流行明星排名:埃米纳姆的回归和对取消文化的迷恋让评论家困惑

It all starts with a crystal.

一切都始于一颗水晶。

To make the solar cells that are projected to become the world’s biggest source of electricity by 2031, you first melt down sand until it looks like chunks of graphite. Next, you refine it until impurities have been reduced to just one atom out of every 100 million — a form of elemental silicon known as polysilicon. It’s so vital to the production of solar panels that it can be likened to crude oil’s role in making gasoline. The polysilicon is then drawn out into a vast crystal, resembling a Jeff Koons steel sculpture of a sausage, before being sliced into salami-thin wafers. These are then treated, printed with electrodes, and finally sandwiched between glass.

要制造预计到 2031 年将成为世界最大电力来源的太阳能电池,首先需要将沙子熔化,直到它看起来像石墨块。接下来,进行精炼,直到杂质减少到每一亿个原子中仅有一个——这种形式的元素硅被称为多晶硅。它对太阳能电池板的生产至关重要,可以比作原油在制造汽油中的作用。然后将多晶硅拉成一个巨大的晶体,类似于杰夫·昆斯的香肠钢雕塑,再切成薄如萨拉米的晶圆。接着对这些晶圆进行处理,印刷电极,最后夹在玻璃之间。

The basic process has changed little since the first cell was invented in 1954 by scientists at Bell Laboratories in New Jersey exploring whether silicon could be used to power computer processors. “It may mark the beginning of a new era,” The New York Times wrote at the time in a front-page article announcing the discovery, “leading eventually to the realization of one of mankind’s most cherished dreams — the harnessing of the almost limitless energy of the sun for the uses of civilization.”

自 1954 年新泽西州贝尔实验室的科学家发明第一个电池以来,基本过程变化不大,他们探索硅是否可以用于为计算机处理器供电。《纽约时报》当时在一篇头版文章中写道:“这可能标志着一个新时代的开始,最终实现人类最珍视的梦想之一——利用几乎无限的太阳能为文明服务。”

The seven decades since tell the remarkable story of how America squandered its invention of solar photovoltaics, or PV, to the point where it will never recover. As recently as 2010, a small town in central Michigan was the world’s biggest producer of solar polysilicon. Nowadays, the US is barely in the game, and more than 90% of the total comes from China. That country’s clean-technology exports “threaten to significantly harm American workers, businesses and communities,” President Joe Biden said May 14, announcing 50% tariffs on Chinese solar cells.

过去七十年讲述了美国如何浪费其太阳能光伏(PV)发明的非凡故事,以至于再也无法恢复。就在 2010 年,密歇根州中部的一个小镇是世界上最大的太阳能多晶硅生产商。如今,美国几乎不再参与这一领域,超过 90%的总量来自中国。乔·拜登总统在 5 月 14 日宣布对中国太阳能电池征收 50%的关税时表示,该国的清洁技术出口“威胁到美国工人、企业和社区的利益”。

Washington blames China’s dominance of the solar industry on what are routinely dubbed “unfair trade practices.” But that’s just a comforting myth. China’s edge doesn’t come from a conspiratorial plot hatched by an authoritarian government. It hasn’t been driven by state-owned manufacturers, subsidized loans to factories, tariffs on imported modules or theft of foreign technological expertise. Instead, it’s come from private businesses convinced of a bright future, investing aggressively and luring global talent to a booming industry — exactly the entrepreneurial mix that made the US an industrial powerhouse.

华盛顿将中国在太阳能行业的主导地位归咎于所谓的“ unfair trade practices”。但这只是一个安慰的神话。中国的优势并不是来自一个专制政府策划的阴谋。它并不是由国有制造商、对工厂的补贴贷款、对进口模块的关税或对外国技术专长的盗窃所推动的。相反,它来自于私营企业对光明未来的信心,积极投资并吸引全球人才进入一个蓬勃发展的行业——这正是使美国成为工业强国的企业家精神的结合。

The fall of America as a solar superpower is a tragedy of errors where myopic corporate leadership, timid financing, oligopolistic complacency and policy chaos allowed the US and Europe to neglect their own clean-tech industries. That left a yawning gap that was filled by Chinese start-ups, sprouting like saplings in a forest clearing. If rich democracies are playing to win the clean technology revolution, they need to learn the lessons of what went wrong, rather than just comfort themselves with fairy tales.

美国作为太阳能超级大国的衰落是一个错误的悲剧,短视的企业领导、胆怯的融资、寡头的自满和政策混乱使得美国和欧洲忽视了自己的清洁技术产业。这留下了一个巨大的空白,正是中国初创企业如同森林空地上的幼苗般填补了这一空白。如果富裕的民主国家想要在清洁技术革命中获胜,他们需要吸取教训,了解哪里出了问题,而不是仅仅用童话故事来安慰自己。

To understand what happened, I visited two places: Hemlock, Michigan, a tiny community of 1,408 people that used to produce about one-quarter of the world’s PV-grade polysilicon, and Leshan, China, which is now home to some of the world’s biggest polysilicon factories. The similarities and differences between the towns tell the story of how the US won the 20th century’s technological battle — and how it risks losing its way in the decades ahead.

为了理解发生了什么,我访问了两个地方:密歇根州的海莫克,一个只有 1,408 人的小社区,曾经生产全球约四分之一的光伏级多晶硅,以及中国的乐山,现在是一些世界最大多晶硅工厂的所在地。这两个城镇之间的相似与差异讲述了美国如何赢得 20 世纪的技术战斗——以及它如何在未来几十年中面临失去方向的风险。

If you own a mobile phone, a computer, a car, or a home appliance, it’s likely there’s a little bit of Hemlock in your home right now. Hemlock Semiconductor Corp. produces about one-third of the world’s chip-grade polysilicon, which finds its way into almost every electronic device on the planet. Solar polysilicon is simply the poor cousin of the stuff computer chips are made from: While impurities of one part in 100 million are considered acceptable for solar panels, microprocessors need to be pure to as much as one part in 10 trillion.

如果您拥有手机、电脑、汽车或家用电器,那么您家里很可能现在有一点毒芹。毒芹半导体公司生产全球约三分之一的芯片级多晶硅,这些多晶硅几乎进入了地球上每一款电子设备。太阳能多晶硅只是计算机芯片所用材料的低档表亲:对于太阳能电池板,100 百万分之一的杂质被认为是可接受的,而微处理器需要纯度高达 10 万亿分之一。

The constant stream of chemical tanker trucks going to and from the plant is the only sign that a vital node of the global economy is hidden among Hemlock’s soybean, corn and blueberry fields, dotted with red barns, clapboard homes and flagpoles. Two hours north of Detroit and inland from Lake Huron, its main street hosts a discount store, a coin-op laundry, a Ford dealership, a vet clinic, a handful of liquor stores and chain restaurants, a tavern and very little else.

化学油轮卡车不断进出工厂,是全球经济一个重要节点隐藏在 Hemlock 的大豆、玉米和蓝莓田中的唯一迹象,田间点缀着红色谷仓、木板房和旗杆。距离底特律以北两小时,远离休伦湖,主街上有一家折扣店、一家投币洗衣店、一家福特经销商、一家兽医诊所、几家酒类商店和连锁餐厅、一家酒馆,几乎没有其他设施。

It’s about as close to Middle America as you can get. Former President Donald Trump won surrounding Saginaw County, long a Democratic stronghold, by 1,074 votes in the 2016 presidential election. Four years later, Biden took it back on a margin of 303. Hemlock is part of Michigan’s 8th Congressional District, the pivot point of the entire US House of Representatives. Currently, exactly 217 seats are more Democrat-leaning, and 217 more Republican-leaning.

这几乎是你能接近中美洲的地方。前总统唐纳德·特朗普在 2016 年总统选举中以 1,074 票的优势赢得了周边的萨吉诺县,这里长期以来是民主党的坚固堡垒。四年后,拜登以 303 票的优势夺回了该地区。赫莫克是密歇根州第 8 国会选区的一部分,这是整个美国众议院的关键点。目前,正好有 217 个席位更倾向于民主党,另外 217 个席位更倾向于共和党。

Hemlock Semiconductor keeps a low profile in this rural area. Driving past stands of the hemlock pines that give the town its name, you’re almost at the gate of the roughly 800-acre (three-square-kilometer) site before you notice its distillation towers, warehouses and a low industrial hum. The company turned down Bloomberg’s requests to visit the facility or interview executives.

Hemlock Semiconductor 在这个乡村地区保持低调。驾车经过给小镇命名的铁杉树林时,您几乎到达这个大约 800 英亩(约三平方公里)场地的门口,才注意到它的蒸馏塔、仓库和低沉的工业嗡嗡声。该公司拒绝了彭博社对参观设施或采访高管的请求。

Hemlock Semiconductor sits amidst farmland and forest west of Saginaw, Michigan.

毒死蜱半导体位于密歇根州萨吉诺西部的农田和森林之间。

Photographer: David Fickling/Bloomberg

摄影师:大卫·菲克林/彭博社

People in town appreciate the semiconductor factory as a provider of more than 1,300 jobs, alongside funding for the town fair and school board — even if it’s always been a bit opaque. Katherine Ellison, a local historian, grew up in the 1980s two roads across from the plant, nicknamed “The City in the Woods” by her friends. “You’d kind of stumble upon this huge, lit-up structure at night,” she told me. “People who weren’t from here would ask, “What is that?”

镇上的人们很感激这家半导体工厂提供了超过 1,300 个工作岗位,并为镇上的集市和学区提供资金——尽管它一直有些不透明。当地历史学家凯瑟琳·埃利森在 1980 年代成长于工厂对面的两条街道,她的朋友们称这里为“森林中的城市”。“你晚上会偶然发现这个巨大的、亮着灯的建筑,”她告诉我。“不来自这里的人会问,‘那是什么?’”

