商业周刊 |大收获特朗普谈税收、关税、杰罗姆·鲍威尔等

《彭博商业周刊》在海湖庄园与这位前总统坐下来接受独家采访。

现在是六月下旬,唐纳德·特朗普正在海湖庄园俱乐部的镀金休赛期隔离中策划他的下一任总统任期。崇拜俱乐部的成员可能已经去凉爽的气候,但特朗普仍然心情很好。

民意调查显示,他和乔·拜登总统之间的竞争非常激烈,但他的筹款活动却如火如荼。现在也很清楚,他的34项重罪定罪并没有颠覆比赛。两天后,在第一次总统辩论中,将出现一个巨大的冲击,而拜登将陷入困境。然后,更大的一次将在7月13日到来,届时特朗普险些躲过刺客的子弹。

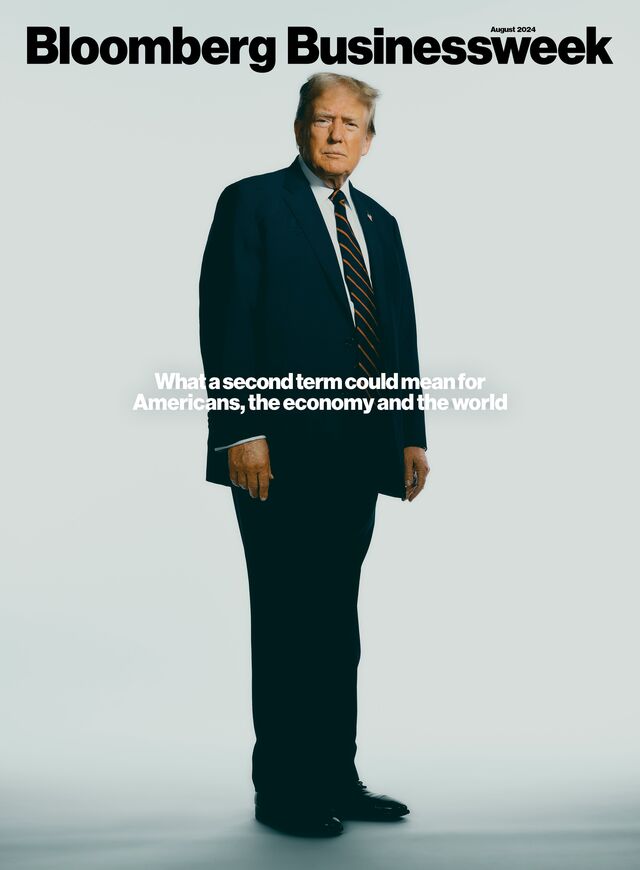

彭博商业周刊,2024年8月。立即订阅。摄影师:维克托略伦泰,彭博商业周刊

The Mar-a-Lago sitting room features a soaring red balloon tower dotted with giant gold ones reading “47,” shorthand for the next president—a gift from a local admirer who affixed a card gushing over “the best commander in chief America has ever known.” At Trump’s insistence, a staffer fetches the hot new fashion item he enjoys showing guests: a red MAGA-style cap emblazoned with “Trump Was Right About Everything.”

马阿拉歌的起居室里有一个高高的红色气球塔,上面点缀着巨大的金色气球,上面阅读“47”,这是下一任总统的简写--这是当地一位崇拜者送给他的礼物,他贴了一张卡片,上面写着“美国有史以来最好的总司令”。在特朗普的坚持下,一名工作人员拿出了他喜欢向客人展示的热门新时尚物品:一顶红色的MAGA风格的帽子,上面印着“特朗普对一切都是正确的”。

Outside Mar-a-Lago’s gates, the rest of the world isn’t so sure. There’s worry about what another Trump presidency could portend. Wall Street firms from Goldman Sachs to Morgan Stanley to Barclays have begun warning clients to expect higher inflation as Trump’s odds of recapturing the White House and imposing protectionist trade policies have risen. Giants of the American economy such as Apple, Nvidia and Qualcomm are grappling with how further confrontation with China could affect them and the chips everyone relies on. Democracies across Europe and Asia worry about Trump’s isolationist impulses, his shaky commitment to Western alliances, and his relationships with Chinese President Xi Jinping and Russian President Vladimir Putin. And while polls universally show that American voters favor Trump’s stewardship of the economy over Biden’s, it’s unclear to many exactly what they’ll get if they opt for another round with him.

