Hatching a Conspiracy: A BIG Investigation into Egg Prices

策划阴谋:对蛋价的重大调查

'More hens, less income!' So said the United Egg Producers' economist Donald Bell in 1994. The industry has gotten more consolidated ever since. And avian flu is just the latest excuse to hike prices.

“更多的母鸡,收入更少!”这是美国蛋品生产者协会的经济学家唐纳德·贝尔在 1994 年所说的。从那时起,行业变得更加集中。而禽流感只是抬高价格的最新借口。

This issue is part one of a three-part series on the egg industry. It is written by antitrust lawyer Basel Musharbash, based in part on a report he researched for Farm Action.

本期是关于蛋类产业三部分系列的第一部分。这篇文章由反托拉斯律师巴塞尔·穆沙巴什撰写,部分基于他为农业行动研究的报告。

Over the past two months, egg prices have become a political football. Journalists are reporting in depth on the industry, egg consolidation has come up in a Congressional antitrust hearing, and Donald Trump mentioned a plan to tackle egg prices in the State of the Union speech, putting his Secretary of Agriculture Brooke Rollins on notice that she has to get the price down. Most notably, earlier this week, the Capitol Forum reported the Department of Justice Antitrust Division is now investigating egg markets.

在过去的两个月里,鸡蛋价格成为了政治斗争的焦点。记者们对这一行业进行了深入报道,鸡蛋行业整合在国会反垄断听证会上被提及,唐纳德·特朗普在国情咨文中提到了应对鸡蛋价格的计划,并提醒农业部长布鲁克·罗林斯必须降低价格。最引人注目的是,本周早些时候,《国会论坛》报道称,司法部反垄断局正在对鸡蛋市场展开调查。

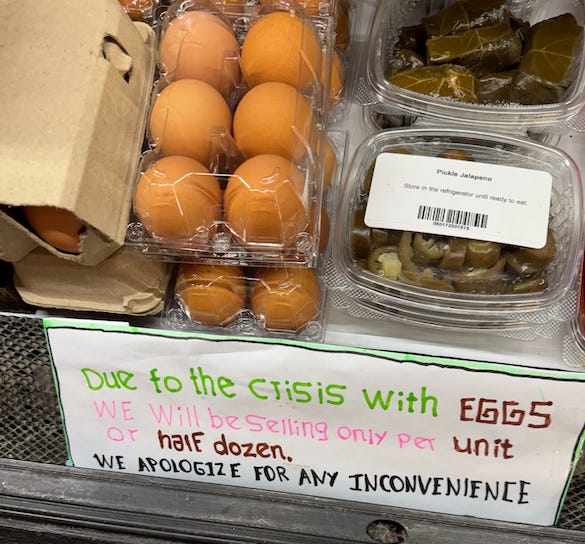

The reason is simple. For most Americans, eggs have always been cheap, and thus a key food staple. And now eggs are expensive, and sometimes in shortage. Over the past year egg prices have increased by 53%— jumping 15% in January alone. As of the beginning of February, egg producers were charging wholesale buyers an average of $5.95 for a dozen eggs, and retailers were charging consumers anywhere between $4 and $9 a dozen — and sometimes even more.

原因很简单。对大多数美国人来说,鸡蛋一直是廉价食物,因此是重要的主食。而现在鸡蛋价格昂贵,有时甚至出现短缺。在过去的一年里,鸡蛋价格上涨了 53% —— 仅在 1 月份就上涨了 15%。截至 2 月初,鸡蛋生产商向批发买家收取的平均价格为每打鸡蛋 5.95 美元,而零售商向消费者收取的价格则在每打 4 美元到 9 美元之间 —— 有时甚至更高。

The high prices, and sometimes shortages, are a problem in and of themselves, but they also represent that the American system has gone askew. If we can’t even get a cheap omelet or egg sandwich anymore, what can America do right?

高价格,有时还伴随着短缺,本身就是一个问题,但它们也代表了美国体系的失衡。如果我们连便宜的煎蛋卷或蛋三明治都买不到,那么美国还能做对什么呢?

The stated reason for the high price of eggs is something that happens periodically: an avian flu epidemic. Since 2022, outbreaks of bird flu on poultry farms have led to the culling of over 115 million egg-laying hens. This epidemic, according to the prevailing narrative, has driven egg prices up to record highs all on its own. As one industry executive put it, it’s all just “supply disruption, ‘act of God’ type stuff.” The popular response to this story has been what you’d expect: Scientists are discussing flu vaccines for chickens, politicians are blaming each other about bird culls, and many are concerned about how the massive scale of today’s egg farms enables—and exacerbates—avian flu epidemics. And none of that is necessarily wrong.

高蛋价的原因是周期性发生的事情:禽流感疫情。自 2022 年以来,禽流感在养鸡场的爆发导致超过 1.15 亿只产蛋母鸡被扑杀。根据主流叙述,这场疫情使蛋价飙升至历史新高。一位行业高管表示,这一切只是“供应中断,‘天灾’之类的事情。”公众对此事件的反应是可预见的:科学家们在讨论鸡只的流感疫苗,政治家们相互指责关于禽类扑杀的责任,许多人则担心如今大规模的蛋鸡养殖场是如何助长并加剧禽流感疫情的。而这些担忧并不一定都是错误的。

But something doesn’t add up about this “avian flu is the sole and natural cause of high egg prices” story. Despite the “act of God” going on — and the skyrocketing prices accompanying it — egg production is actually . . . not down by all that much. 115 million hens is a lot of birds to cull, but it’s important to put the loss of those hens in context: They weren’t lost all at once. They were lost over three years. And there have always been around 300 million other hens alive and kicking to lay eggs for America—not to mention a continuous pipeline of 120-130 million female chicks (called “pullets”) in the process of being raised into adult hens to replace the ones dying or aging out.

