

太不正常了。因此,我们责备自己没有正常的爱情生活,尽管似乎没有人拥有这些。

Tippett:

蒂皮特 Or not have been loved perfectly.

或者没有被完美地爱过。

de Botton:

德波顿 Right, right. So we have this ideal of what love is and then these very, very unhelpful narratives of love. And they’re everywhere. They’re in movies and songs — and we mustn’t blame songs and movies too much. But if you say to people, “Look, love is a painful, poignant, touching attempt by two flawed individuals to try and meet each other’s needs in situations of gross uncertainty and ignorance about who they are and who the other person is, but we’re going to do our best,” that’s a much more generous starting point. So the acceptance of ourselves as flawed creatures seems to me what love really is. Love is at its most necessary when we are weak, when we feel incomplete, and we must show love to one another at those points. So we’ve got these two contrasting stories, and we get them muddled.

对,没错所以我们对爱有这样的理想 然后对爱有这些非常非常无益的叙述它们无处不在它们出现在电影和歌曲中--我们不能过多地指责歌曲和电影。但如果你对人们说:"听着,爱情是两个有缺陷的人在对自己是谁和对方是谁严重不确定和无知的情况下,试图满足对方需求的一种痛苦、凄美、感人的尝试,但我们会尽最大努力。因此,在我看来,接受自己是有缺陷的生物才是真正的爱。当我们软弱,当我们感到不完整时,爱是最有必要的,我们必须在这些时候向彼此表达爱。因此,我们就有了这两个截然不同的故事,而我们却把它们弄混了。

Tippett:

蒂皮特 And also, I feel like this should be obvious, but you just touched on art and culture and how that could help us complexify our understanding of this. And one of the things you point out about — I don’t know; When Harry Met Sally or Four Weddings and a Funeral — one of the things that’s wrong with all of that is that a lot of these take us up to the wedding. They take us through the falling and don’t see that — I think you’ve written somewhere — you said, “A wiser culture than ours would recognize that the start of a relationship is not the high point that romantic art assumes; it is merely the first step of a far longer, more ambivalent, and yet quietly audacious journey on which we should direct our intelligence and scrutiny.” [laughs]

还有,我觉得这应该是显而易见的,但你刚才提到了艺术和文化,以及它们如何帮助我们复杂地理解这一点。你指出的其中一件事--我不知道;《当哈利遇见莎莉》或《四个婚礼和一个葬礼》--所有这些作品的一个问题是,很多作品都把我们带到了婚礼上。他们把我们带入坠落的过程,却没有看到--我想你在什么地方写过--你说过,"比我们更明智的文化会认识到,一段关系的开始并不是浪漫艺术所假定的高潮;它只是一段更漫长、更矛盾、却又悄无声息的大胆旅程的第一步,我们应该把我们的智慧和审视投向这段旅程"。[笑]

de Botton:

德波顿 That’s right. We are strangely obsessed by the run-up to love. And what we call a love story is really just the beginning of a love story, but we leave that out. But most of us, we’re interested in long-term relationships. We’re not just interested in the moment that gets us into love; we’re interested in the survival of love over time.

没错。我们奇怪地沉迷于爱情的前奏。我们所谓的爱情故事 其实只是爱情故事的开端 但我们忽略了这一点但我们大多数人都对长期关系感兴趣我们感兴趣的不仅仅是让我们坠入爱河的那一刻,我们感兴趣的是爱情的长期存在。

Tippett:

蒂皮特 A lot of what you are pointing at, the work of loving over a long span of time, is inner work, right? [laughs] And it would be hard to film that. But I’m very intrigued by how you talk about the Ancient Greeks and their “pedagogical” view of love.

你说的很多东西,长期的爱的工作,都是内心的工作,对吗?[笑]这很难拍成电影。但我对你谈到的古希腊人和他们的 "教学式 "爱情观很感兴趣。

de Botton:

德波顿 That’s fascinating, because one of the greatest insults that you can level at a lover in the modern world, apparently, is to say, “I want to change you.” The Ancient Greeks had a view of love which was essentially based around education; that what love means — love is a benevolent process whereby two people try to teach each other how to become the best versions of themselves.

这很吸引人,因为在现代社会中,对爱人最大的侮辱之一 显然就是说 "我想改变你"。古希腊人的爱情观本质上是以教育为基础的;爱情的含义--爱情是一个仁慈的过程,两个人试图通过这个过程教会对方如何成为最好的自己。

Tippett:

蒂皮特 You say somewhere, they are committed to “increasing the admirable characteristics” that they possess and the other person possesses.

你说在某处,他们致力于 "增加 "自己和对方所拥有的 "令人钦佩的特点"。

de Botton:

德波顿 That’s right. That’s right.

这就对了没错

Tippett:

蒂皮特 Your most recent book on this subject is The Course of Love, which is a novel, but it’s a novel that actually, I feel, you kind of weave a pedagogical narrator voice into it. Do you think that’s fair?

你最近一本关于这个主题的书是《爱的历程》,这是一本小说,但我觉得,你在小说中编织了一种教学叙述者的声音。你觉得这样公平吗?

de Botton:

德波顿 That’s right. Absolutely.

这就对了。没错

Tippett:

蒂皮特 Woven into the narrative. And you say, at one point, this is the relationship between Rabih and Kirsten. And you said at one point, “Their relationship is secretly yet mutually marked by a project of improvement,” which I think we all recognize. And then there’s this moment where you say, “After the dinner party, Rabih is sincerely trying to bring about an evolution in the personality of the wife he loves. But his chosen technique is distinctive: to call Kirsten materialistic, to shout at her, and then, later, to slam two doors.” [laughs]

编织在叙事中你曾说过,这是拉比和克尔斯滕之间的关系。你曾说过,"他们的关系暗中却又相互烙印着一个改进的计划",我想我们都认识到了这一点。然后你又说:"在晚宴之后,拉比真诚地试图让他所爱的妻子的个性发生转变。但他选择的方式很特别:说克尔斯滕是物质主义者,对她大喊大叫,后来还摔了两扇门"。[笑]

de Botton:

德波顿 That’s right.

这就对了。

Tippett:

蒂皮特 And we all recognize that scene. [laughs]

我们都认识那一幕[笑]

de Botton:

德波顿 [laughs] By the time we’ve humiliated someone, they’re not going to learn anything. The only conditions — as we know with children, the only conditions under which anyone learns are conditions of incredible sweetness, tenderness, patience — that’s how we learn. But the problem is that the failures of our relationships have made us so anxious that we can’t be the teachers we should be. And therefore, some often genuine, legitimate things that we want to get across are just — come across as insults, as attempts to wound, and are therefore rejected, and the arteries of the relationship start to fur.

[笑] 当我们羞辱一个人的时候,他就什么也学不会了。唯一的条件--正如我们对孩子所了解的那样,任何人学习的唯一条件就是令人难以置信的甜蜜、温柔和耐心--这才是我们学习的方式。但问题是,人际关系的失败让我们如此焦虑,以至于我们无法成为我们应该成为的老师。因此,我们想要表达的一些真正的、合理的东西就被当成了侮辱,当成了伤人的企图,因此遭到了拒绝,关系的动脉开始断裂。

Tippett:

蒂皮特 Someone recently said to me — and I’d be curious about how you would respond to this. It was a wise Jewish mother who had said to them, “Men marry women with the intention that they — with the idea that they will the stay the same. Women marry men with the idea that they will change.” Which is obviously a huge generalization, but gosh, it made a lot of sense to me, even in terms of my own life and in terms of what I see around me.

最近有人对我说--我很好奇你们会如何回应。是一位睿智的犹太母亲对他们说的:"男人娶女人的目的是希望她们--希望她们保持不变。而女人嫁给男人则是希望他们能改变"。这显然是一个很大的概括,但是天哪,这对我来说很有意义,甚至对我自己的生活和我周围所看到的都很有意义。

de Botton:

德波顿 I would argue that both genders want to change one another, and they both have an idea of who the lover “should” be. And I think a useful exercise that sometimes psychologists level at feuding couples is they say things like, “If you could accept that your partner would never change, how would you feel about that?”

我想说的是,两性都想改变对方,都有一个爱人 "应该 "是什么样的想法。我认为心理学家有时会对不和的情侣做一个有用的练习 他们会说 "如果你能接受你的伴侣永远不会改变 你会有什么感觉?"

Sometimes pessimism, a certain degree of pessimism can be a friend of love. Once we accept that actually it’s really very hard for people to be another way, we’re sometimes readier. We don’t need people to be perfect, is the good news. We just need people to be able to explain their imperfections to us in good time, before they’ve hurt us too much with them, and with a certain degree of humility. That’s already an enormous step.

有时候,悲观,某种程度的悲观可以成为爱的朋友。一旦我们接受了这样的事实,即人真的很难变成另一种样子,我们有时就会变得更坦然。好消息是,我们并不需要人们完美无缺。我们只需要人们能够及时向我们解释他们的不完美之处,在他们用不完美伤害我们太多之前,并带着一定程度的谦卑。这已经是很大的进步了。

Tippett:

蒂皮特 It’s a lot to ask, but it’s so — it’s also — it sounds reasonable, if we could really have that in our minds early enough on in a relationship.

