Abstract 抽象的

Cerebral vasculitis is a rare cause of juvenile stroke. It may occur as primary angiitis of the central nervous system (PACNS) or as CNS manifestation in the setting of systemic vasculitis. Clinical hints for vasculitis are headache, stroke, seizures, encephalopathy and signs of a systemic inflammatory disorder. Diagnostic work-up includes anamnesis, whole body examination, laboratory and cerebral spinal fluid (CSF) studies, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), angiography and brain biopsy. Due to the rarity of the disease, exclusion of more frequent differential diagnoses is a key element of diagnostic work-up. This review summarizes the steps that lead to the diagnosis of cerebral vasculitis and describes the red flags and pitfalls. Despite considering the dilemma of angiography-negative vasculitis and false-negative brain biopsy in some cases, it is important to protect patients from ‘blind’ immunosuppressive therapy in unrecognized non-inflammatory differential diagnosis.

腦血管炎是青少年中風的罕見原因。它可能作為中樞神經系統原發性血管炎 (PACNS) 或系統性血管炎中的 CNS 表現而發生。血管炎的臨床提示包括頭痛、中風、癲癇發作、腦病變和全身性發炎疾病的徵兆。診斷檢查包括病史、全身檢查、實驗室和腦脊髓液 (CSF) 研究、磁振造影 (MRI)、血管攝影和腦部活檢。由於疾病的罕見性,排除更常見的鑑別診斷是診斷檢查的關鍵要素。這篇綜述總結了腦血管炎診斷的步驟,並描述了危險信號和陷阱。儘管考慮到某些病例中血管造影陰性血管炎和假陰性腦部活檢的困境,但在未識別的非發炎鑑別診斷中保護患者免受「盲目」免疫抑制治療很重要。

Keywords: encephalitis, granulomatosis with polyangiitis, stroke, vasculitis

關鍵字:腦炎,肉芽腫性多血管炎,中風,血管炎

Other Articles published in this series.

本系列發表的其他文章。

Paraneoplastic neurological syndromes. Clinical and Experimental Immunology 2014, 175: 336–48.

副腫瘤性神經系統綜合症。臨床和實驗免疫學 2014 年,175:336–48。

Diagnosis, pathogenesis and treatment of myositis: recent advances. Clinical and Experimental Immunology 2014, 175: 349–58.

肌炎的診斷、發病機制和治療:最新進展。臨床和實驗免疫學 2014 年,175:349–58。

Disease-modifying therapy in multiple sclerosis and chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyradiculoneuropathy: common and divergent current and future strategies. Clinical and Experimental Immunology 2014, 175: 359–72.

多發性硬化症和慢性發炎性脫髓鞘性多發性神經根神經病變的疾病修飾治療:目前和未來常見和不同的策略。臨床和實驗免疫學 2014 年,175:359–72。

Monoclonal antibodies in treatment of multiple sclerosis. Clinical and Experimental Immunology 2014, 175: 373–84.

單株抗體治療多發性硬化症。臨床和實驗免疫學 2014 年,175:373–84。

CLIPPERS: chronic lymphocytic inflammation with pontine perivascular enhancement responsive to steroids. Review of an increasingly recognized entity within the spectrum of inflammatory central nervous system disorders. Clinical and Experimental Immunology 2014, 175: 385–96.

CLIPPERS:慢性淋巴球炎症,伴隨對類固醇有反應的腦橋血管周圍增強。回顧發炎性中樞神經系統疾病範圍內日益被認可的實體。臨床和實驗免疫學 2014 年,175:385–96。

Requirement for safety monitoring for approved multiple sclerosis therapies: an overview. Clinical and Experimental Immunology 2014, 175: 397–407.

已批准的多發性硬化症療法的安全監測要求:概述。臨床和實驗免疫學 2014 年,175:397–407。

Myasthenia gravis: an update for the clinician. Clinical and Experimental Immunology 2014, 175: 408–18.