但关于“禽流感是鸡蛋价格上涨的唯一自然原因”这个故事,有些事情让人觉得不太对劲。尽管正在发生“天灾”,伴随而来的是价格飞涨,但鸡蛋生产实际上并没有下降太多。1.15 亿只母鸡的淘汰数量确实很大,但重要的是将这些母鸡的损失放在背景中来看:它们并不是一下子全部被淘汰的,而是在三年内逐渐减少的。而且,美国一直有大约 3 亿只其他健康的母鸡在产蛋——更不用说在养殖过程中持续有 1.2 亿到 1.3 亿只小母鸡(称为“雏鸟”)正在被养成可替代已死亡或老化母鸡的成年母鸡。

As a result of this pipeline, the effect of avian flu outbreaks on egg production, while not insignificant, has been relatively small. Monthly egg production during each of the last three years has averaged only 3-5% lower than it was in 2021, the year before the epidemic started. Meanwhile, demand for eggs has actually declined. According to private reports by the Egg Industry Center, Americans went from consuming around 206 shell eggs each in 2021 to consuming less than 190 shell eggs each in 2024 — a ~7.5-percent nosedive. As many countries have closed their markets to American eggs since 2021 on account of the avian flu, egg exports have also fallen off a cliff — going down by nearly half between 2021 and 2022 and staying there ever since. That dynamic, according to my analysis of USDA data, has shaved another ~2.5% off aggregate demand on U.S. egg production.

由于这一管道,禽流感暴发对鸡蛋生产的影响虽然不容忽视,但相对较小。在过去三年的每个月,鸡蛋的平均生产量仅比 2021 年(疫情爆发前一年)低 3-5%。与此同时,鸡蛋的需求实际上有所下降。根据鸡蛋产业中心的私营报告,2021 年美国人每人消费约 206 个鸡蛋,而到 2024 年这一数字降至不到 190 个鸡蛋,下降幅度约为 7.5%。由于许多国家自 2021 年以来因禽流感关闭了对美国鸡蛋的市场,鸡蛋出口也大幅减少——在 2021 年至 2022 年之间几乎减少了一半,并且此后一直保持在那个水平。根据我对农业部数据的分析,这种动态又使美国鸡蛋生产的总需求减少了约 2.5%。

So, reports of an unprecedented egg “shortage” are exaggerated. Nonetheless, egg prices — and egg company profits — have gone through the roof. Cal-Maine Foods — the largest egg producer and the only one that publishes its financial data as a publicly traded company — has been making more money than ever. It’s annual gross profits in the past three years have floated between 3 and 6 times what it used to earn before the avian flu epidemic started — breaking $1 billion for the first time in the company’s history. All of this extra profit is coming from higher selling prices, which have been earning Cal-Maine unprecedented 70-145 percent margins over farm production costs per dozen. Taking Cal-Maine as the “bellwether” for the industry’s largest firms — as people in the egg business do — we can be pretty confident that the other large egg producers are also raking in profits off the relatively small dip in egg production.

因此,有关前所未有的鸡蛋“短缺”的报告被夸大了。然而,鸡蛋价格——以及鸡蛋公司的利润——已经 skyrocketed。Cal-Maine Foods——最大的鸡蛋生产商,也是唯一一家以公开交易公司身份发布财务数据的公司——正在赚取前所未有的利润。在过去三年中,它的年毛利润在禽流感疫情开始之前的收益基础上浮动在 3 到 6 倍之间——首次突破 10 亿美元,创下公司历史新高。这些额外利润主要源于更高的销售价格,使 Cal-Maine 每打鸡蛋的利润相对于农场生产成本达到了前所未有的 70-145%。以 Cal-Maine 作为行业大型公司的“风向标”——正如鸡蛋行业的人所说——我们可以相当有信心,其他大型鸡蛋生产商也在相对较小的鸡蛋生产下降中获取了利润。

High persistent profits are an anomaly for the industry. Historically, egg producers have responded to avian flu epidemics—and the temporary rise in egg prices that often accompanies them—by quickly rebuilding and expanding their flocks of egg-laying hens. “Fowl plagues”—as these epidemics used to be called—have been with us since at least the 19th century. Most recently, large-scale avian flu epidemics hit egg farms in 2015 and 1983-1984. The egg industry responded to both of these destructive events by sprinting to rebuild and expand the egg-laying hen flock — something which checked price increases and ultimately made sure prices went back to pre-epidemic levels within a reasonable time.

高持久利润是该行业的一种异常情况。历史上,蛋鸡生产者在禽流感疫情——以及通常伴随而来的蛋价暂时上涨——发生时,迅速重建和扩展蛋鸡群。“禽流感”——正如这些疫情曾被称呼的——自 19 世纪以来就一直存在。最近,大规模禽流感疫情在 2015 年以及 1983 至 1984 年袭击了蛋鸡养殖场。蛋行业对这两次灾难性事件的反应都是迅速重建和扩展蛋鸡群——这避免了价格上涨,并最终确保价格在合理的时间内回到疫情前的水平。

As Cal-Maine Foods explained in its 2007 Annual Report: “In the past, during periods of high profitability, shell egg producers have tended to increase the number of layers in production with a resulting increase in the supply of shell eggs, which generally has caused a drop in shell egg prices until supply and demand return to balance.”

正如 Cal-Maine Foods 在其 2007 年年报中解释的:“过去,在盈利能力高的时期,壳蛋生产商往往会增加生产中的产蛋鸡数量,导致壳蛋供应增加,这通常会导致壳蛋价格下降,直到供需恢复平衡。”

For example, immediately after the height of the avian flu epidemic in May 2015, egg producers started adding millions more pullets to their operations each month—ultimately raising 15.3 million more pullets on their farms in 2015 than they did in 2014, and increasing that figure by another 8 million in 2016, according to my analysis of data from monthly USDA/NASS Chicken and Eggs reports. Altogether, producers added adult hens to their flocks at a prodigious rate of 4.15 million per month on average from August 2015 through February 2016, replacing nearly all of the hens lost to avian flu within 7 months.