在海湖庄园的大门之外,世界其他地方却不那么确定。人们担心特朗普再次当选总统可能预示着什么。从高盛(Goldman Sachs)到摩根士丹利(Morgan Stanley)再到巴克莱(Barclays)等华尔街公司已开始警告客户,随着特朗普夺回白宫并实施保护主义贸易政策的可能性上升,预计通胀将上升。苹果(Apple)、英伟达(Nvidia)和高通(Qualcomm)等美国经济巨头正在努力应对与中国的进一步对抗可能对它们以及所有人都依赖的芯片产生的影响。欧洲和亚洲的民主国家担心特朗普的孤立主义冲动、他对西方联盟的不稳定承诺,以及他与中国国家主席Xi近平和俄罗斯总统弗拉基米尔·普京(Vladimir Putin)的关系。虽然民意调查普遍显示,美国选民更喜欢特朗普对经济的管理,而不是拜登,但许多人不清楚如果他们选择与他进行另一轮谈判,他们会得到什么。

He waves away such concerns. “Trumponomics,” he says, equates to “low interest rates and taxes.” It’s “tremendous incentive to get things done and to bring business back to our country.” Trump would drill more and regulate less. He’d shut the Southern border. He’d squeeze enemies and allies alike for better trade terms. He’d unleash the crypto industry and rein in reckless Big Tech companies. In short, he’d make the economy great again.

他对这种担忧不屑一顾。他说,“特朗普经济学”等同于“低利率和低税收”。这是“完成任务并将业务带回我们国家的巨大激励。”特朗普会更多地开采石油,减少监管。他会关闭南部边境。为了更好的贸易条件,他会压榨敌人和盟友。他将释放加密行业,并控制鲁莽的大型科技公司。简而言之,他会让经济再次繁荣。

That’s the sales pitch, anyway. The plain truth is that no one really knows what to expect. So Bloomberg Businessweek went to Mar-a-Lago in Palm Beach, Florida, to press Trump for answers.

这就是推销的方式简单的事实是,没有人真正知道会发生什么。因此,《彭博商业周刊》前往位于佛罗里达棕榈海滩的海湖庄园,向特朗普施压,要求他给出答案。

In a wide-ranging interview on business and the global economy, he says that, if he wins, he’ll allow Jerome Powell to serve out his term as chair of the Federal Reserve, which runs through May 2026. Trump wants to bring the corporate tax rate to as low as 15%, and he no longer plans to ban TikTok. He’d consider Jamie Dimon, chairman and chief executive officer of JPMorgan Chase & Co., to serve as secretary of the Department of the Treasury.

在一次关于商业和全球经济的广泛采访中,他说,如果他赢了,他将允许杰罗姆鲍威尔担任联邦主席,直到2026年5月。特朗普希望将公司税率降至15%,他不再计划禁止TikTok。他会考虑摩根大通(JPMorgan Chase & Co.)董事长兼首席执行官杰米?戴蒙(Jamie Dimon),担任财政部部长

Trump is cool to the idea of protecting Taiwan from Chinese aggression and to US efforts to punish Putin for invading Ukraine. “I don’t love sanctions,” he says. He keeps circling back to William McKinley, who he says raised enough revenue through tariffs during his turn-of-the-20th-century presidency to avoid instituting a federal income tax yet never got the appropriate credit.

特朗普对保护台湾免受中国侵略的想法以及美国惩罚普京入侵乌克兰的努力很冷淡。“我不喜欢制裁,”他说。他不断回到威廉麦金利,他说,在20世纪之交的总统任期内,麦金利通过关税筹集了足够的收入,以避免征收联邦所得税,但从未得到适当的信贷。

And Trump (who has a proclivity to lie) insists he won’t pardon himself if convicted of a federal crime in the three federal cases pending against him: “I wouldn’t consider it.” He may not have to—on July 15, a Trump-appointed federal judge dismissed charges that he mishandled classified documents. (The special counsel swiftly announced he would appeal the decision.)

特朗普(他有撒谎的倾向)坚称,如果在三起针对他的联邦案件中被判犯有联邦罪行,他不会原谅自己:“我不会考虑。”他可能不必这么做--7月15日,特朗普任命的一名联邦法官驳回了对他不当处理机密文件的指控。(The特别检察官迅速宣布他将对这一决定提出上诉。

The broad strokes of Trumponomics might not be different from what they were during his first term. What’s new is the speed and efficiency with which he intends to enact them. He believes he understands the levers of power much more deeply now, including the importance of selecting the right people for the right jobs. “We had great people, but I had some people that I would not have chosen for a second time,” he says. “Now, I know everybody. Now, I am truly experienced.”

