Abstract 抽象的

Enhancing the intracellular labile iron pool (LIP) represents a powerful, yet untapped strategy for driving ferroptotic death of cancer cells. Here, we show that NRF2 maintains iron homeostasis by controlling HERC2 (E3 ubiquitin ligase for NCOA4 and FBXL5) and VAMP8 (mediates autophagosome-lysosome fusion). NFE2L2/NRF2 knockout cells have low HERC2 expression, leading to a simultaneous increase in ferritin and NCOA4 and recruitment of apoferritin into the autophagosome. NFE2L2/NRF2 knockout cells also have low VAMP8 expression, which leads to ferritinophagy blockage. Therefore, deletion of NFE2L2/NRF2 results in apoferritin accumulation in the autophagosome, an elevated LIP, and enhanced sensitivity to ferroptosis. Concordantly, NRF2 levels correlate with HERC2 and VAMP8 in human ovarian cancer tissues, as well as ferroptosis resistance in a panel of ovarian cancer cell lines. Last, the feasibility of inhibiting NRF2 to increase the LIP and kill cancer cells via ferroptosis was demonstrated in preclinical models, signifying the impact of NRF2 inhibition in cancer treatment.

增强细胞内不稳定铁池(LIP)是驱动癌细胞铁死亡的一种强大但尚未开发的策略。在这里,我们表明 NRF2 通过控制 HERC2(NCOA4 和 FBXL5 的 E3 泛素连接酶)和 VAMP8(介导自噬体-溶酶体融合)来维持铁稳态。 NFE2L2/NRF2敲除细胞的HERC2表达较低,导致铁蛋白和 NCOA4 同时增加,并将脱铁铁蛋白募集到自噬体中。 NFE2L2/NRF2敲除细胞的VAMP8表达也较低,这会导致铁蛋白自噬受阻。因此, NFE2L2/NRF2的缺失会导致自噬体中脱铁铁蛋白的积累、LIP 升高以及对铁死亡的敏感性增强。一致地,NRF2 水平与人类卵巢癌组织中的 HERC2 和 VAMP8 以及一组卵巢癌细胞系中的铁死亡抗性相关。最后,在临床前模型中证明了抑制NRF2以增加LIP并通过铁死亡杀死癌细胞的可行性,这表明了NRF2抑制在癌症治疗中的影响。

NRF2 regulates ferritin synthesis and degradation to maintain iron homeostasis and prevent ferroptotic cell death.

NRF2 调节铁蛋白的合成和降解,以维持铁稳态并防止铁死亡。

INTRODUCTION 介绍

The transcription factor nuclear factor erythroid 2–related factor 2 (NFE2L2/NRF2) was originally identified as a master regulator of cellular redox homeostasis and xenobiotic detoxification (1–3). Since then, NRF2 has been shown to regulate genes that are important for proteostasis, the pentose phosphate pathway, and the metabolism of amino acids and carbohydrates (4–9). In normal tissues, NRF2 protein levels are kept low through interaction with KEAP1 (an adaptor for an E3 ubiquitin ligase complex) that targets NRF2 for ubiquitylation and subsequent proteasomal degradation (10–13). Controlled activation of NRF2 in normal cells prevents cancer initiation induced by chemical carcinogens (14). However, recent evidence reveals that an oncogenic activity of NRF2, i.e., high NFE2L2/NRF2 expression, largely due to somatic mutation of Kelch-like ECH-associated protein 1 (KEAP1), promotes tumor progression, metastasis, and resistance to anticancer therapies (15–19). Clinically, high expression of NRF2 in patient tumors strongly correlates with a poor prognosis (20). Therefore, it is important to understand molecular mechanisms by which NRF2 helps cancer cells evade cell death to facilitate the development of innovative therapeutic strategies for effective treatment of cancer.

转录因子核因子红细胞 2 相关因子 2 ( NFE2L2 /NRF2) 最初被确定为细胞氧化还原稳态和异生物质解毒的主要调节因子。 1 – 3 )。从那时起,NRF2 已被证明可以调节对蛋白质稳态、磷酸戊糖途径以及氨基酸和碳水化合物代谢很重要的基因。 4 – 9 )。在正常组织中,NRF2 蛋白水平通过与 KEAP1(E3 泛素连接酶复合物的接头)相互作用而保持较低水平,KEAP1 靶向 NRF2 进行泛素化和随后的蛋白酶体降解。 10 – 13 )。正常细胞中 NRF2 的受控激活可防止化学致癌物诱导的癌症发生。 14 )。然而,最近的证据表明,NRF2 的致癌活性,即NFE2L2/NRF2高表达,主要是由于 Kelch 样 ECH 相关蛋白 1 ( KEAP1 ) 的体细胞突变,促进肿瘤进展、转移和抗癌治疗耐药性。 15 – 19 )。临床上,患者肿瘤中NRF2的高表达与不良预后密切相关。 20 )。因此,了解 NRF2 帮助癌细胞逃避细胞死亡的分子机制,以促进开发有效治疗癌症的创新治疗策略非常重要。

One hurdle in cancer treatment is acquired resistance, when the cancer cells are gradually desensitized to pro-apoptotic signals. In the hopes of discovering compounds to treat apoptosis-resistant Ras mutant cancer cells, a form of cell death termed ferroptosis was discovered (21, 22). Ferroptosis is an iron- and lipid peroxidation–driven form of cell death that is morphologically distinct from necrosis, apoptosis, and autophagy (22–25). The compounds discovered in this screen to induce ferroptosis, erastin, and RSL-3 were later found to inhibit the system xc-cystine/glutamate antiporter and key lipid peroxide reducing enzyme glutathione (GSH) peroxidase 4 (GPX4), respectively (26, 27). Over the past decade, many ferroptosis inducers [erastin, RSL-3, sorafenib, FIN-56, and sulfasalazine (SAS)] have been used to kill different cancer cell types in vitro (23). Imidazole ketone erastin (IKE), a modified form of erastin, was recently developed for in vivo use and shown to be pharmacologically stable, safe, and efficacious in the different murine cancer models tested (28, 29). Therefore, IKE has the potential to be used clinically to treat patients with aggressive, resistant, and metastatic cancer through ferroptotic cell death (30).

癌症治疗的障碍之一是获得性耐药,即癌细胞对促凋亡信号逐渐不敏感。为了找到治疗抗凋亡 Ras 突变癌细胞的化合物,发现了一种称为铁死亡的细胞死亡形式。 21 , 22 )。铁死亡是一种由铁和脂质过氧化驱动的细胞死亡形式,其形态与坏死、细胞凋亡和自噬不同。 22 – 25 )。在此筛选中发现的可诱导铁死亡的化合物、erastin 和 RSL-3 随后被发现分别抑制 xc-胱氨酸/谷氨酸逆向转运蛋白系统和关键的脂质过氧化物还原酶谷胱甘肽 (GSH) 过氧化物酶 4 (GPX4)。 26 , 27 )。在过去的十年中,许多铁死亡诱导剂 [erastin、RSL-3、索拉非尼、FIN-56 和柳氮磺吡啶 (SAS)] 已被用于在体外杀死不同类型的癌细胞。 23 )。咪唑酮erastin(IKE)是erastin的一种改良形式,最近被开发用于体内使用,并在不同的小鼠癌症模型测试中显示出药理学稳定、安全和有效的效果。 28 , 29 )。因此,IKE有潜力在临床上用于通过铁死亡细胞治疗侵袭性、耐药性和转移性癌症患者。 30 )。

Ferroptosis is an oxidative form of cell death that is triggered when there is excessive lipid peroxidation. Many critical ferroptosis proteins identified, such as solute carrier family 7 member 11 (SLC7A11; a subunit of the cystine/glutamate antiporter xCT) and the catalytic and modifier subunits of glutamate cysteine ligase (GCLC/GCLM), both of which control the level of GSH (a cofactor for GPX4), are well-defined NRF2 target genes (23, 31). Hence, the anti-ferroptotic activity of NRF2 was naturally thought to be derived from its antioxidant target genes (23). However, another essential aspect of ferroptosis is the labile iron pool (LIP), as iron chelation abolishes ferroptotic cell death in cells treated with a ferroptosis inducer (22, 23). Although an increasing number of pro-ferroptotic factors that control lipid peroxidation have been revealed (32–34), information regarding dysregulation of iron homeostasis during ferroptotic cell death is limited. The current study was designed to dissect the detailed molecular mechanisms by which NRF2 protects cancer cells against ferroptotic cell death via mitigation of both lipid peroxidation and free iron. Our results demonstrate that NRF2 controls ferritin synthesis and degradation through HECT and RLD domain containing E3 ubiquitin protein ligase 2 (HERC2), vesicle-associated membrane protein 8 (VAMP8), and nuclear receptor coactivator 4 (NCOA4), thus altering the intracellular LIP and dictating cancer cell susceptibility to ferroptotic cell death. Furthermore, the importance of this role of NRF2 in controlling iron homeostasis to dictate ferroptosis was demonstrated by the fact that HERC2/VAMP8 double knockout (KO) cells behaved equivalently to NFE2L2/NRF2 KO cells. Also, NCOA4 KO in NFE2L2/NRF2 KO cells protected against ferroptotic cell death. These results clearly validate the antioxidant-independent function of NRF2 in mediating the ferroptotic response. We also demonstrated that cancer cells with high NRF2 levels were more resistant to ferroptosis and that NRF2 inhibition sensitized these cancer cells to ferroptosis inducers. Last, using preclinical models, we provide solid evidence that ovarian tumor spheroids, xenografts, and patient-derived tumors can be sensitized to ferroptotic cell death by enhancing toxic free iron accumulation through NRF2 inhibition. Collectively, this study not only offers basic knowledge regarding how NRF2 controls iron homeostasis but also indicates the translational value of inhibiting NRF2 to enhance the LIP and drive cancer cell death through ferroptosis.

铁死亡是细胞死亡的一种氧化形式,当脂质过氧化过度时会触发。鉴定出许多关键的铁死亡蛋白,例如溶质载体家族 7 成员 11( SLC7A11 ;胱氨酸/谷氨酸逆向转运蛋白 xCT 的亚基)以及谷氨酸半胱氨酸连接酶( GCLC/GCLM )的催化和修饰亚基,两者都控制铁死亡的水平GSH(GPX4 的辅助因子)是明确定义的 NRF2 靶基因( 23 , 31 )。因此,NRF2的抗铁死亡活性自然被认为源自其抗氧化靶基因( 23 )。然而,铁死亡的另一个重要方面是不稳定铁池(LIP),因为铁螯合可以消除用铁死亡诱导剂处理的细胞中的铁死亡。 22 , 23 )。尽管已经发现越来越多的控制脂质过氧化的促铁死亡因子( 32 – 34 ),有关铁死亡细胞死亡过程中铁稳态失调的信息是有限的。目前的研究旨在剖析 NRF2 通过减轻脂质过氧化和游离铁来保护癌细胞免于铁死亡的详细分子机制。我们的结果表明,NRF2 通过含有 E3 泛素蛋白连接酶 2 (HERC2)、囊泡相关膜蛋白 8 (VAMP8) 和核受体辅激活因子 4 (NCOA4) 的 HECT 和 RLD 结构域控制铁蛋白合成和降解,从而改变细胞内 LIP 和决定癌细胞对铁死亡细胞的易感性。 此外, HERC2 / VAMP8双敲除 (KO) 细胞的行为与NFE2L2/NRF2 KO 细胞相当,这一事实证明了 NRF2 在控制铁稳态以指示铁死亡方面的重要性。此外, NFE2L2/NRF2 KO 细胞中的NCOA4 KO 可防止铁死亡细胞死亡。这些结果清楚地验证了 NRF2 在介导铁死亡反应中的独立于抗氧化剂的功能。我们还证明,具有高 NRF2 水平的癌细胞对铁死亡更具抵抗力,并且 NRF2 抑制使这些癌细胞对铁死亡诱导剂敏感。最后,利用临床前模型,我们提供了确凿的证据,证明卵巢肿瘤球体、异种移植物和患者来源的肿瘤可以通过抑制 NRF2 增强有毒游离铁的积累,从而对铁死亡细胞敏感。总的来说,这项研究不仅提供了有关 NRF2 如何控制铁稳态的基础知识,还表明了抑制 NRF2 增强 LIP 并通过铁死亡驱动癌细胞死亡的转化价值。

RESULTS 结果

NFE2L2/NRF2 deletion sensitizes ovarian cancer cells to ferroptosis

NFE2L2/NRF2缺失使卵巢癌细胞对铁死亡敏感

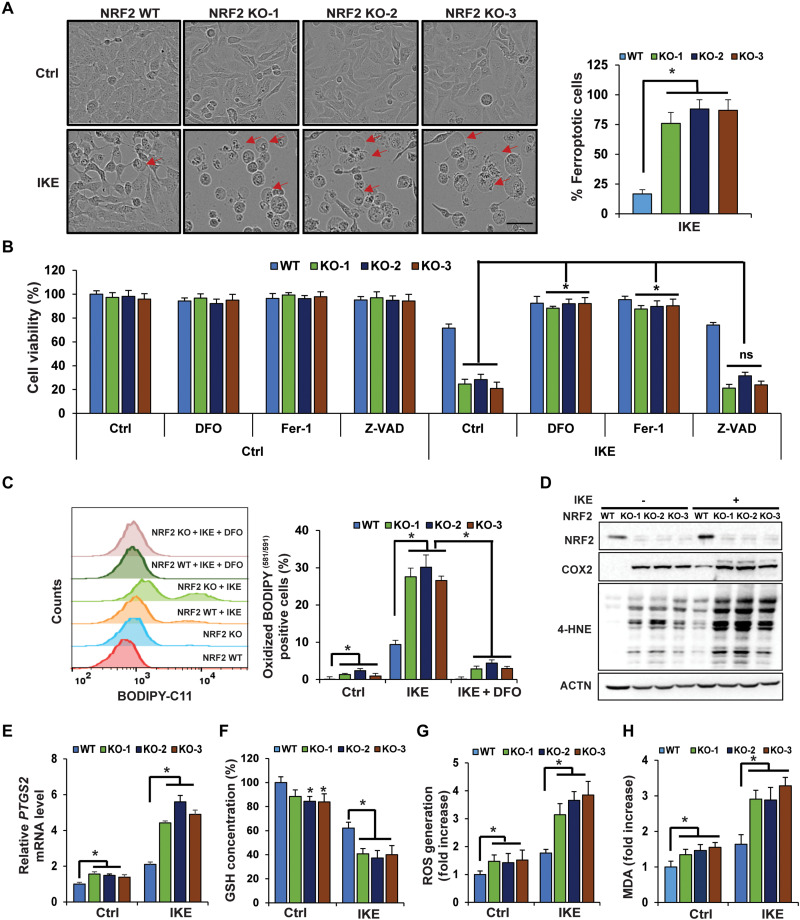

One of the many cancers that have been shown to have high levels of NRF2 is epithelial ovarian cancer, the most lethal gynecological cancer due to its aggressiveness, propensity to develop drug resistance, recurrence, and metastatic potential. Although more than 80% of ovarian cancer patients respond to first-line chemotherapy, the majority will develop recurrent tumors that are drug resistant and fatal. Treatment relapses of ovarian cancer patients continue to represent a major obstacle for its clinical management (35, 36). To determine the role of NRF2 in mediating ovarian cancer cell resistance to ferroptosis, CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing was used to establish NFE2L2/NRF2 KO SKOV-3 ovarian carcinoma cells, and three different NFE2L2/NRF2 KO clones, which were established using two different single-guide RNAs (sgRNAs), were chosen for further study. Successful deletion of NFE2L2/NRF2 was confirmed, with NRF2 protein levels being undetectable in all three KO cell lines, as well as lower mRNA and protein levels of several NRF2 target genes (fig. S1, A and B). Compared to wild type (WT), NFE2L2/NRF2 KO cells treated with IKE, a ferroptosis inducer that inhibits system xc-, exhibited a notable increase in the number of cells undergoing the “ballooning” morphology indicative of ferroptotic cell death (representative images of 24-hour treatment are presented in Fig. 1A: left panel shows ferroptotic cell morphology; right panel is the percentage of ferroptotic cells). IKE induced 18.66% ferroptotic cells in NFE2L2/NRF2 WT cells versus 76% in NFE2L2/NRF2 KO cells (Table 1). Consistent with the pro-ferroptotic change in morphology (Fig. 1A), IKE treatment resulted in an ~30% decrease in cell viability in NFE2L2/NRF2 WT, as compared to an ~75% decrease in NFE2L2/NRF2 KO cells at 24 hours, as measured by 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay (Fig. 1B). Furthermore, IKE-induced ferroptotic cell death was completely abolished by deferoxamine (DFO; an iron chelator), ferrostatin 1 (Fer-1; an inhibitor of lipid peroxidation), but not Z-VAD-fmk (a pan-caspase inhibitor) (Fig. 1B), indicating the importance of free iron accumulation and lipid peroxidation in promoting ferroptosis. Consistent with a ferroptosis-dependent decrease in cell viability, higher levels of lipid peroxides were also observed in IKE-treated NFE2L2/NRF2 KO cells, which could be reversed when the cells were cotreated with DFO (Fig. 1C). Next, more ferroptotic cell death in IKE-treated NFE2L2/NRF2 KO cells compared to NFE2L2/NRF2 WT cells was further confirmed via assessment of key ferroptosis markers, including higher mRNA levels of prostaglandin endoperoxide synthase 2 (PTGS2) and its protein product cyclooxygenase 2 (COX2) (Fig. 1, D and E), as well as increased 4-hydroxynonenal (4-HNE) protein adduct formation (Fig. 1D). In addition, NFE2L2/NRF2 KO cells had decreased total GSH levels, higher levels of reactive oxygen species (ROS), and more malondialdehyde (MDA) formation under untreated conditions (Fig. 1, F to H); IKE treatment further exacerbated the differences in these measurements between NFE2L2/NRF2 WT and KO cells (Fig. 1, F to H). Similar results were obtained when a less specific ferroptosis inducer, SAS, was used (fig. S1, C to J).