例如,根据我对每月 USDA/NASS 鸡蛋报告数据的分析,在 2015 年 5 月禽流感疫情高峰后,蛋鸡生产商开始每个月增加数百万只雏鸡,最终在 2015 年比 2014 年多养了 1530 万只雏鸡,并在 2016 年再增加了 800 万只。总的来说,生产商在 2015 年 8 月至 2016 年 2 月期间平均每月以 415 万只的惊人速度向养殖场添加成年母鸡,在 7 个月内几乎替代了因禽流感损失的所有母鸡。

As a result, the average wholesale price of eggs landed at $1.65 a dozen that year, only 40 percent higher than it did the year before. By the end of March 2016, monthly egg production was higher than it was in March 2014 — and egg prices had not only returned to pre-epidemic levels, but were dropping even lower.

因此,平均批发价格在那年达到每打 1.65 美元,仅比前一年高出 40%。到 2016 年 3 月底,月鸡蛋产量已高于 2014 年 3 月——而鸡蛋价格不仅回到了疫情前的水平,甚至还在下降。

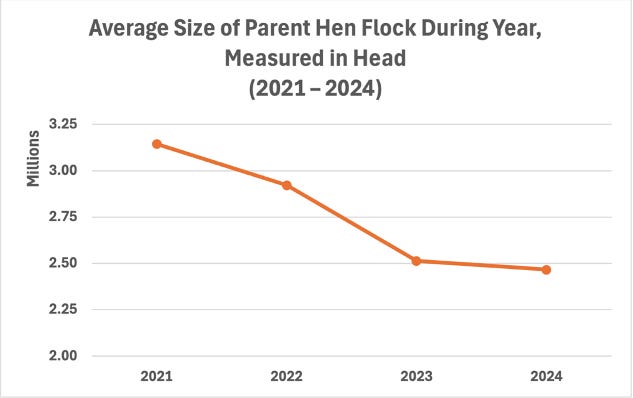

This time around, however, that’s not happening. Despite high profits, the egg industry has somehow maintained a stubborn deficit in egg production capacity. Hatcheries — the firms that supply hens to egg producers — have throttled the pipeline of hens instead of expanding it. According to the Egg Industry Center, the size of the flock of “parent” hens — the hens used by hatcheries to produce layer chicks for egg producers — plummeted from 3.1 million hens in 2021, to 2.9 million in 2022, to 2.5 million hens in 2023 and 2024.

不过这一次并没有发生这种情况。尽管利润高企,蛋鸡产业却以某种方式维持着产能的顽固亏损。孵化场——向蛋鸡生产商提供母鸡的公司——反而限制了母鸡的供给链,而不是扩大它。根据蛋工业中心的数据,“母”鸡的数量——即孵化场用来为蛋鸡生产商生产蛋鸡雏的母鸡——从 2021 年的 310 万只骤降至 2022 年的 290 万只,再到 2023 年和 2024 年的 250 万只。

Meanwhile, hatcheries have been hatching significantly fewer parent chicks to replace aging ones — nearly 380,000 (or 12 percent) fewer in 2022 compared to the year before, and even fewer parent chicks in 2023 and 2024 — leaving the parent flock older and more likely to produce eggs that fail to hatch. That could explain why, although hatcheries reported producing 125-200 million more fertilized eggs to the USDA in each of the last three years compared to 2021, the number of eggs they’ve placed in incubators and the number of chicks they’ve hatched from those eggs has either declined or stayed basically steady with 2021 levels in every year since.

与此同时,孵化场孵化的亲本小鸡数量显著减少——2022 年比去年减少了近 38 万只(或 12%),2023 年和 2024 年的亲本小鸡数量甚至更少——这使得亲本群体年龄更大,更可能产出无法孵化的蛋。这可能解释了为什么尽管孵化场在过去三年中向美国农业部报告了比 2021 年多出 1.25 亿到 2 亿个受精蛋,但自那年以来,他们放入孵化器的蛋数量和从这些蛋孵化的小鸡数量,均在每年有所下降或基本持平于 2021 年的水平。

巴塞尔·穆沙巴什制作的图表。数据来源:美国蛋鸡行业中心,《美国鸡群趋势与预测》(2025 年 2 月 6 日)。

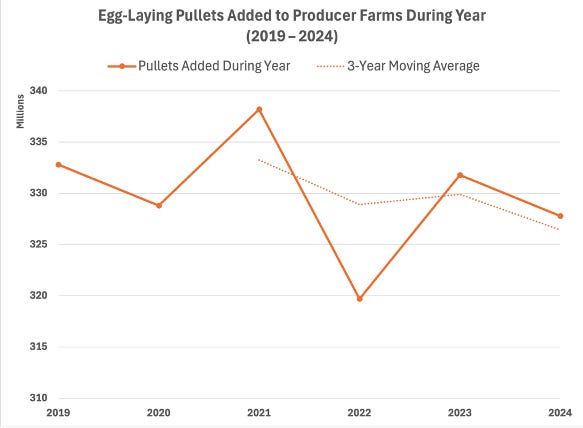

As for egg producers themselves, you may be surprised to learn that they have added between 5 and 20 million fewer pullets to their farms in every one of the last three years than they did in 2021. As the USDA observed with some astonishment at the end of 2022, “producers—despite the record-high wholesale price [of eggs]—are taking a cautious approach to expanding production[.]” The following month, it pared down its table-egg production forecast for the entirety of 2023 on account of “the industry’s [persisting] cautious approach to expanding production.”