Operations started long before solar power was taken seriously. The year was 1961, a time when the founders of Intel Corp. were looking at using polysilicon to build the first integrated circuits for use in the Apollo space program. That seemed an ideal business for Dow Corning, a long-standing joint venture between Dow Chemical Co. and Corning Inc. specializing in silicon-based chemicals such as glues, sealants and breast implants.

运营开始于太阳能被认真对待之前的很久。那是 1961 年,当时英特尔公司的创始人正在考虑使用多晶硅来制造用于阿波罗太空计划的第一个集成电路。这似乎是陶氏康宁公司的理想业务,陶氏康宁是陶氏化学公司与康宁公司的长期合资企业,专注于硅基化学品,如胶水、密封剂和乳房植入物。

Dow had established itself in the 1890s in nearby Midland to take advantage of rich underground deposits of brine that could be refined into useful chemicals. The trains rattling back and forth there upset the delicate polysilicon purification process, so a new plant was established on isolated farmland in Hemlock, 14 miles (22.5 kilometers) to the south.

道公司在 1890 年代在附近的米德兰建立,以利用丰富的地下盐水储备,这些盐水可以提炼成有用的化学品。来回穿梭的火车扰乱了精细的多晶硅净化过程,因此在南方 14 英里(22.5 公里)的偏远农田上建立了一座新工厂。

It’s never been an easy business. Moore’s Law — the celebrated rule of innovation that turned computers from room-sized, costly devices in the 1950s into affordable microchips that can sit on a fingertip — also required constant reductions in the costs and volumes of polysilicon in use, making it hard for companies to make consistent profits. “The purer it is, the less you need,” Denise Beachy, Hemlock’s president from 2014 to 2016, told me.

这从来不是一项简单的业务。摩尔定律——这一备受推崇的创新法则将 1950 年代的房间大小、昂贵的计算机转变为可以放在指尖上的经济实惠的微芯片——也要求不断降低使用的多晶硅的成本和数量,这使得公司很难实现稳定的利润。“越纯,需求越少,”2014 年至 2016 年间的海姆洛克总裁丹尼斯·比奇告诉我。

As far back as 1984, a study for the US Department of Energy noted that Hemlock was “an old, high-cost plant” where Dow Corning was “reluctant to invest.” With the venture unwilling to spend money, fresh capital was brought in the same year by selling about one-third of the factory’s equity to Japan’s Shin-Etsu Handotai Co. and Mitsubishi Materials Corp.

早在 1984 年,美国能源部的一项研究指出,Hemlock 是“一家老旧、高成本的工厂”,而道康宁“不愿意投资”。由于该合资企业不愿花钱,同年通过将工厂约三分之一的股权出售给日本的信越半导体公司和三菱材料公司引入了新资本。

Things started to change around the year 2000, as rising concerns about climate change coincided with a surge in oil prices and the prospect of subsidies for renewables. Solar panels were traditionally so costly they were only used for highly specialized applications such as space probes, as well as watches and pocket calculators that only sip power. Suddenly in the early 2000s, solar started to look like a competitive way of producing energy.

事情在 2000 年左右开始发生变化,随着对气候变化的关注加剧,油价飙升以及可再生能源补贴的前景出现。太阳能电池板传统上成本高昂,仅用于空间探测器等高度专业化的应用,以及仅需少量电力的手表和口袋计算器。突然在 2000 年代初,太阳能开始看起来像是一种具有竞争力的能源生产方式。

As a result, PV-grade polysilicon — made until then from material rejected by chipmakers — seemed like it might become a valuable commodity in its own right. Almost overnight, it went from a backwater to a boom industry. The growth has yet to stop. Since 2005, annual installations of solar panels have increased at an average annual rate of about 44%. This year, the capacity of new modules installed globally every three days is roughly equivalent to what existed in the entire world at the end of 2005.

因此,光伏级多晶硅——直到那时由芯片制造商拒绝的材料制成——似乎可能成为一种有价值的商品。几乎一夜之间,它从一个冷门行业变成了一个繁荣的产业。增长尚未停止。自 2005 年以来,太阳能电池板的年安装量以约 44%的年均增长率增加。今年,每三天在全球安装的新模块的容量大致相当于 2005 年底全球所拥有的总容量。

Hemlock initially surfed this wave. In 2005, it announced a $400 million to $500 million plan to increase production at the plant by half. Eighteen months later, it promised $1 billion more to add a further 90%. One more billion was announced amid the 2008 financial crisis, along with yet another $1.2 billion for a separate plant in Clarksville, Tennessee.

Hemlock 最初乘风而起。2005 年,它宣布了一项 4 亿到 5 亿美元的计划,以将工厂的产量提高一半。十八个月后,它承诺再投资 10 亿美元,以增加进一步的 90%。在 2008 年金融危机期间,又宣布了 10 亿美元的投资,以及另外 12 亿美元用于田纳西州克拉克斯维尔的另一座工厂。

Those numbers sound big — but they were insufficient to keep up with demand.

这些数字听起来很大——但它们不足以满足需求。

There are a few reasons for that. First, Hemlock was owned by a joint venture between two American and two Japanese chemical companies, which between them produce everything from fiber optic cables to smartphone glass, plastics to insecticides, pill casings to machine tools and gold bullion. Such setups are notorious for complexity, which can undermine their ability to adapt quickly to changing conditions. Any fresh spending needed to get signed off by four corporate boards, none of whom saw solar poly as a priority.

这有几个原因。首先,Hemlock 由两家美国和两家日本化工公司组成的合资企业拥有,这些公司生产从光纤电缆到智能手机玻璃、塑料到杀虫剂、药丸外壳到机床和黄金条等各种产品。这种结构以复杂著称,这可能削弱它们快速适应变化条件的能力。任何新的支出都需要得到四个公司董事会的批准,而这些董事会都没有将太阳能多晶硅视为优先事项。

Making matters worse was the fact that, when solar power started to take off in the late 1990s, Hemlock’s main shareholder Dow Corning was in the middle of a decade of bankruptcy protection — the result of lawsuits from women who claimed to have been harmed by its silicone breast implants.

更糟糕的是,当太阳能在 1990 年代末开始兴起时,海莫克的主要股东陶氏康宁正处于长达十年的破产保护期——这源于一些女性提起的诉讼,她们声称受到其硅胶乳房植入物的伤害。

Another factor was energy. As much of 40% of the cost of producing polysilicon is power, and the Hemlock factory is the biggest single-site consumer of electricity in Michigan — a remarkable statistic, when you consider the state also includes the immense General Motors Co. and Ford Motor Co. factories in Detroit.

另一个因素是能源。生产多晶硅的成本中多达 40%是电力,而 Hemlock 工厂是密歇根州最大的单一地点电力消费者——这是一个显著的统计数据,考虑到该州还包括位于底特律的庞大的通用汽车公司和福特汽车公司工厂。

Local electricity costs are relatively high. The 2008 expansion in Hemlock only went ahead after the state’s governor Jennifer Granholm — now President Biden’s secretary of energy — signed a bill giving the facility tax credits to protect it from electricity price hikes. Clarksville was proposed for a new plant because of its access to cheap power from the Tennessee Valley Authority, a New Deal-era hydroelectric project.

当地电力成本相对较高。2008 年,Hemlock 的扩张只有在州长 Jennifer Granholm——现任拜登总统的能源部长——签署了一项法案,给予该设施税收抵免以保护其免受电价上涨的影响后才得以进行。Clarksville 因其能够获得来自田纳西河谷管理局的廉价电力而被提议建设新厂,该项目是新政时代的水电项目。

Beyond all that, though, the reluctance to invest more aggressively was driven by the conviction that polysilicon was, and would always be, a cozy oligopoly. Until the mid-2000s, the raw material for all the chips and solar panels on the planet was produced at just 10 facilities in the US, Europe and Japan. They were under the control of seven companies, of which Hemlock was comfortably the largest. This provided the kind of cartel-like price security enjoyed by the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC).

尽管如此,更加积极投资的犹豫是由于对多晶硅的信念,即它是并将始终是一个舒适的寡头垄断。直到 2000 年代中期,全球所有芯片和太阳能电池板的原材料仅在美国、欧洲和日本的 10 个工厂生产。这些工厂由七家公司控制,其中 Hemlock 是最大的。这提供了类似于石油输出国组织(OPEC)所享有的卡特尔式价格安全。

The solar panel-makers who depended on the seven companies for their polysilicon hated the situation — as did anyone who wanted to see the costs of solar power fall and its scale increase. “The supply of feedstock has lagged far behind the demands of the industry,” lamented one 2007 report on the sector, which blamed the shortage on oligopolistic behavior by big producers. As a result, all hope that solar power might help the world avert disastrous global warming seemed futile. In an influential 2006 report for the UK government, the economist Nicholas Stern predicted it would take decades for renewable power to become competitive with fossil fuels.

依赖这七家公司提供多晶硅的太阳能电池板制造商对这种情况感到厌恶——任何希望看到太阳能成本下降和规模扩大的人也是如此。“原材料的供应远远落后于行业的需求,”一份 2007 年的行业报告感叹道,该报告将短缺归咎于大型生产商的寡头行为。因此,所有希望太阳能能够帮助世界避免灾难性全球变暖的希望似乎都是徒劳的。在一份对英国政府具有影响力的 2006 年报告中,经济学家尼古拉斯·斯特恩预测,可再生能源要与化石燃料竞争需要几十年时间。

This didn’t bother the polysilicon producers, who were running at full capacity and enjoying scarcity that allowed them to drive up prices for consumers. The result was a fatal complacency. “Hemlock is extraordinarily profitable,” Jim Flaws, Corning’s chief financial officer, boasted in a 2009 call with investors.