上皮性卵巢癌是众多具有高水平 NRF2 的癌症之一,由于其侵袭性、产生耐药性、复发和转移潜力,它是最致命的妇科癌症。尽管超过 80% 的卵巢癌患者对一线化疗有反应,但大多数患者会出现耐药且致命的复发性肿瘤。卵巢癌患者的治疗复发仍然是其临床管理的主要障碍。 35 , 36 )。为了确定NRF2在介导卵巢癌细胞对铁死亡的抵抗中的作用,使用CRISPR-Cas9基因编辑建立了NFE2L2/NRF2 KO SKOV-3卵巢癌细胞,以及使用两种不同的NFE2L2/NRF2 KO克隆建立了三个不同的NFE2L2/NRF2 KO克隆。选择单向导RNA(sgRNA)进行进一步研究。证实NFE2L2/NRF2成功删除,所有三种 KO 细胞系中均检测不到 NRF2 蛋白水平,并且多个 NRF2 靶基因的 mRNA 和蛋白水平较低(图 S1、A 和 B)。与野生型(WT)相比,用 IKE(一种抑制系统 xc- 的铁死亡诱导剂)处理的NFE2L2/NRF2 KO 细胞表现出经历“气球”形态的细胞数量显着增加,表明铁死亡细胞的数量(代表性图像24小时治疗介绍于 Fig. 1A :左图显示铁死亡细胞形态;右图是铁死亡细胞的百分比)。 IKE 在NFE2L2/NRF2 WT 细胞中诱导 18.66% 的铁死亡细胞,而在NFE2L2/NRF2 KO 细胞中诱导 76%( Table 1 )。 与形态上的促铁死亡变化一致( Fig. 1A ),通过3- (4,5-二甲基噻唑- 2-基)-2,5-二苯基溴化四唑(MTT)测定( Fig. 1B )。此外,去铁胺(DFO;一种铁螯合剂)、铁他汀 1(Fer-1;一种脂质过氧化抑制剂)可以完全消除 IKE 诱导的铁死亡细胞死亡,但不能被 Z-VAD-fmk(一种泛半胱天冬酶抑制剂)消除。 Fig. 1B ),表明游离铁积累和脂质过氧化在促进铁死亡中的重要性。与铁死亡依赖性细胞活力下降一致,在 IKE 处理的NFE2L2/NRF2 KO 细胞中也观察到较高水平的脂质过氧化物,当细胞与 DFO 共同处理时,这种情况可以逆转。 Fig. 1C )。接下来,通过评估关键铁死亡标记物进一步证实,与NFE2L2/NRF2 WT 细胞相比,IKE 处理的NFE2L2/NRF2 KO 细胞中铁死亡更多,包括前列腺素内过氧化物合酶 2 ( PTGS2 ) 及其蛋白质产物环加氧酶 2 的 mRNA 水平较高(COX2) ( Fig. 1, D and E ),以及增加 4-羟基壬烯醛 (4-HNE) 蛋白质加合物的形成( Fig. 1D )。此外,在未经处理的条件下, NFE2L2/NRF2 KO细胞的总GSH水平降低,活性氧(ROS)水平升高,丙二醛(MDA)形成更多。 Fig. 1, F to H ); IKE 处理进一步加剧了NFE2L2/NRF2 WT 和 KO 细胞之间这些测量结果的差异( Fig. 1, F to H )。 当使用特异性较低的铁死亡诱导剂 SAS 时,也获得了类似的结果(图 S1,C 至 J)。

Fig. 1. NFE2L2/NRF2 deletion sensitizes ovarian cancer cells to ferroptosis.

图 1. NFE2L2/NRF2缺失使卵巢癌细胞对铁死亡敏感。

(A) WT or three individual CRISPR NFE2L2/NRF2 KO SKOV-3 ovarian cancer cell lines were left untreated or treated with IKE (10 μM), and cell growth was monitored using the IncuCyte imaging system. Results shown here were at 24 hours after treatment. Ferroptotic cells were identified on the basis of ferroptotic cell morphology (ballooning). More than 1000 cells were counted, and the percentage of ferroptotic cells was plotted. Scale bar, 50 μm. (B) NFE2L2/NRF2 WT and KO cell lines were cotreated with DFO (100 μM), Fer-1 (10 μM), or Z-VAD-fmk (20 μM), alone with DMSO or IKE (10 μM) for 24 hours. Cell viability was measured by MTT assay. ns, not significant. (C to H) NFE2L2/NRF2 WT and KO cell lines were treated with 10 μM IKE for 12 hours before the following end points were measured: (C) Lipid peroxide production was assessed by flow cytometry using C11-BODIPY581/591. DFO cotreatment: 100 μM, 12 hours. (D) 4-Hydroxynonenal (4-HNE) protein adducts and COX2 protein levels were measured by immunoblot analysis. (E) mRNA levels of PTGS2 were measured by quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR). (F) Total intracellular GSH levels were measured by QuantiChrom GSH assay. (G) ROS were measured by electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) spectroscopy. (H) Malondialdehyde (MDA) formation was detected colorimetrically using the thiobarbituric acid reactive substance (TBARS) assay. Data are represented as means ± SEM of three biological replicates. n = 3; *P < 0.05.

( A ) WT 或三个单独的 CRISPR NFE2L2/NRF2 KO SKOV-3 卵巢癌细胞系未经处理或用 IKE (10 μM) 处理,并使用 IncuCyte 成像系统监测细胞生长。这里显示的结果是治疗后 24 小时的结果。根据铁死亡细胞形态(气球状)来鉴定铁死亡细胞。对超过 1000 个细胞进行计数,并绘制铁死亡细胞的百分比。比例尺,50 μm。 ( B ) NFE2L2/NRF2 WT 和 KO 细胞系用 DFO (100 μM)、Fer-1 (10 μM) 或 Z-VAD-fmk (20 μM) 共同处理,单独用 DMSO 或 IKE (10 μM) 处理 24 小时。小时。通过MTT测定来测量细胞活力。 ns,不显着。 ( C到H ) NFE2L2/NRF2 WT 和 KO 细胞系用 10 μM IKE 处理 12 小时,然后测量以下终点: (C) 使用 C11-BODIPY 581/591通过流式细胞术评估脂质过氧化物的产生。 DFO 共处理:100 μM,12 小时。 (D) 通过免疫印迹分析测量 4-羟基壬烯醛 (4-HNE) 蛋白加合物和 COX2 蛋白水平。 (E) 通过定量逆转录聚合酶链反应 (qRT-PCR) 测量PTGS2的 mRNA 水平。 (F) 通过 QuantiChrom GSH 测定法测量细胞内总 GSH 水平。 (G) 通过电子顺磁共振 (EPR) 光谱测量 ROS。 (H) 使用硫代巴比妥酸反应物质 (TBARS) 测定法以比色法检测丙二醛 (MDA) 的形成。数据表示为三个生物重复的平均值±SEM。 n = 3; * P < 0.05。

Table 1. The percentage of ferroptotic cells following IKE treatment (10 μM, 24 hours).

表 1. IKE 处理(10 μM,24 小时)后铁死亡细胞的百分比。

| Cell line 细胞系 | % Ferroptotic cells % 铁死亡细胞 |

|---|---|

| NRF2 WT NRF2野生型 | 18.66 ± 2.6 18.66±2.6 |

| NRF2 KO-1 | 71.15 ± 5.2 71.15±5.2 |

| NRF2 KO-2 | 79 ± 7.2 79±7.2 |

| NRF2 KO-3 | 78 ± 7.9 78±7.9 |

| NRF2 KO-1,2,3 | 76.05 ± 6.76 76.05±6.76 |

| VAMP8 KO | 40 ± 5.28 40±5.28 |

| HERC2 KO | 42 ± 6.35 42±6.35 |

| DKO | 71.25 ± 9.35 71.25±9.35 |

NFE2L2/NRF2 deletion impairs iron homeostasis and increases the LIP through depletion of its target gene HERC2

NFE2L2/NRF2缺失会损害铁稳态,并通过消除其靶基因HERC2来增加 LIP

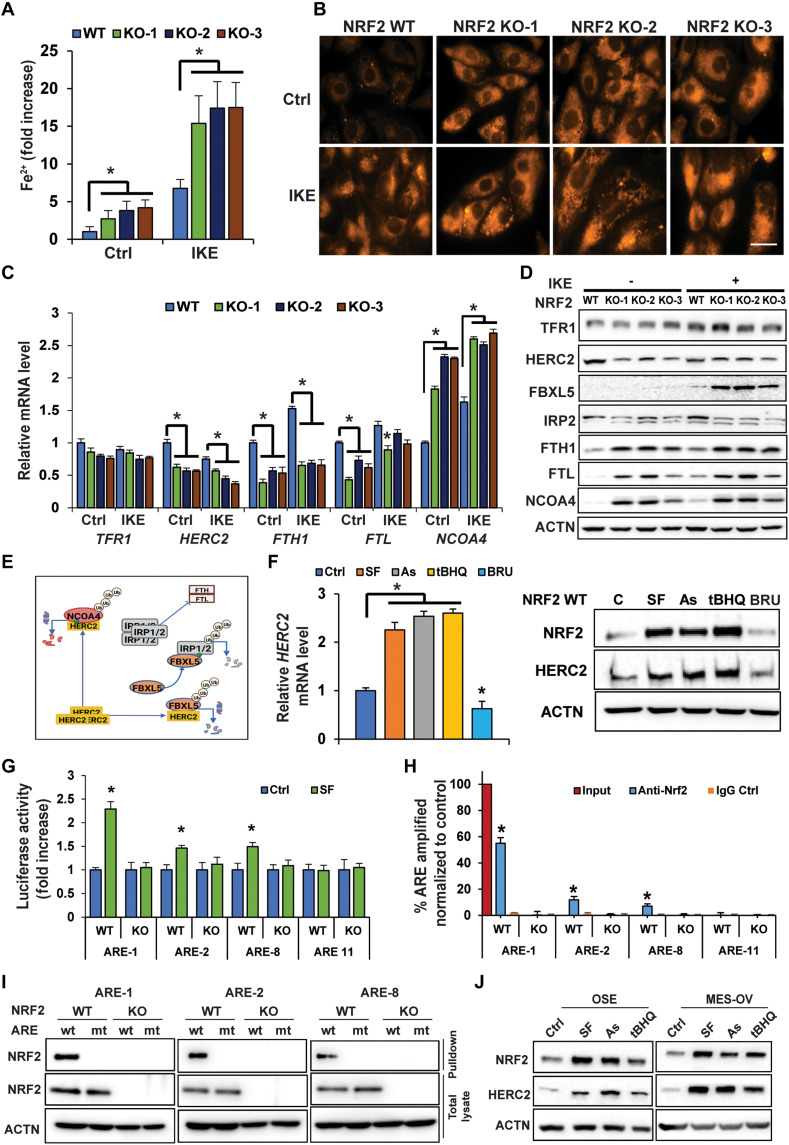

As free iron (ferrous iron, Fe2+) is required to drive ferroptotic cell death, the intracellular Fe2+ concentration was determined using a Ferene-S–based colorimetric assay. Basal intracellular Fe2+ levels increased ~3- to 5-fold in NFE2L2/NRF2 KO compared to NFE2L2/NRF2 WT cells; IKE treatment further enhanced free Fe2+ levels (Fig. 2A). Increased free iron levels in NFE2L2/NRF2 KO cells under both untreated and IKE-treated conditions were verified by immunofluorescence using the Fe2+-sensitive probe FerroOrange (Fig. 2B). Please note that IKE treatment led to an increase in free Fe2+ levels even in NFE2L2/NRF2 WT control cells, which is consistent with previous reports when cells were treated with erastin (22, 37). Next, expression of genes critical in maintaining iron homeostasis was compared in NFE2L2/NRF2 WT versus KO cells. Transferrin receptor 1 (TFRC/TFR1), the primary receptor controlling iron uptake, was moderately induced by IKE treatment at the protein but not mRNA level in all the cell lines, whereas there was a slight reduction in TFRC/TFR1 mRNA levels, but not protein, in all NFE2L2/NRF2 KO cells compared to NFE2L2/NRF2 WT cells (Fig. 2, C and D). In contrast, NFE2L2/NRF2 KO altered the expression of many proteins involved in ferritin synthesis and degradation [HERC2, F-box and leucine-rich repeat protein 5 (FBXL5), iron regulatory protein 2 (IRP2), and NCOA4] (Fig. 2, C and D), which in turn would affect the LIP. First, NFE2L2/NRF2 KO affected ferritin synthesis as evidenced by the following findings: NFE2L2/NRF2 KO cells exhibited altered levels of key iron sensor proteins constituting the HERC2-FBXL5-IRP1/2-FTH1/FTL pathway, including decreased HERC2, increased FBXL5, decreased IRP2, and increased ferritin heavy/light chains (FTH1 and FTL) (Fig. 2D). As shown in the model (Fig. 2E), HERC2 is an E3 ubiquitin ligase for both FBXL5 and NCOA4; however, HERC2 binds FBXL5 in the absence of free iron (Fe2+), whereas HERC2 binds NCOA4 only in the presence of free iron (38–41). In addition, IRP2 binds to the iron-responsive element in the 5′ untranslated region of FTH1 and FTL mRNA to repress the synthesis of ferritin during low free iron conditions. Thus, this NFE2L2/NRF2 deletion–mediated decrease in IRP2 should ultimately result in enhanced synthesis of ferritin in NFE2L2/NRF2-KO SKOV-3 cells. Consistent with this notion, increased protein levels of both FTH1 and FTL were observed (Fig. 2D) although their mRNA expression decreased (Fig. 2C), which was in accordance with FTH1/FTL being NRF2 target genes (42). Second, NFE2L2/NRF2 KO also affected ferritin degradation. NCOA4 is a critical cargo receptor that specifically recruits ferritin to the autophagosome for degradation, a process termed ferritinophagy (43). Both the mRNA and protein levels of NCOA4 were increased in NFE2L2/NRF2 KO cells (Fig. 2, C and D). The increased NCOA4 protein level seen in NFE2L2/NRF2 KO cells was partly due to decreased expression of HERC2, resulting in its stabilization (Fig. 2, D and E). Collectively, these results indicate that NFE2L2/NRF2 deletion impairs iron homeostasis by altering expression of proteins controlling ferritin synthesis and degradation, resulting in an increased LIP and enhanced sensitivity of cancer cells to ferroptosis.