特朗普经济学的大致内容可能与他第一个任期内的情况没有什么不同。新的是他打算实施这些措施的速度和效率。他相信自己现在对权力的杠杆有了更深刻的理解,包括为合适的工作选择合适的人的重要性。“我们有很棒的人,但我有一些人,我不会选择第二次,”他说。“现在,我认识每个人。现在,我真的有经验了。”

Trump views his economic message as his best route to trouncing the Democrats in November, with Republicans devoting the opening night of their presidential convention to the theme of “wealth.” He’s betting that his unorthodox agenda of tax cuts, more oil, less regulation, higher tariffs and fewer foreign financial commitments will appeal to enough swing state voters to hand him the election. It’s also a gamble that voters will overlook the negative traits that characterized his first term in the White House: the personnel fights, the 180-degree policy shifts, the 6 a.m. social media pronouncements. And of course there’s the matter of the attempted insurrection on Jan. 6, 2021.

特朗普认为他的经济信息是他在11月击败民主党人的最佳途径,共和党人将总统大会的开幕之夜奉献给了“财富”的主题。他打赌,他的非正统议程减税,更多的石油,更少的监管,更高的关税和更少的外国金融承诺将吸引足够的摇摆州选民交给他的选举。这也是一场赌博,选民们会忽视他在白宫第一个任期内的负面特征:人事争斗、180度的政策转变、早上6点的社交媒体声明。当然还有2021年1月6日的未遂叛乱。

Already, polling shows signs that Black and Hispanic men are shifting to the Republican Party as they tire of historically high prices for food, housing and gas. As many as 20% of Black men now back Trump, though some pundits think those numbers are overstated. Either way, Biden is struggling to sell key voters on his economic record, which includes a very low unemployment rate and rising wages. He’s also facing down panic over his age. Trump could win in November, and many Democratic leaders are increasingly concerned he’ll deliver Republicans control of the House and Senate along with the White House.

民意调查已经显示,有迹象表明,黑人和西班牙裔男子正在转向共和党,因为他们厌倦了历史上的食品、住房和天然气价格高企。多达20%的黑人男性现在支持特朗普,尽管一些专家认为这些数字被夸大了。无论哪种方式,拜登都在努力向关键选民推销他的经济记录,其中包括极低的失业率和不断上涨的工资。他还面临着对自己年龄的恐慌。特朗普可能会在11月获胜,许多民主党领导人越来越担心他会让共和党人控制众议院和参议院沿着白宫。

In that case, he’d have unprecedented leverage to shape the US economy, the climate for global businesses and trade with allies. His first term demonstrated that he prefers to work one-on-one, which would give the CEOs and world leaders who have the best relationships with him an advantage while leaving his enemies falling short, and perhaps even fearful of what he’ll do. If one thing stands out from Businessweek’s interview with Trump, it’s that he’s fully aware of this power—and he has every intention of using it.

在这种情况下,他将拥有前所未有的影响力来塑造美国经济、全球商业环境以及与盟友的贸易。他的第一个任期表明,他更喜欢一对一的工作,这将给那些与他关系最好的首席执行官和世界领导人带来优势,同时让他的敌人功亏一篑,甚至可能害怕他会做什么。如果说《商业周刊》对特朗普的采访中有一点特别突出的话,那就是他完全意识到了这种力量--而且他完全打算使用这种力量。

On the US Economy 对美国经济

Trump, in a dark suit and tie, holds court in the cool afternoon darkness of Mar-a-Lago’s chintz-and-gold sitting room, keen as always to play the magnanimous host. He takes it upon himself to order a round of Cokes and Diet Cokes for his visitors, then gets down to explaining how he’d govern if reelected in November.

特朗普身穿深色西装,打着领带,在马阿拉歌庄园(Mar-a-Lago)的印花棉布和金色客厅里,在凉爽的午后黑暗中主持会议,一如既往地热衷于扮演宽宏大量的主人。他主动为客人点了一轮可乐和健怡可乐,然后开始解释如果11月再次当选,他将如何执政。

Business leaders prize stability and certainty. They didn’t get much of either in Trump’s first presidency. This time around, his campaign is more professionally run, but he hasn’t produced a detailed economic policy agenda to reassure them. The vacuum has generated confusion among those who are planning for a second Trump term.

Trump’s Economic Policy Inner Circle

In late April, a few of Trump’s informal policy advisers leaked to the Wall Street Journal an explosive draft proposal to severely curb the independence of the Federal Reserve. It was broadly inferred that Trump had endorsed the idea, which didn’t seem like a stretch given his prior attacks on Powell. In fact, the Trump campaign insisted he’d endorsed neither the proposal nor the leak, and his top campaign brass were furious about it. But the episode was a consequence of Trump’s still-unformed policy, which has left wonks from such think tanks as the Heritage Foundation battling to fill in the details and jockey for influence. Other conservative policy entrepreneurs have been pushing proposals to devalue the dollar or institute a flat tax.

