Hemant Rathod, an Indian executive, was sipping tea in a conference room Friday morning in Delhi, about to send a long email to his team, when his computer went haywire.

The HP laptop suddenly said it needed to restart. Then the screen turned blue. He tried in vain to reboot. Within 10 minutes, the screens of three other colleagues in the room turned blue too.

“I had taken so much time to draft that email,” Rathod, a senior vice president at Pidilite Industries 500331 0.22%increase; green up pointing triangle, a construction-materials company, said by phone half a day later, still carrying his dead laptop with him. “I really hope it’s still there so I don’t have to write it again.”

The outage, one of the most momentous in recent memory, crippled computers worldwide and drove home the brittleness of the interlaced global software systems that we rely on.

Triggered by an errant software update from the cybersecurity company CrowdStrike CRWD -11.10%decrease; red down pointing triangle

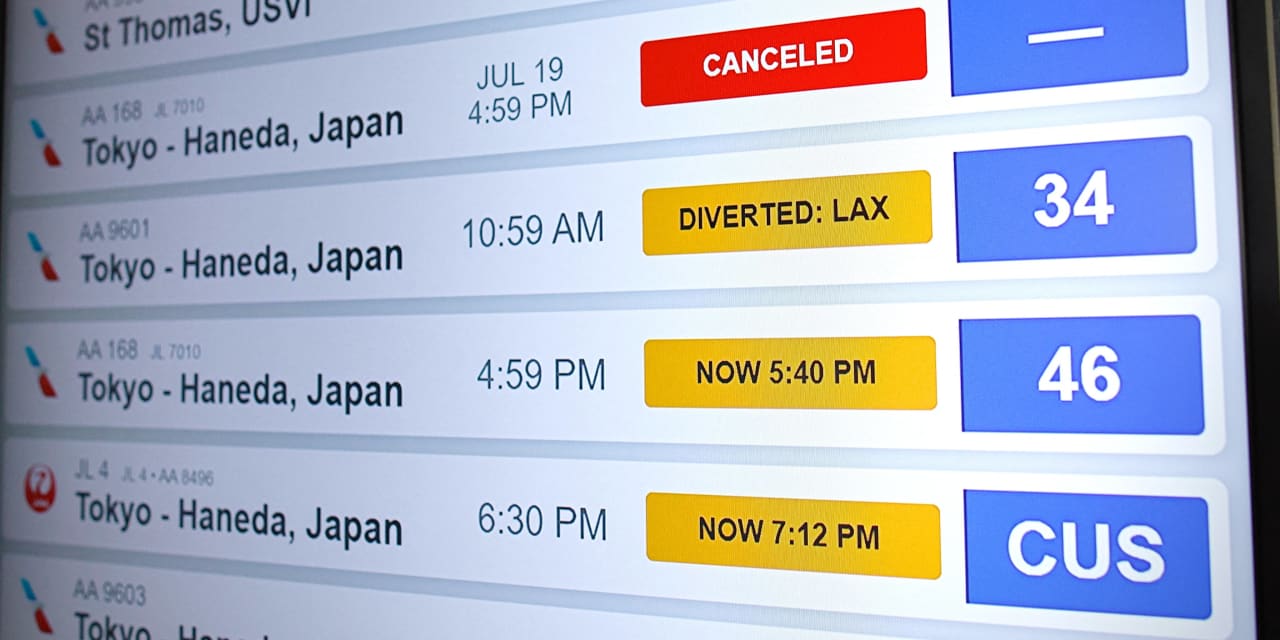

Over the course of less than 80 minutes before CrowdStrike stopped it, the update sailed into Microsoft Windows-based computers worldwide, turning corporate laptops into unusable bricks and paralyzing operations at restaurants, media companies and other businesses. U.S. 911 call centers were disrupted, Amazon.com employees’ corporate email system went on the fritz, and tens of thousands of global flights were delayed or canceled.

“In my 30-year technical career, this is by far the biggest impact I’ve ever seen,” said B.J. Moore, chief information officer for the Renton, Wash.-based healthcare system Providence, whose hospitals struggled to access patient records, perform surgeries and conduct CT scans.

Fixing the problem involved technical steps that confounded many users who aren’t tech-savvy. Some corporate IT departments were still working to unfreeze computer systems late on Friday. CrowdStrike said the outage wasn’t a cyberattack.

Adding to the chaos—and further underlining the vulnerability of the global IT system—a separate problem hit Microsoft’s Azure cloud computing system on Thursday shortly before the CrowdStrike glitch, causing an outage for customers including some U.S. airlines and users of Xbox and Microsoft 365.

The CrowdStrike problem laid bare the risks of a world in which IT systems are increasingly intertwined and dependent on myriad software companies—many not household names. That can cause huge problems when their technology malfunctions or is compromised. The software operates on our laptops and within corporate IT setups, where, unknown to most users, they are automatically updated for enhancements or new security protections.

In a 2020 hack, Russian perpetrators inserted malicious code into updates of SolarWinds software in a way that compromised a swath of the U.S. government and scores of private companies.