重症肌無力:臨床醫師的最新情況。臨床和實驗免疫學 2014 年,175:408–18。

Multiple sclerosis treatment and infectious issues: update 2013. Clinical and Experimental Immunology 2014, 175: 425–38.

多發性硬化症治療和感染問題:2013 年更新。

Introduction 介紹

Cerebral angiitis is a rare cause of stroke, headache, encephalopathy and seizures. Frequently, multi-locular lesions on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), inflammatory laboratory findings in stroke patients or intracranial stenoses detected in computed tomography angiography (CTA), MRA or angiography raise the suspicion of this diagnosis [1], but none of these findings is reliable enough to allow a definite diagnosis of cerebral vasculitis [1,2]. Traditionally, the terms vasculitis, arteritis and angiitis are used simultaneously, but are interchangeable with each other.

腦血管炎是中風、頭痛、腦病變和癲癇發作的罕見原因。通常,磁振造影(MRI) 上的多房性病變、中風患者的發炎實驗室檢查結果或電腦斷層血管攝影(CTA)、MRA 或血管攝影中檢測到的顱內狹窄會引起對此診斷的懷疑。 1 ],但這些發現都不夠可靠,不足以明確診斷腦血管炎[ 1 , 2 ]。傳統上,術語血管炎、動脈炎和血管炎同時使用,但可以互換。

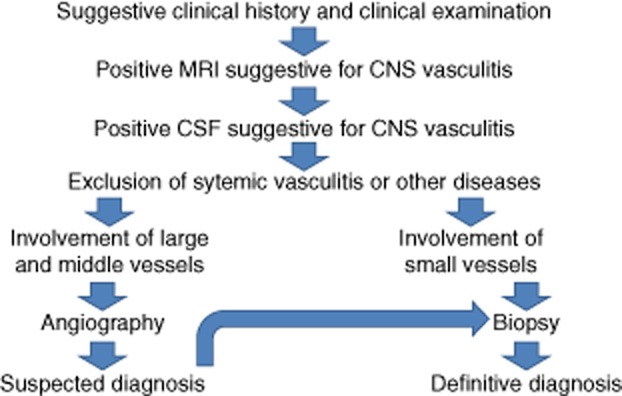

What are the steps in order to establish the diagnosis (Fig. 1)?

確定診斷需要採取哪些步驟(圖 1)。 1 )?

Figure 1. 圖 1.

Flowchart on the diagnostic work-up for cerebral vasculitis.

腦血管炎診斷檢查流程圖。

Reliable clinical suspicion

可靠的臨床懷疑

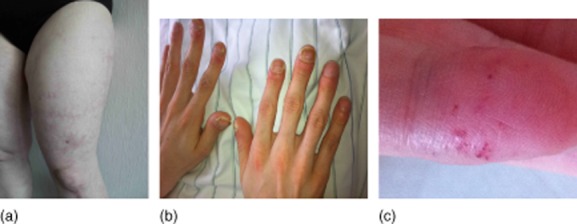

The first and most important step in the diagnostic work-up is detailed anamnesis and clinical examination, including asking for drug abuse, former medical conditions, characterization of symptoms, especially headaches [3–5], and family medical history. Medical examination should focus on skin or other systemic signs for rheumatic or non-inflammatory diseases (Fig. 2) [6–8].

診斷檢查的第一步也是最重要的一步是詳細的病史和臨床檢查,包括詢問是否濫用藥物、先前醫療狀況、症狀特徵,尤其是頭痛。 3 – 5 ],以及家族病史。身體檢查應著重於皮膚或其他全身體徵是否有風濕性或非發炎性疾病(圖 1)。 2 )[ 6 – 8 ]。

Figure 2. 圖 2.

Clinical signs of vasculitis mimics: (a) livedo racemosa in Sneddon's syndrome; (b) juvenile stroke with pulmonary AV-shunts: Morbus Osler; (c) angioceratoma in Fabry's disease.