由于需要游离铁(二价铁,Fe 2+ )来驱动铁死亡细胞死亡,因此使用基于 Ferene-S 的比色测定法测定细胞内 Fe 2+浓度。与NFE2L2/NRF2 WT 细胞相比, NFE2L2/NRF2 KO 细胞中基础细胞内 Fe 2+水平增加约 3 至 5 倍; IKE 处理进一步提高了游离 Fe 2+水平( Fig. 2A )。使用 Fe 2+敏感探针 FerroOrange 通过免疫荧光验证了未经处理和 IKE 处理条件下NFE2L2/NRF2 KO 细胞中游离铁水平的增加( Fig. 2B )。请注意,即使在NFE2L2/NRF2 WT 对照细胞中,IKE 处理也会导致游离 Fe 2+水平增加,这与之前用erastin 处理细胞时的报告一致( 22 , 37 )。接下来,比较了NFE2L2/NRF2 WT 和 KO 细胞中维持铁稳态的关键基因的表达。转铁蛋白受体 1 ( TFRC /TFR1) 是控制铁摄取的主要受体,在所有细胞系中,IKE 处理在蛋白质水平(而非 mRNA 水平)中度诱导,而TFRC /TFR1 mRNA 水平略有降低,但没有降低。与NFE2L2/NRF2 WT 细胞相比,所有NFE2L2/NRF2 KO 细胞中的蛋白质( Fig. 2, C and D )。相比之下, NFE2L2/NRF2 KO 改变了许多参与铁蛋白合成和降解的蛋白质的表达 [HERC2、F-box 和富含亮氨酸的重复蛋白 5 (FBXL5)、铁调节蛋白 2 (IRP2) 和 NCOA4]。 Fig. 2, C and D ),这反过来又会影响 LIP。 首先, NFE2L2/NRF2 KO影响铁蛋白合成,如下结果所证明: NFE2L2 / NRF2 KO细胞表现出构成HERC2-FBXL5-IRP1/2-FTH1/FTL途径的关键铁传感器蛋白水平改变,包括HERC2减少、FBXL5增加,IRP2 减少,铁蛋白重链/轻链(FTH1 和 FTL)增加( Fig. 2D )。如模型所示( Fig. 2E ),HERC2 是 FBXL5 和 NCOA4 的 E3 泛素连接酶;然而,HERC2 在没有游离铁 (Fe 2+ ) 的情况下结合 FBXL5,而 HERC2 仅在存在游离铁的情况下结合 NCOA4 ( 38 – 41 )。此外,IRP2 与FTH1和FTL mRNA 5' 非翻译区的铁响应元件结合,在低游离铁条件下抑制铁蛋白的合成。因此,这种NFE2L2/NRF2缺失介导的 IRP2 减少最终应导致NFE2L2/NRF2 -KO SKOV-3 细胞中铁蛋白的合成增强。与这一观点一致,观察到 FTH1 和 FTL 的蛋白质水平增加( Fig. 2D )尽管它们的 mRNA 表达降低了( Fig. 2C ),这与FTH1 / FTL是 NRF2 靶基因一致( 42 )。其次, NFE2L2/NRF2 KO 也影响铁蛋白降解。 NCOA4 是一种关键的货物受体,专门将铁蛋白招募到自噬体进行降解,这一过程称为铁蛋白自噬。 43 )。 NFE2L2/NRF2 KO 细胞中 NCOA4 的 mRNA 和蛋白水平均增加( Fig. 2, C and D )。 NFE2L2/NRF2 KO 细胞中 NCOA4 蛋白水平增加的部分原因是 HERC2 表达减少,从而导致其稳定化。 Fig. 2, D and E )。总的来说,这些结果表明, NFE2L2/NRF2缺失通过改变控制铁蛋白合成和降解的蛋白质表达来损害铁稳态,导致 LIP 增加并增强癌细胞对铁死亡的敏感性。

Fig. 2. NFE2L2/NRF2 deletion impairs iron homeostasis and increases the LIP through depletion of its target gene HERC2.

图 2. NFE2L2 / NRF2缺失会损害铁稳态,并通过去除其靶基因HERC2来增加 LIP。

(A and B) NFE2L2/NRF2 WT and KO SKOV-3 cell lines were treated with 10 μM IKE for 12 hours before the LIP was measured by (A) Ferene-S absorbance (*P < 0.05, n = 3) or (B) FerroOrange immunofluorescence. Scale bar, 25 μm. (C and D) mRNA or protein levels of genes involved in iron metabolism/storage were measured in NFE2L2/NRF2 WT and NFE2L2/NRF2 KO SKOV-3 cells treated with IKE (10 μM, 12 hours) by (C) qRT-PCR (*P < 0.05, n = 3) or (D) immunoblot analysis. (E) Model showing HERC2 regulation of ferritin synthesis and NCOA4-mediated ferritin degradation. Green dot = ferrous iron; Ub, ubiquitin. (F) HERC2 mRNA (right; *P < 0.05, n = 3) and protein levels (left) in NFE2L2/NRF2 WT SKOV-3 cells treated with DMSO (Ctrl), sulforaphane (SF; 5 μM), arsenic (As; 1 μM), tert-butylhydroquinone (tBHQ; 25 μM), or brusatol (BRU; 20 nM) for 12 hours. (G) NFE2L2/NRF2 WT SKOV-3 cells were transfected with the indicated antioxidant response element (ARE) firefly and thymidine kinase renilla luciferase vectors and then treated with DMSO or SF (5 μM) for 12 hours, and luciferase activity was measured. *P < 0.05, n = 3. (H) NRF2-ARE binding was determined via ChIP-PCR. *P < 0.05, n = 3. (I) Biotinylated ARE pulldown of three putative HERC2 WT or mutant (mt) AREs using cell lysate from NFE2L2/NRF2 WT or NFE2L2/NRF2 KO SKOV-3 cells. DNA binding proteins were pulled down using streptavidin beads, and NRF2 was detected by immunoblot analysis. (J) NRF2 and HERC2 protein levels in ovarian surface epithelial (OSE) and MES-OV ovarian cell lines following treatment with SF (5 μM), As (1 μM), or tBHQ (25 μM) for 12 hours.

( A和B ) NFE2L2/NRF2 WT 和 KO SKOV-3 细胞系用 10 μM IKE 处理 12 小时,然后通过 (A) Ferene-S 吸光度测量 LIP(* P < 0.05, n = 3)或( B) 橙铁免疫荧光。比例尺,25 μm。 ( C和D ) 通过 (C) qRT-PCR 测量经 IKE(10 μM,12 小时)处理的NFE2L2/NRF2 WT 和NFE2L2/NRF2 KO SKOV-3 细胞中参与铁代谢/储存的基因的 mRNA 或蛋白质水平(* P < 0.05, n = 3) 或 (D) 免疫印迹分析。 ( E ) 模型显示 HERC2 对铁蛋白合成和 NCOA4 介导的铁蛋白降解的调节。绿点=二价铁; Ub,泛素。 ( F ) 用 DMSO (Ctrl)、萝卜硫素 (SF; 5 μM)、砷 (As) 处理的NFE2L2/NRF2 WT SKOV-3 细胞中的HERC2 mRNA(右;* P < 0.05, n = 3)和蛋白质水平(左) ; 1 μM)、叔丁基氢醌 (tBHQ; 25 μM) 或布鲁萨托 (BRU; 20 nM) 12 小时。 ( G ) NFE2L2/NRF2 WT SKOV-3 细胞用指定的抗氧化反应元件 (ARE) 萤火虫和胸苷激酶海肾荧光素酶载体转染,然后用 DMSO 或 SF (5 μM) 处理 12 小时,并测量荧光素酶活性。 * P < 0.05, n = 3。( H ) NRF2-ARE 结合通过 ChIP-PCR 测定。 * P < 0.05, n = 3。 ( I ) 使用来自NFE2L2/NRF2 WT 或NFE2L2/NRF2 KO SKOV-3 细胞的细胞裂解液对三个假定的 HERC2 WT 或突变体 (mt) ARE 进行生物素化 ARE 下拉。 使用链霉亲和素珠拉下 DNA 结合蛋白,并通过免疫印迹分析检测 NRF2。 ( J ) 用 SF (5 μM)、As (1 μM) 或 tBHQ (25 μM) 处理 12 小时后,卵巢表面上皮 (OSE) 和 MES-OV 卵巢细胞系中的 NRF2 和 HERC2 蛋白水平。

Since both FBXL5-IRP2–mediated ferritin synthesis and NCOA4-dependent ferritin degradation through the autophagy-lysosome pathway can be controlled by the key E3 ubiquitin ligase HERC2 (Fig. 2E) (41, 43), coupled with the result described in Fig. 2D indicating a decrease in HERC2 protein levels in NFE2L2/NRF2 KO cells, the possibility of HERC2 being an NRF2 target gene was explored. Consistent with the observed positive correlation between the protein levels of NRF2 and HERC2 (Fig. 2D), a higher level of HERC2 mRNA in NFE2L2/NRF2 WT cells was observed in both untreated and IKE-treated conditions, compared to NFE2L2/NRF2 KO cells (Fig. 2C). The NRF2 activators sulforaphane (SF), arsenic (As), and tert-butylhydroquinone (tBHQ) or the NRF2 inhibitor brusatol (BRU) was able to increase or decrease both the mRNA and protein level of HERC2, respectively (Fig. 2F). In silico analysis identified 12 putative antioxidant response elements (AREs) in HERC2, which were individually cloned into the promoter region of a firefly luciferase vector, followed by measurement of firefly luciferase activity using a dual luciferase reporter assay (renilla was used as an internal control). Three functional AREs (ARE-1, ARE-2, and ARE-8) were identified as their luciferase activity was enhanced by SF treatment; one nonfunctional ARE (ARE-11) was also included for comparison (Fig. 2G). Endogenous binding of NRF2 to these three AREs was further verified to occur in WT, but not NFE2L2/NRF2 KO, cells by chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP)–polymerase chain reaction (PCR) (Fig. 2H). Last, using biotinylated 41–base pair (bp) DNA probes containing the WT ARE-1, ARE-2, ARE-8, or their mutated ARE sequences (mt-AREs), NRF2 was confirmed to specifically bind to ARE-1, ARE-2, and ARE-8, but not their mutant counterparts (Fig. 2I). These results demonstrate that the HERC2 promoter, intron1, and exon1 contain functional AREs that are regulated by NRF2. In addition, NRF2 activators were able to induce NRF2 and HERC2 protein levels in two additional ovarian cell lines with low basal levels of NRF2 (Fig. 2J). More broadly, a positive correlation between NRF2 and HERC2 was also observed in most ovarian cell lines tested where NFE2L2/NRF2 expression was reduced by transient knockdown using two different NFE2L2/NRF2 small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) (fig. S2).

由于 FBXL5-IRP2 介导的铁蛋白合成和通过自噬-溶酶体途径的 NCOA4 依赖性铁蛋白降解都可以由关键的 E3 泛素连接酶 HERC2 控制( Fig. 2E ) ( 41 , 43 ),加上中描述的结果 Fig. 2D 表明NFE2L2/NRF2 KO 细胞中 HERC2 蛋白水平降低,探讨了HERC2作为 NRF2 靶基因的可能性。与观察到的 NRF2 和 HERC2 蛋白水平之间的正相关性一致( Fig. 2D ),与NFE2L2/NRF2 KO 细胞相比,在未经处理和 IKE 处理的条件下, NFE2L2/NRF2 WT 细胞中的HERC2 mRNA 水平较高( Fig. 2C )。 NRF2 激活剂萝卜硫素 (SF)、砷 (As) 和叔丁基氢醌 (tBHQ) 或 NRF2 抑制剂布鲁萨醇 (BRU) 能够分别增加或减少 HERC2 的 mRNA 和蛋白质水平。 Fig. 2F )。计算机分析确定了HERC2中的 12 个假定的抗氧化反应元件 (ARE),将其单独克隆到萤火虫荧光素酶载体的启动子区域,然后使用双荧光素酶报告基因测定(使用海肾作为内部对照)测量萤火虫荧光素酶活性)。确定了三种功能性 ARE(ARE-1、ARE-2 和 ARE-8),因为 SF 处理增强了它们的荧光素酶活性;还包括一种非功能性 ARE (ARE-11) 进行比较( Fig. 2G )。通过染色质免疫沉淀 (ChIP)-聚合酶链式反应 (PCR) 进一步证实 NRF2 与这三种 ARE 的内源性结合发生在 WT 细胞中,但在NFE2L2/NRF2 KO 细胞中则不然。 Fig. 2H )。 最后,使用含有 WT ARE-1、ARE-2、ARE-8 或其突变 ARE 序列 (mt-ARE) 的生物素化 41 碱基对 (bp) DNA 探针,证实 NRF2 与 ARE-1 特异性结合, ARE-2 和 ARE-8,但不是它们的突变对应物( Fig. 2I )。这些结果表明, HERC2启动子、内含子 1 和外显子 1 含有受 NRF2 调控的功能性 ARE。此外,NRF2 激活剂能够在另外两种 NRF2 基础水平较低的卵巢细胞系中诱导 NRF2 和 HERC2 蛋白水平( Fig. 2J )。更广泛地说,在大多数测试的卵巢细胞系中也观察到 NRF2 和 HERC2 之间的正相关性,其中使用两种不同的NFE2L2/NRF2小干扰 RNA (siRNA) 进行瞬时敲低, NFE2L2/NRF2表达降低(图 S2)。

VAMP8 down-regulation in NFE2L2/NRF2 KO cells results in a defect of ferritinophagy and autophagosomal accumulation of apoferritin/NCOA4

NFE2L2 / NRF2 KO细胞中VAMP8下调导致铁蛋白自噬缺陷和脱铁铁蛋白/NCOA4自噬体积累

As shown in Fig. 2D, the protein levels of FTH1, FTL, and NCOA4 were increased in NFE2L2/NRF2 KO cells, indicative of a defect in ferritin degradation. Since ferritin is degraded by the autophagy-lysosome pathway, a process termed ferritinophagy (see a model illustration for ferritinophagy in Fig. 3A), this prompted us to examine the possibility that the observed increase in these proteins was a result of blockage of autophagic flux. NFE2L2/NRF2 KO cells exhibited a larger number of microtubule-associated protein 1A/1B-light chain 3 (LC3)–positive autophagosomes, but not autolysosomes, as assessed by monomeric–red fluorescent protein (mRFP)–green fluorescent protein (GFP)–LC3 tandem–based immunofluorescence (Fig. 3B). This result indicates that there was no defect in autophagosome formation, but instead a blockage at the later stage of the pathway in NFE2L2/NRF2 KO cells. Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) also indicated an accumulation of protein aggregates and double-membrane autophagosomes in NFE2L2/NRF2 KO cells (Fig. 3C). Next, the snap receptor (SNARE) complex [VAMP8, synaptosome-associated protein 29 (SNAP29), and syntaxin (STX17)], which plays a critical role in mediating autophagosome-lysosome fusion (44), was examined. Unexpectedly, the protein level of VAMP8, a lysosomal SNARE protein, was markedly reduced, while there were no obvious changes in STX17 or SNAP29 protein levels in NFE2L2/NRF2 KO cells (Fig. 3D). Furthermore, NFE2L2/NRF2 KO cells had ~30 to 40% lower VAMP8 mRNA levels compared to WT cells (Fig. 3E). Transcription of lysosomal genes has been shown to be regulated by transcription factor EB (TFEB), whose activity is controlled by serine phosphorylation. Previous studies indicate that phosphorylation at S142/S138 inactivates TFEB by enhancing its nuclear export, whereas S211 phosphorylation mediates cytosolic retention. Thus, the net effect of TFEB phosphorylation at these sites is less nuclear localization and reduced transcription of lysosomal genes (45–49). Therefore, the phosphorylation status of TFEB and mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR), one of the upstream kinases for TFEB, were assessed. Basal phosphorylation of mTOR at S2448 was higher in NFE2L2/NRF2 KO cells, while the total mTOR level remained unchanged; TFEB phosphorylation was also enhanced at S211 and S142 with no changes in its total protein expression (Fig. 3F). Consistently, when cells with nuclear localization of TFEB were counted, significantly more cells with nuclear TFEB localization in NFE2L2/NRF2 WT cells than NFE2L2/NRF2 KO cells were identified (Fig. 3G). TFEB binds to DNA sequences containing an EBOX motif (CANNTG), and in silico analysis identified six putative EBOX motifs in the promoter region of VAMP8. Using a dual luciferase assay, one functional EBOX (−1932CACTTG−1927) was identified, as demonstrated by increased EBOX-driven firefly luciferase activity in the presence of mTOR inhibitors (torin and rapamycin) and adenosine monophosphate–activated protein kinase (AMPK) activator (AICAR), as well as a decreased luciferase activity following mTOR activation (amino acids) (Fig. 3H). These results indicate that NFE2L2/NRF2 KO leads to ferritinophagy blockage through TFEB phosphorylation and nuclear exclusion, which decreases the transcription of VAMP8, although the precise mechanism by which deletion of NFE2L2/NRF2 leads to activation of mTOR, or possibly other kinases that may regulate TFEB phosphorylation and nuclear localization, requires further investigation. The notion that mTOR was activated in NFE2L2/NRF2 KO cells, resulting in decreased VAMP8 transcription, was further supported by the results in fig. S3. Rapamycin treatment reduced phosphorylated mTOR levels in NFE2L2/NRF2 KO cells without affecting the total mTOR level, indicating inactivation of mTOR by rapamycin in NFE2L2/NRF2 KO cells. Rapamycin increased VAMP8 expression in NFE2L2/NRF2 KO cells, which partially rescued the blockage of ferritinophagy flux as indicated by the reduced level of NCOA4, p62, and LC3-II in rapamycin-treated NFE2L2/NRF2 KO cells (fig. S3C). Similar to DFO, rapamycin also reduced the number of ferroptotic cells (fig. S3A) and improved cell survival in response to SAS in NFE2L2/NRF2 KO cells (fig. S3B). Similar to HERC2, the positive correlation between NRF2 and VAMP8 in a variety of ovarian cell lines was also observed when NFE2L2/NRF2 expression was reduced by NFE2L2/NRF2 siRNAs (fig. S2). Immortalized normal ovarian surface epithelial (OSE) (50) and fallopian tube (FT-246) (51) cell lines had a low basal protein level of NRF2 and an undetectable level of VAMP8, while NFE2L2/NRF2 knockdown in the ovarian cancer cell lines tested all resulted in a decrease in VAMP8 (fig. S2).