这并没有困扰多晶硅生产商,他们满负荷运转,享受着稀缺性,使他们能够提高消费者的价格。结果是致命的自满。“海姆洛克的利润极其丰厚,”康宁的首席财务官吉姆·弗劳斯在 2009 年与投资者的电话会议中自豪地说道。

Things were about to change drastically.

事情即将发生剧变。

SunEdison (US) 阳光电源(美国)

Cost 成本

Tokuyuma (Japan) 德久山(日本)

$25/kg $25/千克

Hemlock (US) 毒死蜱 (美国)

Hankook (South Korea) 韩华(韩国)

Wacker (Germany) 瓦克(德国)

20

OCI (South Korea, Malaysia)

OCI(韩国,马来西亚)

Hanwha (South Korea) 汉华(韩国)

REC (US) REC(美国)

15

10

5

0

0

100K 10 万

200K 20 万

300K 30 万

400K 40 万

500K 50 万

Capacity, metric tons 容量,公吨

Note: Data from 2013 through mid-2024 except for Asia Silicon (2017–24), China Silicon (2013–19), East Hope (2018–24), Hankook (2014–18), Hanwha (2015–19), Hemlock (2013–20, 2023–24), REC (2013–19), SunEdison (2013–17), Tokuyuma (2013–14), Tongwei (2016–24).

Sources: Bloomberg; BloombergNEF

Chinese manufacturers 中国制造商

Non-Chinese manufacturers

非中国制造商

Cost 成本

$25/kg $25/千克

China Silicon 中国硅业

20

Xinte 新特

Daqo 大阔

15

GCL

Tongwei 通威

Asia Silicon 亚洲硅业

10

5

0

0

100K 10 万

200K 20 万

300K 30 万

400K 40 万

500K 50 万

Capacity, metric tons 容量,公吨

Note: Data from 2013 through mid-2024 except for Asia Silicon (2017–24), China Silicon (2013–19), East Hope (2018–24), Hankook (2014–18), Hanwha (2015–19), Hemlock (2013–20, 2023–24), REC (2013–19), SunEdison (2013–17), Tokuyuma (2013–14), Tongwei (2016–24).

Sources: Bloomberg; BloombergNEF

Chinese manufacturers 中国制造商

Non-Chinese manufacturers

非中国制造商

Cost 成本

$25/kg $25/千克

Hemlock 毒芹

20

Wacker 瓦克

15

10

Xinte 新特

Tongwei 通威

Daqo 大阔

5

GCL

0

0

100K 10 万

200K 20 万

300K 30 万

400K 40 万

500K 50 万

Capacity, metric tons 容量,公吨

Note: Data from 2013 through mid-2024 except for Asia Silicon (2017–24), China Silicon (2013–19), East Hope (2018–24), Hankook (2014–18), Hanwha (2015–19), Hemlock (2013–20, 2023–24), REC (2013–19), SunEdison (2013–17), Tokuyuma (2013–14), Tongwei (2016–24).

Sources: Bloomberg; BloombergNEF

Note: Data from 2013 through mid-2024 except for Asia Silicon (2017–24), China Silicon (2013–19), East Hope (2018–24), Hankook (2014–18), Hanwha (2015–19), Hemlock (2013–20, 2023–24), REC (2013–19), SunEdison (2013–17), Tokuyuma (2013–14), Tongwei (2016–24).

注意:数据来自 2013 年至 2024 年中期,亚洲硅业(2017–24)、中国硅业(2013–19)、东希望(2018–24)、韩华(2014–18)、汉能(2015–19)、海默克(2013–20,2023–24)、REC(2013–19)、阳光电源(2013–17)、德高(2013–14)、通威(2016–24)除外。

In China’s southwestern Sichuan province in the mid-2000s, Liu Hanyuan was looking for new investment opportunities. He was born to a peasant family in Meishan, a small city on the broad banks of the Min river. After leaving school in the early 1980s — at a time when Deng Xiaoping’s reforms were starting to allow entrepreneurship in the state-controlled agriculture sector — he invented a mesh cage that could be suspended in fast-flowing water to farm fish and borrowed $69 (500 yuan) from his father to commercialize it.

在中国西南的四川省,刘汉元在 2000 年代中期寻找新的投资机会。他出生于眉山的一个农民家庭,眉山是一个位于岷江宽阔河岸的小城市。在 1980 年代初离开学校时——那时邓小平的改革开始允许国有农业部门的创业——他发明了一种可以悬挂在急流中养鱼的网箱,并向父亲借了 69 美元(500 元)来进行商业化。

The technique was a success. Looking to the next opportunity, Liu started producing fish food in a kitchen hand-grinder to sell to other farmers. That did even better: There was a huge market for such pellets as aquaculture production grew at double-digit rates throughout the 1980s and 1990s to meet China’s seemingly insatiable appetite for seafood. By 2002, Forbes magazine named Liu the country’s ninth-richest person, and he became a regular delegate to the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference, a quasi-parliament composed of the politically-connected great and good. His company, Tongwei Co., posted $1.5 billion (10 billion yuan) in revenue in 2008.

该技术取得了成功。展望下一个机会,刘开始在厨房手动研磨机中生产鱼饲料,出售给其他农民。这一做法更为成功:随着水产养殖生产在 1980 年代和 1990 年代以两位数的速度增长,市场对这种颗粒饲料的需求巨大,以满足中国对海鲜的似乎无止境的需求。到 2002 年,《福布斯》杂志将刘评选为中国第九富豪,他成为中国人民政治协商会议的常任代表,该会议是由政治关系密切的杰出人士组成的准议会。刘的公司通威股份在 2008 年的收入达到了 15 亿美元(100 亿元人民币)。

But a slowdown was coming. By the mid-2000s, almost all the water usable for fish farms had been exploited, and the newly-minted tycoon had to find alternative sources of growth. One happened to be downstream from Liu’s hometown, in Leshan.

但经济放缓即将到来。到 2000 年代中期,几乎所有可用于鱼塘的水源都已被开发,而这位新崛起的富翁必须寻找替代的增长来源。其中一个恰好位于刘的家乡下游,在乐山。

Leshan would be a nondescript Chinese city were it not for a vast Buddha statue and some of the world’s biggest polysilicon factories.

乐山将是一个不起眼的中国城市,如果不是因为一座巨大的佛像和一些世界上最大的多晶硅工厂。

Photographer: David Fickling/Bloomberg

摄影师:大卫·菲克林/彭博社

Like Hemlock, Leshan lies atop a prehistoric sea, making it rich in brine and a natural home for a chemicals industry. Unlike Hemlock, it is blessed with a superabundance of cheap electricity. Sichuan is where the tributaries of the Yangtze tumble down from the foothills of the Himalayas in a precipitous drop, before starting a meander to the sea. Leshan itself, whose population of 1.5 million makes it a small town in Chinese terms, is home to one of the world’s biggest Buddha statues. As tall as a 17-storey building, the seated figure was carved out of a cliff in the 8th century by monks, hoping it would protect river craft from the treacherous rapids where the Min and Dadu rivers mingle. The Three Gorges Dam, the world’s biggest hydroelectric project, is further downstream. It’s a lively but ramshackle city, steaming in Sichuan’s humid, rainy summer heat, with scarcely a glimpse of the sun on which Leshan’s solar industry depends.

乐山像毒芹一样,位于史前海洋之上,富含盐水,是化工产业的天然家园。与毒芹不同的是,它拥有丰富的廉价电力。四川是长江支流从喜马拉雅山脚下陡然下降后,开始蜿蜒流向大海的地方。乐山本身,人口 150 万,在中国算是一个小城镇,拥有世界上最大的佛像之一。这座高达 17 层楼的坐佛雕刻于 8 世纪,由僧侣们从悬崖中雕刻而成,期望它能保护河流上的船只免受岷江和大渡河交汇处的急流侵袭。三峡大坝,世界上最大的水电项目,位于下游。这里是一个热闹但破旧的城市,在四川潮湿、雨季的夏季炎热中蒸腾,几乎看不到乐山的太阳,而这正是乐山太阳能产业所依赖的。

In the early 2000s, Sichuan was producing far more electricity than local plants could consume. That made it an excellent site for the energy-hungry polysilicon business. Meanwhile, downriver from Leshan, a chemicals plant producing PVC plastic was looking for ways to utilize its waste materials. Liu, who’d been curious about the semiconductor industry for years, saw an opportunity to break the dominance of Western polysilicon producers while mopping up these chemical byproducts. He invested $428 million (3 billion yuan) in the facility in 2007 and then signed up Trina Solar Co., a US-listed panel maker with headquarters near Shanghai, as a cornerstone customer.

在 2000 年代初,四川的电力生产远远超过当地工厂的消费需求。这使得这里成为能源需求旺盛的多晶硅行业的理想地点。与此同时,在乐山下游,一家生产 PVC 塑料的化工厂正在寻找利用其废料的方法。刘对半导体行业一直充满好奇,他看到了打破西方多晶硅生产商主导地位的机会,同时处理这些化学副产品。他在 2007 年投资了 4.28 亿美元(30 亿元人民币)用于该设施,并随后与位于上海附近的美国上市面板制造商天合光能签署了基础客户协议。

He wasn’t the only one with that idea. China’s trade boom during the 2000s was driven by vast factories assembling electronics for foreign companies at rock-bottom prices. PV panel makers saw an opportunity to take advantage of globalization, in the same way that contract manufacturers like Taiwan-based Hon Hai Precision Industry Co., or Foxconn, were cornering the market in assembling iPhones.