这个要求很高,但如果我们真的能在恋爱初期就有这样的想法,这听起来也很合理。

de Botton:

德波顿 That’s right, and almost from the first date. My view of what one should talk about on a first date is not showing off and not putting forward one’s accomplishments, but almost quite the opposite. One should say, “Well, how are you crazy? I’m crazy like this.” [Editor’s note: Since this interview was recorded, the word “crazy” has fallen out of use as sensitivity to people who live with mental illness has grown.] And there should be a mutual acceptance that two damaged people are trying to get together, because pretty much all of us — there are a few totally healthy people — but pretty much all of us reach dating age with some scars, some wounds.

没错,而且几乎是从第一次约会开始。在我看来,第一次约会应该谈论的话题不是炫耀,也不是炫耀自己的成就,而几乎恰恰相反。应该说 "你怎么这么疯狂?我就是这样疯的。"[编者注:自这次采访录制以来,随着人们对精神疾病患者的关注度越来越高,"疯了 "这个词已经不再使用了。]我们应该相互承认,两个受到伤害的人正试图走到一起,因为我们几乎所有人--也有少数完全健康的人--但几乎所有人到了谈婚论嫁的年龄都带着一些伤疤、一些伤口。

And sometimes we bring to adult relationships some of the same hope that a young child might’ve had of their parent. And of course, an adult relationship can’t be like that. It’s got to accept that the person across the table or on the other side of the bed is just human, which means full of flaws, fears, etc., and not some sort of superhuman.

有时,我们会把小孩子对父母的希望带到成人关系中。当然,成人关系不能这样。我们必须承认,桌子对面或床另一边的那个人也是人,也就是充满了缺陷、恐惧等,而不是什么超人。

Tippett:

蒂皮特 And I think that that question that you said could be a standard question on an early date — “And how are you crazy?” — there’s also something that you’re getting at that it almost seems like we must be hardwired to do this, although one of the wonderful things we’re learning in the 21st century is that we can change our brains. But a way you say it in On Love, in a scene in On Love, is, you start to be enamored in details of this new person and find things in common like, I don’t know, “both of us had two large freckles on the toe of the left foot,” [laughs] and then, you wrote, “Instinctively” — and this happens very quickly — “he teases out an entire personality from the details.”

我觉得你说的那个问题可能是早期约会时的一个标准问题--"你是怎么疯的?"--你还提到了一些东西,似乎我们必须天生就这样做,尽管我们在21世纪学到的一件奇妙的事情是,我们可以改变我们的大脑。但你在《论爱》中的一个场景是这样说的:你开始对这个新人的细节着迷,发现了一些共同点,比如,我不知道,"我们左脚脚趾上都有两个大雀斑",[笑]然后,你写道,"本能地"--这发生得非常快--"他从细节中挖掘出了一个完整的人格"。

But also, what I know from my own life is you tend to — when we fall in love with another person, we magnify in our minds those things that are immediately enrapturing and craft our idea of the other person almost exclusively around those wonderful qualities, which is not fair to them or to us. [laughs]

但同时,我从自己的生活中体会到的是,当我们爱上另一个人的时候,我们往往会在脑海中放大那些立即让人着迷的东西,并几乎完全围绕着这些美好的品质来塑造我们对对方的印象,这对他们和我们都不公平。[笑]

de Botton:

德波顿 That’s right. And we feel, in a way, that we know them already, and we impose on them an idea —

这就对了。我们觉得,在某种程度上,我们已经了解他们了,我们把一种想法强加给他们--

Tippett:

蒂皮特 And of course, we don’t. Right.

当然,我们没有。好吧

de Botton:

德波顿 And we don’t. We don’t. Which also explains another phenomenon that I’m fascinated by — you probably will have noticed in both novels — is the phenomenon of being in a sulk; of sulking, because sulking is a fascinating situation which takes you right into the heart of certain romantic delusions. Because what’s fascinating about sulking is that we don’t sulk with everybody. We only get into sulks with people that we feel should understand us but, rather unforgivably, haven’t understood us.

而我们没有。我们没有。这也解释了另一个我着迷的现象--你可能在两本小说中都注意到了--那就是生闷气的现象;生闷气,因为生闷气是一种迷人的情况,它带你进入某些浪漫妄想的核心。因为生闷气的迷人之处在于,我们不会对所有人都生闷气。我们只和那些我们觉得应该理解我们,但却不理解我们的人生闷气。

So in other words, it’s when we are in love with people and they’re in love with us that we take particular offense when they get things wrong. Because the kind of the governing assumption of the relationship is, this person should know what’s in my mind, ideally without me needing to tell them. If I need to spell this out to you, you don’t love me.

换句话说,当我们爱上一个人,而对方也爱着我们的时候,我们就会在对方出错的时候特别生气。因为这种关系的基本假设是,这个人应该知道我在想什么,最好是不需要我告诉他。如果我需要向你说明这些,那你就不爱我。

And that’s why you’ll go into the bathroom, bolt the door, and when your partner says, “Is anything wrong?” You’ll go, “Mm-mm.” And the reason is that they should be able to read through the bathroom panel into your soul and know what’s wrong. And that’s such an extraordinary demand.

这就是为什么你会走进浴室 把门闩上 当你的伴侣问 "有什么不对吗?"你会说 "嗯"原因是他们应该能透过浴室的门板 读到你的灵魂深处 知道你出了什么问题这是一个非同寻常的要求

Tippett:

蒂皮特 It’s so unfair. [laughs]

这太不公平了[笑]

de Botton:

德波顿 We see it in children. This is how little children behave. They literally think that their parents can read their minds. It takes a long time to realize that the only way that one person can really learn about another is if it’s explained to them, preferably using words, quite calm ones.

我们在孩子身上就能看到。这就是小孩子的表现。他们真的以为父母可以读懂他们的心思。要花很长时间才能认识到,一个人真正了解另一个人的唯一途径是向他们解释,最好是用语言,非常平和的语言。

Tippett:

蒂皮特 Yes, “use your words,” [laughs] which we say to children.

是的,"用你的语言",[笑]这是我们对孩子们说的话。

de Botton:

德波顿 [laughs] When people always say, “Communicate,” we have to be generous towards the reasons why we don’t. And we don’t because we’re operating with this mad idea that true love means intuitive understanding. And I go crazy when people say things like, “I met someone. The loveliest thing is, they understood me without me needing to speak.”

[当人们总是说 "沟通 "的时候,我们必须对我们不沟通的原因慷慨解囊。我们不沟通,是因为我们有一种疯狂的想法,认为真爱意味着直观的理解。当人们说 "我遇到了一个人。"最可爱的是 我不需要说话 他们就能理解我"

Tippett:

蒂皮特 [laughs] Right.

对

de Botton:

德波顿 So many alarm bells go off when I hear that, because I think, OK, well, good luck in this instance, but if you guys get together, that’s not going to go on forever. No one can intuitively understand another beyond a quite limited range of topics.

当我听到这句话的时候,我的心里就会敲响很多警钟,因为我会想,好吧,这次祝你们好运,但如果你们在一起,那也不会永远在一起。除了有限的话题之外,没有人能凭直觉理解别人。

Tippett:

蒂皮特 Your children — how old are your children? They’re still pretty young, right?

您的孩子--您的孩子多大了?他们还很小吧?

de Botton:

德波顿 They’re 10 and 12.

他们分别是 10 岁和 12 岁。

Tippett:

蒂皮特 Oh, OK. So now that I have young adult children, when you hear that coming out of the mouth of your 21-year-old — “He should know. [laughs] He should just know” — and you just …

哦,好吧。现在我的孩子们都已成年,当你听到从21岁的孩子嘴里说出 "他应该知道 "这句话时,你会...[笑] 他就应该知道" - 你就...

What I also know is that grasping this, what you’re talking about, it’s work. It is the work of life, right? It is the work of growing up.

我还知道,把握这一点,也就是你所说的,是一项工作。这是生活的工作,对吗?这是成长的工作。

de Botton:

德波顿 It’s the work of love. But it’s interesting that you mention your children and children generally, because I think — it sounds eerie, but I think that one of the kindest things that we can do with our lover is to see them as children — and not to infantilize them, but when we’re dealing with children as parents, as adults, we’re incredibly generous in the way we interpret their behavior.

这就是爱的工作。但有趣的是,你提到了你的孩子和一般的孩子,因为我认为--这听起来很阴森,但我认为,我们能对爱人做的最仁慈的事情之一,就是把他们看作孩子--而不是把他们幼稚化,但当我们作为父母、作为成年人与孩子打交道时,我们在解释他们的行为时会非常慷慨。

If a child says — if you walk home, and a child says, “I hate you,” you immediately go, OK, that’s not quite true. Probably they’re tired, they’re hungry, something’s gone wrong, their tooth hurts, something — we’re looking around for a benevolent interpretation that can just shave off some of the more depressing, dispiriting aspects of their behavior. And we do this naturally with children, and yet we do it so seldom with adults. When an adult meets an adult, and they say, “I’ve not had a good day. Leave me alone,” rather than saying, “OK. I’m just going to go behind the facade of this slightly depressing comment…”

如果一个孩子说--如果你走在回家的路上,一个孩子说 "我恨你",你会马上想,好吧,这不完全是真的。也许他们累了,饿了,出了什么事,牙疼了,什么的--我们会四处寻找一种善意的解释,以消除他们行为中一些更令人沮丧和沮丧的方面。我们对孩子自然会这样做,但对成年人却很少这样做。当一个成年人遇到另一个成年人时,他们会说:"我今天过得不好。让我一个人静一静",而不是说 "好吧,我就从这个略微令人沮丧的评论的表象背后......"