如图所示 Fig. 2D , NFE2L2/NRF2 KO 细胞中 FTH1、FTL 和 NCOA4 的蛋白水平增加,表明铁蛋白降解存在缺陷。由于铁蛋白通过自噬-溶酶体途径降解,这一过程称为铁蛋白自噬(参见铁蛋白自噬的模型说明) Fig. 3A ),这促使我们研究观察到的这些蛋白质的增加是否是自噬流受阻的结果。通过单体-红色荧光蛋白 (mRFP)-绿色荧光蛋白 (GFP) 评估, NFE2L2/NRF2 KO 细胞表现出大量微管相关蛋白 1A/1B-轻链 3 (LC3) 阳性自噬体,但没有自溶酶体–LC3 串联免疫荧光( Fig. 3B )。这一结果表明, NFE2L2/NRF2 KO细胞中自噬体形成并没有缺陷,而是在该通路的后期被阻断。透射电子显微镜 (TEM) 还表明NFE2L2/NRF2 KO 细胞中蛋白质聚集体和双膜自噬体的积累。 Fig. 3C )。接下来是 snap 受体 (SNARE) 复合物 [VAMP8、突触体相关蛋白 29 (SNAP29) 和突触蛋白 (STX17)],它在介导自噬体 - 溶酶体融合中发挥着关键作用。 44 ),进行了检查。出乎意料的是, NFE2L2/NRF2 KO细胞中溶酶体SNARE蛋白VAMP8的蛋白水平显着降低,而STX17或SNAP29蛋白水平没有明显变化。 Fig. 3D )。此外,与 WT 细胞相比, NFE2L2/NRF2 KO 细胞的VAMP8 mRNA 水平降低约 30% 至 40%( Fig. 3E )。 溶酶体基因的转录已被证明受到转录因子 EB (TFEB) 的调节,其活性由丝氨酸磷酸化控制。先前的研究表明,S142/S138 的磷酸化通过增强 TFEB 的核输出而使其失活,而 S211 磷酸化则介导细胞质保留。因此,这些位点 TFEB 磷酸化的净效应是核定位减少和溶酶体基因转录减少。 45 – 49 )。因此,评估了 TFEB 和哺乳动物雷帕霉素靶蛋白 (mTOR)(TFEB 上游激酶之一)的磷酸化状态。 NFE2L2/NRF2 KO 细胞中 mTOR 在 S2448 的基础磷酸化较高,而总 mTOR 水平保持不变; TFEB 磷酸化也在 S211 和 S142 处增强,但其总蛋白表达没有变化( Fig. 3F )。一致地,当对具有 TFEB 核定位的细胞进行计数时,发现NFE2L2/NRF2 WT 细胞中具有核 TFEB 定位的细胞明显多于NFE2L2/NRF2 KO 细胞( Fig. 3G )。 TFEB 与含有 EBOX 基序 (CANNTG) 的 DNA 序列结合,并通过计算机分析在VAMP8启动子区域鉴定出六个假定的 EBOX 基序。使用双荧光素酶测定,鉴定出一个功能性 EBOX ( -1932 CACTTG -1927 ),这通过在 mTOR 抑制剂(torin 和雷帕霉素)和腺苷单磷酸激活蛋白激酶 (AMPK) 存在的情况下 EBOX 驱动的萤火虫荧光素酶活性增加来证明。激活剂 (AICAR),以及 mTOR 激活(氨基酸)后荧光素酶活性降低( Fig. 3H )。 这些结果表明, NFE2L2/NRF2 KO 通过 TFEB 磷酸化和核排斥导致铁蛋白自噬阻断,从而降低VAMP8的转录,尽管删除NFE2L2/NRF2导致 mTOR 或可能调节的其他激酶激活的精确机制TFEB磷酸化和核定位,需要进一步研究。 mTOR 在NFE2L2/NRF2 KO 细胞中被激活,导致 VAMP8 转录减少,这一观点得到了图 2 中结果的进一步支持。 S3。雷帕霉素处理降低了NFE2L2/NRF2 KO 细胞中的磷酸化 mTOR 水平,但不影响总 mTOR 水平,表明雷帕霉素在NFE2L2/NRF2 KO 细胞中使 mTOR 失活。雷帕霉素增加了NFE2L2 / NRF2 KO 细胞中 VAMP8 的表达,这部分缓解了铁蛋白自噬流的阻断,如雷帕霉素处理的NFE2L2/NRF2 KO 细胞中 NCOA4、p62 和 LC3-II 水平降低所示(图 S3C)。与 DFO 类似,雷帕霉素还减少了NFE2L2/NRF2 KO 细胞中铁死亡细胞的数量(图 S3A),并提高了 SAS 对 SAS 的细胞存活率(图 S3B)。与HERC2类似,当NFE2L2/NRF2 siRNA减少NFE2L2/NRF2表达时,在多种卵巢细胞系中也观察到NRF2和VAMP8之间的正相关性(图S2)。 永生化正常卵巢表面上皮(OSE)( 50 )和输卵管(FT-246)( 51 )细胞系的 NRF2 基础蛋白水平较低,VAMP8 水平不可检测,而测试的卵巢癌细胞系中NFE2L2/NRF2敲低均导致 VAMP8 减少(图 S2)。

Fig. 3. VAMP8 down-regulation in NFE2L2/NRF2 KO cells results in a defect of ferritinophagy and autophagosomal accumulation of apoferritin/NCOA4.

图 3. NFE2L2/NRF2 KO 细胞中VAMP8下调导致铁蛋白自噬缺陷和脱铁铁蛋白/NCOA4 自噬体积累。

(A) Illustration of the ferritinophagy pathway. (B) Immunofluorescence analysis of autophagy flux in NFE2L2/NRF2 WT and NFE2L2/NRF2 KO SKOV-3 cells transfected with an mRFP-GFP-LC3 tandem reporter for 24 hours. Yellow puncta, autophagosomes; red puncta, autolysosomes. Scale bar, 10 μm. (C) Representative TEM micrographs of WT and NFE2L2/NRF2 KO cells. Arrows indicate autophagosomes or protein aggregates. (D) Protein levels of three SNARE proteins that direct autophagosome-lysosome fusion. (E) VAMP8 mRNA levels in NFE2L2/NRF2 WT and KO cells. *P < 0.05, n = 3. (F) Total or phosphorylated protein levels of mTOR and TFEB. (G) Nuclear localization of TFEB was detected by indirect immunofluorescence (top); 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) was used for nuclear staining, and the number of TFEB nuclear-positive cells was counted and plotted (bottom). *P < 0.05, n = 3. Scale bar, 50 μm. (H) One functional EBOX in the promoter of VAMP8 was identified. The 41-bp EBOX-containing sequence was shown above. Relative EBOX luciferase activity was measured by dual luciferase assay, following treatment with mTOR inhibitors [torin, 100 nM, 24 hours; rapamycin (Rap), 1 μM, 24 hours; and AICAR, 1 mM, 4 hours] or mTOR activation by amino acids (AA). (I and J) Indirect immunofluorescence of (I) FTH1 and LC3, and (J) FTH1 and LAMP1 in NFE2L2/NRF2 WT or KO SKOV-3 cells. Inset shows magnified puncta. (K) Cells were treated with or without ferric ammonium citrate (FAC; 100 μM, 12 hours). Ferric iron deposits were assessed by Perls Prussian blue staining, followed by indirect immunofluorescence of FTH1/LC3. Scale bars, 10 μm.

( A ) 铁蛋白自噬途径的图示。 ( B ) 对用 mRFP-GFP-LC3 串联报告基因转染 24 小时的NFE2L2/NRF2 WT 和NFE2L2/NRF2 KO SKOV-3 细胞中的自噬流进行免疫荧光分析。黄色斑点,自噬体;红色点,自溶酶体。比例尺,10 μm。 ( C ) WT 和NFE2L2/NRF2 KO 细胞的代表性 TEM 显微照片。箭头表示自噬体或蛋白质聚集体。 ( D ) 指导自噬体-溶酶体融合的三种 SNARE 蛋白的蛋白水平。 ( E ) NFE2L2/NRF2 WT 和 KO 细胞中的VAMP8 mRNA 水平。 * P < 0.05, n = 3。 ( F ) mTOR 和 TFEB 的总蛋白或磷酸化蛋白水平。 ( G ) 通过间接免疫荧光检测 TFEB 的核定位(上);使用 4',6-二脒基-2-苯基吲哚 (DAPI) 进行核染色,并对 TFEB 核阳性细胞的数量进行计数并绘制(底部)。 * P < 0.05, n = 3。比例尺,50 μm。 ( H ) VAMP8启动子中的一个功能性 EBOX 被鉴定。包含 41 bp EBOX 的序列如上所示。在用 mTOR 抑制剂 [torin,100 nM,24 小时;torin,100 nM,24 小时;雷帕霉素 (Rap),1 μM,24 小时;和AICAR,1 mM,4小时]或通过氨基酸(AA)激活mTOR。 ( I和J ) NFE2L2/NRF2 WT 或 KO SKOV-3 细胞中 (I) FTH1 和 LC3 以及 (J) FTH1 和 LAMP1 的间接免疫荧光。插图显示放大的斑点。 ( K ) 用或不用柠檬酸铁铵(FAC;100 μM,12 小时)处理细胞。通过 Perls 普鲁士蓝染色评估三价铁沉积物,然后进行 FTH1/LC3 间接免疫荧光。比例尺,10 μm。

We have shown that decreased HERC2 expression led to enhanced protein synthesis of FTH1/FTL and enhanced NCOA4 protein stability, and that decreased VAMP8 expression resulted in ferritinophagy blockage in NFE2L2/NRF2 KO cells. Next, the effect of NFE2L2/NRF2 deletion on autophagic ferritin turnover and intracellular free iron was assessed. Immunofluorescence analysis revealed that while WT cells had very little FTH1/FTL signal (less ferritin aggregates shown as puncta), NFE2L2/NRF2 KO cells had significantly more FTH1/FTL aggregates, most of which colocalized with LC3-positive puncta (Fig. 3I, Table 2, and fig. S4A). However, while FTH1/FTL colocalized with LC3, indicating recruitment of ferritin to the autophagosome, FTH1/FTL failed to be delivered to the lysosome, as very few FTH1/FTL aggregates colocalized with LAMP1-positive lysosomes in NFE2L2/NRF2 KO cells (Fig. 3J, Table 2, and fig. S4B). These results support a model whereby FTH1/FTL was recruited by NCOA4 into autophagosomes, which then accumulated due to the blockage of VAMP8-mediated autophagosome-lysosome fusion in NFE2L2/NRF2 KO cells. In addition, accumulation of FTH1 aggregates was observed in other ovarian cell lines where NFE2L2/NRF2 was knocked down via siRNA (fig. S4C). Paradoxically, enhanced ferritin synthesis and blockage of ferritin degradation (inhibition of ferritinophagy) in NFE2L2/NRF2 KO cells should have resulted in a decrease, rather than a significant increase, of the LIP (Fig. 2, A and B). We hypothesized that the availability of higher than normal NCOA4, a critical cargo receptor that recruits ferritin to the autophagosome, would overwhelm the other proteins, such as poly(RC) binding protein 1 (PCBP1), needed to deliver iron to ferritin (52), resulting in NCOA4-mediated recruitment of apoferritin into the autophagosome. As shown in Fig. 3K, NFE2L2/NRF2 WT cells showed an increase in Perls staining (dark dots in the cytosol) after ferric ammonium citrate (FAC) treatment, indicative of ferric iron stored in ferritin cages, while the NFE2L2/NRF2 KO cells had very limited Perls staining after FAC treatment, although these cells contained many ferritin aggregates colocalized with LC3 (Fig. 3K), indicating recruitment of apoferritin into autophagosomes in NFE2L2/NRF2 KO cells. This result suggests that the excessive amount of NCOA4 resulted in the rapid recruitment of apoferritin into autophagosomes before iron incorporation into the ferritin complex. Next, the effect of siRNA-mediated knockdown of NCOA4 on alleviating the increased LIP and ferroptosis observed in NFE2L2/NRF2 KO cells was tested. NCOA4-siRNA had a slight effect on the protein levels of FTH1/FTL (increased) and LC3-I/LC3-II (decreased) in both the WT and KO cell lines (fig. S4D). Knockdown of NCOA4 alleviated 4-HNE–adducted protein formation in IKE-treated NFE2L2/NRF2 KO cells (fig. S4, D and E). The protection afforded by NCOA4 knockdown in NFE2L2/NRF2 KO cells was also visualized by a reduction in FTH1 puncta formation, decreased Fe2+-sensitive FerroOrange fluorescence intensity, and fewer cells undergoing ferroptotic death (fig. S4F). Consistent with these results, NCOA4 knockdown significantly enhanced the survival of NFE2L2/NRF2 KO cells under IKE treatment (fig. S4G). In addition, the mRNA levels of ferroportin (SLC40A1) were significantly higher in the NFE2L2/NRF2 KO cells compared to WT (fig. S4H), demonstrating that the accumulation of free labile iron observed in the NFE2L2/NRF2 KO cells is most likely not due to changes in ferroportin expression, despite previous reports (53).

我们发现, HERC2表达减少导致 FTH1/FTL 蛋白合成增强,NCOA4 蛋白稳定性增强, VAMP8表达减少导致NFE2L2/NRF2 KO 细胞中铁蛋白自噬阻断。接下来,评估了NFE2L2/NRF2缺失对自噬铁蛋白周转和细胞内游离铁的影响。免疫荧光分析显示,虽然 WT 细胞具有非常少的 FTH1/FTL 信号(较少的铁蛋白聚集体,显示为斑点),但NFE2L2/NRF2 KO 细胞具有明显更多的 FTH1/FTL 聚集体,其中大多数与 LC3 阳性斑点共定位。 Fig. 3I , Table 2 ,和图。 S4A)。然而,虽然 FTH1/FTL 与 LC3 共定位,表明铁蛋白被招募到自噬体,但 FTH1/FTL 未能被递送至溶酶体,因为在NFE2L2/NRF2 KO 细胞中,很少有 FTH1/FTL 聚集体与 LAMP1 阳性溶酶体共定位。 Fig. 3J , Table 2 ,和图。 S4B)。这些结果支持这样的模型:FTH1/FTL被NCOA4招募到自噬体中,然后由于VAMP8介导的自噬体-溶酶体融合在NFE2L2/NRF2 KO细胞中被阻断而积累。此外,在通过 siRNA 敲除NFE2L2/NRF2 的其他卵巢细胞系中观察到 FTH1 聚集体的积累(图 S4C)。矛盾的是, NFE2L2/NRF2 KO 细胞中铁蛋白合成的增强和铁蛋白降解的阻断(铁蛋白自噬的抑制)应该导致 LIP 的减少,而不是显着增加。 Fig. 2, A and B )。 我们假设,NCOA4(一种将铁蛋白招募到自噬体的关键货物受体)的可用性高于正常水平,将压倒其他蛋白质,例如将铁传递到铁蛋白所需的聚(RC)结合蛋白 1 (PCBP1)。 52 ),导致 NCOA4 介导的脱铁铁蛋白募集到自噬体中。如图所示 Fig. 3K , NFE2L2/NRF2 WT 细胞在柠檬酸铁铵 (FAC) 处理后显示 Perls 染色增加(细胞质中的黑点),表明三价铁储存在铁蛋白笼中,而NFE2L2/NRF2 KO 细胞在柠檬酸铁铵 (FAC) 处理后 Perls 染色非常有限FAC 处理,尽管这些细胞含有许多与 LC3 共定位的铁蛋白聚集体( Fig. 3K ),表明脱铁铁蛋白被招募到NFE2L2/NRF2 KO 细胞的自噬体中。这一结果表明,过量的 NCOA4 导致脱铁铁蛋白在铁掺入铁蛋白复合物之前快速招募到自噬体中。接下来,测试了 siRNA 介导的NCOA4敲低对缓解NFE2L2/NRF2 KO 细胞中观察到的 LIP 增加和铁死亡的影响。 NCOA4 -siRNA对WT和KO细胞系中FTH1/FTL(增加)和LC3-I/LC3-II(减少)的蛋白质水平有轻微影响(图S4D)。 NCOA4的敲低减轻了 IKE 处理的NFE2L2/NRF2 KO 细胞中 4-HNE 加合蛋白的形成(图 S4、D 和 E)。 NFE2L2/NRF2 KO 细胞中NCOA4敲低所提供的保护还通过 FTH1 斑点形成的减少、Fe 2+敏感性铁橙荧光强度的降低以及经历铁死亡的细胞减少来显现(图 S4F)。与这些结果一致, NCOA4敲低显着增强了 IKE 处理下NFE2L2/NRF2 KO 细胞的存活率(图 S4G)。此外,与 WT 相比, NFE2L2/NRF2 KO 细胞中铁转运蛋白 ( SLC40A1 ) 的 mRNA 水平显着较高(图 S4H),这表明在NFE2L2/NRF2 KO 细胞中观察到的游离不稳定铁的积累很可能不是由于铁转运蛋白表达的变化,尽管之前有报道( 53 )。

Table 2. Mander’s and Pearson’s coefficients for ferritin (FTH1/FTL) colocalization with autophagosome (LC3) versus lysosome (LAMP1).