就蛋鸡生产商而言,您可能会惊讶地发现,在过去三年中,他们每年在养殖场增加的雏鸡数量比 2021 年减少了 500 万到 2000 万只。正如美国农业部在 2022 年年底惊讶地观察到的,“尽管鸡蛋的批发价格创下历史新高,生产商们仍然对扩大生产采取谨慎的态度。”在接下来的一个月,美国农业部因“行业对扩大生产的持续谨慎态度”下调了对 2023 年整个鸡蛋生产的预测。

图表由巴塞尔·穆沙巴什制作。数据来源于 2019-2024 年美国农业部/NASS 鸡肉和鸡蛋报告。

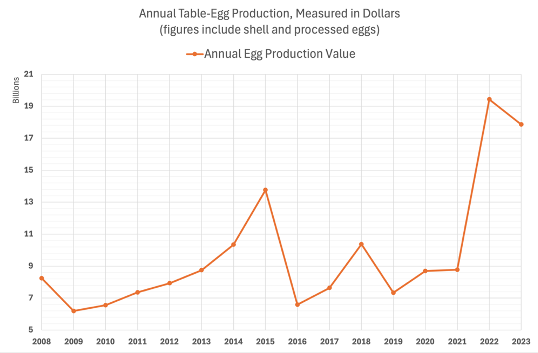

In other words, the only thing that the egg industry seems to have expanded in response to the avian flu epidemic is windfall profits — which have likely amounted to more than $15 billion since the epidemic began (judging by the increase in the value of annual egg production since 2022), and appear to have been spent primarily on stock buybacks, dividends, and acquisitions of rivals instead of rebuilding and expanding flocks. When an industry starts profiting more from *not* producing than from producing, it’s a sign that something isn’t right. It could be an innocent bottleneck. But when it lasts for three years on end with no relief in sight, it's usually a sign of something else that’s pervasive in America — monopolization.

换句话说,鸡蛋行业似乎在应对禽流感疫情时唯一扩大的就是暴利——自疫情开始以来,暴利可能已超过 150 亿美元(根据 2022 年以来年产蛋值的增长判断),而且这些收益主要用于股票回购、分红和收购竞争对手,而不是重建和扩展鸡群。当一个行业从*不*生产中获得的利润超过从生产中获得的利润时,这就表明存在某种不对劲的情况。这可能是一个无害的瓶颈。但当这种情况持续了三年之久且没有缓解的迹象时,这通常意味着美国普遍存在的另一种现象——垄断。

图表由 Basel Musharbash 制作。数据来源于 USDA/NASS QuickStats 数据库。

As the coming installments in this series will detail, the fundamental problem in the egg supply chain today is the simple fact that every industry involved in turning an egg into a chicken and turning a chicken into an egg—from the breeders and hatcheries that create the hens to the producers who use the hens to make eggs—has been hijacked by one or two financier-backed corporations, with the incentives flipped from competing entities seeking to produce more eggs to an oligopoly trying to restrain the production of eggs.

正如本系列接下来的几期将详细说明的那样,今天鸡蛋供应链中的根本问题在于一个简单的事实:从育种者和孵化场创造母鸡,到利用母鸡生产鸡蛋的生产者,整个过程中参与的每个行业都被一两个金融支持的公司劫持,激励机制从寻求生产更多鸡蛋的竞争实体转变为试图限制鸡蛋生产的寡头垄断。

On one end of the egg supply chain, you have two companies who control chicken genetics, the billionaire-owned Erich Wesjohann Group and the private-equity-backed Hendrix Genetics. Headquartered a short car trip apart in Cuxhaven, Germany, and Boxmeer, Netherlands, these private firms have systematically gained control over the supply of egg-laying hens to American producers over the past two decades by buying out or suppressing rivals and challengers. Today, no egg producer in this country can expand the number of hens in its flock — or even replace the hens it already has when they age out or die — without the cooperation of this duopoly. And, since the value of hens rises with the price of the eggs, when the price of eggs is high these two barons have a clear interest in keeping the supply of pullets to producers on a tight leash — so the high prices stick.

在蛋供应链的一端,有两家公司控制着鸡的基因,亿万富翁拥有的 Erich Wesjohann 集团和私募股权支持的 Hendrix Genetics。这些私人公司分别总部位于德国的 Cuxhaven 和荷兰的 Boxmeer,仅需短途车程。这些公司在过去二十年中通过收购或压制竞争对手,系统性地获得了对美国生产者蛋鸡供应的控制权。如今,在这个国家,没有任何蛋生产者能够扩展其鸡群数量——即使是更换已经老化或死亡的母鸡——而不依赖于这种双头垄断。并且,由于母鸡的价值随着鸡蛋价格的上涨而上升,当鸡蛋价格高时,这两位大亨显然有理由对生产者的雏鸡供应保持紧缩,以保持高价位。

On the other end of the egg supply chain, you have the largest egg producer in the country and the world, Cal-Maine Foods.

在鸡蛋供应链的另一端,您会看到全国和全球最大的鸡蛋生产商——加州缅因食品公司(Cal-Maine Foods)。

Cal-Maine isn’t just the largest egg producer and distributor, but has a range of coercive tools at its disposal to discipline smaller rivals in the industry. Through what looks like a special arrangement with the chicken-genetics barons, Cal-Maine can expand its output faster and cheaper than any other egg producer. If a producer gets out of line and responds to high prices with flock expansions or discounting practices that Cal-Maine doesn’t approve of, Cal-Maine can flood the market with eggs—depressing prices for everyone while capturing market share for itself. As a publicly-traded company with a low cost of capital from Wall Street, Cal-Maine can live with low egg prices for a long time. Not so for most of the 60 or so family-owned producers who make up the rest of the egg industry; they’re actual businesses that need to turn a profit.