Tippett:

蒂皮特 And understand that that’s actually not about me; that’s about what’s going on inside them today.

而且要明白,这其实与我无关,而是与他们今天的内心世界有关。

de Botton:

德波顿 Right, exactly. We don’t do that. We take it all completely personally. And so I think the work of love is to try, when we can manage it — we can’t always — to go behind the front of this rather depressing, challenging behavior and try and ask where it might’ve come from.

没错我们不这么做我们将这一切完全视为个人行为。因此,我认为爱的工作就是,当我们能够做到的时候--我们并不总是能够做到--尝试着去面对这种令人沮丧的、具有挑战性的行为,并尝试着问一问它的来源。

Love is doing that work to ask oneself, “Where’s this rather aggressive, pained, noncommunicative, unpleasant behavior come from?” If we can do that, we’re on the road to knowing a little bit about what love really is, I think.

爱就是扪心自问:"这种咄咄逼人、痛苦、不与人沟通、令人不快的行为从何而来?"如果我们能做到这一点,我想,我们就会对爱的真谛有所了解。

[music: “The Sick System” by Lambert]

[音乐: 兰伯特的 "病态系统"]

Tippett:

蒂皮特I’m Krista Tippett, and this is On Being. Today, a conversation about love with writer and philosopher Alain de Botton.

我是克里斯塔-蒂佩特,这里是《论存在》。今天,我们将与作家兼哲学家阿兰-德波顿进行一场关于爱的对话。

[music: “The Sick System” by Lambert]

[音乐: 兰伯特的 "病态系统"]

Tippett:

蒂皮特I’d love to talk about your — you used this word “pessimism,” a little while ago, and I’d love to dig into that a little bit more. And what you’re really talking about is being reality-based as opposed to being ideal-based. There’s a beautiful video that I’ve shared that’s out there; I think it’s “The Darkest Truth About Love.” Is that right? That’s the title, isn’t it?

我很想谈谈你的--你刚才用了 "悲观主义 "这个词,我很想再深入探讨一下。你真正在说的是基于现实,而不是基于理想。我曾分享过一个很美的视频,我想那就是 "爱的最黑暗真相"。是这样吗?是这个标题吧?

de Botton:

德波顿 Yes, that’s right. Exactly. Made that for YouTube.

是的,没错。没错这是为YouTube做的

Tippett:

蒂皮特 From The School of Life. I’d like to talk through some of these core truths that fly in the face of this way we go around behaving and that movies have taught us to behave and that possibly our parents taught us to behave — these core truths that can put us on the foundation of reality.

来自《生命学校》。我想谈谈其中的一些核心真理,这些真理与我们的行为方式背道而驰,是电影教给我们的行为方式,也可能是我们的父母教给我们的行为方式--这些核心真理能让我们站在现实的基础上。

de Botton:

德波顿 Yes, that’s very useful. We could chisel them in granite. Look, one of the first important truths is, you’re crazy. Not you; as it were, all of us; that all of us are deeply damaged people. The great enemy of love, good relationships, good friendships, is self-righteousness. If we start by accepting that of course we’re only just holding it together and, in many ways, really quite challenging people — I think if somebody thinks that they’re easy to live with, they’re by definition going to be pretty hard and don’t have much of an understanding of themselves. I think there’s a certain wisdom that begins by knowing that, of course, you, like everyone else, is pretty difficult. And this knowledge is very shielded from us. Our parents don’t tell us, our ex-lovers — they knew it, but they couldn’t be bothered to tell us. They sacked us without …

是的,这很有用。我们可以把它们凿在花岗岩上听着,最重要的事实之一就是,你疯了。不是你,而是我们所有人;我们所有人都是深受伤害的人。爱、良好的人际关系、良好的友谊的最大敌人就是自以为是。如果我们一开始就接受这样的事实:当然,我们只是在一起生活而已,而且在很多方面,我们真的是非常具有挑战性的人--我认为,如果有人认为自己很容易相处,那么顾名思义,他们一定会很难相处,而且对自己没有太多的了解。我认为有一种智慧,首先要知道,当然,你和其他人一样,都很难相处。而这些知识对我们来说是非常隐蔽的。我们的父母不告诉我们,我们的前情人--他们知道,但他们懒得告诉我们。他们解雇了我们,却没有...

Tippett:

蒂皮特 Well, by the time they tell us, we’re dismissing what they say anyway. [laughs]

等他们告诉我们的时候,我们已经把他们说的话置之不理了。[笑]

de Botton:

德波顿 Well, that’s right. And our friends don’t tell us, because they just want a pleasant evening with us. So we’re left with a bubble of ignorance about our own natures. And often, you can be way into your 40s before you’re starting to get a sense of, “Well, maybe some of the problem is in me.” Because, of course, it’s so intuitive to think that of course it’s the other person. So to begin with that sense of, “I’m quite tricky; and in these ways” — that’s a very important starting point for being good at love.

嗯,没错。我们的朋友不会告诉我们 因为他们只想和我们度过一个愉快的夜晚所以我们对自己的本性一无所知通常在你40多岁的时候 你才会开始意识到 "也许有些问题出在我身上"当然,直觉告诉我们,问题当然出在别人身上。所以,从 "我很棘手,而且在这些方面 "这种感觉开始--这是善于恋爱的一个非常重要的起点。

So often, we blame our lovers; we don’t blame our view of love. And so we keep sacking our lovers and blowing up relationships, in pursuit of this idea of love which actually has no basis in reality. It’s simply not rooted in anything we know.

我们常常责怪我们的恋人,却不责怪我们的爱情观。于是,我们不断地解雇爱人,破坏人际关系,以追求这种实际上毫无现实基础的爱情观。它根本没有根植于我们所知道的任何事物。

Tippett:

蒂皮特 This right person, this creature, does not exist.

这个正确的人,这个生物,并不存在。

de Botton:

德波顿 And is in fact the enemy of good-enough relationships. I’m really fond of Donald Winnicott, this English psychoanalyst’s term, which he first used in relation to parenting, that what we should be aiming for is not perfection but a good-enough situation. And it’s wonderfully downbeat. No one would go, “What are your hopes this year?” “Well, I just want to have a good-enough relationship.” People would go, “Oh, I’m sorry your life is so grim.” But you want to go, “No, that’s really good. For a human, that’s brilliant.” And that’s, I think, the attitude we should have.

事实上,这也是 "足够好的关系 "的敌人。我很喜欢唐纳德-温尼科特(Donald Winnicott)这个英国精神分析学家的说法,他最早是用在育儿方面的,我们应该追求的不是完美,而是足够好的状态。这是一个很好的顺境。没人会问 "你今年有什么希望?""嗯,我只想有一个足够好的关系"人们会说,"哦,很遗憾你的生活如此灰暗"但你想说,"不,那真的很好对于一个人来说,这真是太棒了。"我想,这才是我们应该有的态度。

Tippett:

蒂皮特 In this “Darkest Truth About Love,” you say the idea of love in fact distracts us from existential loneliness. You are irredeemably alone. You will not be understood. But also, behind that is the — as you say, these are dark truths, but it’s also a relief, as truth always ultimately is, if we can hear it. Again, that is the work of life, is to reckon with what goes on inside us.

在这篇 "关于爱的最黑暗的真相 "中,你说爱的概念实际上分散了我们对存在的孤独的注意力。你是无可救药的孤独。你不会被理解。但同时,在这背后是--如你所说,这些都是黑暗的真相,但也是一种解脱,因为真相最终总是如此,如果我们能听到它。同样,这也是生命的工作,是对我们内心世界的反思。

de Botton:

德波顿 I think one of the greatest sorrows we sometimes have in love is the feeling that our lover doesn’t understand parts of us. And a certain kind of bravery, a certain heroic acceptance of loneliness seems to be one of the key ingredients to being able to form a good relationship.

我认为,我们有时在爱情中最大的悲哀之一,就是觉得爱人不理解我们的某些部分。而某种勇敢,某种对孤独的英雄式接受,似乎是能够建立良好关系的关键因素之一。

Tippett:

蒂皮特 Isn’t that interesting? And it sounds paradoxical.

这难道不有趣吗?而且听起来很矛盾。

de Botton:

德波顿 Of course. If you expect that your lover must understand everything about you, you will be — well, you’ll be furious pretty much all the time. There are islands and moments of beautiful connection, but we have to be modest about how often they’re going to happen. I think if you’re lonely with only — I don’t know — 40 percent of your life, that’s really good going. You may not want to be lonely with over 50 percent, but I think there’s certainly a sizable minority share of your life which you’re going to have to endure without echo from those you love.