表 2. 铁蛋白 (FTH1/FTL) 与自噬体 (LC3) 与溶酶体 (LAMP1) 共定位的 Mander 和 Pearson 系数。

| Mander’s coefficient 曼德系数 | Pearson’s coefficient 皮尔逊系数 | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| LC3/FTH1 | FTH1/LC3 光纤到户1/LC3 | ||

| NRF2 WT NRF2野生型 | 0.466 | 0.356 | r = 0.696 r = 0.696 |

| NRF2 KO-1 | 0.543 | 0.684 | r = 0.825 r = 0.825 |

| NRF2 KO-2 | 0.516 | 0.678 | r = 0.819 r = 0.819 |

| LAMP1/FTH1 灯1/FTH1 | FTH1/LAMP1 FTH1/灯1 | ||

| NRF2 WT NRF2野生型 | 0.336 | 0.426 | r = 0.701 r = 0.701 |

| NRF2 KO-1 | 0.187 | 0.325 | r = 0.305 r = 0.305 |

| NRF2 KO-2 | 0.195 | 0.321 | r = 0.225 r = 0.225 |

| LC3/FTL | FTL/LC3 超光速/LC3 | ||

| NRF2 WT NRF2野生型 | 0.358 | 0.222 | r = 0.676 r = 0.676 |

| NRF2 KO-1 | 0.695 | 0.725 | r = 0.850 r = 0.850 |

| NRF2 KO-2 | 0.622 | 0.756 | r = 0.785 r = 0.785 |

| LAMP1/FTL 灯1/FTL | FTL/ LAMP1 超光速/灯1 | ||

| NRF2 WT NRF2野生型 | 0.329 | 0.252 | r = 0.621 r = 0.621 |

| NRF2 KO-1 | 0.185 | 0.318 | r = 0.252 r = 0.252 |

| NRF2 KO-2 | 0.105 | 0.345 | r = 0.325 r = 0.325 |

NRF2 regulates iron homeostasis through HERC2, VAMP8, and NCOA4

NRF2 通过 HERC2、VAMP8 和 NCOA4 调节铁稳态

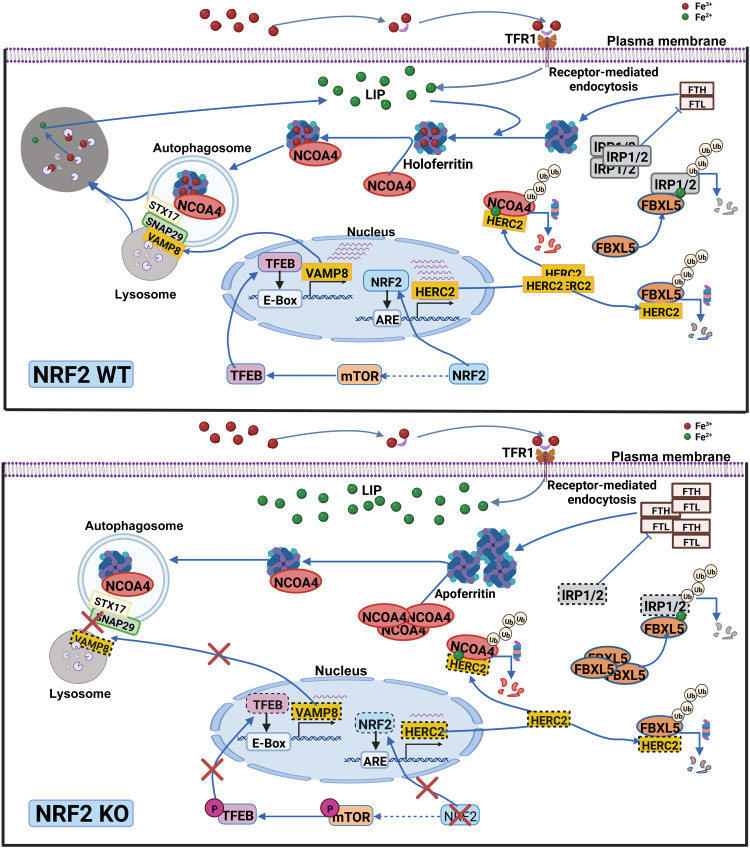

Collectively, our results have revealed a previously undiscovered function of NRF2, i.e., NRF2 regulates iron homeostasis and ferroptosis through HERC2, VAMP8, and NCOA4 (illustration in Fig. 4). By controlling their protein levels, NRF2 regulates both ferritin synthesis and degradation. First, HERC2, an E3 ubiquitin ligase for FBXL5 and NCOA4, is an NRF2 target gene; deletion of NRF2 results in reduced HERC2 expression, increased stability of FBXL5 and NCOA4, decreased IRP2 protein stability, and enhanced FTH synthesis. Second, NRF2 indirectly controls VAMP8 through the mTOR-TFEB axis. In NFE2L2/NRF2 KO cells, decreased TFEB-dependent transcription of VAMP8 results in blockage of autophagosome-lysosome fusion and inhibition of ferritinophagy. Third, excessive accumulation of NCOA4 in NFE2L2/NRF2 KO cells causes recruitment of apoferritin into autophagosomes, leading to autophagosomal accumulation of apoferritin/NCOA4, increased LIP, and enhanced sensitivity to ferroptotic cell death.

总的来说,我们的结果揭示了 NRF2 以前未被发现的功能,即 NRF2 通过 HERC2、VAMP8 和 NCOA4 调节铁稳态和铁死亡(图 1) Fig. 4 )。通过控制蛋白质水平,NRF2 调节铁蛋白的合成和降解。首先, HERC2是FBXL5和NCOA4的E3泛素连接酶,是NRF2靶基因; NRF2 的缺失导致 HERC2 表达减少,FBXL5 和 NCOA4 稳定性增加,IRP2 蛋白稳定性降低,FTH 合成增强。其次,NRF2通过mTOR-TFEB轴间接控制VAMP8 。在NFE2L2/NRF2 KO 细胞中, VAMP8的 TFEB 依赖性转录减少导致自噬体-溶酶体融合受阻并抑制铁蛋白自噬。第三, NFE2L2/NRF2 KO细胞中NCOA4的过度积累导致脱铁铁蛋白募集到自噬体中,导致脱铁铁蛋白/NCOA4在自噬体中积累,LIP增加,并增强对铁死亡细胞死亡的敏感性。

Fig. 4. NRF2 regulates iron homeostasis through HERC2, VAMP8, and NCOA4.

图 4.NRF2 通过 HERC2、VAMP8 和 NCOA4 调节铁稳态。

NRF2 regulates iron homeostasis by controlling both ferritin synthesis and degradation. First, HERC2, an E3 ubiquitin ligase for FBXL5 and NCOA4, is an NRF2 target gene; deletion of NFE2L2/NRF2 results in reduced HERC2 expression, increased stability of FBXL5 and NCOA4, decreased IRP2 protein stability, and enhanced FTH synthesis. Second, NRF2 indirectly controls VAMP8 through the mTOR-TFEB axis. In NFE2L2/NRF2 KO cells, decreased TFEB-dependent transcription of VAMP8 results in blockage of autophagosome-lysosome fusion and inhibition of ferritinophagy. Third, excessive accumulation of NCOA4 in NFE2L2/NRF2 KO cells causes recruitment of apoferritin into autophagosomes, leading to autophagosomal accumulation of apoferritin/NCOA4, increased LIP, and enhanced sensitivity to ferroptotic cell death. Green dot, ferrous iron; red dot, ferric iron.

NRF2 通过控制铁蛋白合成和降解来调节铁稳态。首先, HERC2是FBXL5和NCOA4的E3泛素连接酶,是NRF2靶基因; NFE2L2/NRF2的缺失导致HERC2表达减少,FBXL5 和 NCOA4 稳定性增加,IRP2 蛋白稳定性降低,FTH 合成增强。其次,NRF2通过mTOR-TFEB轴间接控制VAMP8 。在NFE2L2/NRF2 KO 细胞中, VAMP8的 TFEB 依赖性转录减少导致自噬体-溶酶体融合受阻并抑制铁蛋白自噬。第三, NFE2L2/NRF2 KO细胞中NCOA4的过度积累导致脱铁铁蛋白募集到自噬体中,导致脱铁铁蛋白/NCOA4在自噬体中积累,LIP增加,并增强对铁死亡细胞死亡的敏感性。绿点,亚铁;红点,三价铁。

Contribution of the NRF2-HERC2 and NRF2-VAMP8/NCOA4 axes in controlling iron homeostasis and dictating ferroptosis sensitivity

NRF2-HERC2 和 NRF2-VAMP8/NCOA4 轴在控制铁稳态和决定铁死亡敏感性中的贡献

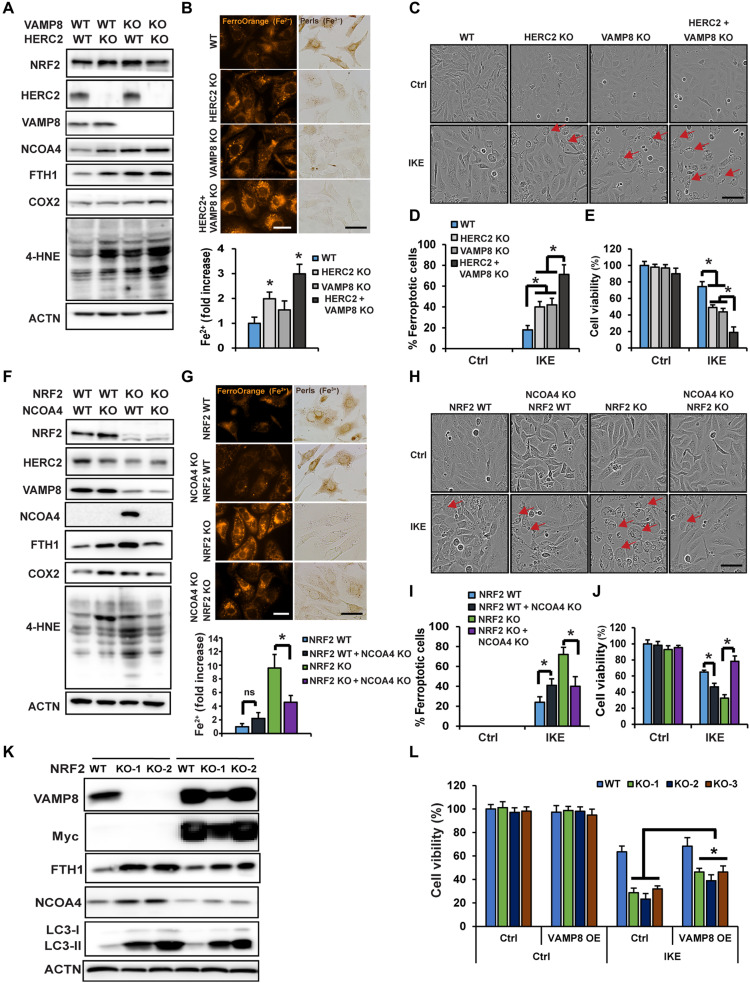

To further validate the contribution of the newly identified function of NRF2 in iron homeostasis, and to ensure the anti-ferroptotic function of NRF2 extends beyond just its mediation of redox balance, HERC2 and VAMP8 single or double KO cells were generated. Like what was observed in NFE2L2/NRF2 KO cells, KO of HERC2 or VAMP8 resulted in increased protein levels of FTH1 and NCOA4, as well as the ferroptosis markers COX2 and 4-HNE, with double- KO of HERC2/VAMP8 exhibiting a more pronounced phenotype than single KO (Fig. 5A). Also, KO of HERC2 or double KO significantly increased free iron levels as measured by both FerroOrange (Fig. 5B, FerroOrange panel) and Ferene-S colorimetric assay (Fig. 5B, bar graph, bottom), but decreased ferric iron–loaded ferritin cages (Fig. 5B, Perls staining). Consistently, KO enhanced ferroptotic cell death (Fig. 5, C and D) and reduced cell survival (Fig. 5E). The percentage of ferroptotic cells was ~20% in IKE-treated WT cells versus ~75% in the HERC2/VAMP8 double KO cells (Fig. 5D), with an ~30% decrease in cell viability in NFE2L2/NRF2 WT compared to an ~80% decrease in HERC2/VAMP8 double KO cells at 24 hours (Fig. 5E). A comparison of the percentage of ferroptotic cells in NFE2L2/NRF2 WT and the different KO cell lines following IKE treatment shows that cells with double KO of HERC2/VAMP8 exhibit an equivalent ferroptosis sensitivity as NFE2L2/NRF2 KO cells (Table 1). These results demonstrated that HERC2/VAMP8 double KO cells behaved like NFE2L2/NRF2 KO cells, as indicated by a similar accumulation of apoferritin/NCOA4, increased LIP, enhanced ferroptosis markers (COX2 and 4-HNE), and increased sensitivity to ferroptotic cell death.

为了进一步验证新发现的 NRF2 功能在铁稳态中的贡献,并确保 NRF2 的抗铁死亡功能超出其介导氧化还原平衡的范围,生成了HERC2和VAMP8单或双 KO 细胞。与在NFE2L2/NRF2 KO 细胞中观察到的情况一样, HERC2或VAMP8的 KO 导致 FTH1 和 NCOA4 以及铁死亡标记物 COX2 和 4-HNE 的蛋白水平增加,其中HERC2 / VAMP8的双 KO 表现出更明显的表型比单一 KO ( Fig. 5A )。此外,通过 FerroOrange 测量, HERC2的 KO 或双重 KO 显着增加了游离铁水平( Fig. 5B ,FerroOrange 面板)和 Ferene-S 比色测定( Fig. 5B ,条形图,底部),但铁蛋白笼中的三价铁含量减少( Fig. 5B ,Perls 染色)。一致地,KO 增强了铁死亡细胞死亡( Fig. 5, C and D )和细胞存活率降低( Fig. 5E )。 IKE 处理的 WT 细胞中铁死亡细胞的百分比约为 20%,而HERC2 / VAMP8双 KO 细胞中的铁死亡细胞百分比约为 75%( Fig. 5D ),24 小时时, NFE2L2/NRF2 WT 细胞活力下降约 30%,而HERC2 / VAMP8双 KO 细胞活力下降约 80%( Fig. 5E )。对 IKE 处理后NFE2L2/NRF2 WT 和不同 KO 细胞系中铁死亡细胞的百分比进行比较,结果显示, HERC2 / VAMP8双 KO 的细胞表现出与NFE2L2/NRF2 KO 细胞相当的铁死亡敏感性。 Table 1 )。 这些结果表明, HERC2 / VAMP8双 KO 细胞的行为与NFE2L2/NRF2 KO 细胞相似,脱铁铁蛋白/NCOA4 的相似积累、LIP 增加、铁死亡标记物(COX2 和 4-HNE)增强以及对铁死亡细胞死亡的敏感性增加表明了这一点。 。

Fig. 5. Contribution of the NRF2-HERC2 and NRF2-VAMP8/NCOA4 axes in controlling iron homeostasis and dictating ferroptosis sensitivity.