The rising frequency and impact of cyberattacks, including ones that insert damaging ransomware and spyware, have helped fuel the growth of CrowdStrike and such competitors as Palo Alto Networks and SentinelOne in recent years. CrowdStrike’s annual revenue has grown 12-fold over the past five years to over $3 billion.

But cybersecurity software such as CrowdStrike’s can be especially disruptive when things go wrong because it must have deep access into computer systems to rebuff malicious attacks.

Not all updates happen automatically, and computer attacks often occur because people or businesses are slow to adopt patches sent by software companies to fix vulnerabilities—in essence, failing to take the medicine the doctors prescribe. In this case, the medicine itself hurt the patients.

The global outage began with an update of a “channel file,” a file containing data that helps CrowdStrike’s software neutralize cyber threats, CrowdStrike said. The update was timestamped 4:09 a.m. UTC—just after midnight in New York and around 9:30 a.m. in India.

That update caused CrowdStrike’s software to crash the brains of the Windows operating system, known as the kernel. Restarting the computer simply caused it to crash again, meaning that many users had to surgically remove the offending file from each affected computer.

The nature of the patch meant that the impact was uneven, with people in the same office even experiencing the outage very differently. Apple Macs, which don’t use the affected Windows software, were OK, and servers and PCs that weren’t on and internet-connected didn’t receive the toxic update.

CrowdStrike soon realized something was amiss and the update to the file was rolled back 78 minutes later. That meant it wouldn’t affect computers that were off or in sleep mode during that period. But for many of those that were switched on, the damage was done.

In a blog post, CrowdStrike told those users to boot into the Windows “safe mode,” delete the offending file—called C-00000291*.sys—and reboot.

IT teams often can fix problems on employees’ computers using remote-access software—tools that became especially common during the work-from-home boom of the pandemic. But for laptops and other PCs that approach doesn’t work if the machines can’t restart. For those systems, CrowdStrike’s fix had to be done in person—either by a tech-support person on site, or by a regular employee trying to apply the instructions.

Moore, the Washington state healthcare CIO, was away on vacation and initially wasn’t worried when emails about malfunctioning computer applications started landing in his inbox Thursday night.

But by 11 p.m. Pacific time, he had learned that the outage had engulfed the nonprofit health system’s approximately 50 hospitals and 1,000 clinics across seven states. Hundreds of IT employees began deploying patches, which required manual remediation, he said.

Some of the system’s affected computers and devices were fixed by 6 a.m., and most were humming again by 10 a.m. “It will be the end of the day before we get it all done,” Moore said Friday morning.

As companies were grappling with the impact, CrowdStrike’s co-founder and chief executive officer, George Kurtz, was on TV trying to reassure customers—and shareholders—looking haggard after a long night.

“We identified this very quickly and rolled back this particular content file,” Kurtz said in a CNBC interview about nine hours after the faulty update. “Some systems may not fully recover, and we’re working individually with each and every customer to make sure that we can get them up and running and operational,” he added.

The time frame for the recovery could be hours or “a bit longer,” he said. Kurtz said on X that the outage wasn’t “a security incident or cyberattack.”

SHARE YOUR THOUGHTS

How did the tech outage affect you? Join the conversation below.

Microsoft CEO Satya Nadella took to X to offer his own reassurance that the company was working closely with CrowdStrike to bring systems back online. Tesla CEO Elon Musk responded, “This gave a seizure to the automotive supply chain,” and later said, “We just deleted CrowdStrike from all our systems.”

In the U.S., air travel chaos spilled into a second day Saturday as some airlines struggled to get operations back on track, while others started to return to normal. Over 1,200 U.S. flights had been scrapped as of midday Saturday in addition to the 3,400 that were canceled Friday according to FlightAware, a flight tracking site.

Delta Air Lines has been the hardest hit, scrubbing over a third of its flights Friday with mounting cancellations Saturday. Delta executives wrote in an internal memo Friday that a significant number of the airline’s operating applications run on Windows. Most of those had been restored, but a crew tracking-related tool was taking longer to process the high volume of changes. The carrier told pilots in a separate Saturday update that a large volume of open trips needed crews and the airline was working to prevent planes from backing up on the ground at its Atlanta hub.

For Rathod, the senior vice president at Pidilite, the travails didn’t end with his potentially lost email. After switching to his iPad to keep working, he had to rush to the airport for a flight—only to find long lines and flummoxed security staff checking boarding passes manually. Flight information screens weren’t working, so he had to find airline staff to direct him to the right gate.

“It was a mess at Delhi airport,” Rathod said. “How can we depend so much on one company?”

Tom Dotan and Robert McMillan contributed to this article.

Write to Asa Fitch at asa.fitch@wsj.com, Sam Schechner at Sam.Schechner@wsj.com and Sarah E. Needleman at Sarah.Needleman@wsj.com

Copyright ©2024 Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved. 87990cbe856818d5eddac44c7b1cdeb8