血管炎的臨床症狀類似於:(a) Sneddon 症候群中的總狀青斑; (b) 患有肺房室分流術的青少年中風:Morbus Osler; (c) 法布瑞氏症的血管角化瘤。

Patients presenting with multi-focal symptoms accompanied by headache, psychiatric symptoms and signs of a systemic inflammatory disorder need a diagnostic work-up in order to exclude or detect cerebral angiitis [9–12]. In particular, younger stroke patients without classical vascular risk factors, patients with clinical signs of a rheumatic disease, i.e. arthritis, Raynaud phenomenon, red eye, lung or kidney affection, and those with inflammatory laboratory findings [high erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), C-reactive protein (CRP), anaemia or cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) pleocytosis] may suffer from an angiitis [13]. The combination of neurological symptoms and signs of a systemic disease need an extensive diagnostic work-up [9,11,14].

出現多灶性症狀並伴隨頭痛、精神症狀和全身性發炎疾病徵象的患者需要進行診斷檢查,以排除或檢測腦血管炎。 9 – 12 ]。特別是,沒有典型血管危險因子的年輕中風患者,有風濕病臨床症狀的患者,即關節炎、雷諾氏現象、紅眼、肺部或腎臟病變,以及有發炎實驗室檢查結果的患者[紅血球沉降速率( ESR)高, C反應蛋白(CRP)、貧血或腦脊髓液(CSF)細胞增多]可能患有血管炎[ 13 ]。神經系統症狀和全身性疾病徵象的結合需要進行廣泛的診斷檢查。 9 , 11 , 14 ]。

First diagnostic steps in suspected cerebral vasculitis

All patients need a laboratory work-up focusing on inflammation and antibody-mediated diseases [9,15]. Raised acute phase proteins (high ESR, CRP), hypochromic anaemia and low complement are typical findings in the systemic vasculitides. Depending on the underlying condition, anti-neutrophil cytospasmic antibodies (ANCA) or anti-nuclear antibodies (ANA) are detected with high titres [15]. The typical picture in the CSF is a mild lymphocytic pleocytosis combined with an elevated protein level. Oligoclonal banding may occur temporarily [16].

In order to detect a cerebral vasculitis, MRI studies, including diffusion, gradient echo and contrast enhanced T1 sequences, are necessary [9,17,18]. Frequently, both new and older ischaemic lesions are detected; the combination of ischaemic and haemorrhagic lesions is not uncommon. Diffuse white matter lesions suggestive for microangiopathies are frequently observed. Prominent gadolinium-enhancement of the leptomeninges is rare [19,20]. Gadolinium-enhanced intracerebral lesions are observed in about one-third of patients [16].

Special techniques such as ‘Black Blood MRI’ [21], contrast-enhanced vessel MRI or positron emission tomography (PET) imaging may be helpful in order to visualize the inflammation of the vessel wall directly [18,22]. While these techniques have been studied extensively in the variants of giant cell arteritis (GCA) [23,24], data for the other vasculitides are sparse. In the cranial variant of GCA, ultrasound studies with duplex sonography demonstrating the halo sign are highly sensitive and specific [25].

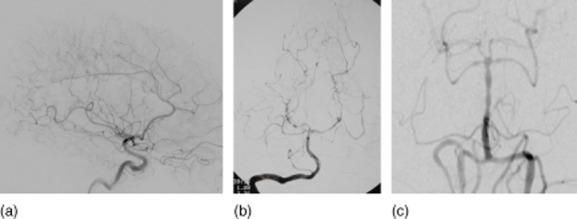

Despite suggestive MRA or CTA, conventional angiography is often mandatory (Fig. 3). Alternating areas of narrowing and dilatation or multi-locular occlusions of intracranial vessels are highly suggestive of vasculitis. However, it should be considered that the ‘typical’ suspicion of vasculitis in angiography is often caused by differential diagnoses such as reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndrome (RCVS) or other non-inflammatory diseases [4]. Moreover, small-vessel vasculitis is associated typically with negative cerebral angiography [26,27].