图 5. NRF2-HERC2 和 NRF2-VAMP8/NCOA4 轴在控制铁稳态和指示铁死亡敏感性中的贡献。

HERC2 and VAMP8 single or double KO cells were established. (A) Status of HERC2/VAMP8 KO was determined by immunoblot analysis, along with the levels of the other indicated proteins. (B) These four cell lines were used to measure free iron using FerroOrange (upper left) and Ferene-S colorimetic assay (bottom), or ferric iron–ferritin cages by Perls staining after FAC treatment (100 μM, 12 hours) (upper right). Scale bars, 25 μm. (C) These four cell lines were left untreated or treated with IKE (10 μM), and cell growth was monitored using the IncuCyte imaging system. Results shown here were at 24 hours after treatment of IKE. Scale bar, 50 μm. (D) Percentage of ferroptotic cells from (C). (E) Cell viability measured by MTT assay. (F and G) Pooled NCOA4 KO cells in the NFE2L2/NRF2 WT or KO background were established and (F) the levels of the indicated proteins were determined by immunoblot analysis, and (G) free iron was measured using FerroOrange (upper left) or Ferene-S (bottom), or ferric iron–ferritin cages by Perls staining after FAC treatment (100 μM, 12 hours) (upper right). Scale bars, 25 μm. (H) These four cell lines were left untreated or treated with IKE (10 μM), and cell growth was monitored using the IncuCyte imaging system. Images shown were at 24 hours after treatment with IKE. Scale bar, 50 μm. (I) Percentage of ferroptotic cells from (H). *P < 0.05, n = 3. (J) Cell viability measured by MTT assay. *P < 0.05, n = 3. (K) FTH1, NCOA4, and LC3-I/II protein levels in NFE2L2/NRF2 WT or KO cells overexpressing VAMP8 were determined by immunoblot analysis. (L) Cell viability measured by MTT assay.

建立HERC2和VAMP8单或双KO细胞。 ( A ) 通过免疫印迹分析确定HERC2 / VAMP8 KO 的状态以及其他所示蛋白质的水平。 ( B ) 这四种细胞系用于使用 FerroOrange(左上)和 Ferene-S 比色测定(下)测量游离铁,或在 FAC 处理(100 μM,12 小时)后通过 Perls 染色测量三价铁-铁蛋白笼(上)正确的)。比例尺,25 μm。 ( C ) 这四种细胞系未经处理或用 IKE (10 μM) 处理,并使用 IncuCyte 成像系统监测细胞生长。这里显示的结果是 IKE 治疗后 24 小时的结果。比例尺,50 μm。 ( D ) (C) 中铁死亡细胞的百分比。 ( E )通过MTT测定测量细胞活力。 ( F和G ) 建立NFE2L2/NRF2 WT 或 KO 背景中的混合 NCOA4 KO 细胞,(F) 通过免疫印迹分析测定所示蛋白质的水平,(G) 使用 FerroOrange 测量游离铁(左上)或 Ferene-S(下),或 FAC 处理(100 μM,12 小时)后通过 Perls 染色的三价铁-铁蛋白笼(右上)。比例尺,25 μm。 ( H ) 这四种细胞系未经处理或用 IKE (10 μM) 处理,并使用 IncuCyte 成像系统监测细胞生长。显示的图像是 IKE 治疗后 24 小时的图像。比例尺,50 μm。 ( I )来自(H)的铁死亡细胞的百分比。 * P < 0.05, n = 3。 ( J ) 通过 MTT 测定测量细胞活力。 * P < 0。05, n = 3。( K )通过免疫印迹分析测定过表达VAMP8 的NFE2L2/NRF2 WT 或 KO 细胞中的 FTH1、NCOA4 和 LC3-I/II 蛋白水平。 ( L )通过MTT测定测量细胞活力。

As shown in our model (Fig. 4), NFE2L2/NRF2 KO cells exhibit excessive accumulation of NCOA4, which is a critical factor in mediating the recruitment of apoferritin into autophagosomes, leading to the observed increase in the LIP and enhanced sensitivity to ferroptotic cell death. To fully confirm this mechanism, and also validate the NCOA4 siRNA knockdown results presented in fig. S4 (D to G), CRISPR NCOA4 KO NFE2L2/NRF2 WT and NFE2L2/NRF2 KO cell lines were generated. NCOA4 KO in NFE2L2/NRF2 WT cells enhanced ferroptosis as indicated by increased COX2 and 4-HNE (Fig. 5F), which was accompanied by increased ferroptosis and decreased survival (Fig. 5, H, I, and J). A marked contrast was observed when NCOA4 was knocked out in NFE2L2/NRF2 KO cells, as NCOA4 deletion reduced FTH1 protein levels, reduced ferroptosis markers COX2 and 4-HNE (Fig. 5F), decreased LIP as measured by both FerroOrange (Fig. 5G, FerroOrange panel) and Ferene-S colorimetic assay (Fig. 5G, bar graph, bottom), increased ferric iron–loaded ferritin cages (Fig. 5G, Perls staining), decreased percentage of ferroptotic cells (Fig. 5, H and I), and restored NFE2L2/NRF2 KO cell survival following IKE treatment to that of NFE2L2/NRF2 WT cells (Fig. 5J). In addition, overexpression of VAMP8 in NFE2L2/NRF2 KO SKOV3 cells alleviated autophagy blockage, as indicated by reduced protein levels of FTH1, NCOA4, and LC3-I/II (Fig. 5K), as well as reduced ferroptosis sensitivity in IKE-treated NFE2L2/NRF2 KO but not NFE2L2/NRF2 WT cells (Fig. 5L). Together, these results demonstrate the significance of NRF2-mediated iron sensing, by controlling ferritin synthesis/degradation, in determining a cancer cell’s response to ferroptosis inducers.

如我们的模型所示( Fig. 4 ), NFE2L2/NRF2 KO细胞表现出NCOA4的过度积累,这是介导脱铁铁蛋白募集到自噬体中的关键因素,导致观察到的LIP增加和对铁死亡细胞死亡的敏感性增强。为了充分证实这一机制,并验证图 1 所示的NCOA4 siRNA 敲低结果。生成了 S4(D 至 G)、CRISPR NCOA4 KO NFE2L2/NRF2 WT 和NFE2L2/NRF2 KO 细胞系。 COX2 和 4-HNE 增加表明NFE2L2/NRF2 WT 细胞中的NCOA4 KO 增强了铁死亡( Fig. 5F ),伴随着铁死亡增加和存活率下降( Fig. 5, H, I, and J )。当在NFE2L2/NRF2 KO 细胞中敲除NCOA4时,观察到显着的对比,因为NCOA4缺失降低了 FTH1 蛋白水平,降低了铁死亡标记物 COX2 和 4-HNE( Fig. 5F ),通过 FerroOrange 测量,LIP 降低( Fig. 5G ,FerroOrange 面板)和 Ferene-S 比色测定( Fig. 5G ,条形图,底部),增加三价铁负载铁蛋白笼( Fig. 5G ,Perls 染色),铁死亡细胞百分比下降( Fig. 5, H and I ),并将 IKE 处理后的NFE2L2/NRF2 KO 细胞存活率恢复至NFE2L2/NRF2 WT 细胞的存活率( Fig. 5J )。此外, NFE2L2/NRF2 KO SKOV3 细胞中VAMP8的过表达减轻了自噬阻断,FTH1、NCOA4 和 LC3-I/II 的蛋白水平降低表明了这一点。 Fig. 5K ),以及 IKE 处理的NFE2L2 / NRF2 KO 细胞中铁死亡敏感性降低,但NFE2L2 / NRF2 WT 细胞没有降低( Fig. 5L )。 总之,这些结果证明了 NRF2 介导的铁感应通过控制铁蛋白合成/降解在确定癌细胞对铁死亡诱导剂的反应中的重要性。

NRF2 expression correlates with HERC2 and VAMP8 levels in human cancer tissues, as well as ferroptosis resistance of cancer cell lines

NRF2 表达与人类癌症组织中的 HERC2 和 VAMP8 水平以及癌细胞系的铁死亡抗性相关

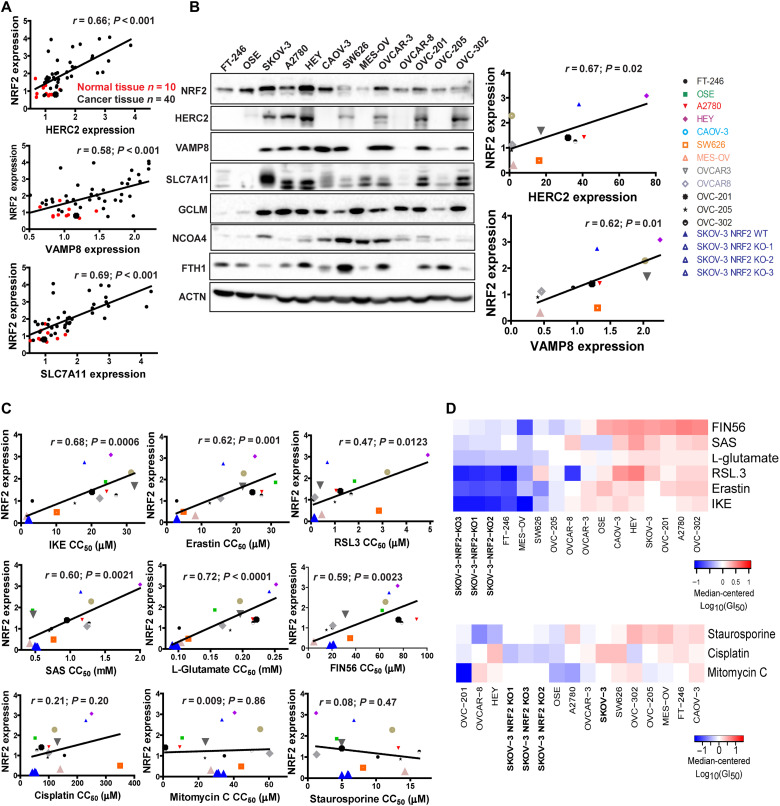

The translational relevance of this study was evaluated using human ovarian patient tissues to test whether there is a correlation between the expression of HERC2, VAMP8, and NRF2. NRF2 protein levels correlated strongly with HERC2 and VAMP8 (SLC7A11, a known NRF2 target gene, was used as a positive control) (Fig. 6A and fig. S5A). Notably, NRF2 expression was low in normal tissues but up-regulated in tumors (Fig. 6A, red versus black dots). Similarly, there was a positive correlation between NRF2 and HERC2, as well as NRF2 and VAMP8 across a wide variety of different ovarian cancer cell lines (Fig. 6B). Normal ovarian cell lines FT-246 and OSE were excluded in the correlation curve because of the low levels of HERC2 and VAMP8 (Fig. 6B). In support of our model, most cancer cell lines showed a negative correlation between the levels of NRF2 and either FTH1 or NCOA4 (Fig. 6B). Next, the response of these cell lines to ferroptosis and other mode of cell death inducers was measured (fig. S5B) and the 50% growth inhibition concentration (GI50) for each individual compound was calculated (Table 3). As expected, a positive correlation between NRF2 expression and GI50 values of the different ferroptosis inducers among these cell lines was observed (Fig. 6C, top two rows). In contrast, there was no correlation between NRF2 and GI50 values of the other cytotoxic compounds that do not induce ferroptosis, including chemotherapeutic drugs (cisplatin and mitomycin C) and the apoptosis inducer staurosporine (Fig. 6C, bottom row). The finding that NRF2 determines the resistance of ovarian cancer cell lines to ferroptosis inducers was further illustrated in a heatmap indicating the GI50 profiles of these cell lines in response to ferroptotic inducers, as the three NFE2L2/NRF2 KO SKOV-3 cell lines were clustered as the most sensitive to all ferroptotic inducers, far apart from WT SKOV-3 (Fig. 6D, top). In contrast, the sensitivity of the three NFE2L2/NRF2 KO SKOV-3 cell lines to other compounds in relation to the other cell lines tested was only increased slightly (Fig. 6D, bottom).

本研究的翻译相关性使用人类卵巢患者组织进行评估,以测试 HERC2、VAMP8 和 NRF2 的表达之间是否存在相关性。 NRF2 蛋白水平与 HERC2 和 VAMP8 密切相关(已知 NRF2 靶基因 SLC7A11 用作阳性对照)( Fig. 6A 和图。 S5A)。值得注意的是,NRF2 表达在正常组织中较低,但在肿瘤中表达上调。 Fig. 6A ,红点与黑点)。同样,在多种不同的卵巢癌细胞系中,NRF2 和 HERC2 以及 NRF2 和 VAMP8 之间存在正相关性。 Fig. 6B )。由于 HERC2 和 VAMP8 水平较低,正常卵巢细胞系 FT-246 和 OSE 被排除在相关曲线中( Fig. 6B )。为了支持我们的模型,大多数癌细胞系显示 NRF2 水平与 FTH1 或 NCOA4 水平呈负相关( Fig. 6B )。接下来,测量这些细胞系对铁死亡和其他细胞死亡诱导剂模式的反应(图 S5B),并计算每种化合物的 50% 生长抑制浓度(GI 50 )( Table 3 )。正如预期的那样,在这些细胞系中观察到 NRF2 表达与不同铁死亡诱导剂的 GI 50值呈正相关( Fig. 6C ,前两行)。相比之下,其他不诱导铁死亡的细胞毒性化合物的 NRF2 和 GI 50值之间没有相关性,包括化疗药物(顺铂和丝裂霉素 C)和凋亡诱导剂星形孢菌素(staurosporine)。 Fig. 6C ,底行)。 NRF2 决定卵巢癌细胞系对铁死亡诱导剂的抗性这一发现在热图中得到了进一步说明,该热图显示了这些细胞系响应铁死亡诱导剂的 GI 50概况,因为三个NFE2L2/NRF2 KO SKOV-3 细胞系聚集在一起与 WT SKOV-3 相比,它是对所有铁死亡诱导剂最敏感的( Fig. 6D , 顶部)。相比之下,与测试的其他细胞系相比,三种NFE2L2/NRF2 KO SKOV-3 细胞系对其他化合物的敏感性仅略有增加( Fig. 6D , 底部)。

Fig. 6. NRF2 expression correlates with HERC2 and VAMP8 levels in human cancer tissues, as well as ferroptosis resistance.

图 6. NRF2 表达与人类癌症组织中的 HERC2 和 VAMP8 水平以及铁死亡抗性相关。

(A) Correlation between NRF2 expression and HERC2 or VAMP8 levels in human ovarian tissues was determined by immunohistochemistry analysis. HERC2, VAMP8, and SLC7A11 expression were imaged (see fig. S4A), and average intensity was measured and plotted against NRF2. Normal tissue (n = 10) plotted as red dots; cancer tissue (n = 40) plotted as black dots. (B) NRF2 and ferroptosis-related protein levels in various ovarian cancer cell lines were measured by immunoblot analysis (left). The expression of HERC2, VAMP8, and SLC7A11 was quantified and plotted against NRF2 in each cell line (right). (C) Correlation between NRF2 expression and the GI50 of ferroptosis-inducing compounds (IKE, erastin, RSL3, SAS, l-glutamate, and FIN56) and apoptosis-inducing compounds (cisplatin, mitomycin C, or staurosporine). Each cell line was treated with eight doses of the indicated compound for 24 hours, and cell viability was measured by MTT assay. GI50 values were calculated by log-logistic fitting (Table 3). (D) Heatmap GI50 profiles were created using median-centered z-score analysis of the GI50 values.

( A )通过免疫组织化学分析确定人卵巢组织中NRF2表达与HERC2或VAMP8水平之间的相关性。对 HERC2、VAMP8 和 SLC7A11 表达进行成像(参见图 S4A),测量平均强度并针对 NRF2 进行绘图。正常组织 ( n = 10) 绘制为红点;癌组织( n = 40)绘制为黑点。 ( B ) 通过免疫印迹分析测量各种卵巢癌细胞系中的 NRF2 和铁死亡相关蛋白水平(左)。对每个细胞系中 HERC2、VAMP8 和 SLC7A11 的表达进行定量并相对于 NRF2 进行绘图(右)。 ( C ) NRF2 表达与铁死亡诱导化合物(IKE、erastin、RSL3、SAS、 l-谷氨酸和 FIN56)和细胞凋亡诱导化合物(顺铂、丝裂霉素 C 或十字孢菌素)的 GI 50之间的相关性。每个细胞系用八个剂量的指定化合物处理 24 小时,并通过 MTT 测定测量细胞活力。 GI 50值通过对数逻辑拟合计算( Table 3 )。 ( D ) 热图 GI 50轮廓是使用 GI 50值的中位数中心z分数分析创建的。

Table 3. The 50% growth inhibition concentration (GI50) for each individual compound.