当然。如果你期望你的爱人必须了解你的一切,那么你就会--嗯,你会一直都很生气。有一些岛屿和美好的联系时刻,但我们必须谦虚地对待它们发生的频率。我认为,如果你一生中只有 40% 的时间是孤独的,那就很不错了。你可能不希望有超过 50% 的时间是孤独的,但我认为,在你的生命中,肯定有相当一部分时间,你必须忍受没有来自你所爱的人的呼应。

Tippett:

蒂皮特 You know, I debated over whether I would discuss this with you, but I think I will. I’m single right now and have been for a few years, and it’s actually been a great joy. Not that I think I will be single forever or want to be single forever, although actually I think I would be all right if I were, which is a real watershed. And also, what this chapter of life has taught me to really enjoy more deeply and take more seriously are all the many forms of love in life aside from just romantic love or being coupled. Do people talk to you about that?

你知道,我一直在犹豫是否要和你讨论这个问题,但我想我会的。我现在是单身,而且已经单身了好几年,这其实是一件非常快乐的事情。这并不是说我会永远单身,也不是说我想永远单身,虽然实际上我觉得如果我单身的话,我也会过得很好,这是一个真正的分水岭。此外,人生的这一篇章让我学会了更深入地享受和更认真地对待生活中的各种形式的爱,而不仅仅是浪漫的爱情或夫妻生活。人们会和你谈论这些吗?

de Botton:

德波顿 Well, it’s funny, because just as you were saying, “I’m single,” I was about to say, “You’re not.” Because we have to look at what this idea of singlehood is. We’ve got this word, “single,” which captures somebody who’s not got a long-term relationship.

说来好笑,就在你说 "我是单身 "的时候 我正想说 "你不是"因为我们得看看 "单身 "是个什么概念我们有一个词,"单身",用来形容没有长期关系的人。

Tippett:

蒂皮特 But I have so much love in my life.

但我的生活中充满了爱。

de Botton:

德波顿 That’s right. And another way of looking at love is connection. We’re all the time, we are hardwired to seek connections with others. And that is in a sense, at a kind of granular level, what love is. Love is connection. And insofar as one is alive and one is in buoyant, relatively buoyant spirit some of the time, it’s because we are connected. And we can take pride in how flexible our minds ultimately are about where that connection is coming.

这就对了。另一种看待爱的方式是联系。我们无时无刻不在寻求与他人的联系从某种意义上说,在某种细微的层面上,这就是爱。爱就是联系。只要一个人还活着,只要一个人在某些时候还能精神饱满,相对精神饱满,那是因为我们彼此相连。我们可以引以为豪的是,我们的思维最终是多么灵活,我们知道这种联系来自何方。

And I think it’s also worth saying that, for some people, relationships are not necessarily the place where they encounter their best selves; that, actually, the person that they are in a relationship is not the person that they want to be or that they can be in other areas of life; that they feel that there are other possibilities that they’d like to explore. And I think getting into a relationship with someone, asking someone to be with you is a pretty cruel thing to do to someone that you love and admire and respect, because the job is so hard. Most people fail at it.

我认为还值得一说的是,对有些人来说,恋爱关系并不一定是他们遇见最好的自己的地方;实际上,他们在恋爱关系中的样子并不是他们想要成为的样子,也不是他们在生活的其他方面可以成为的样子;他们觉得还有其他的可能性,他们想要去探索。我认为,与一个人谈恋爱,要求一个人和你在一起,对一个你所爱、钦佩和尊重的人来说,是一件非常残忍的事情,因为这份工作太难了。大多数人都会失败

When you ask someone to marry you, for example, you’re asking someone to be your chauffeur, co-host, sexual partner, co-parent, fellow accountant, mop the kitchen floor together, etc., etc., and on and on the list goes. No wonder that we fail at some of the tasks and get irate with one another. It’s a burden. And I think sometimes, the older I get, sometimes I think one of the nicest things you can do to someone that you really admire is leave them alone. Just let them go. Let them be. Don’t impose yourself on them, because you’re challenging.

例如,当你向某人求婚时,你就在要求对方成为你的司机、共同主持人、性伴侣、共同父母、同僚会计师、一起拖厨房地板,等等等等,不一而足。难怪我们会在某些任务上失败,并对彼此恼怒。这是一种负担。我想,有时候,随着年龄的增长,我觉得你能做的对你真正敬佩的人最好的事情之一就是别管他们。让他们去吧随他们去吧不要把自己强加给他们 因为你很有挑战性

Tippett:

蒂皮特 I want to read this definition of marriage that you’ve written in a few places — I think it’s wonderful — and just talk about this. “Marriage ends up as a hopeful, generous, infinitely kind gamble taken by two people who don’t know yet who they are or who the other might be, binding themselves to a future they cannot conceive of and have carefully avoided investigating.”

我想读一读你在一些地方写的关于婚姻的定义--我觉得它很好--然后谈谈这个。"婚姻最终是一场充满希望的、慷慨的、无限善良的赌博 两个还不知道自己是谁,也不知道对方可能是谁的人

de Botton:

德波顿 Well, yes. [laughs] It’s challenging. And it’s certainly contrary to the romantic view. But again, this kind of realism or acceptance of complexity, I think, is ultimately the friend of love. I’m not — look, it’s also worth adding — I don’t believe that everybody should stay in exactly the relationship that they’re in, and that any relationship is worth sticking with, and that, in a way, the fault is always the fault of the lovers, if it’s not — both lovers, if it’s not happy. There are legitimate reasons to leave a relationship.

是的[很有挑战性当然也有悖于浪漫主义的观点但同样的,我认为这种现实主义或对复杂性的接受 归根结底是爱情之友我并不是--听着,还有一点值得补充--我并不认为每个人都应该保持他们现在所处的关系,任何关系都值得坚持,而且,从某种程度上来说,如果这段关系不幸福--恋人双方都不幸福,错总是恋人双方的错。离开一段感情是有正当理由的。

But when you’re really being honest, if you ask yourself, “Why am I in pain?” and you can’t necessarily attribute all the sorrows that you’re feeling to your lover, if you recognize that some of those things are perhaps endemic to existence or endemic to all human beings or something within yourself, then what you’re doing is encountering the pain of life with another person, but not necessarily because of another person.

但当你真正坦诚时,如果你问自己:"我为什么痛苦?"你不一定能把所有的悲伤都归咎于你的爱人,如果你认识到其中有些事情也许是存在的特有现象,或者是全人类的特有现象,或者是你自己内心的某些东西,那么你所做的就是与另一个人一起遭遇人生的痛苦,但不一定是因为另一个人。

Tippett:

蒂皮特 And, for example, you are in fact arguing — as you said before, some marriages are meant to end. And there’s certainly reasons for marriages to end or to end marriages. But you also point out this very contradictory fact that the thing that’s ultimately wrong with adultery as an easy out to what’s going wrong in the marriage is that it is based on the same idealism that certain ideas of marriages are based on that go wrong.

比如说,你实际上是在争辩--正如你之前所说,有些婚姻是注定要结束的。婚姻结束或结束婚姻肯定是有原因的。但你也指出了一个非常矛盾的事实,那就是通奸作为解决婚姻问题的一个简单办法,其最终的错误在于它是建立在理想主义的基础上的,而某些婚姻观念也是建立在理想主义的基础上的。

de Botton:

德波顿 That’s right, in a way that you’re just redirecting your hope elsewhere.

没错,在某种程度上,你只是把希望转移到了别处。

Tippett:

蒂皮特Imagining this is the perfect one, right? This is the one person with whom you won’t ever be lonely again; who will understand you completely.

想象一下,这是一个完美的人,对吗?和他在一起,你再也不会感到孤独;他会完全理解你。

de Botton:

德波顿 That’s right. And so it’s — on and on the cycles of hurt continue.

这就对了。就这样,伤害循环往复。

Tippett:

蒂皮特 Something else you name about marriage that I feel is not often enough just named is that — we spoke a little while ago about children coming into a marriage. And of course, children teach us so much. One thing you say that’s beautiful, that “children teach us that love in its purest form is a kind of service”; that the love we have for our children — I certainly know this with myself — that the love I have for my children has changed me, and it is distinct from all the other loves I’ve ever known.

你提到的关于婚姻的其他一些事情,我觉得还不够经常被提及,那就是--我们刚才谈到了孩子进入婚姻的问题。当然,孩子教会了我们很多。有一件事你说得很好,"孩子教会我们,最纯粹的爱是一种服务";我们对孩子的爱--我自己当然深有体会--我对孩子的爱改变了我,它不同于我所知道的其他所有的爱。

But also that children are hard on marriages, right? And I think, on a more complicated level, if there are problems in a marriage, that can get amplified when children are there. And it’s also partly because you just get — everybody’s tired. Right? [laughs]

但孩子对婚姻也很不利,对吗?我认为,从更复杂的层面来看,如果婚姻中存在问题,有了孩子之后,问题就会被放大。部分原因还在于,每个人都会感到疲惫。对不对?[笑]

de Botton:

德波顿 That’s right. It’s interesting; in a way, there’s a lot of mundanity in relationships. And one of the things that romanticism does is to teach us that the great love stories should be above the mundane. So in none of the great, say, 19th-century novels about love does anyone ever do the laundry, does anyone ever pick up the crumbs from the kitchen table, does anyone ever clean the bathroom. It just doesn’t happen, because it’s assumed that what makes or breaks love are just feelings, passionate emotions, not the kind of day-to-day wear and tear.