Cal-Maine 不仅是最大的鸡蛋生产和分销商,还拥有一系列强制手段来对付行业内较小的竞争对手。通过与鸡基因大亨的特殊安排,Cal-Maine 能以更快、更便宜的速度扩大产量,超越任何其他鸡蛋生产商。如果某个生产商失去理智,因高价格而进行群体扩张或采取 Cal-Maine 不认可的折扣措施,Cal-Maine 可以通过大量涌入市场的鸡蛋来打压价格,进而为自己获取市场份额。作为一家上市公司,凭借华尔街较低的资本成本,Cal-Maine 可以长期忍受低鸡蛋价格。但对于其余约 60 家家族企业的生产商而言则不然;它们是需要盈利的实际企业。

The power wielded by these dominant firms — EW Group, Hendrix, and Cal-Maine — is not theoretical. Just last year, a federal jury found that, shortly after Cal-Maine rose to dominance in the late 1990s, its executives took over the leadership of a longstanding industry association called the United Egg Producers (UEP) and turned it into a cartel, the equivalent of what the presiding judge analogized to a “mob boss” for the industry.

这些主导公司的权力——EW Group、Hendrix 和 Cal-Maine——并非理论上的。就在去年,联邦陪审团发现,Cal-Maine 在 1990 年代末崛起后不久,其高管接管了一个名为美国蛋品生产商协会(United Egg Producers,UEP)的长期行业协会,并将其转变为一个卡特尔,总统法官将其比作该行业的“黑帮老大”。

Shortly after, other major egg producers that had long resisted joining the UEP — like Rose Acre Farms — gave up their independence and entered the UEP’s fold, until it finally represented producers accounting for more than 90% of the country’s egg supply. Cal-Maine’s executives then used the association as a “bullhorn” to “bark out orders” at egg producers and “coordinate a conspiracy” to restrict the supply of eggs in the United States through a variety of strategies — including throttling the replacement of hens lost to mortality and a fake “animal welfare” program designed to reduce overall flock numbers rather than improve hen’s lives.

不久之后,其他长期抵制加入 UEP 的主要蛋鸡生产商,如 Rose Acre Farms,放弃了独立,加入了 UEP,最终其代表的生产商占全国鸡蛋供应的 90%以上。Cal-Maine 的高管随后利用该协会作为“喇叭”,对蛋鸡生产商“发号施令”,并“协调阴谋”通过多种策略限制美国的鸡蛋供应——包括限制因死亡损失的母鸡的替换以及一个伪“动物福利”项目,旨在减少整体鸡群数量而不是改善母鸡的生活。

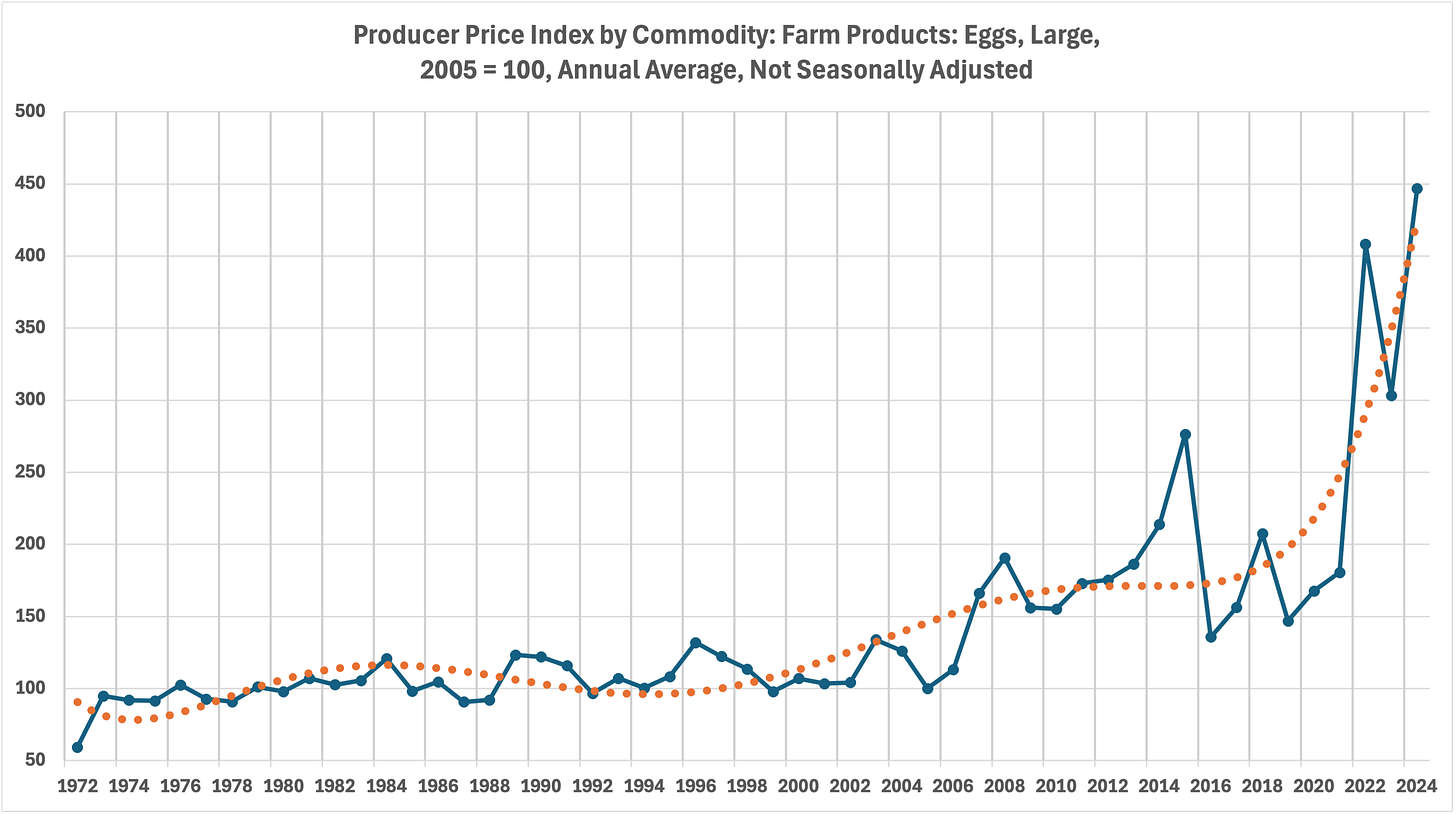

An economist who helped plan the UEP cartel summed up the economic rationale behind it pretty simply: “More hens, less income!” And the conspiracy’s results proved he was right. Wholesale egg prices reached unprecedented heights over the course of the 2000s and then never came back down — settling around a new, higher focal point 50 to 100 percent higher than the pre-conspiracy level for the next decade. Something similar could be happening with the current avian flu epidemic. Indeed, the new focal point appears to be already here: There was an argument that wholesale egg prices “collapsed” in 2023. In reality, they were on average 75% higher than wholesale egg prices before the epidemic’s onset in 2022.