At Mar-a-Lago, Trump makes it clear he’s fed up with the unauthorized freelancing. “There’s a lot of false information,” he complains. He’s eager to set the record straight on several topics.

First, there’s Powell. He told Fox News in February that he wouldn’t reappoint the Fed chair; now he states unequivocally that he’ll let Powell finish his term, which would last well into a second Trump administration.

“I would let him serve it out,” Trump says, “especially if I thought he was doing the right thing.”

Even so, Trump has thoughts on interest-rate policy, at least in the near term. The Fed, he warns, should abstain from cutting rates before the November election and giving the economy, and Biden, a boost. Wall Street fully expects two interest-rate cuts before the end of the year, including one, crucially, before the election. “It’s something that they know they shouldn’t be doing,” he says.

Next on his mind: inflation. Trump has been endlessly critical of Biden’s stewardship of the economy. But he sees, in the anger generated by high prices and interest rates, an opportunity to woo voters who typically don’t support Republicans, such as Black and Hispanic men. Trump says he’ll bring down prices by opening up the US to more oil and gas drilling. “We have more liquid gold than anybody,” he says.

Third is immigration. He believes harsh restrictions are key to boosting domestic wages and employment. He characterizes immigration restrictions as “the biggest [factor] of all” in how he’d reshape the economy, with particular benefits for the minorities he’s eager to win over. “The Black people are going to be decimated by the millions of people that are coming into the country,” he says. “They’re already feeling it. Their wages have gone way down. Their jobs are being taken by the migrants coming in illegally into the country.” (According to the US Bureau of Labor Statistics, the majority of employment gains since 2018 have been for naturalized US citizens and legal residents—not migrants.)

Trump’s language turns apocalyptic. “The Black population in this country is going to die because of what’s happened, what’s going to happen to their jobs—their jobs, their housing, everything,” he continues. “I want to stop that.”

Drilling for oil aside, Trump hasn’t detailed a plan for lowering prices. His personal conviction that the robust tariffs he’s proposing will produce a US windfall isn’t shared by mainstream economists, who warn that they’ll spur further inflation and amount to a tax increase for US households. A report from the Peterson Institute for International Economics estimates that his tariff regime would impose an additional annual cost of $1,700 for the average middle-income family. And Oxford Economics, a nonpartisan research group, estimates that Trump’s combination of tariffs, immigration restrictions and extended tax cuts could also increase inflation and slow economic growth. The through line of these policies, says Bernard Yaros, lead US economist at Oxford Economics, is “an increase in inflation expectations.”

Then there’s the budget deficit. Trump’s desire to renew his landmark 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act—estimated price tag: $4.6 trillion—and to further reduce corporate taxes doesn’t pencil out to a balanced budget in any way that he or his advisers have yet explained. Coupled with the upward pressure on interest rates that economists expect from his protectionist policies, Trump’s plans could exacerbate the country’s growing debt burden.

In the end, however, Trump’s other positions could be enough to sway business leaders to his side. Harold Hamm, a Trump donor and the executive chairman of oil giant Continental Resources Inc., writes in an email: “There seems to be outright hostility to free markets in the Biden Administration. As a result, capital is parked on the sidelines. Why? Because of regulatory uncertainty and in some cases downright regulatory hostility toward certain sectors.” Hamm cites the pause Biden put on liquefied natural gas projects in January as one example. “When Trump is re-elected,” he predicts, “that capital that was parked on the sidelines will be unleashed once again.”

On US Business Leaders

Corporate America is still adjusting to the likelihood of Trump’s return. Privately, many CEOs aren’t thrilled. “They can’t stand him,” says Jeffrey Sonnenfeld, a Yale School of Management professor who runs a leadership institute for CEOs and speaks regularly with many top executives. Nevertheless, they recognize that a shotgun remarriage could be in the offing.

On June 13, Trump met privately in Washington with dozens of the country’s most prominent chief executives, a group that included JPMorgan’s Dimon, Tim Cook of Apple and Brian Moynihan of Bank of America. The occasion was a “fireside chat” put on by the Business Roundtable, a nonpartisan lobbying group. The gathering brought Trump face-to-face with a number of corporate leaders with whom he’s long had a vexed relationship. Many were leery of him from the outset of his presidency; some spoke out publicly after the Jan. 6 attacks on the US Capitol by his supporters. Cook, Dimon and Moynihan all condemned the violence, with Cook calling it “a sad and shameful chapter in our nation’s history.” Yet just weeks after a Manhattan jury convicted Trump of 34 felonies, everyone dutifully assembled to commune with him—an unmistakable sign of the shifting power dynamic.