Figure 3.

Angiographic findings in vasculitis mimics: (a) Divry–van Bogaert syndrome; (b) bacterial endocarditis (see Berlit [1]); (c) reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndrome (see Kraemer and Berlit [16]).

In the case of CNS affection in systemic biopsy-proven vasculitis additional brain biopsy is often expendable; however, exclusion of other causes of neurological symptoms such as progressive multi-focal leucencephalopathy or medication side effects is extremely important [28,29].

Diagnosis of definitive vasculitis

Once the tentative diagnosis of cerebral angiitis is established, it must be clarified if the patient suffers from the manifestation of a systemic disease, or whether a primary angiitis of the CNS (PACNS) is the underlying pathology [9,30].

The diagnostic criteria [15] for PACNS include acquired neurological symptoms or findings not explained after a thorough diagnostic assessment, a cerebral angiography demonstrating the features of vasculitis and a CNS biopsy sample demonstrating angiitis [10,16]. Any other disorder including the systemic vasculitides to which the angiographic or pathological features might be secondary must be excluded [30].

PACNS is an uncommon disease in which lesions are limited to the brain and spinal cord. The condition is very rare, with an estimated incidence from 2·4:1 million to fewer than 1:2 million [31]. Since the first histological description in 1922, approximately 500 cases have been published worldwide [31]. Recently, a working group from the Mayo Clinic published a series of 101 patients with PACNS seen over two decades from 1983 to 2003 [10]. We identified 21 patients treated at Alfried Krupp Hospital, Essen, Germany between 2003 and 2008 with a diagnosis of definite PACNS [16]. The most frequent clinical presentations are cerebral ischaemia (75%), headache (60%) and altered cognition (50%) [8,16]. Intracranial haemorrhage is infrequent.

Almost all patients show MRI abnormalities. Ischaemic infarctions with diffusion disturbances are seen in 75%; signs of microangiopathy are present in 65%. Gadolinium-enhanced lesions are detected more frequently with amnestic syndromes at disease onset and with gait disturbances. MR-angiography (MRA) is suggestive of vasculitis in 45% [22]. MRI of PACNS may be suspicious for brain tumour, and PACNS mimicking tumour-like lesions is often diagnosed by biopsy by chance [32]. Conventional cerebral angiography is indicative of vasculitis in up to 75% if performed repeatedly [1,8,11,31].

CSF examinations disclose abnormal findings (cell count >5 cells/μl or total protein concentration >45 mg/dl) in the majority of patients [15]. Oligoclonal banding is found occasionally. Besides possible high CRP, serum screening is unremarkable for complement factors, ANA, ANCA or bacterial or viral antibodies. Although a large-scale ‘laboratory screen’ for autoimmune or infectious diseases is essential to exclude treatable differential diagnoses, one should be prepared for occasional ‘positive’ results.

Brain biopsy represents the gold standard in establishing the diagnosis in PACNS [9,16,26,33–35]. In PACNS, CNS biopsy specimens should be obtained in MRI-or angiographically involved areas [15]. Histopathological examination reveals a definite diagnosis of PACNS in approximately 60% of patients [8]. The ideal diagnostic brain biopsy is a 1-cm3 brain tissue with both grey and white matter as well as leptomeninges, and preferably a cortical vessel. The rate of false-negative brain biopsies is explained by the segmental involvement of vessels and a possible mismatch between radiological abnormalities and histological predominant lesions [8]. The morbidity rate of brain biopsy (0·03–2%) is definitely lower than the risks of unnecessary immunosuppressive treatments [8].

It is apparent that angiography and biopsy do not provide the same information in all patients [8]. Histology showed PACNS in 62% of Salvarini's patients who underwent biopsy [10]. Despite the fact that angiography has become the most frequent method of diagnosing PACNS, brain biopsy remains the gold standard [26]. It is important to realize that a negative biopsy certainly does not rule out the condition, and it should be considered as an attempt to establish the diagnosis and exclude other conditions [15]. A prospective multi-centre collaborative study collecting patients suspected to have cerebral vasculitis is needed urgently in order to establish standardized diagnostic and therapeutic procedures [1,9].