一位帮助策划 UEP 卡特尔的经济学家简单总结了其经济合理性:“鸡越多,收入越少!”而这一阴谋的结果证明了他的正确性。在 2000 年代,批发鸡蛋价格达到了前所未有的高度,并且此后再也没有回落——在接下来的十年中,这些价格稳定在比阴谋发生前高出 50%到 100%的新高点。当前禽流感疫情也可能出现类似情况。事实上,新的高点似乎已经出现:曾有人认为 2023 年批发鸡蛋价格“崩溃”。实际上,它们的平均价格比 2022 年疫情爆发前的批发鸡蛋价格高出 75%。

图表由 Basel Musharbash 绘制。数据来自 FRED/劳工统计局。

One way to understand the problem of eggs is consistent with similar problems we’re seeing in other parts of the economy. From baby formula to cancer drugs to beef, shortages and supply shocks in concentrated industries are now routine.

理解鸡蛋问题的一种方式与我们在经济其他部分看到的类似问题是一致的。从婴儿配方奶粉到癌症药物再到牛肉,集中行业中的短缺和供应冲击现在已成为常态。

In other words, the current egg crisis is what the Sovietization of American business looks like. We don’t have egg companies in the business of making eggs anymore. We have egg companies in the business of exploiting egg shortages, almost a private government of eggs. This dynamic is so extreme that the Agriculture Secretary had to go on something of a diplomatic mission to Cal-Maine last month to try to sweet-talk its executives into loosening their grip on the egg supply — and walked out of her meeting saying the USDA is going to pay egg producers to rebuild the country’s hen flock at a time when rebuilding the hen flock is going to be more profitable for them than it has ever been.

换句话说,目前的蛋类危机就是美国商业苏维埃化的体现。我们不再有制造鸡蛋的蛋类公司。我们有的是利用鸡蛋短缺的蛋类公司,几乎是一个私营的蛋类政府。这个动态极端到农业部长上个月不得不进行某种外交使命,前往 Cal-Maine 试图劝说其高管放松对蛋类供应的控制——并在会议结束时表示,农业部将向蛋类生产商支付补贴,以重建国家的母鸡群,而在重建母鸡群的时机,对他们来说将比以往任何时候都更有利可图。

So, that’s the broad-brush picture. To understand how we got to this place where shortages are more profitable than production, we have to start with the origins of the American egg business. After all, there’s a reason that a big cheap breakfast served in a diner on the roadside was such a big part of American culture, and why it’s such a shock to see Denny’s levy an egg surcharge. So let’s start with how the big fluffy omelet became so Americana.

所以,这就是大致的情况。要理解我们是如何走到 shortages 比生产更有利可图的这个地步,我们必须从美国蛋业的起源开始。毕竟, roadside 的餐厅里提供一份便宜的丰盛早餐之所以成为美国文化的重要组成部分是有原因的,而 Denny’s 收取鸡蛋附加费更是令人震惊。那么,首先让我们来看看大型松软的蛋卷是如何成为美国风情的。

America as a Land of Egg Plenty

美国作为一个鸡蛋富饶之地

Producing an egg seems simple. An “old McDonald had a farm” kind of farmer breeds a lovely hen, grows it to adulthood, has it lay eggs, puts those eggs in a crate, and sends that crate to a grocery store in return for a negotiated price. And that’s basically how the industry worked until the middle of the 20th century. The essentials of that story remained on point, but the components were split up among a series of specialized operations.

生产一个鸡蛋似乎很简单。一个“老麦当劳有个农场”的农民培育了一只可爱的母鸡,让它长到成年,促使它下蛋,把那些蛋放在一个箱子里,然后将那个箱子送到杂货店,以换取协商好的价格。基本上,这就是该行业在 20 世纪中叶之前的运作方式。这个故事的要点仍然有效,但各个环节分拆为一系列专业化的操作。

If you abstract out what the egg farmer used to do all by himself, you get all the layers of the modern egg supply chain. First, as discussed above, there are breeders, who manage chicken genetics and produce “parent stock,” or the stock of birds that are mated to produce the fertilized eggs that become table-egg laying hens. Second, there are hatcheries, who buy parent stock from breeders, mate them to produce fertilized eggs, incubate their eggs to hatch table-egg laying chicks, and then grow the chicks into hens. Third, there are egg producers, who buy table-egg laying chicks or hens from the hatcheries and use them to produce eggs (some producers also buy fertilized eggs from hatcheries and incubate them in-house). Fourth, there are the various distributors and processors who buy eggs from producers. And finally, there are market reporters who survey buyers and sellers for information about egg prices and other market data points, and use that information to publish regular benchmarks for the market value of eggs.