他并不是唯一有这个想法的人。2000 年代,中国的贸易繁荣是由大量工厂以极低的价格为外国公司组装电子产品推动的。光伏面板制造商看到了利用全球化的机会,就像台湾的鸿海精密工业股份有限公司(富士康)在组装 iPhone 方面占据市场一样。

Like everyone else who was making solar panels, these companies quickly grew unhappy with the oligopoly producing polysilicon. With prices soaring in the late 2000s, there was good money to be made by anyone who could undercut Hemlock and its rivals.

像其他制造太阳能电池板的公司一样,这些公司很快对生产多晶硅的寡头垄断感到不满。随着 2000 年代末价格飙升,任何能够低于 Hemlock 及其竞争对手价格的人都能赚到丰厚的利润。

The result was a land grab. Small-scale, high-cost solar poly plants sprouted in towns and cities across China. At one point, the country had as many as 80 manufacturers, many of them with lax attitudes toward pollution. That was far more than the country, or the world, needed. In 2008,China had 20,000 tons of polysilicon production capacity and a further 80,000 under construction, according to government data. But just 4,000 tons were produced that year, indicating supply far in excess of demand.

结果是土地争夺战。小规模、高成本的太阳能多晶硅工厂在中国各地的城镇和城市中涌现。曾几何时,国内有多达 80 家制造商,其中许多对污染的态度较为宽松。这远远超过了国家或世界的需求。根据政府数据,2008 年,中国的多晶硅生产能力为 20,000 吨,还有 80,000 吨在建设中。但当年仅生产了 4,000 吨,表明供应远远超过需求。

A crash was inevitable. In the long hangover from the 2008 financial crisis, cash-strapped governments in Europe started pulling the subsidies they’d used to kickstart the continent’s solar industry in the earlier part of the decade. China’s polysilicon producers were high-cost and dependent on exports. All but the most efficient were closed. Even as demand from panel producers waned, more silicon flooded into the market as cash-strapped manufacturers sought to sell off their inventory at any price.

崩溃是不可避免的。在 2008 年金融危机后的漫长余波中,欧洲的财政紧张政府开始撤回他们在本十年早期用于启动大陆太阳能产业的补贴。中国的多晶硅生产商成本高昂且依赖出口。除了最有效率的企业外,其他几乎都关闭了。即使面板生产商的需求减弱,更多的硅仍然涌入市场,因为资金紧张的制造商试图以任何价格出售他们的库存。

Between August and December 2011, spot prices for solar poly roughly halved, from around $50 a kilogram to just over $25. That was already below the levels Hemlock considered reasonable. But a year later, they had fallen another 40%, to about $15. (Currently, they’re running below $6.) Major customers pulled their orders or went into bankruptcy. It looked like the solar boom was ending before it had even really begun.

在 2011 年 8 月至 12 月期间,太阳能多晶硅的现货价格大约减半,从每公斤约 50 美元降至略高于 25 美元。这已经低于 Hemlock 认为合理的水平。但一年后,价格又下降了 40%,降至约 15 美元。(目前,它们的价格低于 6 美元。)主要客户取消了订单或破产。看起来太阳能热潮在真正开始之前就已经结束。

Feasts and famines are processes as old as nature — and business. The rush to take advantage of new opportunities can resemble a stampede. When those resources are inevitably exhausted, not all who sought to exploit them will survive — but those who do will often be the leanest and fittest of the bunch.

盛宴与饥荒是与自然和商业一样古老的过程。抓住新机会的冲动可能像是一场狂奔。当这些资源不可避免地耗尽时,并不是所有试图利用它们的人都会生存下来——但那些生存下来的人往往是其中最精干和最强壮的。

Some thought the best defense against the solar boom and bust of the late 2000s was to quit polysilicon’s rollercoaster ride altogether. In Tempe, Arizona, First Solar Inc. focused on a promising alternative technology that printed a thin layer of a different semiconductor, cadmium telluride, onto glass. Another company, Solyndra Inc., had a similar idea, spraying a mixture of copper and several rare metals onto tubes, and received a $535 million loan guarantee from the US Department of Energy to scale up. Solyndra’s bankruptcy in September 2011 tainted the idea of federal support for the industry for years to come.

一些人认为,抵御 2000 年代末太阳能繁荣与萧条的最佳防御措施是完全放弃多晶硅的过山车之旅。在亚利桑那州的坦佩,第一太阳能公司专注于一种有前景的替代技术,在玻璃上打印一层不同半导体——碲化镉。另一家公司,Solyndra 公司,有类似的想法,将铜和几种稀有金属的混合物喷涂到管子上,并获得了美国能源部 5.35 亿美元的贷款担保以扩大规模。Solyndra 在 2011 年 9 月的破产使得联邦对该行业的支持理念在未来几年受到影响。

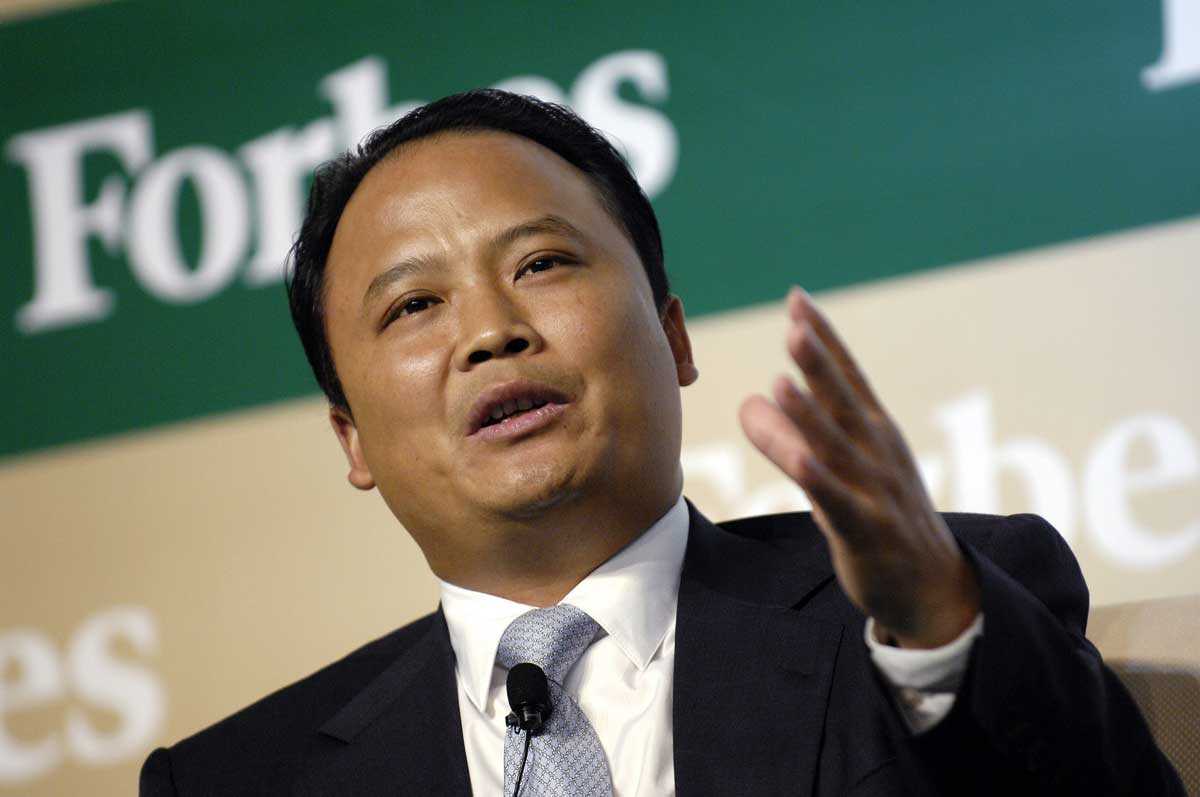

Liu Hanyuan, the fish farmer-turned-sun-king; Frank Asbeck, who triggered the 2012 solar trade war.

刘汉元,这位从鱼农转型的太阳能大亨;弗兰克·阿斯贝克,2012 年太阳能贸易战的引发者。

Photographers: Munshi Ahmed/Bloomberg and Ulrich Baumgarten via Getty Images

摄影师:Munshi Ahmed/Bloomberg 和 Ulrich Baumgarten via Getty Images

In Germany, the most prominent solar tycoon had other ideas. In just over a decade, Frank Asbeck had capitalized on Berlin’s renewable subsidies to build his manufacturer, SolarWorld AG, into a giant. That success turned him into a billionaire with a talent for self-promotion. He signed up Larry Hagman, the archetype of a Texas oilman in the 1980s soap opera Dallas, as a spokesman advocating for clean power. At one point, as GM circled bankruptcy in 2008, Asbeck even offered to buy its European Opel brand.

在德国,最杰出的太阳能大亨有其他想法。在短短十多年里,弗兰克·阿斯贝克利用柏林的可再生能源补贴,将他的制造商 SolarWorld AG 发展成一个巨头。这一成功使他成为一位拥有自我宣传才能的亿万富翁。他签下了拉里·哈格曼,这位 1980 年代肥皂剧《达拉斯》中德克萨斯州石油商的典型,作为倡导清洁能源的发言人。在 2008 年通用汽车濒临破产之际,阿斯贝克甚至提出收购其欧洲的欧宝品牌。

The chaos in the industry put Asbeck’s empire into jeopardy. SolarWorld was manufacturing its own panels at plants in Germany, South Korea, California and Oregon, at prices well above rival products coming out of China. But his US-based facilities gave Asbeck a card to play.

行业的混乱使阿斯贝克的帝国陷入危险。SolarWorld 在德国、韩国、加利福尼亚和俄勒冈的工厂生产自己的面板,价格远高于来自中国的竞争产品。但他在美国的设施为阿斯贝克提供了一个可以利用的筹码。

That allowed him to approach the Department of Commerce in October 2011 with a claim that China was not just selling cheap solar panels but dumping them on overseas markets at costs below what they were charging domestically. The US found in favor of SolarWorld six months later and imposed duties on China-made panels ranging as high as 250%. It would be the first of several waves of trade restrictions imposed against Chinese photovoltaics.