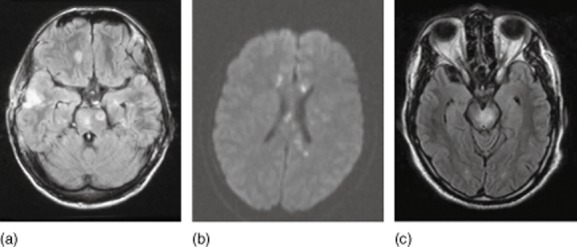

Behçet's disease is a multi-system, chronic-relapsing vasculitis affecting predominantly the venous system [8,30]. This rare disorder is more prevalent in Turkish patients and patients from the Far East. For oculo-mucocutaneous disease, the diagnostic criteria of the International Study Group for Behçet's disease include recurrent oral ulcerations with at least two of the following: recurrent genital ulceration, eye lesions (uveitis, cells in the vitreous on slit-lamp examination or retinal vasculitis), skin lesions (erythema nodosum) or a positive pathergy test result [8,15,36]. CNS manifestations (neuro-Behçet) occur in about 30% of patients after an average of 5 years [8,15,36]. Of these, 80% present parenchymal neuro-Behçet with frequent brainstem involvement (Fig. 4) [37]. Often, neuro-Behçet resembles multiple sclerosis [36].

Figure 4.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) findings in vasculitis mimics: (a) bacterial vasculitis (see Berlit [1]); (b) Susac syndrome; (c) neuro-Behçet.

Twenty per cent of patients with neuro-Behçet present with intracranial sinus or venous thrombosis with pseudotumour cerebri. In Behçet disease skin or brain biopsy is often expendable; however, exclusion of other causes of neurological symptoms is important [15,38].

Systemic large vessel vasculitides include Takayasu arteritis (age <50 years) and giant cell arteritis (GCA) or cranial arteritis (age >50 years) [15,30,33]. In GCA, the involvement of CNS arteries is very rare (<2%) [15].

Medium-sized vessels are affected in classical polyarteritis nodosa and the Kawasaki disease of childhood [11,30,33,39]. In classical polyarteritis nodosa, CNS involvement with headaches and encephalopathy is known in up to 20% [15].

The small vessel vasculitides are separated into immune complex-mediated [cryoglobulinaemic, immunoglobulin (Ig)A-associated, hypocomplementaemic anti-C1q] and ANCA-associated variants (microscopic polyangiitis, granulomatosis with polyangiitis Wegener and eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis Churg–Strauss) [11,30,33,39]. In these small vessel vasculitides, involvement of the peripheral nervous system is more common [15,40]; CNS involvement is rare (10% in granulomatosis with polyangiitis Wegener [15,41], 15% in eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis Churg–Strauss [15,42]).

Exclusion of differential diagnoses (Table 1)

Table 1.

Mimics of cerebral vasculitis and primary angiitis of the central nervous system (PACNS) (adapted from Birnbaum and Hellmann [9])

| Non-inflammatory vasculopathies |

| RVCS |

| Atherosclerosis |

| Neurofibromatosis |

| Fibromuscular dysplasia |

| CADASIL |

| MELAS |

| Sneddon's syndrome |

| Divry–van Bogaert syndrome |

| Moyamoya angiopathy |

| Osler's disease |

| Hypercoagulable state |

| Infections |

| Emboli from subacute bacterial endocarditis |

| Basilar meningitis caused by tuberculosis or fungal infection |

| Bacterial infections |

| Parainfectious syndromes (e.g. ADEM) |

| Susac syndrome |

| Demyelinating syndromes |

| Multiple sclerosis |

| NMO |

| Metabolic diseases |

| Fabry's disease |

| Systemic autoimmune (and rheumatic) diseases |

| Sarcoidosis |

| Neurolupus |

| Behçet |

| CNS manifestations as part of a primary systemic vasculitis |

| Large-vessel vasculitis |

| Giant-cell arteritis |

| Takayasu arteritis |

| Medium-vessel vasculitis |

| Polyarteritis nodosa |

| Kawasaki disease |

| Small-vessel vasculitis |

| ANCA-associated vasculitides (e.g. granulomatosis with polyangiitis, eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis, microscopic polyangiitis) |