表 3. 每种化合物的 50% 生长抑制浓度 (GI 50 )。

| Cell lines 细胞系 | IKE (μM) | Erastin (μM) 橡皮素 (μM) | RSL-3 (μM) | SAS (μM) |

l-Glutamate (μM) l-谷氨酸 (μM) |

FIN46 (μM) | Cisplatin (μM) 顺铂 (μM) | Staurosporine (μM) | Mitomycin C (μM) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HEY | 25.5 ± 0.48 25.5±0.48 | 225.32 ± 0.22 225.32±0.22 | 3.68 ± 0.09 3.68±0.09 | 2,000 ± 30.6 2,000±30.6 | 252,020 ± 117 | 75.25 ± 0.48 75.25±0.48 | 250 ± 1.93 250±1.93 | 2.22 ± 0.29 | 40.51 ± 0.40 |

| SKOV-3 | 18 ± 0.16 18±0.16 | 16.23 ± 0.16 16.23±0.16 | 1.85 ± 0.01 1.85±0.01 | 1,250 ± 9.73 | 241,300 ± 62.9 | 68 ± 0.16 68±0.16 | 230 ± 1.92 230±1.92 | 6.75 ± 0.59 | 33.29 ± 0.33 |

| CAOV-3 | 31.25 ± 0.20 31.25±0.20 | 22.1 ± 0.02 22.1±0.02 | 3.2 ± 0.25 3.2±0.25 | 1,300 ± 10.64 1,300±10.64 | 195,690 ± 97.7 | 65.02 ± 0.21 65.02±0.21 | 120 ± 3.21 120±3.21 | 12.35 ± 0.99 | 55.01 ± 1.60 |

| OSE | 24 ± 0.31 24±0.31 | 31.25 ± 0.31 31.25±0.31 | 1.48 ± 0.03 1.48±0.03 | 460 ± 8.70 460±8.70 | 156,700 ± 88.8 | 62.26 ± 1.71 62.26±1.71 | 52 ± 1.73 52±1.73 | 4.24 ± 0.13 | 10.8 ± 0.18 |

| OVCAR-3 | 28 ± 0.01 28±0.01 | 21.8 ± 0.01 21.8±0.01 | 0.98 ± 0.02 0.98±0.02 | 470 ± 20.1 470±20.1 | 196,150 ± 100 | 31.25 ± 0.19 31.25±0.19 | 130 ± 3.25 130±3.25 | 4.97 ± 0.54 | 23.96 ± 0.23 |

| A2780 | 24.3 ± 0.02 24.3±0.02 | 27.3 ± 0.98 27.3±0.98 | 1.65 ± 0.07 1.65±0.07 | 1,170 ± 11.5 | 215,510 ± 136 | 91.25 ± 0.27 91.25±0.27 | 100 ± 1.52 100±1.52 | 13.25 ± 0.87 | 9.44 ± 0.45 |

| OVC-201 | 20.15 ± 0.02 20.15±0.02 | 24.6 ± 1.16 24.6±1.16 | 1.23 ± 0.09 1.23±0.09 | 952 ± 30.42 952±30.42 | 221,343 ± 157 | 75.96 ± 0.23 75.96±0.23 | 74 ± 1.55 74±1.55 | 4.99 ± 0.56 | 1.136 ± 0.09 |

| OVC-302 | 27 ± 0.97 27±0.97 | 27.2 ± 0.02 27.2±0.02 | 1.68 ± 0.09 1.68±0.09 | 1,270 ± 9.13 | 216,090 ± 142 | 78.7 ± 0.97 78.7±0.97 | 58 ± 0.98 58±0.98 | 16.32 ± 1.82 | 50.19 ± 0.98 |

| OVCAR-8 | 22.35 ± 0.02 22.35±0.02 | 15.5 ± 0.03 15.5±0.03 | 0.16 ± 0.03 0.16±0.03 | 1,240 ± 25.7 1,240±25.7 | 168,570 ± 71.2 | 20.71 ± 0.22 20.71±0.22 | 99 ± 2.01 99±2.01 | 1.3 ± 0.39 | 60.32 ± 1.05 |

| FT-246 | 3.2 ± 0.03 3.2±0.03 | 2.86 ± 0.06 2.86±0.06 | 0.112 ± 0.02 0.112±0.02 | 730 ± 24.3 730±24.3 | 101,300 ± 106 | 20.35 ± 0.35 20.35±0.35 | 155 ± 4.41 155±4.41 | 10.25 ± 0.82 | 34.7 ± 0.88 |

| OVC-205 | 15.26 ± 0.11 15.26±0.11 | 12.36 ± 0.30 12.36±0.30 | 1 ± 0.04 1±0.04 | 700 ± 13.6 700±13.6 | 180,700 ± 103 | 15.25 ± 0.11 15.25±0.11 | 96 ± 1.73 96±1.73 | 13.57 ± 0.67 | 23.69 ± 0.48 |

| SW626 | 10.15 ± 1.09 10.15±1.09 | 4.85 ± 0.02 4.85±0.02 | 1.65 ± 0.25 1.65±0.25 | 760 ± 17.5 760±17.5 | 115,610 ± 157 | 20 ± 1.09 20±1.09 | 240 ± 4.68 240±4.68 | 8.09 ± 0.37 | 44.25 ± 0.78 |

| MES-OV | 1.6 ± 0.04 1.6±0.04 | 8.21 ± 0.03 8.21±0.03 | 0.45 ± 0.05 0.45±0.05 | 420 ± 25.2 420±25.2 | 103,960 ± 44.4 | 4.65 ± 0.42 4.65±0.42 | 140 ± 2.51 140±2.51 | 14.21 ± 0.51 | 27.04 ± 0.27 |

| SKOV-3 NRF2 KO-1 | 2.01 ± 0.03 2.01±0.03 | 2.8 ± 0.05 2.8±0.05 | 0.15 ± 0.03 0.15±0.03 | 521 ± 4.87 521±4.87 | 95,052 ± 31.9 | 20.56 ± 0.31 20.56±0.31 | 42 ± 0.21 42±0.21 | 5.99 ± 0.16 | 30.25 ± 0.17 |

| SKOV-3 NRF2 KO-2 | 2.32 ± 0.01 2.32±0.01 | 3.01 ± 0.04 3.01±0.04 | 0.16 ± 0.02 0.16±0.02 | 533 ± 5.63 533±5.63 | 98,665 ± 70.2 | 18.22 ± 0.18 18.22±0.18 | 45 ± 0.63 45±0.63 | 4.99 ± 0.26 | 34.25 ± 0.10 |

| SKOV-3 NRF2 KO-3 | 2.11 ± 0.03 2.11±0.03 | 2.95 ± 0.03 2.95±0.03 | 0.13 ± 0.04 0.13±0.04 | 495 ± 9.33 495±9.33 | 90,355 ± 42.5 | 21.25 ± 0.32 21.25±0.32 | 51 ± 0.5 51±0.5 | 5.86 ± 0.44 | 31.25 ± 0.16 |

Genetic or pharmacological NRF2 inhibition enhanced sensitivity to ferroptotic cell death in preclinical models

遗传或药理学 NRF2 抑制增强临床前模型中对铁死亡细胞死亡的敏感性

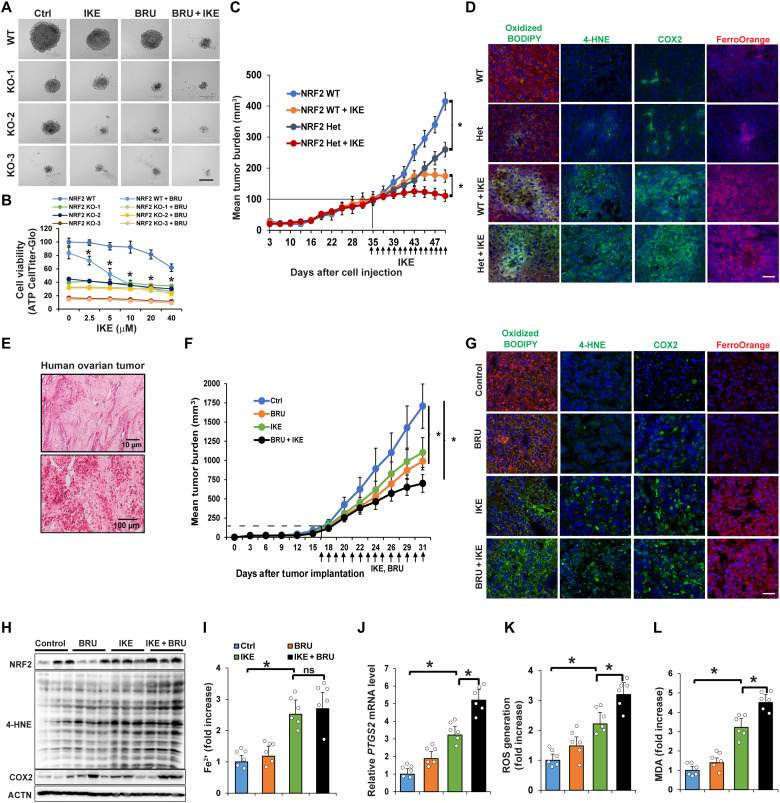

The results shown in Fig. 6 (C and D) indicated that NRF2 effectively protected ovarian cancer cells from ferroptosis-inducing compounds; thus, the idea of killing cancer cells using a combined treatment of an NRF2 inhibitor and ferroptosis inducer was explored using three preclinical models. (i) Three-dimensional (3D) tumor spheroids: In NFE2L2/NRF2-WT SKOV-3 cells, IKE resulted in a dose-dependent decrease in tumor spheroid size and cell viability, both of which were further decreased by adding BRU, an NRF2 inhibitor (24-hour IKE treatment data; Fig. 7, A and B). However, the same number of NFE2L2/NRF2-KO SKOV-3 cells formed much smaller spheroids with a lower baseline viability even in the absence of IKE treatment. Similar results were obtained using two other ovarian cancer cell lines (OVCAR-8 and OVC-201) (fig. S6A). (ii) NFE2L2/NRF2 WT and heterozygous SKOV-3 xenografts: NFE2L2/NRF2 WT xenografts implanted in NSG (nonobese diabetic severe combined immunodeficient gamma) mice grew quickly, and tumor growth was significantly inhibited by treatment with IKE (Fig. 7C). The NFE2L2/NRF2 heterozygous tumor growth curve before the tumor size reached 100 to 125 mm3 was the same as NFE2L2/NRF2 WT; however, the growth of NFE2L2/NRF2 heterozygous tumors after they reached 125 mm3 slowed as the tumor size increased. Moreover, NRF2 heterozygous tumor size was significantly smaller than NFE2L2/NRF2 WT tumor size after daily injection of IKE (40 mg/kg) for 14 days (Fig. 7C). No obvious weight changes in the treated mice were observed (fig. S6B). Furthermore, IKE-treated NFE2L2/NRF2 WT and heterozygous tumor tissues showed increased lipid droplet formation [arrowheads in hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) and Nile Red] and necrotic areas (arrows in H&E) (fig. S6C). WT and NFE2L2/NRF2 heterozygous tumors treated with IKE exhibited increased markers of ferroptosis, including C11-BODIPY581/591 staining, 4-HNE, COX2 (immunifluorescence and immunoblots), PTGS2 mRNA level), LIP (FerroOrange staining and Ferene-S assay), MDA, and ROS (Fig. 7D and fig. S6, D to H). Several ferroptosis markers, such as 4-HNE protein adduct formation, MDA production, and PTGS2 mRNA levels, were significantly higher in IKE-treated NFE2L2/NRF2 heterozygous than in IKE-treated WT tumors. (iii) Poorly differentiated ovarian carcinoma patient-derived xenografts (PDX): We established an ovarian PDX tumor model using second passage patient tissues implanted into an NSG mouse. Immunohistochemistry analysis of the patient tissue before implantation confirmed the clinical diagnosis that the case appeared to have originated from the ovary and was poorly differentiated (Fig. 7E). PDX tumor growth decreased significantly in the presence of BRU, IKE, or both in combination, with the dual treatment having the greatest effect (Fig. 7F). None of the treatment groups exhibited a significant decrease in mouse body weight (fig. S6I). Lipid droplet formation (H&E and Nile Red staining) was increased in both the IKE and IKE + BRU groups compared to BRU alone or control (fig. S6J). All specific ferroptosis markers measured, such as 4-HNE adduct formation, COX2/PTGS2, and MDA/ROS generation, were significantly increased in the presence of IKE + BRU compared to IKE alone (Fig. 7, G to L). Collectively, these results from three different preclinical models demonstrate the effectiveness of combined NRF2 inhibition and ferroptosis induction in treating cancer.

结果显示在 Fig. 6 (C and D) 表明 NRF2 有效保护卵巢癌细胞免受铁死亡诱导化合物的侵害;因此,我们使用三种临床前模型探索了使用 NRF2 抑制剂和铁死亡诱导剂联合治疗来杀死癌细胞的想法。 (i) 三维 (3D) 肿瘤球体:在NFE2L2/NRF2 -WT SKOV-3 细胞中,IKE 导致肿瘤球体大小和细胞活力呈剂量依赖性下降,通过添加 BRU(一种NRF2抑制剂(24小时IKE治疗数据; Fig. 7, A and B )。然而,即使在没有 IKE 处理的情况下,相同数量的NFE2L2/NRF2 -KO SKOV-3 细胞也会形成小得多的球体,具有较低的基线活力。使用另外两种卵巢癌细胞系(OVCAR-8 和 OVC-201)也获得了类似的结果(图 S6A)。 (ii)NFE2L2/NRF2 WT和杂合SKOV-3异种移植物:植入NSG(非肥胖糖尿病严重联合免疫缺陷γ)小鼠中的NFE2L2/NRF2 WT异种移植物生长迅速,并且通过IKE治疗显着抑制肿瘤生长。 Fig. 7C )。 NFE2L2/NRF2杂合体在肿瘤大小达到100~125mm 3之前的肿瘤生长曲线与NFE2L2/NRF2 WT相同;然而, NFE2L2/NRF2杂合肿瘤在达到125mm 3后,随着肿瘤尺寸的增加而生长减慢。此外,每天注射 IKE (40 mg/kg) 14 天后, NRF2杂合肿瘤大小显着小于NFE2L2/NRF2 WT 肿瘤大小( Fig. 7C )。没有观察到治疗小鼠的明显体重变化(图S6B)。 此外,IKE处理的NFE2L2/NRF2 WT和杂合肿瘤组织显示脂滴形成增加[苏木精和曙红(H&E)和尼罗红中的箭头]和坏死区域(H&E中的箭头)(图S6C)。用 IKE 处理的 WT 和NFE2L2/NRF2杂合肿瘤表现出铁死亡标志物增加,包括 C11-BODIPY 581/591染色、4-HNE、COX2(免疫荧光和免疫印迹)、 PTGS2 mRNA 水平)、LIP(FerroOrange 染色和 Ferene-S 测定) )、MDA 和 ROS ( Fig. 7D 和图。 S6、D 至 H)。几种铁死亡标志物,例如 4-HNE 蛋白加合物形成、MDA 产生和PTGS2 mRNA 水平,在 IKE 处理的NFE2L2/NRF2杂合子中显着高于 IKE 处理的 WT 肿瘤。 (iii)低分化卵巢癌患者来源的异种移植物(PDX):我们使用植入 NSG 小鼠的第二代患者组织建立了卵巢 PDX 肿瘤模型。植入前对患者组织进行的免疫组织化学分析证实了临床诊断,即该病例似乎起源于卵巢且低分化( Fig. 7E )。在 BRU、IKE 或两者联合存在的情况下,PDX 肿瘤生长显着下降,其中双重治疗效果最大( Fig. 7F )。没有一个治疗组表现出小鼠体重的显着下降(图S6I)。与单独 BRU 或对照组相比,IKE 和 IKE + BRU 组的脂滴形成(H&E 和尼罗红染色)均有所增加(图 S6J)。 与单独的 IKE 相比,在 IKE + BRU 存在的情况下,测量的所有特定铁死亡标记物,例如 4-HNE 加合物形成、COX2/ PTGS2和 MDA/ROS 生成均显着增加( Fig. 7, G to L )。总的来说,来自三种不同临床前模型的这些结果证明了联合 NRF2 抑制和铁死亡诱导在治疗癌症中的有效性。

Fig. 7. Genetic or pharmacological NRF2 inhibition enhanced sensitivity to ferroptotic cell death in preclinical models.