这使他能够在 2011 年 10 月向商务部提出索赔,称中国不仅在销售廉价太阳能电池板,还以低于国内价格的成本向海外市场倾销。六个月后,美国支持 SolarWorld,并对中国制造的电池板征收高达 250%的关税。这将是针对中国光伏产品实施的几轮贸易限制中的第一轮。

Claims of dumping are contentious and hugely consequential. They’re often brought by oligopolists who have had their comfortable hegemony disrupted by cheaper foreign rivals. If they win, they will gain government protection against their own inability to compete. Their domestic customers will typically take the other side of the debate and can be equally cynical: Buyers of solar panels simply want the cheapest modules they can get, regardless of the effect on local jobs and supply chains.

倾销的指控是有争议的,并且影响巨大。它们通常是由那些因廉价外国竞争对手而受到舒适霸权干扰的寡头提出的。如果他们胜诉,他们将获得政府对自身竞争无能的保护。国内客户通常会站在辩论的另一方,并且同样持怀疑态度:太阳能电池板的买家只想要他们能获得的最便宜的模块,而不考虑对当地就业和供应链的影响。

It’s conventional for insiders to act as if such decisions are made on sound objective criteria, but in truth it’s almost always a political mess built on a shaky foundation of low-quality data. When reviewing antidumping cases, “economists overwhelmingly reach the conclusion that the investigations are distorted and biased” in favor of manufacturers, according to one 2016 study of the solar dispute.

内部人士通常表现得好像这些决策是基于合理的客观标准,但实际上几乎总是建立在低质量数据的动摇基础上的政治混乱中。根据一项 2016 年关于太阳能争议的研究,“经济学家们压倒性地得出结论,调查存在扭曲和偏见”,偏向于制造商。

Meanwhile, the core questions are often almost impossible to answer. Is Tongwei’s cheap electricity from a state-owned utility a form of government subsidy? What about Hemlock’s tax credits protecting it from high power prices? Chinese businesses can often get cheap land in industrial parks, something that’s often considered a subsidy. But does zoning US land for industrial usage count as a subsidy too? Most countries have tax credits for research and development and compete to lower their corporate tax rates to encourage investment. The factor that determines whether such initiatives are considered statist industrial policy (bad), or building a business-friendly environment (good), is usually whether they’re being done by a foreign government, or our own.

与此同时,核心问题往往几乎无法回答。通威的廉价电力是否来自国有公用事业的政府补贴?海姆洛克的税收抵免保护其免受高电价的影响又如何?中国企业通常可以在工业园区获得廉价土地,这常常被视为一种补贴。但将美国土地划为工业用途是否也算作补贴?大多数国家都有研发税收抵免,并竞争降低企业税率以鼓励投资。决定这些举措是否被视为国家主义工业政策(不利)或营造商业友好环境(有利)的因素,通常是它们是由外国政府还是我们自己的政府实施。

What’s clear in retrospect, however, is that Asbeck’s claims had little solid basis. The telltale sign of a subsidized industry is that prices spring back up once competitors have been squeezed out and the government withdraws support — but the opposite has happened with solar panels, which now sell for roughly 5% of what they cost in 2011.

然而,回顾过去,很明显阿斯贝克的说法几乎没有坚实的基础。一个被补贴行业的明显特征是,一旦竞争对手被挤出市场,政府撤回支持,价格就会反弹——但太阳能电池板的情况正好相反,现在的售价大约是 2011 年成本的 5%。

At the World Trade Organization (WTO), which has a more rigorous definition of subsidy than US and European governments, there has only ever been a single case alleging subsidy against the Chinese solar industry — and that has been dormant since 2011. A separate WTO panel in 2014 found the US antidumping decision resulting from Asbeck’s complaint went against the trade body’s own rules.

在世界贸易组织(WTO)中,其对补贴的定义比美国和欧洲政府更为严格,针对中国太阳能产业的补贴指控仅有过一次——自 2011 年以来该案件一直处于休眠状态。2014 年,WTO 的一个独立小组发现,因 Asbeck 的投诉而作出的美国反倾销决定违反了该贸易组织的自身规则。

Still, one might have expected American solar-panel manufacturers to have responded with jubilation to Washington’s trade broadside against Beijing. In fact, the effect was much more like fear. The US in 2011 was making more money selling polysilicon and solar machinery to China than it was spending buying completed panels. That meant it was highly vulnerable to retaliation. In July 2012, two months after Washington found in favor of Asbeck, the counterattack began: China’s Ministry of Commerce announced an investigation into whether the US was dumping polysilicon into the mainland market.

尽管如此,人们可能会期望美国太阳能电池板制造商对华盛顿对北京的贸易攻击作出欢欣鼓舞的反应。事实上,效果更像是恐惧。2011 年,美国从向中国销售多晶硅和太阳能设备中赚取的利润超过了购买成品面板的支出。这意味着它对报复极为脆弱。2012 年 7 月,在华盛顿支持阿斯贝克的两个月后,反击开始了:中国商务部宣布对美国是否向大陆市场倾销多晶硅进行调查。

Chinese panel producers didn’t wait for their government’s ruling to act. With spot prices slumping well below the long-term contracts preferred by incumbent polysilicon producers, they canceled purchases en masse. By the end of the year, the decline in Hemlock’s sales into China had “reached dire levels,” Corning’s CFO Jim Flaws told a January 2013 earnings call. “The market for solar grade polysilicon is almost non-existent now.”

中国面板生产商并没有等待政府的裁决就采取了行动。由于现货价格大幅低于现有多晶硅生产商所偏好的长期合同,他们大规模取消了采购。到年底,Hemlock 对中国的销售下降已“达到了严重的水平”,康宁的首席财务官吉姆·弗劳斯在 2013 年 1 月的财报电话会议上表示。“太阳能级多晶硅的市场几乎不存在了。”

The European Union, where Asbeck had been at work bringing more antidumping cases, was in a similar situation, but officials there struck a compromise agreement in 2013 that helped the main local polysilicon producer, Wacker Chemie AG, maintain access to China. Despite concerted lobbying, the US failed to do the same. The result was a direct hit on Hemlock, with tariffs of 57% on American polysilicon imports.

欧洲联盟,Asbeck 在此工作以增加反倾销案件,也面临类似情况,但当地官员在 2013 年达成了一项妥协协议,帮助主要的本地多晶硅生产商 Wacker Chemie AG 维持对中国的准入。尽管进行了集中游说,美国未能做到这一点。结果直接打击了 Hemlock,对美国多晶硅进口征收 57%的关税。

That was just what China’s nascent polysilicon industry needed. “At that time, Chinese polysilicon producers were not cost competitive,” says Johannes Bernreuter, an analyst who’s studied the solar poly market since the early 2000s. “That gave them a protection wall to develop. It was no coincidence that six Chinese manufacturers returned from a dormant state to production in the course of 2013 when the antidumping duties were introduced.”

这正是中国新兴多晶硅产业所需要的。“在那个时候,中国的多晶硅生产商并没有成本竞争力,”分析师约翰内斯·伯恩鲁特(Johannes Bernreuter)说,他自 2000 年代初以来一直在研究太阳能多晶硅市场。“这为他们提供了一个保护壁垒来发展。2013 年反倾销税引入时,六家中国制造商从休眠状态恢复生产并非巧合。”

The opposite happened in the US. Taking fright, Mitsubishi sold out of the Hemlock venture in 2013. The following year, about six months after Beachy took over as Hemlock’s chairman, she had to announce the closure of the promised Tennessee plant. “It was pretty painful to be honest,” she recalls.

在美国则发生了相反的情况。三菱在 2013 年因恐慌而退出了 Hemlock 的投资。次年,大约在 Beachy 接任 Hemlock 董事长六个月后,她不得不宣布关闭承诺中的田纳西工厂。“说实话,这真的很痛苦,”她回忆道。

In Pasadena, Texas, a polysilicon factory owned by solar developer SunEdison Inc. was shuttered in 2016 when the company went bankrupt, blaming Beijing’s retaliatory tariffs. Its innovative technology was bought by GCL Technology Holdings Ltd., a Chinese rival.

在德克萨斯州的帕萨迪纳,太阳能开发商 SunEdison Inc.拥有的一家多晶硅工厂在 2016 年关闭,原因是该公司破产,指责北京的报复性关税。其创新技术被中国竞争对手 GCL 科技控股有限公司收购。

In Washington state, REC Silicon ASA shut its plant in Moses Lake in 2019, again citing the tariffs imposed by China. A second REC factory in Butte, Montana limped on until its closure was announced this February. Sustained by ongoing demand from its original customers in the chip industry, Hemlock kept going — but it quit making PV-grade polysilicon altogether in 2019 and 2020. At a time when the solar industry was scaling new heights, America’s manufacturing sector had quit the field.

在华盛顿州,REC Silicon ASA 于 2019 年关闭了位于摩西湖的工厂,再次提到中国施加的关税。位于蒙大拿州布特的第二家 REC 工厂一直勉强维持,直到今年二月宣布关闭。在芯片行业原有客户的持续需求支持下,Hemlock 继续运营——但它在 2019 年和 2020 年完全停止了光伏级多晶硅的生产。在太阳能行业达到新高度的同时,美国的制造业已退出这一领域。

Today, Tongwei has expanded beyond recognition.