Trump is highly attuned to his standing with America’s corporate chieftains, and he vacillates between wanting their approval and hoping to bend them to his will. At Mar-a-Lago, when he’s presented with the July issue of Businessweek, featuring LVMH Louis Vuitton Moët Hennessy SE CEO Bernard Arnault on the cover, he refers to Arnault, one of the world’s richest men, as “an incredible guy, a friend of mine I think,” and asks whether this relationship had come up. (It hadn’t.)

Trump bristles when it’s pointed out to him that no Fortune 100 CEO has publicly contributed to his campaign. (Since then, Elon Musk has pledged financial support.) And he’s still smarting from CNBC’s coverage of the Business Roundtable meeting, which featured quotes from an anonymous CEO who slammed Trump as “remarkably meandering” and “all over the map.”

On the contrary, the meeting was “a lovefest,” Trump insists. “I will tell you when I’m not loved, because I feel that better than anybody,” he says. “CNBC called and apologized to me, because they found that we had a great meeting.” (A CNBC spokesperson writes: “We did not apologize. We spoke to the former president about keeping the lines of communication open.”)

Trump says he reminded the assembled executives that in 2017 he slashed the corporate tax rate “from 39% to 21%” (actually from 35% to 21%) and vowed to push it lower still, to 20%. “They loved it, they were happy,” he recalls. He adds that he wants to cut the rate even lower than that: “I would like to get it down to 15.”

But Trump is also aware that whatever “love” the CEOs might have expressed was ultimately driven by self-interest: They can read election polls like everyone else. “Whoever’s leading gets all the support they want,” he says. “I could have the personality of a shrimp, and everybody would come.”

This wasn’t always the case. With Trump disgraced and seemingly finished in politics after his efforts to overturn the 2020 presidential election, the Republican business community was part of a coalition eager to anoint a new standard-bearer for the party. It began lavishing money and attention on a rising generation of business-friendly politicians, led by Florida Governor Ron DeSantis, former South Carolina Governor Nikki Haley and Virginia Governor Glenn Youngkin, who has also served as co-CEO of the investment firm Carlyle Group Inc. But in 2024, DeSantis’ presidential campaign collapsed, Haley’s petered out, and Youngkin’s never took place. Business leaders were shocked and crestfallen as Trump cruised to the nomination.

“Everyone read this wrong,” says Liam Donovan, a Republican business lobbyist. “There was a core assumption that Trump was finished. But DeSantis was never going to be the guy, nor was Haley. People saw an opportunity to turn the page, tried to make it happen, and it didn’t happen. The base wanted Trump.”

Trump famously carries grudges: At a conservative political conference last year, he pledged to deliver “retribution.” But asked at Mar-a-Lago whether he’ll go after CEOs he dislikes, he demurs. “I don’t have [plans for] retribution against anyone,” he says.

He does rekindle long-running feuds with Meta Platforms Inc. CEO Mark Zuckerberg and Amazon.com Inc. founder and Washington Post owner Jeff Bezos. Bezos, whose newspaper kept a running tally of false claims Trump made while president (it reached 30,573), draws particular ire. Trump says Bezos has “done a great disservice to himself” and made “a lot of enemies” with his ownership of the Post.

For all his corporate critics and enemies, Trump doesn’t lack support in the boardroom or on Wall Street. “The Trump economy was very good,” says Scott Bessent, CEO of Key Square Capital Management LLC and a top Trump donor. “It worked for people at the top and at the bottom. The market was good. Real wages increased. It was a very good time.”

Other prominent CEOs who don’t identify as Trump partisans have also been praising his presidency. “Be honest,” Dimon said at the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland, in January. “He was kind of right about NATO, kind of right about immigration. He grew the economy quite well. Tax reform worked. He was right about some of China. … He wasn’t wrong about some of these critical issues, and that’s why they’re voting for him.”

Trump relishes the compliment. He’s changed his view of the man he attacked on Truth Social last year as “Highly overrated Globalist Jamie Dimon” and now says he could envision Dimon, who’s thought to be contemplating a political career, as his secretary of the Treasury. “He is somebody that I would consider,” Trump says. (A spokesperson for Dimon declined to comment.)