这就对了。有趣的是,在某种程度上,人际关系中有很多世俗的东西。而浪漫主义所做的一件事 就是告诉我们 伟大的爱情故事应该超越世俗因此,在19世纪伟大的爱情小说中,没有人洗衣服,没有人收拾餐桌上的碎屑,没有人打扫浴室。这一切都不会发生,因为人们假定,爱情的成败只是感觉,是激情澎湃的情感,而不是日复一日的磨损。

And yet, of course, when we find ourselves in relationships, it is precisely over these areas that conflicts arise, but we refuse to lend them the necessary prestige. There’s no arguments as vicious as when two people are arguing about something, but both of them think the argument is trivial. So they’ll say things like, “Oh, it’s absurd, we’re arguing over who should hang up the towels in the bathroom. That’s for stupid people.”

当然,当我们发现自己处于人际关系中时,恰恰是在这些方面产生了冲突,但我们却拒绝赋予它们必要的威信。最恶毒的争吵莫过于两个人在争论某件事情,但都认为争论无关紧要。所以他们会说 "哦,这太荒谬了,我们在争论谁应该把毛巾挂在浴室里。那是愚蠢的人才会做的事"

Tippett:

蒂皮特 [laughs] Right — “That has nothing to do with …”

[笑] 对 - "这与......"

de Botton:

德波顿 And you know that that’s going to be trouble. And so we need, in a way — one of the lessons of love is to lend a bit of prestige to those issues that crop up in love, like who does the laundry and on what day. We rush over these decisions. We don’t see them as legitimate. We think it’s fine to …

你知道这会带来麻烦。因此,从某种程度上说,我们需要--爱情的课程之一,就是给爱情中出现的问题一点威信,比如谁洗衣服,哪天洗。我们急于做出这些决定。我们不认为它们是合法的。我们认为...

Tippett:

蒂皮特 But they are.

但它们确实是。

de Botton:

德波顿 But they are. As you say, there’s a lot of life that is extremely mundane.

但它们确实是。正如你所说,生活中有很多事情是极其平凡的。

Tippett:

蒂皮特It is the stuff of life. Right. It’s the stuff of our days. There’s this wonderful line from The Course of Love about these two parents with children: “The tired child inside each of them is furious at how long it has been neglected and in pieces.”

这就是生活。对它是我们生活的全部。《爱的历程》里有句话说得很好 关于这对有孩子的父母"他们每个人内心深处疲惫的孩子 都在为自己长期被忽视和支离破碎而愤怒"

de Botton:

德波顿 That’s right. And in a way — it’s so funny. If I can be indiscreet on air, my wife used to say to me, in the early days of our marriage, she sometimes would say to me things like, “My father would never have said something like” — and I would say something, “It’s not my turn to make the tea” or something. She’ll go, “My father would never have said it. He would always do this for us.”

这就对了。从某种意义上说,这太有趣了。如果我可以在节目中放肆一下的话,我妻子过去常对我说,在我们结婚初期,她有时会对我说,"我父亲绝不会说这样的话"--我会说 "轮不到我泡茶 "之类的话。她就会说,"我父亲永远不会这么说。他总是为我们做这些

And then I had to point out that there was really a — she wasn’t comparing like with like. She was comparing this man, her father, as a father, but not as a lover. And in the end, what I say to her, did end up saying to her was, “In a way, I’m probably behaving exactly like your father, but just not the father that you saw when he was around you.”

然后我不得不指出,她并没有把同类与同类进行比较。她在比较这个男人,她的父亲,作为一个父亲,但不是作为一个情人。最后,我对她说,最后我对她说 "在某种程度上,我的行为可能和你父亲一模一样" "只是和你父亲在你身边时的样子不一样"

Tippett:

蒂皮特 The way he behaved towards your mother. [laughs]

他对你母亲的态度[笑声]

de Botton:

德波顿 [laughs] That’s right. Exactly. And so one of the things we do as parents is to edit ourselves, which is lovely in a way, for our children. But it gives our children a really unnatural sense of what you can expect from another human being, because we’re never as nice to probably anyone else on Earth as we are to our children. I’m saying this is the cost of good parenting.

没错没错所以作为父母,我们要做的一件事 就是编辑我们自己 这在某种程度上对我们的孩子来说很可爱但这会给孩子一种不自然的感觉 你能从另一个人身上得到什么 因为我们对地球上的任何人都不如对我们的孩子好我是说,这就是好父母的代价。

[music: “Red Virgin Soil” by Agnes Obel]

[音乐: 阿格尼丝-奥贝尔的《红色处女地》]

Tippett:

蒂皮特 After a short break, more with Alain de Botton. You can always listen again, and hear the unedited version of this and every conversation I have on the On Being podcast feed, wherever podcasts are found.

稍事休息后,我们将继续与阿兰-德波顿进行对话。您可以随时在 "存在 "播客频道(On Being podcast feed)上再次收听或收听未经编辑的本期对话以及我的每一次对话,无论在哪里都能找到播客。

[music: “Red Virgin Soil” by Agnes Obel]

[音乐: 阿格尼丝-奥贝尔的《红色处女地》]

I’m Krista Tippett, and this is On Being. Today, we are exploring the true hard work of love with the writer and philosopher Alain de Botton. This is one of the most popular shows we’ve ever created. And it’s an offering of anchoring truths in a pandemic that has tested the mettle of love in every home and relationship.

我是克里斯塔-蒂佩特,这里是《论存在》。今天,我们将与作家兼哲学家阿兰-德波顿一起探讨爱的真谛。这是我们有史以来最受欢迎的节目之一。这档节目提供了在大流行病中的锚定真理,这些大流行病考验着每个家庭和关系中爱的坚韧度。

Tippett:

蒂皮特I’d like to go a slightly different place with all of this. The things you’ve been saying, pointing out about how love really works — that people don’t learn when they’re humiliated; that self-righteousness is an enemy of love — I’m thinking a lot right now, these days, about how and if we could apply the intelligence we actually have with the experience of love — not the ideal, but the experience of love in our lives — to how we can be, as citizens, moving forward. There’s a lot of behavior in public — I’m just speaking for the United States, but I think there are forms of this in the UK, as well — we’re kind of acting out in public the way we act out at our worst in relationships. [laughs]

我想从一个稍微不同的角度来谈谈这一切。你一直在说的那些话,指出了爱是如何真正起作用的--人们在受到羞辱时不会学习;自以为是是爱的敌人--我现在想了很多,这些天,我在想,如果我们能把我们实际拥有的爱的经验--不是理想,而是我们生活中爱的经验--的智慧,应用到我们作为公民如何向前迈进。在公共场合有很多行为--我只是针对美国而言,但我认为在英国也有这样的形式--我们在公共场合的表现就像我们在人际关系中最糟糕时的表现一样。[笑]

de Botton:

德波顿 I think that’s fascinating; I think you’re onto something huge and rather counterintuitive, because we associate the word “love” with private life. We don’t associate it with life in the republic; with civil society. But I think that a functioning society requires — well, it requires two things that, again, just don’t sound very normal, but they require love and politeness. And by “love” I mean a capacity to enter imaginatively into the minds of people with whom you don’t immediately agree, and to look for the more charitable explanations for behavior which doesn’t appeal to you and which could seem plain wrong; not just to chuck them immediately in prison or to hold them up in front of a law court, but to —

我认为这很吸引人;我认为你发现了一些巨大的、相当反直觉的东西,因为我们把 "爱 "这个词与私人生活联系在一起。我们不会把它与共和国的生活联系起来,与公民社会联系起来。但我认为,一个正常运转的社会需要--嗯,需要两样东西,同样,听起来不太正常,但它们需要爱和礼貌。我所说的 "爱",是指一种能力,即以想象力进入那些你并不立即同意的人的内心,并为那些你不喜欢的、看起来可能是完全错误的行为寻找更仁慈的解释;而不仅仅是把他们立即关进监狱,或在法庭上把他们关起来,而是

Tippett:

蒂皮特 Or just tell them how stupid they are, right?

或者直接告诉他们他们有多愚蠢,对吗?

de Botton:

德波顿 Right. Exactly. We’re permanently — all sides are attempting to show how stupid every other side is. And the other thing, of course, is politeness, which is an attempt not necessarily to say everything: to understand that there is a role for private feelings, which, if they were to emerge, would do damage to everyone concerned.

没错。没错我们一直都在--各方都在试图展示另一方有多愚蠢。当然,还有一点就是礼貌,这也是一种尝试,不一定要把什么都说出来:要明白私人情感也有其作用,如果私人情感出现,会对每个相关的人造成伤害。

But we’ve got this culture of self-disclosure. And as I say, it spills out into politics as well. The same dynamic goes on of, like, “If I’m not telling you exactly what I think, then I may develop a twitch or an illness from not expunging my feelings.” To which I would say, “No, you’re not. You’re preserving the peace and good nature of the republic, and it’s absolutely what you should be doing.”

但我们已经有了这种自我披露的文化。正如我所说,这种文化也蔓延到了政治领域。同样的动力也在继续,比如,"如果我不告诉你我的真实想法,那么我可能会因为不表达我的感受而患上抽搐或疾病"。对此,我会说:"不,你没有。你是在维护共和国的和平与善良 这绝对是你应该做的"

Tippett:

蒂皮特 Yes. And I guess — I’ve been having this conversation with a lot of people this year — the truth is, more than ever before perhaps in our world, we are in relationship. We are connected to everyone else. And that’s a fact. Their well-being will impact our well-being; is of relevance to our well-being, and that of our children.