(A) NFE2L2/NRF2 WT or KO SKOV-3 cell lines were grown for 3 to 5 days until 3D sphere formation. Spheroids were treated with IKE (10 μM), BRU (20 nM), or IKE + BRU for 24 hours. Scale bar, 50 μm. (B) Cell viability of NFE2L2/NRF2 WT and KO cell lines at 24-hour treatment assessed by CellTiter-Glo assay. *P < 0.05, n = 8. (C) NFE2L2/NRF2 WT or heterozygous (Het) SKOV-3 cells were subcutaneously injected; once tumors reached 100 mm3, mice were intraperitoneally injected with IKE (40 mg/kg) or vehicle control for 14 days. Tumor volume was measured and plotted as mean tumor burden (mm3). *P < 0.05, n = 15 per group. (D) Tumor tissues were probed with C11-BODIPY581/591, 4-HNE and COX2 antibodies, or FerroOrange. Scale bar, 50 μm. (E) H&E of human ovarian tissue (P0) used for the PDX model. (F) PDX tissue (P1) was implanted; once tumor size reached ~100 mm3, mice were intraperitoneally injected with vehicle, BRU (0.25 mg/kg), IKE (20 mg/kg), or IKE + BRU for 14 days. Tumor size was measured and plotted same as (C). *P < 0.05, n = 10 per group. (G) Tumor tissues were probed with C11-BODIPY581/591, 4-HNE and COX2 antibodies, or FerroOrange. Scale bar, 50 μm. (H) 4-HNE adduct and COX2 protein levels measured by immunoblot analysis. (I) LIP measured using Ferene-S. (J) PTGS2 mRNA levels measured by RT-PCR. (K) ROS levels measured by EPR spectroscopy. (L) MDA detected by TBARS assay. Data in (I) to (L) are represented as means ± SEM of tumor tissues from six individual mice (n = 6). *P < 0.05.

DISCUSSION

Cancer cells can thrive under high ROS conditions and excessive iron accumulation through metabolic reprogramming. Along these lines, many redox and iron regulatory signaling pathways have been shown to be altered, with cancer cells having developed an enhanced dependence on these changes (54). NRF2, one of several key players responsible for metabolic reprogramming, is up-regulated in many types of cancers to cope with the increased metabolic demands of the cancer cell (3, 20, 55). Since NRF2-addicted cancer cells have been shown to be highly resistant to classical chemotherapeutic drugs, we believe that enhancing toxic free iron accumulation to drive cancer cell death through ferroptosis would be the most effective way to kill these resistant cancer cells. However, there has been no effective and safe way to enhance the intracellular LIP, as iron administration would cause damage to normal organs or cells, as reported previously (56, 57). In this study, we have demonstrated that NRF2 inhibition can boost free iron accumulation and sensitize cancer cells and xenograft tumors to the ferroptosis inducer IKE. In contrast to feeding mice a high iron-containing diet that causes organ damage, NRF2 inhibition would selectively enhance free iron to toxic levels only in tumors with high NRF2 expression, and not in normal tissues. This creates an exploitable sensitivity of tumors to ferroptosis, thus providing a therapeutic window. The notion that specific NRF2 inhibition preferentially kills cancer cells without harming normal cells is also supported by these previous findings: First, the basal level of NRF2 in normal cells/tissues is low, whereas most cancer cells/tumors have higher levels of NRF2 to survive the stressful tumor microenvironment, which was also observed in the current study (Fig. 6, A and B). Second, NRF2 KO cells and mice grow and develop normally, indicating that NRF2 is not essential for normal cell growth or mouse development.

癌细胞可以在高活性氧条件和通过代谢重编程过度铁积累的情况下茁壮成长。沿着这些思路,许多氧化还原和铁调节信号通路已被证明发生了改变,癌细胞对这些变化的依赖性增强了。 54 )。 NRF2 是负责代谢重编程的几个关键参与者之一,在许多类型的癌症中都会上调,以应对癌细胞增加的代谢需求。 3 , 20 , 55 )。由于NRF2成瘾的癌细胞已被证明对经典化疗药物具有高度耐药性,因此我们相信,增强无毒铁积累以通过铁死亡驱动癌细胞死亡将是杀死这些耐药癌细胞的最有效方法。然而,目前还没有有效且安全的方法来增强细胞内 LIP,因为铁剂给药会对正常器官或细胞造成损害,正如之前报道的那样( 56 , 57 )。在这项研究中,我们证明了 NRF2 抑制可以促进游离铁积累并使癌细胞和异种移植肿瘤对铁死亡诱导剂 IKE 敏感。与给小鼠喂食导致器官损伤的高铁饮食相反,NRF2抑制只会选择性地将NRF2高表达的肿瘤中的游离铁提高到毒性水平,而不会在正常组织中。这创造了肿瘤对铁死亡的可利用敏感性,从而提供了治疗窗口。 先前的研究结果也支持了特异性 NRF2 抑制优先杀死癌细胞而不伤害正常细胞的观点:首先,正常细胞/组织中 NRF2 的基础水平较低,而大多数癌细胞/肿瘤具有较高水平的 NRF2 才能生存当前研究中也观察到了应激性肿瘤微环境( Fig. 6, A and B )。其次, NRF2 KO细胞和小鼠生长和发育正常,表明NRF2对于正常细胞生长或小鼠发育不是必需的。

Over the years, an increasing number of NRF2 target genes have been identified. NRF2 has been recognized to be crucial for promoting cancer cell survival by controlling cellular redox homeostasis (classical function), proteostasis, and metabolic stress (2–9). In this study, we discovered a signaling network through which NRF2 controls iron homeostasis through ferritin synthesis/degradation, thus dictating the intracellular LIP, and the sensitivity of cancer cells to ferroptotic cell death. Mechanistically, NRF2 regulates iron homeostasis via the following signaling pathways (Fig. 4): (i) NRF2-HERC2-FBXL5-IRP1/2–dependent ferritin synthesis, (ii) NRF2-TFEB-VAMP8–driven ferritinophagy for ferritin degradation, and (iii) NRF2-HERC2-NCOA4–mediated recruitment of ferritin to the autophagosome. Through these signaling axes, NFE2L2/NRF2 deletion disrupted ferritin metabolism through excessive ferritin synthesis and the accumulation of apoferritin-NCOA4 complexes in autophagosomes, leading to the massive toxic free iron accumulation that rendered NFE2L2/NRF2 KO cells more susceptible to ferroptotic cell death. It is worth emphasizing that our finding that NRF2 controls ferritin synthesis and degradation at the protein level is distinct from previous reports that NRF2 controls the mRNA levels of FTH1 and FTL. As shown in Fig. 2, the protein levels of FTH1 and FTL are higher in NRF2- KO cells (Fig. 2D), despite lower FTH1 and FTL mRNA levels (Fig. 2C), which may be due to the fact that the formation of the ferritin complex is primarily controlled by the UPS (HERC2, FBXL5, NCOA4, and IRP1/2), lysosomal degradation (FTH1, FTL, and NCOA4), and protein synthesis (FTH1 and FTL). Furthermore, we demonstrated the important contribution of this newly discovered NRF2-dependent regulation of iron metabolism in controlling cancer cell susceptibility to ferroptotic cell death, as double KO of HERC2 and VAMP8 in WT cells recapitulated the ferroptotic response observed in NFE2L2/NRF2 KO cells. In addition, while NCOA4 KO in NFE2L2/NRF2 WT enhanced ferroptosis, its KO in NFE2L2/NRF2 KO cells was protective. Furthermore, overexpression of VAMP8 in NFE2L2/NRF2 KO SKOV3 cells reduced their ferroptosis sensitivity, while it had no effect in WT cells. These results argue that NRF2-mediated ferritin metabolism and maintenance of iron homeostasis is critical in determining a cancer cell’s response to ferroptosis inducers.

多年来,越来越多的 NRF2 靶基因已被鉴定。 NRF2 已被认为通过控制细胞氧化还原稳态(经典功能)、蛋白质稳态和代谢应激,对于促进癌细胞存活至关重要。 2 – 9 )。在这项研究中,我们发现了一个信号网络,NRF2 通过铁蛋白合成/降解来控制铁稳态,从而决定细胞内 LIP 以及癌细胞对铁死亡细胞的敏感性。从机制上讲,NRF2 通过以下信号通路调节铁稳态( Fig. 4 ):(i)NRF2-HERC2-FBXL5-IRP1/2依赖的铁蛋白合成,(ii)NRF2-TFEB-VAMP8驱动的铁蛋白自噬导致铁蛋白降解,以及(iii)NRF2-HERC2-NCOA4介导的铁蛋白募集到自噬体。通过这些信号轴, NFE2L2/NRF2缺失通过过度铁蛋白合成和自噬体中脱铁铁蛋白-NCOA4 复合物的积累来破坏铁蛋白代谢,导致大量无毒铁积累,使NFE2L2/NRF2 KO 细胞更容易发生铁死亡。值得强调的是,我们发现NRF2在蛋白质水平上控制铁蛋白合成和降解,这与之前报道的NRF2控制FTH1和FTL的mRNA水平不同。 如图所示 Fig. 2 ,NRF2-KO 细胞中 FTH1 和 FTL 的蛋白水平较高( Fig. 2D ),尽管FTH1和FTL mRNA 水平较低( Fig. 2C ),这可能是由于铁蛋白复合物的形成主要由 UPS(HERC2、FBXL5、NCOA4 和 IRP1/2)、溶酶体降解(FTH1、FTL 和 NCOA4)和蛋白质合成控制( FTH1 和 FTL)。此外,我们证明了这种新发现的 NRF2 依赖性铁代谢调节在控制癌细胞对铁死亡细胞易感性方面的重要贡献,因为 WT 细胞中HERC2和VAMP8的双重 KO 重现了在NFE2L2/NRF2 KO 细胞中观察到的铁死亡反应。此外,虽然NFE2L2/NRF2 WT 中的NCOA4 KO 增强了铁死亡,但NFE2L2/NRF2 KO 细胞中的 NCOA4 KO 却具有保护作用。此外, VAMP8在NFE2L2/NRF2 KO SKOV3细胞中的过度表达降低了其铁死亡敏感性,而在WT细胞中则没有影响。这些结果表明,NRF2 介导的铁蛋白代谢和铁稳态的维持对于确定癌细胞对铁死亡诱导剂的反应至关重要。

It is important to note that the key is cellular localization/compartmentalization. The free LIP, as well as iron-loaded ferritin cages, is typically located in the cytosol. In normal cells, low iron leads to increased protein levels of NCOA4, which recruits ferritin to the autophagosome for autophagic degradation and release of free iron into the cytosol. In NRF2 KO cells, NRF2-dependent expression of HERC2, which degrades NCOA4, is low, resulting in constitutively higher levels of NCOA4 and recruitment of empty ferritin (apoferritin) to the autophagosome. This decoupling of NCOA4 degradation from the LIP, combined with blockage of autophagy flux (low VAMP8), results in ferritin sequestration away from labile iron in the cytosol, hence the observed increase in the LIP. It is also worth noting that this study is not merely claiming that NRF2 has anti-ferroptotic functions, which as mentioned above is already generally accepted because of the fact that several NRF2 target genes, including SLC7A11 (xCT) and GCLM, play a critical role in modulating intracellular GSH levels and thus GPX4 activity and sensitivity to inducers of ferroptosis. The important finding from this study is that the anti-ferroptosis function of NRF2 extends beyond its regulation of the antioxidant response, which is supported by our results (Fig. 5) showing the contribution of the NRF2-HERC2 and NRF2-VAMP8/NCOA4 axes to controlling iron homeostasis and dictating ferroptosis sensitivity. Another interesting observation is that the double-KO HERC2/VAMP8 cells behaved similarly to NFE2L2/NRF2 single KO cells, as evidenced by a similar accumulation of apoferritin/NCOA4, increased LIP, higher levels of ferroptosis markers (COX2 and 4-HNE adducts), and enhanced sensitivity to ferroptotic cell death. Although ferroptosis has been defined as both lipid peroxidation and iron dependent, whether lipid peroxidation, iron, or both are essential for ferroptosis induction is unclear. The fact that iron chelation can block ferroptosis induction argues that the accumulation of free iron alone is essential and sufficient to induce ferroptosis; however, it is hard to totally isolate the ferroptotic effect of labile iron from lipid peroxidation, since labile iron itself is redox active, the accumulation of which would be expected to lead to increased lipid peroxidation.

值得注意的是,关键是细胞定位/区室化。游离 LIP 以及载铁铁蛋白笼通常位于细胞质中。在正常细胞中,低铁会导致 NCOA4 蛋白水平升高,NCOA4 会将铁蛋白招募到自噬体中进行自噬降解,并将游离铁释放到细胞质中。在 NRF2 KO 细胞中,NRF2 依赖性的 HERC2 表达较低(可降解 NCOA4),导致 NCOA4 水平持续升高,并将空铁蛋白(脱铁铁蛋白)募集至自噬体。 NCOA4 降解与 LIP 的解耦,加上自噬流的阻断(低 VAMP8),导致铁蛋白与细胞质中的不稳定铁隔离,因此观察到 LIP 增加。还值得注意的是,这项研究不仅仅是声称NRF2具有抗铁死亡功能,如上所述,这一点已经被普遍接受,因为包括SLC7A11 (xCT)和GCLM在内的几个NRF2靶基因发挥着关键作用调节细胞内 GSH 水平,从而调节 GPX4 活性和对铁死亡诱导剂的敏感性。这项研究的重要发现是,NRF2 的抗铁死亡功能超出了其对抗氧化反应的调节范围,我们的结果支持了这一点( Fig. 5 ) 显示 NRF2-HERC2 和 NRF2-VAMP8/NCOA4 轴对控制铁稳态和决定铁死亡敏感性的贡献。 另一个有趣的观察结果是,双 KO HERC2 / VAMP8细胞的行为与NFE2L2/NRF2单 KO 细胞相似,脱铁铁蛋白/NCOA4 的相似积累、LIP 增加、铁死亡标记物水平更高(COX2 和 4-HNE 加合物)证明了这一点。 ,并增强对铁死亡细胞死亡的敏感性。尽管铁死亡被定义为脂质过氧化和铁依赖性,但脂质过氧化、铁或两者是否对于铁死亡诱导至关重要尚不清楚。铁螯合可以阻止铁死亡诱导的事实表明,单独游离铁的积累对于诱导铁死亡是必要的且足够的。然而,很难将不稳定铁的铁死亡效应与脂质过氧化完全分离,因为不稳定铁本身具有氧化还原活性,其积累预计会导致脂质过氧化增加。

In summary, we not only identified a previously undiscovered function of NRF2 in iron signaling by controlling ferritin synthesis/degradation and maintenance of iron homeostasis through HERC2, VAMP8, and NCOA4 but also provided evidence that NRF2 inhibition can enhance free LIP and make cancer cells with high NFE2L2/NRF2 expression specifically vulnerable to ferroptotic inducers. Furthermore, we have also provided proof of concept for the translational value of our findings using three preclinical models, suggesting that a combination therapy tailored around NRF2 inhibition and ferroptosis induction represents an effective therapeutic strategy to treat cancer patients. This study signifies a critical step before ferroptotic inducers can be successfully used in the clinic as the next generation of cancer therapy to treat resistant, refractory, and recurrent cancers.

总之,我们不仅通过 HERC2、VAMP8 和 NCOA4 控制铁蛋白合成/降解和维持铁稳态,确定了 NRF2 在铁信号转导中以前未被发现的功能,而且还提供了证据,证明 NRF2 抑制可以增强游离 LIP 并使癌细胞高NFE2L2/NRF2表达特别容易受到铁死亡诱导剂的影响。此外,我们还使用三个临床前模型为我们的研究结果的转化价值提供了概念证明,表明围绕 NRF2 抑制和铁死亡诱导定制的联合疗法代表了治疗癌症患者的有效治疗策略。这项研究标志着铁死亡诱导剂在临床上成功用作下一代癌症疗法来治疗耐药性、难治性和复发性癌症之前迈出了关键的一步。

MATERIALS AND METHODS 材料和方法

Chemicals and reagents 化学品和试剂