For all his periodic wrath toward business leaders, Trump appears eager to have them serve in a second administration. North Dakota Governor Doug Burgum, a former tech CEO, made Trump’s short list for vice president and is likely to land in his cabinet. Bessent is also a candidate for Treasury secretary. Trump is even embracing CEOs who, not long ago, were considered possible challengers. “Glenn Youngkin is prime time,” he says in a post-interview aside. “I’d love to have him in my administration.” And Trump’s ultimate pick as running mate, JD Vance, was a venture capitalist for years.

Still, many chief executives feel trepidation about a Trump renaissance. Ken Chenault, the former chairman and CEO of American Express Co., says Trump’s threats have had a chilling effect on corporate leaders. “People are staying on the sidelines,” he says, “because they greatly fear that there will be retribution.” Chenault raises another example of that happening during Trump’s presidency: his opposition to the $85 billion AT&T-Time Warner merger and concerns he was trying to force a sale of CNN over displeasure with its coverage of his administration.

Current CEOs, Chenault says, are terrified of winding up in Trump’s crosshairs: “The fear is real.”

On Foreign Policy

As president, Trump shattered the long-standing Republican orthodoxy of favoring free trade. He says he’ll go further if reelected. At Mar-a-Lago he offers an impassioned defense of US tariffs—he’s been studying McKinley, dubbing him “the Tariff King”—to make it clear he intends to ratchet up levies not just on China but on the European Union, too.

“McKinley made this country rich,” Trump says. “He was the most underrated president.” In Trump’s reading of history, McKinley’s successors squandered his legacy on costly government programs such as the New Deal (“the whole thing with the parks and the dams”) and unjustly poisoned an important tool for economic statecraft. “I can’t believe how many people are negative on tariffs that are actually smart,” Trump says. “Man, is it good for negotiation. I’ve had guys, I’ve had countries that were potentially extremely hostile coming to me and saying, ‘Sir, please stop with the tariff stuff.’”

To the consternation of many business and consumer groups, Biden maintained Trump’s tariffs on China, even increasing ones on steel, aluminum, semiconductors, electric vehicles, batteries and other goods. “This is going to add price inflation across the board, all in the name of ‘tough guy’ election-year politics,” Yaël Ossowski, deputy director of the Consumer Choice Center, a nonpartisan advocacy group, said in May.

In Trumpworld, however, Biden’s actions are seen as validation that Trump was right—and his Democratic critics were wrong—about the threat China poses to the US economy and security. Trump is eager to prescribe more of the same medicine, including to European allies. In addition to targeting China for new tariffs of anywhere from 60% to 100%, he says he’d impose a 10% across-the-board tariff on imports from other countries, citing a familiar litany of complaints about foreign countries not buying enough US goods.

“The ‘European Union’ sounds so lovely,” Trump says. “We love Scotland and Germany. We love all these places. But once you get past that, they treat us violently.” He mentions reluctance in Europe to import US automobiles and agricultural products as key drivers of the more than $200 billion trade deficit, a statistic he considers a critical measure of economic fairness.

As with so much else, Trump views trade in personal terms. He speaks of it as though it were a private negotiation between himself and recalcitrant foreign leaders who understand full well that they’re exploiting the US and therefore must be curbed. He’s animated as he recounts a conversation with Angela Merkel, then Germany’s chancellor. “Angela, how many Fords or how many Chevrolets are there in the middle of Munich right now?” he remembers asking.

He mimics Merkel’s German accent in reply: “Oh, I do not believe many.”

“How about none?” he says he shot back.

Satisfied that he’s illustrated his point, Trump turns back to the Businessweek reporters. “They treat us very badly,” he says. “But I was changing all of that and that culture.” Return him to the White House, he suggests, and he’ll finish the job.

Trump’s transactional view of foreign policy and his desire to “win” every deal could have ramifications around the globe—and even rupture US alliances. Asked about America’s commitment to defending Taiwan from China, which views the Asian democracy as a breakaway province, Trump makes it clear that, despite recent bipartisan support for Taiwan, he’s at best lukewarm about standing up to Chinese aggression. Part of his skepticism is grounded in economic resentment. “Taiwan took our chip business from us,” he says. “I mean, how stupid are we? They took all of our chip business. They’re immensely wealthy.” What he wants is for Taiwan to pay the US for protection. “I don’t think we’re any different from an insurance policy. Why? Why are we doing this?” he asks.

Another factor driving his skepticism is what he regards as the practical difficulty of defending a small island on the other side of the globe. “Taiwan is 9,500 miles away,” he says. “It’s 68 miles away from China.” Abandoning the commitment to Taiwan would represent a dramatic shift in US foreign policy—as significant as halting support for Ukraine. But Trump sounds ready to radically alter the terms of these relationships.