是的。我想--今年我和很多人都有过这样的对话--事实是,也许在我们的世界里,我们比以往任何时候都更有关系。我们与其他人息息相关。这是事实。他们的幸福会影响我们的幸福;与我们和我们孩子的幸福息息相关。

But we have this habit and this capacity in public — and also we know that our brains work this way — to see the other — to see those strangers, those people, those people on the other side politically, socioeconomically, whatever, forgetting that in our intimate lives and in our love lives, in our circles of family and friends and in our marriages and with our children, there are things about the people we love the most, who drive us crazy, that we do not comprehend, and yet we find ways to be intelligent, to be loving — because it gets a better result. [laughs]

但是,我们在公共场合有这样的习惯和能力--我们也知道我们的大脑是这样工作的--去看待他人--去看待那些陌生人、那些人、那些在政治、社会经济等方面站在另一方的人,而忘记了在我们的亲密生活中,在我们的爱情生活中,在我们的亲友圈子中,在我们的婚姻中,在我们的孩子身上,我们最爱的人也有一些让我们疯狂的事情,我们无法理解,但我们还是想方设法去表现得聪明、去表现得有爱--因为这样会得到更好的结果。[笑]

de Botton:

德波顿 That’s right. And families are at this kind of test bed of love, because we can’t entirely quit them. And this is what makes families so fascinating, because you’re thrown together with a group of people who you would never pick, if you could simply pick on the grounds of compatibility. Compatibility is an achievement of love. It shouldn’t be the precondition of love, as we nowadays, in a slightly spoiled way, imagine it must be.

这就对了。家庭是爱的试验田 因为我们无法完全放弃家庭这就是家庭的魅力所在,因为你会和一群你永远不会选择的人在一起,如果你可以简单地根据兼容性来选择的话。兼容性是爱情的成就。它不应该是爱情的先决条件,就像我们现在以一种略带溺爱的方式所想象的那样。

Tippett:

蒂皮特Yes. Wonderful. I think this is deeply politically relevant.

是的。好极了我认为这具有深刻的政治意义。

de Botton:

德波顿 Totally. And I think if we just try and explore the word “political,” political really means “outside of private space.” And we’re highly socialized creatures who really take our cues from what is going on around us. And if we see an atmosphere of short tempers, of selfishness, etc., that will bolster those capacities within ourselves. If we see charity being exercised, if we see good humor, if we see forgiveness on display: again, it will lend support to those sides of ourselves. And we need to take care what we’re exposing ourselves to, because too much exposure to the opposite of love makes us into very hostile and angry people.

完全正确我认为,如果我们试着探究一下 "政治 "这个词 政治的真正含义是 "私人空间之外"我们是高度社会化的生物 会从周围发生的事情中得到启示如果我们看到一种脾气暴躁、自私自利的氛围,就会增强我们自身的能力。如果我们看到有人乐善好施,如果我们看到有人幽默风趣,如果我们看到有人宽容大度:同样,这也会支持我们自身的这些方面。我们需要注意我们所接触的事物,因为过多地接触与爱相反的事物会让我们变得非常敌对和愤怒。

Tippett:

蒂皮特 Yes, and I think it’s also such an important thing to bear in mind, that the import of our conduct, moment to moment — that that is having effects that we can’t see.

是的,我认为这也是一件非常重要的事情,我们要牢记,我们每时每刻的行为都在产生着我们无法看到的影响。

de Botton:

德波顿 That’s right. We’re far more sensitive than we allow for. And we need to build a world that recognizes that if somebody goes “mm-hmm” rather than this, or “thanks” rather than “yes,” or whatever it is, this can ruin our day. And we should think about that as we approach not just our personal relationships, but also our social and political relationships. These things are humiliating. Little things can deeply wound and humiliate.

没错。我们比自己想象的要敏感得多。我们需要建立一个这样的世界,认识到如果有人说的是 "嗯哼 "而不是这个,或者 "谢谢 "而不是 "是的",或者不管是什么,这都会毁了我们的一天。我们在处理个人关系、社会关系和政治关系时,都应该考虑到这一点。这些事情是令人羞辱的。小小的事情就能深深地伤害和羞辱人。

Let’s not forget that one of the things that makes relationships so scary is, we need to be weak in front of other people. And most of us are just experts at being pretty strong. We’ve been doing it for years. We know how to be strong. What we don’t know how to do is to make ourselves safely vulnerable, and so we tend to get very twitchy, preternaturally aggressive, etc., when we’re asked to — when the moment has come to be weak.

我们不要忘记,人际关系之所以如此可怕,其中一个原因就是我们需要在别人面前示弱。而我们中的大多数人都是表现强势的专家。我们已经这样做了很多年。我们知道如何变得强大。我们不知道如何让自己安全地变得脆弱,所以当我们被要求--当我们需要变得脆弱的时候--我们往往会变得非常抽搐、具有超自然的攻击性等等。

Tippett:

蒂皮特 And I feel like there’s almost this calling now, because the stakes are so high, for emotional intelligence in public, which of course, we don’t — none of us gets perfectly in our intimate lives, but we do know these things about people we love. And they’re also true of people we don’t know and don’t think we love.

我觉得现在几乎有这样一种呼唤,因为赌注如此之大,在公众面前需要情商,当然,我们在亲密生活中并没有--我们没有人能够做到完美,但我们确实了解我们所爱的人的这些事情。但我们确实知道我们所爱的人的这些特质,而这些特质也同样适用于我们不了解、不认为我们爱的人。

But I want to return a little bit to love and sex and eros and all of this. I have to say, one thing I really love and appreciate and learned from in your writing is your reflection on flirting [laughs] as an art, the art of flirting; that it can be something edifying, a pleasurable gift. And you have this phrase, a “good flirt.” So would you describe what a “good flirt” is?

但我还是想回到爱、性、情欲和所有这些方面。我不得不说,我非常喜欢、欣赏并从你的写作中学到的一点是,你把调情[笑]视为一门艺术,调情的艺术;它可以是一种熏陶,一种愉悦的礼物。你有这样一句话,"好的调情"。你能描述一下什么是 "调情高手 "吗?

de Botton:

德波顿 Well, if you think about what flirtation is, in many ways flirtation is the attempt to awaken somebody else to their attractiveness. I think it would be such a pity if we had to drive something as important as validation and self-acceptance and a pleasant view of oneself through the gate of — the rather narrow gate of sex.

如果你想一想什么是调情 从很多方面来说 调情就是试图唤醒别人的吸引力我认为,如果我们不得不通过性这扇相当狭窄的大门,来推动像认可、自我接纳和对自己的愉悦看法这样重要的事情,那将是多么遗憾的一件事。

And flirtation is a kind of act of the imagination. And what’s fun about flirtation is that it often happens between really quite unlikely people. Two people meet, and maybe they’re both with someone, or there’s a difference in status or background, etc., and they can find that they’re in a little conversation about the weather, and both parties will recognize, there’s something a little bit flirtatious going on. And it’s got really nothing to do with sex, as such; it’s just two people delighting in awakening one another …

调情是一种想象力的行为。调情的有趣之处在于,它常常发生在不太可能的人之间。两个人相遇,也许他们都和某个人在一起,也许他们的地位或背景有差异,等等,他们会发现他们在谈论天气的时候,双方都会意识到,有一些调情的事情正在发生。这其实与性无关,它只是两个人唤醒彼此的喜悦......

Tippett:

蒂皮特 It’s pleasant. Right.

很惬意对

de Botton:

德波顿 … to the fact that they’re quite nice people, and they’re quite attractive, and that that’s OK.

......事实上,他们是很好的人,他们很有魅力,这就够了。

Tippett:

蒂皮特 You also have this lovely film, it’s one of these School of Life films, about this, a good flirt. You can make these assumptions that this other person maybe would love to sleep with us, won’t sleep with us, and the reason why they won’t has nothing to do with any deficiency on our part. But it’s also not, as you say, a deception. It’s a natural, pleasurable human experience.

你还看过一部很好看的电影,是 "生活学校 "的电影之一,讲的是如何调情。你可以做出这样的假设:这个人可能很想和我们上床,但又不愿意和我们上床,而他们不愿意的原因与我们的缺陷无关。但这也不像你说的那样,是一种欺骗。这是一种自然的、愉悦的人类体验。

de Botton:

德波顿 That’s right. The other thing that we get quite wrong in our culture is the whole business of what sex actually is, because we’ve come from a Freudian world. Freud has told us that there’s a lot more going on in sex than we want to believe and that a lot of it is quite weird, and darker than we’d ever want to imagine, and that sex is everywhere in life, even in places where we don’t think it is or perhaps should be.

没错。在我们的文化中,还有一件事是错误的 那就是性到底是什么 因为我们来自弗洛伊德的世界弗洛伊德告诉我们,性比我们想相信的要复杂得多 很多事情都很奇怪,比我们想想象的要黑暗得多 性在生活中无处不在,甚至在我们认为不存在或不应该存在的地方也是如此

But, in a way, I’ve got a sort of different view of this. I think that it’s not so much that sex is everywhere, it’s that psychological dynamics are everywhere, even in sex. And so often we think of sex as just a sort of pneumatic activity, but really, it’s a psychological activity. And if you try to imagine why people are excited by sex, it’s not so much that it’s a pleasurable nerve-ending business. It’s ultimately that it’s about acceptance.