今天,通威已经发展到令人难以置信的地步。

It now has facilities dotted across China’s renewables-rich outlying regions, where power is cheap: in Sichuan; in tropical, hydro-fueled Yunnan; and in Inner Mongolia, rich in sunshine and wind, as well as dirty coal. Even its Leshan operations have long outgrown their original site. The new plant sprawls over a vast campus downstream from the city. Silvery pipes carry chemicals to the distillation towers where silicon is purified, resembling a monumental church organ. A phalanx of pylons brings in electricity. A second Tongwei plant on a similar scale sits just across the road, while GCL Technology has a third hulking over a neighboring plot.

它现在在中国可再生能源丰富的边缘地区设有设施,这些地方电力便宜:在四川;在热带的水电丰富的云南;以及在阳光和风能丰富的内蒙古,还有脏煤。即使是乐山的运营也早已超出了其原始地点。新工厂占据了城市下游的一个广阔校园。银色的管道将化学品输送到精炼硅的蒸馏塔,形状类似于一座宏伟的教堂风琴。一排电塔输送电力。第二个同维工厂规模相似,位于马路对面,而 GCL 科技在邻近地块上还有一个庞大的工厂。

The site is sparkling. The roughly 2,000 people who work here mostly toil away from sight. They have dormitories, canteens, and an on-site gymnasium. A brand-new blue glass building on an artificial hill above a pond is a museum for visitors, illustrating the polysilicon production process and the history of the business. On the grass slope, beds of orange flowers have been pruned to spell out the Chinese characters for “lucid waters and lush mountains” — a quote from Xi Jinping seen as emblematic of the president’s support for the environment.

这个地方熠熠生辉。大约 2000 名在这里工作的人大多在视线之外辛勤工作。他们有宿舍、食堂和一个现场健身房。一个崭新的蓝色玻璃建筑坐落在一个人工山丘上,俯瞰着一个池塘,是一个供游客参观的博物馆,展示了多晶硅生产过程和公司的历史。在草坡上,橙色花朵的花坛被修剪成汉字“绿水青山”——这是习近平的一句名言,被视为总统对环境支持的象征。

Inside, a framed certificate confirms that the factory’s 2022 power supply was 100% renewable — a total of 2.38 gigawatt-hours, nearly enough to power Ireland for a month. Nearby, an illuminated panel displays a bar chart of the world’s polysilicon centers. On the far right of the chart sits a squat bar representing Hemlock, with a modest 30,000 metric tons a year. The Leshan site alone can produce about 120,000 tons, and Tongwei as a whole will have a capacity of 480,000 tons this year.

内部,一份框架证书确认该工厂 2022 年的电力供应为 100%可再生——总计 2.38 吉瓦时,几乎足够为爱尔兰提供一个月的电力。在附近,一个发光面板展示了全球多晶硅中心的柱状图。在图表的最右侧,有一根矮胖的柱子代表 Hemlock,年产量为 30,000 公吨。乐山工厂单独可以生产约 120,000 吨,而通威整体今年的产能将达到 480,000 吨。

Those numbers are astounding when you consider the amount of energy they represent: 480,000 tons is enough to generate sufficient solar electricity to power Mexico for a year — or Indonesia, or the UK and Ireland put together. Over their lifetime, those solar panels will provide nearly five times as much useful energy to the world economy as all the oil and gas in Exxon Mobil Corp.’s underground petroleum reserves.

这些数字令人震惊,考虑到它们所代表的能源量:48 万吨足以产生足够的太阳能电力,供墨西哥使用一年——或者印尼,或者英国和爱尔兰加在一起。在它们的使用寿命内,这些太阳能电池板将为全球经济提供近五倍于埃克森美孚公司地下石油储备中所有石油和天然气的有用能源。

Tongwei may be little-known outside China, but it’s by far the world’s biggest producer of polysilicon and should already be considered one of the most important energy companies globally. That dominance will only grow if plans announced in December to nearly double output go ahead.

通威在中国以外可能鲜为人知,但它是全球最大的多晶硅生产商,应该被视为全球最重要的能源公司之一。如果去年 12 月宣布的几乎将产量翻倍的计划得以实施,这一主导地位只会进一步增强。

Over a lunch of chicken-feet skewers, steamed fish, braised tofu, and orange juice in the factory’s office suite, the site’s strategic development director, Ding Xiaoke, speaking through a translator, describes a business strikingly different to the popular image of state-subsidized behemoths intent on undermining rivals in Europe and the US. The tariffs on Chinese solar products recently announced by Biden don’t concern him, because the plant doesn’t have any customers in the US. He’s interested in setting up production bases overseas but worried they won’t match Sichuan’s low costs.

在工厂办公室套房里,吃着鸡爪串、蒸鱼、红烧豆腐和橙汁,现场的战略发展总监丁晓可通过翻译描述了一家与公众对国家补贴巨头意图削弱欧洲和美国竞争对手的形象截然不同的企业。拜登最近宣布的对中国太阳能产品的关税并不让他担心,因为工厂在美国没有客户。他对在海外建立生产基地感兴趣,但担心这些基地无法与四川的低成本相匹配。

“For Tongwei, everything is about the market,” he said. Political issues such as trade barriers “might determine how fast we put investment in a specific region, but it won’t stop us growing.”

“对于通威来说,一切都与市场有关,”他说。贸易壁垒等政治问题“可能会决定我们在特定地区投资的速度,但不会阻止我们增长。”

Above all, he describes a business not only lacking state support, but largely left to its own devices by its corporate parent. (The Leshan facility is technically run by Sichuan Yongxiang Co., a subsidiary of the fish food-to-solar Tongwei Co. parent.) By Ding’s account, it’s as likely to compete as collaborate with Tongwei’s polysilicon facilities in other Chinese provinces.

最重要的是,他描述了一家不仅缺乏国家支持,而且在很大程度上被其母公司放任自流的企业。(乐山工厂在技术上由四川永翔公司运营,该公司是鱼饲料到太阳能的通威公司的子公司。)根据丁的说法,它与通威在其他中国省份的多晶硅设施竞争的可能性与合作的可能性一样大。

That image of pure independence isn’t 100% accurate. Tongwei Co.’s own accounts list a total of 2.19 billion yuan ($301 million) in government grants and tax concessions to the parent company since 2009, with more than half the total accrued last year as its capacity expansion went into overdrive. At the same time, the financials provide precious little evidence of the sort of comprehensive backing that’s usually assumed to explain the low cost of Chinese photovoltaic panels, especially when benchmarked against First Solar, the only US rival with comparable accounts that’s remained in operation throughout the past decade.

这种纯粹独立的形象并不完全准确。通威股份自 2009 年以来的账目中列出了总计 21.9 亿元人民币(3.01 亿美元)的政府补助和税收优惠,其中超过一半的总额是在去年随着其产能扩张的加速而累积的。同时,财务数据几乎没有提供通常被认为能够解释中国光伏面板低成本的全面支持的证据,尤其是与第一太阳能公司进行基准比较时,后者是唯一一家在过去十年中持续运营的具有可比账目的美国竞争对手。

Far from benefiting from cheap land, tax discounts and below-market loans, the Chinese company, if anything, is notable for how closely its business resembles its smaller US rival. The value of its land rights as a share of property, plant and equipment is about 4.9%, compared with a 0.8% share for the land on First Solar’s balance sheet. That suggests that — far from receiving benefits — Tongwei is spending more on land. Since the start of 2009, taxes on its income have amounted to about 30% of the pre-tax total; First Solar managed a dramatically lower 12.8%. Tongwei’s weighted average cost of capital — a proxy for any advantage it’s getting from low-cost loans — was 11.9%, almost identical to the 11.8% at First Solar.

远非受益于廉价土地、税收优惠和低于市场的贷款,这家中国公司如果有什么值得注意的,反而是其业务与其较小的美国竞争对手的相似程度。其土地使用权在物业、厂房和设备中的价值占比约为 4.9%,而第一太阳能的资产负债表上土地的占比仅为 0.8%。这表明——远非获得好处——通威在土地上的支出更高。自 2009 年初以来,其收入税额约占税前总额的 30%;而第一太阳能的税额则显著低至 12.8%。通威的加权平均资本成本——作为其从低成本贷款中获得的任何优势的代理——为 11.9%,几乎与第一太阳能的 11.8%相同。

As for subsidies, First Solar’s since 2009 have amounted to about three times the amount reported by Tongwei — $967 million in grants, tax credits, loan guarantees — according to a database compiled by corporate accountability lobby Good Jobs First. About 90% of the total was development and export financing for projects in Chile, Canada and India. (Thanks to its complex ownership structure, Hemlock Semiconductor doesn’t provide comparable financial data, although data from the company and the Good Jobs First database indicates $618 million in subsidies since 2008.)

关于补贴,自 2009 年以来,第一太阳能获得的补贴金额约为通威报告金额的三倍——9.67 亿美元的赠款、税收抵免和贷款担保——根据企业问责游说组织“良好工作优先”编制的数据库。总额的约 90%用于智利、加拿大和印度的项目开发和出口融资。(由于其复杂的所有权结构,Hemlock 半导体未提供可比的财务数据,尽管该公司和“良好工作优先”数据库的数据表明,自 2008 年以来获得了 6.18 亿美元的补贴。)

Tongwei’s factory is one of several enormous polysilicon plants south of Leshan.

通威的工厂是乐山南部几座巨型多晶硅工厂之一。

Photographer: David Fickling/Bloomberg

摄影师:大卫·菲克林/彭博社

The real support that Tongwei has received has been something far more indirect: the certainty of robust government backing for renewable power. Long after Germany and Spain canceled the subsidies that encouraged the renewables industry to grow so fast during the 2000s, China’s program was still active. It didn’t provide any direct support for manufacturers but ensured a level of demand from utilities that allowed solar factories to grow beyond their troubled infancy to their current profitable status. (The Chinese subsidy program was closed at the end of 2021.)