如果将蛋农过去所有的工作抽象出来,就能得到现代蛋供应链的所有层级。首先,如上所述,有育种者,他们管理鸡的遗传基因,生产“亲本种”,即用于交配以产生变为食用蛋母鸡的受精蛋的鸟类。其次,有孵化场,他们从育种者那里购买亲本种,进行交配以产生受精蛋,孵化这些蛋以孵化出食用蛋小鸡,然后将小鸡养成母鸡。第三,有蛋生产者,他们从孵化场购买食用蛋小鸡或母鸡,用于生产鸡蛋(一些生产者也从孵化场购买受精蛋并在内部孵化)。第四,有各种分销商和加工商,他们从生产者那里购买鸡蛋。最后,还有市场报道员,他们对买家和卖家进行调查,获取有关鸡蛋价格和其他市场数据点的信息,并利用这些信息定期发布鸡蛋市场价值的基准。

So, to understand the story behind egg prices, we shouldn’t think about “the egg industry” or the “egg market” but a series of linked industries and markets — starting from the breeders and hatcheries, running through the egg producers and the egg buyers, all the way to the market reporters — the end result of which is the carton of eggs on the shelf. To get there, we have to start eighty years ago, when egg production was revolutionized by new technologies and techniques, and the modern egg supply chain was born.

因此,要理解鸡蛋价格背后的故事,我们不应仅关注“鸡蛋行业”或“鸡蛋市场”,而应该考虑一系列相互关联的行业和市场——从养殖者和孵化场开始,经过鸡蛋生产者和鸡蛋买家,最终到达市场记者——最终结果就是货架上的一盒鸡蛋。为了达成这一点,我们必须追溯到八十年前,当时新技术和新方法彻底改变了鸡蛋生产,现代鸡蛋供应链由此诞生。

In 1942, New Deal-era Secretary of Agriculture, and then Vice President, Henry A. Wallace built a new model for producing eggs. It was based on creating better birds through the “hybridization” of chicken, which is the crossing of two or more pure breeds of chicken to create a “hybrid” chicken with specific qualities. The resulting hens laid more or better eggs, required less feed, and were more adapted to specific production systems. After Wallace developed them, cross-breeding methods were shared with small breeders around the country through United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) extension offices at land grant colleges, which conducted basic research into the field and made breeding know-how and pure-bred stocks available to the public. Within a few years, dozens of other “primary breeders” emerged, creating a dynamic chicken genetics industry with many local and regional players.

1942 年,新政时期的农业部长,后来成为副总统的亨利·A·华莱士建立了一种新的鸡蛋生产模型。这个模型基于通过“杂交”来培育更优质的鸡,这意味着交配两种或更多的纯种鸡,以创造出具有特定品质的“杂交”鸡。最终产生的母鸡产蛋量更多或更优质,所需饲料更少,更适应特定的生产系统。在华莱士开发这些鸡后,杂交繁育的方法通过美国农业部(USDA)的土地拨款大学的推广办公室分享给全国的小型饲养者,这些办公室开展了该领域的基础研究,并将繁育技术和纯种种鸡的种子提供给公众。几年之内,出现了数十个其他“主要育种者”,形成了一个充满活力的鸡遗传学产业,拥有许多地方和地区参与者。

在 1940 年,FDR 任命亨利·A·华莱士为他的副总统。这张照片摄于 1940 年 7 月 19 日,期间举行了一场关于新政农业项目的白宫广播。

These primary breeders developed branded strains of layer chickens and marketed them to thousands of hatcheries nationwide. The hatcheries bought “parent stock” for branded strains of chicken from the primary breeders, mated them to produce fertilized eggs, incubated the eggs until they hatched, and then sold the resulting chicks and young hens (called “pullets”) to farmers, which raised them into mature hens and then used them to produce eggs. As farmers got to know the different hybrid chicken brands, they selected among them for productivity and other characteristics that suited their production systems — creating a virtuous feedback loop.

这些主要育种者开发了品牌化的蛋鸡品种,并将其销售给全国数千家孵化场。这些孵化场从主要育种者那里购买“亲本”鸡种,以生产品牌化的鸡,由此配对产生受精卵,孵化这些卵直到它们孵化成小鸡,然后将这些小鸡和年轻的母鸡(称为“雏鸡”)出售给农民,农民将它们养大成母鸡,进而用来生产鸡蛋。当农民逐渐了解不同的杂交鸡品牌时,他们根据生产效率和适合自身生产系统的其他特性进行选择,从而形成了一个良性反馈循环。

Soon, these developments led to a revolution in egg production both at home and around the world. The number of eggs laid per hen in the United States increased by almost 44% between 1940 and 1955 — more, in relative terms, than it would increase over the next four decades combined. Hybrid hens originating from the United States were soon introduced around the world, leading to a rapid expansion in global egg production—not to mention the explosion in cheap American diners dotting the new highway systems being built.

不久,这些发展引发了国内和全球鸡蛋生产的革命。1940 年至 1955 年间,美国每只母鸡产蛋数量增加了近 44%——相对而言,增幅超过了接下来四十年的总和。起源于美国的杂交母鸡很快在世界各地投入使用,导致全球鸡蛋生产迅速扩张——更不用说新建高速公路系统上到处涌现的廉价美式餐馆的爆炸式增长。

In tandem with the mid-century revolution in chicken breeding, there was a revolution in egg production systems. Poultry science departments at land-grant colleges engaged in continual field testing and production research to develop new equipment and systems for egg farmers, ultimately developing critical technologies like large-scale incubators to hatch eggs on a schedule, fine-sand blowers to clean eggs without breaking shells, and caged-rearing systems to mechanize feeding, watering, and egg-collection in their hen houses.

伴随着 20 世纪中叶鸡种繁育的革命,蛋生产系统也经历了一场革命。土地赠与大学的禽类科学系不断进行田野测试和生产研究,以为蛋农开发新设备和系统,最终研发出一些关键技术,如大型孵化器以按照计划孵化蛋、细砂吹风机以在不破壳的情况下清洁鸡蛋,以及笼养系统以机械化母鸡的喂养、饮水和收集鸡蛋。

Although these innovations gave rise to some efficiencies of scale at the farm level and enabled the rise of factory-style hatcheries and egg production facilities, the industry as a whole remained highly decentralized at every stage of production and distribution well into the late 1970s. As late as 1978, most producers were still small, and most egg production still took place on farms with fewer than 50,000 hens. There were just 34 “big” egg companies with 1 million or more egg-laying hens each, and they accounted for only 27% of annual egg production.