但在某种程度上,我对此有不同的看法。我认为与其说性无处不在,不如说心理动态无处不在,甚至在性中也是如此。我们常常认为性只是一种气动活动,但实际上,它是一种心理活动。如果你试着想象一下人们为什么会对性感到兴奋,那并不是因为它是一种令人愉悦的神经末梢活动。归根结底,它与接受有关。

If you think about, why is it exciting to kiss someone for the first time? It’s probably more fun eating an oyster or flossing your teeth or watching TV than kissing. It’s a bit weird. What’s this odd thing we call kissing? It’s like sort of trying to inflate somebody else’s mouth. It’s just odd.

如果你仔细想想,第一次亲吻一个人为什么会令人兴奋?吃牡蛎、用牙线剔牙或看电视可能比接吻更有趣。这有点奇怪。我们所说的接吻是怎么回事?就像给别人的嘴充气一样很奇怪

Tippett:

蒂皮特 [laughs]

[笑]

de Botton:

德波顿 Nevertheless, we like it, not because of its physical feeling but because of what it means, the meaning we infuse. And the meaning we infuse into it is, “I accept you. And I accept you in a way that is incredibly intimate and that would be quite revolting with anyone else. I’m allowing you into my private space as a way of signaling, ‘I like you.’” And what really — we call it getting “turned on,” but what we’re really, as it were, excited by is that someone accepts us with remarkable — in all our…

然而,我们喜欢它,不是因为它的物理感觉,而是因为它的含义,我们注入的意义。我们赋予它的含义是:"我接受你。我接受你的方式非常亲密,如果是其他人,一定会非常反感。我允许你进入我的私人空间,以此来表示'我喜欢你'"。而真正的--我们称之为 "兴奋",但我们真正兴奋的是,有人以非凡的方式接受了我们--在我们所有的...

Tippett:

蒂皮特 Takes delight in us.

以我们为乐

de Botton:

德波顿 Right; takes delight in us. And that’s what’s exciting about it. In other words, sex is continuous with a lot of things that we’re interested in outside of the bedroom.

是的,我们很高兴。这才是令人兴奋的地方。换句话说,性爱与很多我们在卧室之外感兴趣的事情是相辅相成的。

Tippett:

蒂皮特 And you say that flirting is one way to experience, in the course of ordinary life, in a way that’s completely nonthreatening to whatever your commitments are, what is enjoyable about sex that’s not necessarily the act itself: the fact that we are sexual beings.

你说,调情是在普通生活中体验的一种方式,无论你的承诺是什么,调情都是一种完全不具威胁性的方式,是性爱中令人愉悦的东西,而不一定是性行为本身:我们是性的存在这一事实。

de Botton:

德波顿 That’s right. That’s right. But we feel often conflicted about it. “I shouldn’t be flirting. I can’t flirt,” etc. So there’s a lot of fear of — there’s a lot of fear of slippery slopes. In many situations, we can hang on, on the slippery slope. It’s OK. We’ve got tools to hang on in there.

这就对了没错但我们常常为此感到矛盾"我不应该调情。我不能调情 "等等。因此,我们会有很多恐惧--对滑坡的恐惧。在很多情况下,我们可以在滑坡上坚持下去。没事的。我们有工具在那里坚持下去。

Tippett:

蒂皮特 I want to know — I don’t want to let you go before asking what you think about — what’s your view of online dating? Because this a new way that so many people, perhaps most people, moving forward, are meeting, are engaging this romantic side of themselves.

我想知道--在问你对网上约会的看法之前,我不想让你离开--你对网上约会有什么看法?因为这是一种新的方式,许多人,也许是大多数人,都在通过这种方式来认识、接触自己浪漫的一面。

de Botton:

德波顿 Look, at one level, online dating promises to open up something absolutely wonderful, which is a more logical way of getting together with someone. The sort of dream is that the secrets of our soul and the secrets of somebody else’s soul will be sort of downloaded onto a computer and that we will find the best possible match for who we are.

听着,从某种程度上来说,网上交友承诺会带来一些绝对美妙的东西,这是一种更合乎逻辑的与人相处的方式。我们的梦想是,我们灵魂的秘密和别人灵魂的秘密将被下载到电脑上,我们将找到最适合我们的人。

The darker side of online dating is that it encourages the idea that a good relationship must mean a conflict-free relationship. And therefore, any relationship which has conflict in it, which has unhappiness and areas of tension in it, is wrong and can be terminated, because we have this wonderful backup, which is alternatives. So, like any tool, it’s got its pluses and minuses and has to be used correctly. And I think what I mean by “correctly” is, it has to broaden the pool of people from which we’re choosing our lovers, while not giving us the illusion that there is such a thing as a perfect human being.

网恋的阴暗面在于,它助长了一种观念,即良好的关系一定意味着没有冲突的关系。因此,任何有冲突、不快乐和紧张的关系都是错误的,都是可以终止的,因为我们有这种奇妙的备份,那就是替代品。因此,就像任何工具一样,它有优点也有缺点,必须正确使用。我想我所说的 "正确 "是指,它必须扩大我们选择爱人的范围,同时不会让我们产生错觉,以为世上存在完美的人。

Tippett:

蒂皮特 Right. So then you’re back to the basic truth, [laughs] the darker truth about love. Also, what online dating does is it introduces you to people, but then, really, the whole thrust of your thinking is that loving is really what comes next. That’s what comes after the meeting.

没错所以,你又回到了基本的真相,[笑] 关于爱情的黑暗真相。另外,网恋的作用是把你介绍给别人,但实际上,你的整个想法是,爱才是真正的下一步。那是见面之后的事情。

de Botton:

德波顿 That’s right. Silicon Valley has been incredibly interested in getting us to that first stage of meeting the person, and that’s great. But the next stage has been abandoned. Where is the app that will tell you how to read, how to interpret somebody else’s confused signals of distress or that will remind you, at a certain point, to look charitably upon someone’s behavior because you remember their childhood, etc.? So we have a long way to go.

没错。硅谷对让我们完成与人见面的第一阶段非常感兴趣,这很好。但下一阶段却被抛弃了。哪里有一款应用程序能告诉你如何解读别人困惑的求救信号,或者在某一时刻提醒你,因为你还记得某人的童年,所以要善待他的行为,等等?因此,我们还有很长的路要走。

Our technology is still — look, we’re still — it sounds odd, because it’s one of the sort of narcissisms of our time that we think we’re living late on in the history of the world. We think we’re sort of — we’re latecomers to the party. We’re still at the very beginning of understanding ourselves as human, emotional creatures. We’re still taking our first baby steps in the understanding of love, and we need a lot of compassion for ourselves. And no wonder we make horrific mistakes pretty much all the time.

我们的技术仍然--听着,我们仍然--这听起来很奇怪,因为这是我们这个时代的一种自恋,我们认为我们生活在世界历史的晚期。我们认为我们是--我们是派对的迟到者。我们还处在将自己理解为人类、情感动物的起步阶段。我们对爱的理解还在起步阶段,我们需要对自己充满同情。难怪我们总是会犯下可怕的错误。

[music: “Turquoise” by Mooncake]

[音乐: 月饼的 "绿松石"]

Tippett:

蒂皮特I’m Krista Tippett, and this is On Being. Today, a conversation about love with writer and philosopher Alain de Botton.

我是克里斯塔-蒂佩特,这里是《论存在》。今天,我们将与作家兼哲学家阿兰-德波顿进行一场关于爱的对话。

[music: “Turquoise” by Mooncake]

[音乐: 月饼的 "绿松石"]

Tippett:

蒂皮特I happened to see your tweet at the end of 2016, when The New York Times released its most-read articles of the year, [laughs] and your “Why You’ll Marry the Wrong Person” was No. 1, which is really extraordinary; the most-read article in a year of the Brexit vote, the presidential election, war, refugee crisis. I wonder what that tells you about us as a species.

2016年年底,《纽约时报》发布了年度阅读量最高的文章,我碰巧看到了你的推文,[笑]你的文章《为什么你会嫁错人》排名第一,这真的很不寻常;在英国脱欧投票、总统大选、战争、难民危机的一年里,这篇文章的阅读量最高。我想知道这对我们人类有何启示。

de Botton:

德波顿 Look, it was deeply fascinating and quite extraordinary. And apparently, it was first by a long way. It’s just peculiar. And I think that — look, first of all, it tells us that we have an enormous loneliness around our difficulties. One could write a follow-on piece — I may or may not — called, “Why You Will Get Into the Wrong Job,” which would probably score quite highly too, and “Why You’ll Have the Wrong Child” and “Why You’ll Go on the Wrong Vacation” and “Why Your Body Will Be the Wrong Shape” and “Why You’ll Think You Live in the Wrong Country,” etc. And in a way, we need solace for the sense that we have gone wrong in an area, whatever it may be, where perfection was possible.