His views about Saudi Arabia, by contrast, are more amicable. He says he’s spoken to Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman Al Saud within the past six months, though he declines to elaborate on the nature and frequency of their talks. Asked if he worries that increasing US oil and gas production would upset the Saudis, who wish to maintain their primacy in energy, Trump replies that he doesn’t think so, pointing once more to a personal relationship. “He likes me, I like him,” he says of the crown prince. “They’re always going to need protection … they’re not naturally protected.” He adds: “I’ll always protect them.”

Trump blames Biden and former President Barack Obama for eroding US relations with Saudi Arabia, saying they pushed the country toward a key adversary. “They’re not with us anymore,” he says. “They’re with China. But they don’t want to be with China. They want to be with us.”

He has reasons beyond American foreign policy for favoring closer ties with the Saudis. Hundreds of millions of dollars are at stake for him. On July 1 the Trump Organization and DAR Global announced plans to build a Trump Tower and luxury hotel in Jeddah. An investment fund founded by his son-in-law Jared Kushner has also taken a $2 billion investment from the Saudi government’s wealth fund.

Western allies, now familiar with Trump’s personal and mercurial approach to foreign policy, are taking extensive measures to prepare for his possible return to the White House. These include increasing defense spending, transferring control of military aid for Ukraine to NATO, racing to improve relationships with Trump’s advisers and affiliated think tanks, and reaching out to Republican governors and thought leaders to divine his intentions. At a NATO summit in Washington, Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskiy urged allies to act quickly to help his country repel Russia’s invasion instead of waiting for the election results in November to decide what to do.

Dan Caldwell, a policy adviser at the right-leaning think tank Defense Priorities, says that “it’s actually in Europe’s interest to ‘America-proof’ their defense and to start operating on the assumption that the United States has other, more urgent national security priorities, and domestic ones as well.”

On Silicon Valley

During his presidency and afterward, Trump frequently took aim at the US tech industry. For much of that time, Twitter (now X) was his platform of choice for venting displeasure with companies such as Facebook, Google and Twitter itself, pre-Elon Musk. In 2020 he signed an executive order reducing legal protections for social media platforms under Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act of 1996. And his government launched antitrust probes into Amazon, Apple, Facebook and Google—actions carried on and expanded under Biden.

Trump’s attacks on Big Tech have never been ironclad statements of policy or principle, exactly. Not unlike his tariff proposals, they’ve served at least as much as leverage plays—his staking out negotiating positions that companies and CEOs must respond to. The central complaint he and Republicans used to make was that tech companies were biased against conservatives—shadow-banning them, deplatforming them and (allegedly) suppressing right-leaning sources in search results. Today, Trump’s focus is on a more broadly appealing charge: that out-of-control tech companies are harming children—to the point, even, of causing a nationwide epidemic of suicides. “They have become too big, too powerful,” he argues. “They’re having a huge negative impact on, especially, young people.”

This position may stem from Trump’s understanding of how televised drama can shape public opinion. In February, during a Senate hearing of tech executives, Zuckerberg was effectively bullied into apologizing to families in the audience who said social media abuse had driven their children to suicide. It was an arresting moment, and Trump has harnessed the charge for his campaign. “I don’t want them destroying our youth,” he says of the social media companies. “You see what they’re doing—including, even, suicides.”

Moments later, however, he’s defending many of these same platforms as vital bulwarks against Chinese technological supremacy. Trump wants to personally dominate the US companies, but he doesn’t want foreign competitors replacing them. “I respect them greatly,” he insists of the companies he was just bashing. “If you go after them very violently, you can destroy them. I don’t want to destroy them.”

At Mar-a-Lago, the one exception to his claim to not want to harm US tech companies, and to privilege domestic ones over foreign ones, is TikTok. Discussing his recent embrace of the Chinese-owned social media platform, where he’s already quite popular, Trump mentions that banning it in the US would benefit a company and a CEO he has no desire to reward. “Now [that] I’m thinking about it, I’m for TikTok, because you need competition,” he says. “If you don’t have TikTok, you have Facebook and Instagram—and that’s, you know, that’s Zuckerberg.” It’s an outcome he won’t abide. He’s still stung by Facebook’s decision to bar him indefinitely in the wake of the Jan. 6 attacks. “All of a sudden,” Trump grouses, “I went from No. 1 to having nobody.”

His reversal on cryptocurrency has been marked by similar dynamics. Not long ago he criticized Bitcoin as a “scam” and a “disaster waiting to happen.” Now he says it and other cryptocurrencies should be “made in the USA.” He frames this about-face as a practical necessity. “If we don’t do it, China is going to figure it out, and China’s going to have it—or somebody else,” he says.