通威所获得的真正支持是更为间接的:对可再生能源的强有力政府支持的确定性。在德国和西班牙取消了鼓励可再生能源行业在 2000 年代快速增长的补贴后很久,中国的项目仍然在进行。它没有为制造商提供任何直接支持,但确保了来自公用事业的需求水平,使太阳能工厂能够从其困扰的初期成长到目前的盈利状态。(中国的补贴计划于 2021 年底关闭。)

By providing policy certainty and an investment-friendly environment — two things that businesses lobby for in every country on the planet — China has built a solar industry whose lead is by now likely to be unassailable. Polysilicon is the bedrock of the solar supply chain. If it can’t be produced at competitive prices, the domestic industry is at best going to be assembling photovoltaic products manufactured elsewhere. That’s now the only plausible path for the rest of the world, according to Bernreuter.

通过提供政策确定性和投资友好的环境——这是全球各国企业所游说的两件事——中国已经建立了一个太阳能产业,其领先地位现在可能是不可动摇的。多晶硅是太阳能供应链的基石。如果无法以具有竞争力的价格生产,多数国内产业充其量只能组装在其他地方制造的光伏产品。根据伯恩鲁特的说法,这现在是世界其他地区唯一合理的路径。

“I don’t think there will be a renaissance for the US, Europe and Japan. I cannot imagine that,” he says. “They cannot compete with the Chinese players any more.”

“我认为美国、欧洲和日本不会迎来复兴。我无法想象,”他说。“他们再也无法与中国企业竞争。”

If you want to imagine an alternative path for the global solar industry, you need only look to the history of Hemlock’s home state.

如果你想想象全球太阳能产业的另一条道路,只需看看 Hemlock 的家乡州的历史。

When Henry Ford was laying the foundations of the modern automotive industry in Detroit, one of his key innovations was building on a scale that shocked the competition into submission. His Highland Park plant was the largest factory the world had ever seen when it opened in 1910. The River Rouge facility, built less than a decade later, was nearly 10 times larger. It accommodated its own power plant, docks and steel mill, in an area greater than London’s entire financial district.

当亨利·福特在底特律奠定现代汽车工业的基础时,他的一个关键创新是以震惊竞争对手的规模进行生产。他的高地公园工厂在 1910 年开业时是世界上最大的工厂。不到十年后建成的河口设施几乎大了 10 倍。它拥有自己的发电厂、码头和钢铁厂,面积超过伦敦整个金融区。

The secret? Economies of scale. A small factory in a stable market is unlikely to reduce costs very much. However, when building to epic proportions in a market growing at heroic rates, relatively minor tweaks to the manufacturing process will compound over time to drive ever-shrinking prices. In the 1960s, Intel Corp. founder Gordon Moore predicted that the number of transistors on computer chips would double every two years, a prediction that has held true up to the present. The same process explains why the similar semiconductors manufactured into solar panels cost about 4% now of what they did in 2009. China’s excellence in such cheap, large-scale manufacturing has turned it into the production base for 95% of the world’s iPhones. It’s hardly surprising that the same expertise has given it a lead in the solar industry, too.

秘密是什么?规模经济。一个在稳定市场中的小工厂不太可能大幅降低成本。然而,在一个以英雄速度增长的市场中,建造巨型工厂时,制造过程中的相对小调整会随着时间的推移而累积,推动价格不断下降。在 1960 年代,英特尔公司创始人戈登·摩尔预测,计算机芯片上的晶体管数量每两年将翻一番,这一预测至今仍然成立。同样的过程也解释了为什么制造太阳能电池板的类似半导体现在的成本仅为 2009 年的约 4%。中国在这种廉价、大规模制造方面的卓越表现使其成为全球 95% iPhone 的生产基地。毫不奇怪的是,这种专业知识也使其在太阳能行业中处于领先地位。

For that process to work, however, manufacturers have to be convinced that their bold investments will pay off — either because they’re more efficient than their rivals, or because they’re confident that long-term demand will be unstoppable.

然而,为了使这一过程有效,制造商必须确信他们的大胆投资会获得回报——要么是因为他们比竞争对手更高效,要么是因为他们相信长期需求将不可阻挡。

Businesses and nations commit aggressively to the projects that they think present opportunities for them. China’s support for solar developers is so unwavering, in part, because — unlike the US (which is currently pumping more oil and gas than any nation in history) — it’s desperately short of domestic energy sources, other than coal reserves whose costs are ever-rising and whose fumes threaten to choke its cities.

企业和国家积极承诺他们认为对自己有机会的项目。中国对太阳能开发商的支持如此坚定,部分原因在于——与美国(目前正在开采历史上任何国家都未曾达到的石油和天然气)不同——中国在国内能源来源上极度短缺,除了煤炭储备,其成本不断上升,烟雾威胁着城市的生存。

The amount of coal, petroleum or hydroelectric power that a country can produce is an ineluctable fact of its geography, so China’s ability to transform such energy into economic growth is heavily dependent on imports from other countries. That’s a concern for Beijing — but solar and wind power are different. The key to their development isn’t geological happenstance but manufacturing prowess, one field in which China has few peers.

一个国家能够生产的煤炭、石油或水电的数量是其地理位置的不可避免的事实,因此中国将这些能源转化为经济增长的能力在很大程度上依赖于从其他国家的进口。这让北京感到担忧——但太阳能和风能则不同。它们发展的关键不是地质偶然,而是制造能力,而这是中国在这一领域几乎没有对手。

An economist would tell you that the ideal way to structure global trade is for countries to specialize in the products where they have the greatest comparative advantage. If China can produce cheaper solar panels than anyone else, then other nations should buy them and send back in return whatever they can produce at record-low prices. The corn and soybean fields that surround the Hemlock polysilicon plant are a case in point. Last year, US exports of the two crops amounted to $28 billion and $13.7 billion respectively, a total greater than the $22 billion it spent on imported solar panels.

一位经济学家会告诉你,理想的全球贸易结构是各国专注于它们具有最大比较优势的产品。如果中国能以比其他国家更低的价格生产太阳能电池板,那么其他国家应该购买这些电池板,并以它们能以创纪录低价生产的任何产品作为回报。环绕 Hemlock 多晶硅工厂的玉米和大豆田就是一个例子。去年,美国这两种作物的出口额分别为 280 亿美元和 137 亿美元,总额超过了其在进口太阳能电池板上花费的 220 亿美元。

The Covid-19 pandemic made that view look impossibly unfashionable, as it triggered a worldwide rethinking of supply chains. Alarm in the US and EU grew further when Russia weaponized its gas exports amid the invasion of Ukraine. If authoritarian powers have too much control over a source of energy, they might be able to bend even democracies to their will.

新冠疫情使这种观点显得极为不合时宜,因为它引发了全球对供应链的重新思考。当俄罗斯在入侵乌克兰期间将其天然气出口武器化时,美国和欧盟的警觉进一步加剧。如果专制国家对某种能源的控制过于强大,它们可能会使即使是民主国家也屈从于其意志。

That analogy, however, doesn’t really make any sense in the case of solar. Russia’s gas companies sell fuel, but China’s solar businesses sell machines for producing energy from daylight. The distinction is crucial: Moscow can turn off Europe’s gas taps, but Beijing can’t turn off the sun. Even so, the mere fact of China’s dominance, largely shrugged off in 2019, has assumed the significance of a global emergency in 2024.

然而,这种类比在太阳能的情况下并没有真正的意义。俄罗斯的天然气公司出售燃料,但中国的太阳能企业出售用于从阳光中生产能源的机器。这一区别至关重要:莫斯科可以关闭欧洲的天然气阀门,但北京无法关闭太阳。即便如此,中国的主导地位在 2019 年时大多被忽视,但在 2024 年已成为全球紧急情况的重要标志。

The trouble is, it’s too late now to wind back the knock-on effects. If US and European subsidies to solar hadn’t been cut because of the bad political smell from Solyndra and the wave of austerity that followed the 2008 financial crisis, then local renewable developers would have been more active and manufacturers would have seen more demand for their products. If a charismatic German hadn’t bounced the US into an accidental tariff war with China in the early 2010s, those proposed American polysilicon plants might have been built. The process innovation that’s happened over the past decade in Leshan might have occurred in Hemlock, Clarksville, Moses Lake and Pasadena instead.

问题是,现在已经太晚了,无法扭转连锁反应。如果美国和欧洲对太阳能的补贴没有因为 Solyndra 的政治丑闻和 2008 年金融危机后随之而来的紧缩政策而被削减,那么当地的可再生能源开发商会更加活跃,制造商也会看到他们产品的需求增加。如果一位有魅力的德国人没有在 2010 年代初期将美国拖入与中国的意外关税战争,那些提议中的美国多晶硅工厂可能会建成。在过去十年中在乐山发生的过程创新本可以在 Hemlock、Clarksville、Moses Lake 和 Pasadena 发生。

Installers see no reason to prefer local products. “Over the last year or so we have not seen a huge disparity between Chinese- and American-made,” says Randy French, founder of Independent Solar, a company that’s been installing residential systems for 21 years in California, Arizona, Nevada and Texas. “They’re all really great products right now,” he says. “Chinese or anything.”

安装商没有理由偏好本地产品。“在过去一年左右的时间里,我们没有看到中国产品和美国产品之间存在巨大差异,”独立太阳能公司的创始人兰迪·法伦说,该公司在加利福尼亚、亚利桑那、内华达和德克萨斯州安装住宅系统已有 21 年。“现在它们都是非常好的产品,”他说。“无论是中国的还是其他的。”

The US solar industry that’s left is moribund at best. SunPower Corp., a once-venerable name in the US solar industry which was worth at much as $12.5 billion at its peak in 2007, filed for bankruptcy in August. Three weeks later, Switzerland’s Meyer Burger Technology AG canceled plans to build a 2 GW solar cell plant in Colorado, saying the site was no longer financially viable and it would manufacture in Germany instead.