听着,它深深地吸引着我,而且非同寻常。而且很显然,这是第一次。这太奇特了。我认为--你看,首先,它告诉我们,我们在困难面前有一种巨大的孤独感。我们可以写一篇后续文章--我可能写,也可能不写--叫做 "为什么你会找错工作",这篇文章的得分可能也会很高,还有 "为什么你会生错孩子","为什么你会去错误的地方度假","为什么你的身体会是错误的形状","为什么你会认为你生活在错误的国家",等等。在某种程度上,我们需要慰藉,因为我们觉得自己在某个领域出了错,不管是什么领域,而在这个领域,完美是有可能实现的。

And anyone who comes along and says, “You know, it’s normal that you are suffering. Life is suffering,” is doing a quite unusual thing in our culture, which is so much about optimism. It sounds grim; it is in fact enormously consoling and alleviating and helpful, in a culture which is oppressive in its demands for perfection. So I think a certain kind of pessimistic realism — which is totally compatible with hope, totally compatible with laughter, good humor, a sense of fun — it doesn’t have to be dour.

如果有人站出来说:"你知道,你在受苦,这很正常。生活就是苦难",在我们的文化中,这是很不寻常的一件事,因为我们的文化非常讲究乐观主义。这听起来很残酷,但在一个要求完美的压抑文化中,这实际上是极大的安慰、缓解和帮助。因此,我认为某种悲观的现实主义--它与希望完全兼容,与欢笑、幽默、趣味完全兼容--并不一定是沉闷的。

Tippett:

蒂皮特 It’s how comedy and tragedy belong together.

喜剧和悲剧就是这样结合在一起的。

de Botton:

德波顿 Right. Exactly. So I’m a great fan of gallows humor. We’re all on our way to the gallows in one way or another, and we can hug and give each other laughs and point out the more pleasant sides as we head towards the scaffold.

没错。没错所以我是绞刑架幽默的忠实粉丝我们或多或少都在走向绞刑架的路上,在走向绞刑架的过程中,我们可以拥抱在一起,互相取笑,指出对方更讨人喜欢的一面。

Tippett:

蒂皮特 [laughs] That may be your last word. I just want to ask you, when we first began to speak about On Love, which you wrote — which was published when you were 23 in the late ‘90s — you’ve now been married for over a dozen years. What did you really not know? And that book was so wise. And in fact, that book that you published when you were 23, On Love, really presented a lot of the themes that you’ve carried forward in time. But I do wonder what you really did not know; what you’ve learned; what you continue to learn about love at this stage in your life.

[笑] 这可能是你最后一个字了。我只想问你,当我们第一次开始谈论你写的《论爱》时--这本书是在 90 年代末你 23 岁时出版的--你现在已经结婚十几年了。你到底不知道什么?那本书太有智慧了。事实上,你在 23 岁时出版的那本书《论爱》,确实提出了很多你一直在思考的主题。但我想知道,在你人生的这个阶段,你真正不知道的是什么;你学到了什么;你还在继续学习关于爱的什么。

de Botton:

德波顿 I genuinely thought at that time that problems in love are the result of being with people who are, in one way or another, defective. And in 2002, this belief was severely tested, in that I met someone who was really absolutely wonderful in every way. And through much effort, I pursued her and eventually married her and discovered something very surprising. She was great in a million ways. She was very right. And yet, oddly, there were all sorts of problems.

当时我真的认为,爱情中的问题都是和那些在某一方面有缺陷的人在一起造成的。2002 年,我的这种想法受到了严峻的考验,因为我遇到了一个各方面都非常优秀的人。经过一番努力,我追到了她,并最终和她结了婚。她在很多方面都很棒。她非常正确。然而,奇怪的是,我遇到了各种各样的问题。

And I think it’s been the path that I’ve been on, to realize that those problems had nothing to do with her being a deficient person or indeed with me being a horribly deficient person. They were to do with the challenges of being a human being trying to relate to another human being in a loving relationship; that I was encountering some endemic issues that every couple, however well-matched — and there is no such thing as a perfect match, but however well-matched, every couple will encounter these problems; that love is something we have to learn and we can make progress with, and that it’s not just an enthusiasm, it’s a skill, and it requires forbearance, generosity, imagination, and a million things besides.

我认为这是我一直在走的路,我认识到这些问题与她是一个有缺陷的人无关,也与我是一个可怕的有缺陷的人无关。我遇到了一些普遍存在的问题,每对夫妻,无论多么般配--没有完美的匹配,但无论多么般配,都会遇到这些问题;爱是我们必须学习的东西,我们可以在爱的道路上取得进步,它不仅仅是一种热情,更是一种技巧,它需要忍耐、慷慨、想象力,以及无数其他的东西。

And we must fiercely resist the idea that true love must mean conflict-free love; that the course of true love is smooth. It’s not. The course of true love is rocky and bumpy at the best of times. That’s the best we can manage, as the creatures we are. It’s no fault of mine or no fault of yours; it’s to do with being human. And the more generous we can be towards that flawed humanity, the better chance we’ll have of doing the true hard work of love.

我们必须坚决抵制这样的想法,即真爱就一定是没有冲突的爱;真爱的过程是一帆风顺的。事实并非如此。真爱的道路在最好的情况下也是坎坷不平的。作为生物,我们只能做到这一点。这不是我的错,也不是你的错;这是人之常情。我们对有缺陷的人性越宽容,我们就越有机会去做真正艰苦的爱的工作。

[music: “Semblance” by Auditory Canvas]

[音乐: Auditory Canvas的 "Semblance"]

Tippett:

蒂皮特Alain de Botton is the founder and chairman of The School of Life. His books include Religion for Atheists and How Proust Can Change Your Life. He’s also published many books as part of The School of Life’s offerings — there is a chapbook, for example, created from his essay “Why You Will Marry the Wrong Person.”

阿兰-德波顿是生命学院的创始人和主席。他的著作包括《无神论者的宗教》和《普鲁斯特如何改变你的生活》。他还出版了许多书籍,作为生命学院产品的一部分--例如,有一本小册子就是根据他的散文 "为什么你会嫁错人 "创作的。

[music: “Semblance” by Auditory Canvas]

[音乐: Auditory Canvas的 "Semblance"]

The On Being Project is: Chris Heagle, Lily Percy, Laurén Drommerhausen, Erin Colasacco, Eddie Gonzalez, Lilian Vo, Lucas Johnson, Suzette Burley, Zack Rose, Colleen Scheck, Christiane Wartell, Julie Siple, Gretchen Honnold, Jhaleh Akhavan, Pádraig Ó Tuama, Ben Katt, Gautam Srikishan, and Lillie Benowitz.

存在项目Chris Heagle、Lily Percy、Laurén Drommerhausen、Erin Colasacco、Eddie Gonzalez、Lilian Vo、Lucas Johnson、Suzette Burley、Zack Rose、Colleen Scheck、Christiane Wartell、Julie Siple、Gretchen Honnold、Jhaleh Akhavan、Pádraig Ó Tuama、Ben Katt、Gautam Srikishan 和 Lillie Benowitz。

The On Being Project is located on Dakota land. Our lovely theme music is provided and composed by Zoë Keating. And the last voice that you hear, singing at the end of our show, is Cameron Kinghorn.

本体项目位于达科他州的土地上。我们动听的主题音乐由佐伊-基廷(Zoë Keating)提供和创作。节目最后的歌声由卡梅隆-金霍恩(Cameron Kinghorn)演唱。

On Being is an independent, nonprofit production of The On Being Project. It is distributed to public radio stations by WNYC Studios. I created this show at American Public Media.

On Being 是 The On Being Project 的独立、非营利性节目。它由 WNYC Studios 向公共广播电台发行。我在美国公共媒体制作了这个节目。

Our funding partners include:

我们的资助合作伙伴包括

The Fetzer Institute, helping to build the spiritual foundation for a loving world. Find them at fetzer.org.

费策研究所(The Fetzer Institute),帮助建立一个充满爱的世界的精神基础。请访问 fetzer.org。

Kalliopeia Foundation, dedicated to reconnecting ecology, culture, and spirituality; supporting organizations and initiatives that uphold a sacred relationship with life on Earth. Learn more at kalliopeia.org.

卡利奥佩亚基金会(Kalliopeia Foundation),致力于重新连接生态、文化和灵性;支持维护与地球生命之间神圣关系的组织和倡议。了解更多信息,请访问 kalliopeia.org。

The George Family Foundation, in support of the Civil Conversations Project.

乔治家庭基金会,支持公民对话项目。

The Osprey Foundation, a catalyst for empowered, healthy, and fulfilled lives.

奥斯皮尔基金会,一个促进有能力、健康和充实生活的机构。

And the Lilly Endowment, an Indianapolis-based, private family foundation, dedicated to its founders’ interests in religion, community development, and education.

而礼来基金会是一家总部位于印第安纳波利斯的私人家族基金会,致力于其创始人在宗教、社区发展和教育方面的兴趣。

Books & Music

Recommended Reading

推荐阅读

The On Being Project is an affiliate partner of Bookshop.org and Amazon.com. Any earnings we receive through these affiliate partnerships go into directly supporting The On Being Project.

本体项目是 Bookshop.org 和 Amazon.com 的联盟合作伙伴。我们通过这些联盟合作获得的任何收入都将直接用于支持 "存在即项目"。

Reflections

思考