Not coincidentally, the crypto industry—spurned by the Democratic Party, brimming with cash and eager for friends in Washington—has now found its way to Trump. “Thanks largely to the actions of the Securities and Exchange Commission, the Biden administration has stumbled into becoming anti-crypto,” says Justin Slaughter, policy director at the crypto-focused investment firm Paradigm. “Given that about 20% of Democrats own crypto, per polling, and its ownership skews young and non-White, this was politically unwise.” Trump has moved to fill the void, declaring in a May speech that he would “stop Joe Biden’s crusade to crush crypto.” The following month he reaped the benefits, raising money from Bitcoin miners at a Mar-a-Lago fundraiser. Trump’s campaign then announced it would “build a crypto army,” and it now accepts crypto contributions.

Some in Silicon Valley have learned that the best way to get Trump to alter his position on something is to appeal to him directly. That was certainly the case for Tim Cook. In 2019, Apple Inc. looked set to be a victim of Trump’s trade war with China, with billions of dollars at stake, as the president announced 25% import tariffs. He then publicly rejected Apple’s request for an exclusion. “Apple will not be given Tariff waiver, or relief, for Mac Pro parts that are made in China,” he wrote on Twitter. “Make them in the USA, no Tariffs!”

At Mar-a-Lago, Trump speaks fondly of Cook and reveals how Apple’s CEO persuaded him to relent. He recalls Cook reaching out privately and asking, “Could I come in and see you?” Trump appreciated the gesture of respect from the head of what at the time was the world’s most valuable company. “That’s impressive,” Trump says. “I said, ‘Yeah, come in.’” Trump remembers that Cook was straightforward. “He said to me, ‘I need help, you have tariffs of 25% and 50% [on Apple products imported from China],’” he recalls. “He said, ‘It would really hurt our business. It would destroy our business, potentially.’” (An Apple spokesperson declined to comment.)

Trump wasn’t looking to do that—mainly, he wanted to demonstrate that he could bring manufacturing jobs back to the US, as he’d promised to do. In his telling, he prevailed upon Cook to expand domestic production. “I said, ‘I’m gonna do something for you guys,’” Trump recalls, “‘but you have to build in this country.’” Four months later, Apple announced it was beginning construction on a campus in Austin. The press release quoted Cook saying: “Building the Mac Pro, Apple’s most powerful device ever, in Austin is both a point of pride and a testament to the enduring power of American ingenuity.” Cook then gifted Trump a $5,999 Mac Pro, one of the first made at the Texas factory.

Had Trump forced Cook’s hand? Doubtful. Apple had originally announced a year earlier that it would invest $1 billion in a new Austin campus, and Mac Pros had been assembled at existing Texas facilities since the Obama era. Nevertheless, the episode registered as a positive for Trump and established Cook at the opposite end of his personal CEO continuum from Zuckerberg. It also created a potential road map for how tech CEOs might navigate a second Trump term.

“I found him to be a very good businessman,” he says of Cook.

On the Uncertain Future

What Trump thinks about American businesses and the people who run them suddenly matters more than ever. So do his views on the Fed, the economy and every important issue around the globe.

The shock of Biden’s faltering debate performance on June 27 supercharged doubts about the president’s cognitive health and plunged the Democratic Party into an existential crisis. It also gave Trump a measurable lead in many polls—and, along with narrowly surviving the assassination attempt, may have amplified his already formidable sense of political inviolability.

“The debate certainly had a big impact,” he says in a July 9 follow-up call, four days before the shooting. “A lot of the states are just starting now to come out, and it shows a very big swing.” Asked whether Biden should drop out of the race, he says, “That’s a decision he has to make. But I do think our country is in great danger whether he stays in or drops out.” On Vice President Kamala Harris, considered a likely alternative at the top of a Democratic ticket, Trump says, “I don’t think it would make much difference. I would define her in a very similar [way] that I define him.” With months to go before Election Day, there’s plenty of time for the dynamics of the race to change.

But even back at Mar-a-Lago, a few days before Biden’s debate stumble, Trump seemed to be riding this heightened sense of good fortune. When the resort’s longtime managing director dropped by during the conversation, Trump noted with pride that the club would increase its initiation fee from $700,000 to $1 million in October, with four new slots open—a sign, presumably, of the increased value of proximity to potentially the next commander-in-chief.

And at the conclusion of our interview, Trump, boastful to the very end, tried to send Businessweek off with that new MAGA hat (“Trump Was Right About Everything”). We politely declined. That’s ultimately for the voters to decide.

(Corrects length of Powell’s term as chair of the Federal Reserve in seventh paragraph.)