美国的太阳能行业现状堪忧。曾经在 2007 年市值高达 125 亿美元的美国太阳能行业知名企业 SunPower Corp.于 8 月申请破产。三周后,瑞士的 Meyer Burger Technology AG 取消了在科罗拉多州建设 2 GW 太阳能电池厂的计划,称该地点已不再具有财务可行性,计划改为在德国生产。

The following week, Maxeon Solar Technologies Ltd., SunPower’s manufacturing arm before a 2019 spin-off, dropped its earnings guidance, after customs checks at the Mexican border halted imports to the US, its largest market. Start-up CubicPV Inc. in February announced it was abandoning plans to build a US plant capable of slicing polysilicon into enough thin wafers to make 10 gigawatts per year of panels.

下周,Maxeon Solar Technologies Ltd.(在 2019 年分拆前是 SunPower 的制造部门)下调了其盈利指引,因为墨西哥边境的海关检查暂停了对美国的进口,而美国是其最大市场。初创公司 CubicPV Inc.在 2 月份宣布放弃在美国建造一座能够将多晶硅切割成足够薄的晶圆以生产每年 10 吉瓦面板的工厂的计划。

There are winners, to be sure, but not on a scale to meet the coming demand. First Solar, well-protected by tariffs, has seen its shares gain by about a quarter since the Biden administration’s latest round of levies in May.

确实有赢家,但规模不足以满足即将到来的需求。第一太阳能公司在关税的保护下,自拜登政府在五月实施最新一轮关税以来,其股价上涨了约四分之一。

South Korea’s Hanwha Solutions Corp., which produces panels under the Qcells brand, has also done well. Democratic presidential nominee Kamala Harris visited its plant in Dalton, Georgia last year and joked of her “maybe unique passion for solar energy”. In August, Qcells received a $1.45 billion government loan guarantee for a nearby factory that will produce 3.3 GW of wafers annually. That’s roughly one-tenth of the solar panels the US installed last year, and about one-twentieth of what will be needed annually if the country is to meet Biden’s promise to decarbonize America’s grid by 2035.

韩国汉华解决方案公司(Hanwha Solutions Corp.)旗下的 Qcells 品牌面板表现良好。民主党总统候选人卡马拉·哈里斯(Kamala Harris)去年访问了位于乔治亚州达尔顿的工厂,并开玩笑说她对太阳能的“或许独特的热情”。在八月份,Qcells 获得了 14.5 亿美元的政府贷款担保,用于附近一座将每年生产 3.3 吉瓦(GW)晶圆的工厂。这大约是美国去年安装的太阳能面板的十分之一,如果美国要实现拜登(Biden)在 2035 年前使电网脱碳的承诺,每年大约需要的数量是其二十分之一。

In Hemlock, too, activity is picking up. A US law passed in 2022 banned the import of products produced in China’s Xinjiang region unless there’s clear evidence that there was no forced labor in their supply chain. In theory, that shouldn’t be an insurmountable issue for Tongwei, which doesn’t operate in Xinjiang and appears to be “the safest bet in the Chinese polysilicon market,” according to a 2021 study by researchers at Sheffield Hallam University. In practice, however, the ban has acted as a de facto block on all polysilicon produced in China.

在 Hemlock,活动也在增加。2022 年通过的一项美国法律禁止进口在中国新疆地区生产的产品,除非有明确证据表明其供应链中没有强迫劳动。理论上,这对通威来说不应该是一个不可逾越的问题,因为通威并不在新疆运营,并且根据谢菲尔德哈勒姆大学 2021 年的一项研究,通威似乎是“中国多晶硅市场中最安全的选择”。然而,实际上,这项禁令实际上对中国生产的所有多晶硅形成了事实上的封锁。

In cornfields next to its existing plant, Hemlock is building a new polysilicon facility.

在其现有工厂旁边的玉米田中,Hemlock 正在建设一座新的多晶硅设施。

Photographer: David Fickling/Bloomberg

摄影师:大卫·菲克林/彭博社

That law inspired Hemlock Semiconductor to restart sales and production for the solar industry in 2021. Just to the west of the existing plant, work has already begun on a $375 million expansion. Residential plots have roughly doubled in price from $7,000 per acre to as much as $15,000 in anticipation of the influx of workers, according to Abbey Miller, a part-time real estate agent and server at a local diner.

该法律激励了 Hemlock Semiconductor 在 2021 年重新启动太阳能行业的销售和生产。在现有工厂的西侧,已经开始进行一项价值 3.75 亿美元的扩建。根据兼职房地产经纪人和当地餐馆服务员 Abbey Miller 的说法,住宅地块的价格大约翻了一番,从每英亩 7,000 美元上涨到高达 15,000 美元,以期待工人涌入。

“The U.S. solar industry is at an important inflection point and the market is demanding U.S.-made polysilicon because of its high quality and traceability,” a spokeswoman for Hemlock said in an e-mailed statement. “The momentum in the market will only accelerate the build out of a domestic supply chain and help us explore opportunities to expand capacity to keep pace with growing demand.”

“美国太阳能行业正处于一个重要的转折点,市场对美国制造的多晶硅的需求正在增加,因为其高质量和可追溯性,”Hemlock 的一位发言人在一份电子邮件声明中表示。“市场的势头将进一步加速国内供应链的建设,并帮助我们探索扩大产能的机会,以跟上不断增长的需求。”

It’s not clear how much of Hemlock’s new production will go to the solar industry, and how much to semiconductors — but if you were making a bet, you still wouldn’t put it on PV. What the US really cares about is the ultra-pure polysilicon for microchips that’s central to America’s desire to make computing power — not solar power — a key national security advantage against China. The CHIPS Act, signed by Biden in 2022, provides around $52 billion in subsidies to the US microprocessor industry, sums beyond the imagination of what the solar sector has enjoyed anywhere. The Loan Programs Office, a government agency with authority to issue hundreds of billions in loans to promising energy projects and headed up by former solar entrepreneur Jigar Shah, didn’t lend money to a PV manufacturer between the collapse of Solyndra in 2011 and August’s loan to Qcells.

目前尚不清楚 Hemlock 的新生产中有多少会用于太阳能行业,多少会用于半导体——但如果你要下注,仍然不会选择光伏。美国真正关心的是用于微芯片的超纯多晶硅,这对美国希望将计算能力——而非太阳能——作为对中国的关键国家安全优势至关重要。拜登在 2022 年签署的《芯片法案》为美国微处理器行业提供了约 520 亿美元的补贴,这一数字超出了太阳能行业所享受的任何想象。贷款项目办公室是一个有权向有前景的能源项目发放数千亿美元贷款的政府机构,由前太阳能企业家 Jigar Shah 领导,在 2011 年 Solyndra 倒闭与 8 月份对 Qcells 的贷款之间,没有向任何光伏制造商提供资金。

The purported rationale of US tariffs on imported solar is one founding father Alexander Hamilton would have recognized: to protect a fledgling industry until it is strong enough to stand on its own feet. No one I have spoken to in the solar industry, however, sees that happening. To have a functioning PV sector you need every piece of the supply chain — from polysilicon, ingot production and wafer slicing to cell manufacturing and finally module assembly. There’s precious little sign that’s going to emerge on a sufficient scale in the US, not least because China’s production efficiencies are so much greater.

美国对进口太阳能征收关税的所谓理由是创始人亚历山大·汉密尔顿会认同的:保护一个初创行业,直到它足够强大,能够独立生存。然而,我与太阳能行业的每一个人交谈后,都没有人认为这会发生。要拥有一个正常运作的光伏行业,你需要供应链的每一个环节——从多晶硅、锭生产和晶圆切割到电池制造,最后到组件组装。美国几乎没有迹象表明这些环节会在足够规模上出现,尤其是因为中国的生产效率要高得多。

Successive waves of tariffs have done little more than create a Potemkin solar industry, while putting a tax on clean power as the climate crisis festers. The US installed about half as many solar panels in 2023 as the European Union, despite a far richer natural endowment of clear skies and bright sunlight.

连续的关税浪潮几乎没有做更多的事情,只是创造了一个虚假的太阳能产业,同时在气候危机加剧的情况下对清洁能源征税。尽管美国拥有更丰富的自然条件,包括晴朗的天空和明亮的阳光,但 2023 年安装的太阳能电池板数量仅为欧盟的一半。

If America wants a sort of small-batch, artisan solar sector to give the impression it’s doing the work of staving off climate change, while going all-in on expanding petroleum production instead, then it’s hit on the right policy. US manufacturers can survive in the walled garden of the domestic market, but the protectionism that sustains them means they’ll never grow efficient and cheap enough to survive the savage competition of the global market. That’s where Chinese companies reign supreme. “China really wanted the solar industry,” says Hemlock’s former president, Beachy. “We gave that away as a country.”

如果美国想要一个小规模、手工艺的太阳能行业,以给人一种正在努力抵御气候变化的印象,同时却全力扩展石油生产,那么它就找到了正确的政策。美国制造商可以在国内市场的围墙花园中生存,但支撑他们的保护主义意味着他们永远无法变得足够高效和便宜,以在全球市场的激烈竞争中生存。这正是中国公司称霸的地方。“中国真的想要太阳能产业,”海姆洛克的前总裁比奇说。“我们作为一个国家把这个机会让了出去。”

It’s a tragic failure of vision and ambition. In Detroit a century ago, US automobile entrepreneurs created an industry that irrevocably transformed cities, countries and economies. This time around, China’s innovators are the ones changing the world.

这是对愿景和雄心的悲惨失败。一个世纪前,在底特律,美国汽车企业家创造了一个行业,彻底改变了城市、国家和经济。这一次,中国的创新者正在改变世界。