尽管这些创新在农场层面带来了一些规模效应,并推动了工厂式孵化场和蛋生产设施的兴起,但整个行业在生产和分配的每个阶段仍然高度分散,直到 1970 年代末。直到 1978 年,大多数生产者仍然是小型的,大多数蛋生产仍发生在拥有不到 50,000 只母鸡的农场上。只有 34 家“大型”蛋公司,每家至少有 100 万只蛋鸡,它们的年产蛋量仅占 27%。

Undergirding this system was law: Antitrust enforcement prevented the largest breeders, hatcheries, and egg producers from growing by serial acquisitions or by handicapping their rivals’ access to customers or suppliers. For similar reasons, the markets into which egg producers sold their eggs—packers, retailers, processors, wholesalers, and institutions—also remained open and competitive, offering a wide diversity of potential buyers to egg producers of various sizes in every region of the country.

支撑这一系统的是法律:反垄断执法阻止了最大养殖者、孵化场和蛋类生产商通过连环收购或限制竞争对手获取客户或供应商的途径来扩张。出于类似原因,蛋类生产商销售其鸡蛋的市场——包装商、零售商、加工商、批发商和机构——也保持开放和竞争,为各地区不同规模的蛋类生产商提供了多样化的潜在买家。

Because of the openness of the egg industry and the abundance of small producers with excess capacity, there was almost always a significant surplus of eggs in the country. When that surplus narrowed (whether because of long-term population growth or a sudden crisis, like an avian flu epidemic), elevated egg prices invited rapid expansions in egg output from new and existing producers that quickly brought prices back down. For example, during the avian flu epidemic of 1983-1984, producers had to cull tens of millions of layer hens and other birds, including nearly every chicken in Pennsylvania. But retail egg prices rose by just 66 percent over a few months — and promptly fell just as sharply over the next few months as producers quickly replaced the hens they’d lost.

由于蛋鸡产业的开放性和大量小型生产者的过剩产能,国内几乎总是存在显著的鸡蛋过剩。当这种过剩缩小时(无论是由于长期人口增长还是突发危机,如禽流感疫情),高企的鸡蛋价格吸引了新老生产者迅速扩大产量,从而迅速将价格拉回。举例来说,在 1983-1984 年禽流感疫情期间,生产者不得不扑杀数千万只蛋鸡和其他鸟类,包括宾夕法尼亚几乎所有的鸡。但零售鸡蛋价格在几个月内仅上涨了 66%,而在接下来的几个月中随着生产者迅速替换失去的母鸡,价格也一样迅速下跌。

“Eggs,” said a prominent agricultural economist in 1978, “will be processed and produced in this country if there is a fair return on investment. When the return [on eggs] becomes high,” he continued, “there will be expansion of production that will reduce prices.” And that was actually true: Higher prices routinely led farmers to get into the egg business to make money, and that in turn regularly reset the market with more supply. Price spikes were short-lived. Shortages were unheard of. America was a land of egg plenty.

“鸡蛋,”一位著名的农业经济学家在 1978 年说,“如果有合理的投资回报,这个国家将对鸡蛋进行加工和生产。当鸡蛋的回报变高时,”他继续说道,“生产将会扩大,从而降低价格。” 这实际上是正确的:更高的价格通常促使农民进入鸡蛋业务以赚钱,而这又会定期通过更多供应重新调整市场。价格飙升是短暂的。短缺是闻所未闻的。美国是一个鸡蛋丰饶的土地。

Then, everything changed.

然后,一切都改变了。

Stay tuned for part two of Hatching a Conspiracy, which will come next week. Hatching a Conspiracy is part of a new BIG project where we do deep investigative journalism on specific industries. If you’d like to support this work, sign up as a paid subscriber for BIG, or if you are already a paid subscriber, give a subscription to someone who you think would like it.

请保持关注《策划阴谋》的第二部分,预计将于下周发布。《策划阴谋》是一个新 BIG 项目的一部分,我们将在特定行业进行深入的调查性报道。如果您想支持这项工作,请注册成为 BIG 的付费订阅者,或者如果您已经是付费订阅者,请送一个订阅给您认为会喜欢的人。

Except where otherwise noted or linked, all statistical figures in Hatching a Conspiracy were derived by Basel Musharbash from analysis of data compiled from the USDA National Agricultural Statistics Service’s QuickStats database, Chicken and Eggs reports, and Hatchery Production Annual Summary reports, among others, as well as the USDA Economic Research Service’s international trade data hub.

除非另有说明或链接,否则《孵化阴谋》中的所有统计数字均由 Basel Musharbash 通过分析来自美国农业部国家农业统计服务局的 QuickStats 数据库、鸡蛋报告和孵化生产年度总结报告等的数据得出,以及美国农业部经济研究服务局的国际贸易数据中心。

Subscribe to BIG by Matt Stoller

订阅 Matt Stoller 的 BIG

数千名付费订阅者

垄断权力的历史和政治。

Mr. Musharbash, I had reluctantly cancelled my subscription to BIG in a “cull out most of my subscriptions” move and was living out the remaining days of my last payment. THIS post has moved me to renew and I gratefully thank you for writing it. I dare not miss Part 2 and will simply have to cut something else that compares poorly to the excellent reporting you’re providing. You have my everlasting appreciation.

穆沙巴什先生,我之前迫不得已取消了我的 BIG 订阅,这是“精简我的大部分订阅”的一部分,而我正度过我最后付款的剩余日子。这篇文章让我感动,促使我重新订阅,我非常感谢您写下这篇文章。我不敢错过第二部分,只能舍弃一些在您出色的报道面前显得不够优秀的东西。您将永远获得我的感激。

Banger! I love it when Basel writes for the newsletter. Share with family and friends folks

太棒了!我喜欢巴塞尔为通讯写稿的时候。大家和家人朋友分享吧!