| Immune-complex deposition (e.g. Henoch–Schönlein purpura, cryoglobulinaemia) |

| Rheumatic syndromes (e.g. lupus, Sjögren syndrome, scleroderma) |

| Malignant diseases |

| Primary CNS lymphoma |

| Lymphomatoid granulomatosis |

| Carcinomatous meningitis |

RVCS: reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndrome; CADASIL: cerebral autosomal dominant arteriopathy with subcortical infarcts and leucoencephalopathy; MELAS: mitochondrial encephalomyopathy, lactic acidosis and stroke-like episodes; ADEM: acute disseminated encephalomyelitis; NMO: neuromyelitis optica; ANCA: anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies.

Important differential diagnoses include RCVS [5,22,43,44], intracranial atherosclerosis [45], Moyamoya disease, autoimmune encephalopathies and infectious disorders such as varicella zoster virus (VZV) vasculopathies or endocarditis [29]. As the majority of these diseases resemble the MRI, digital subtraction angiography (DSA) and laboratory findings of angiitis, a biopsy of affected tissue is often necessary in order to prove the correct diagnosis. In systemic angiitis, biopsy may be performed from affected organs such as kidney, upper airways, muscle or peripheral nerves [46]. For PACNS, a cerebral and meningeal biopsy is the gold standard for diagnosis. Moreover, detailed anamnesis and diagnostic work-up often allow diagnosis of non-inflammatory vasculopathies such as Moyamoya disease [47], Fabry's disease [48–50], Sneddon's syndrome [6] and RCVS [22,43,51,52]. The most important differential diagnosis to CNS vasculitis is RCVS, which is characterized by thunderclap headache, watershed cerebral ischaemia, cortical subarachnoidal haemorrhages and angiography suggestive for ‘vasculitis’ (Table 2). However, RCVS is reversible within 12 weeks and is a non-inflammatory disease which should be treated by nimodipine. The misdiagnosis as CNS vasculitis with aggressive immunosuppressive treatment would be fatal.

Table 2.

Differential diagnosis between primary angiitis of the central nervous system (PACNS) and reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndrome (RCVS) (adapted from Calabrese et al. 2007 [31])

| RCVS | PCNSV | |

|---|---|---|

| Feature | Recurrent thunderclap headache | Insidious, chronic headache |

| Infarct pattern | ‘Watershed’ | Small, scattered |

| Lobar haemorrhage | Common | Very rare |

| Cortical SAH | Common | Very rare |

| Reversible oedema | Common | Possible |

| Angiography | ‘Sausage on a strine’ sign | Irregular, notched, ectasia |

SAH: subarachnoid haemorrhage.

In Fabry disease, recurrent strokes are sometimes associated with mild CSF pleocytosis and with systemic signs of inflammation, and a misdiagnosis as rheumatic disease or vasculitis is quite common [50]. Unfortunately, Moyamoya disease is also often misdiagnosed as vasculitis, although a Moyamoya pattern in angiography due to vasculitis is very uncommon [34]. A livedo racemosa in patients with cryptogenic stroke should lead to a detailed diagnostic work-up in order to differentiate inflammatory (polyarteritis nodosa, systemic lupus erythemadosus) from non-inflammatory vasopathies (Sneddon syndrome, Divry–van Bogaert syndrome, migraine) [6].

Acknowledgments

Many thanks to Thomas Pfefferkorn MD, Ingolstadt, Germany for providing the flowchart on the diagnostic work-up in suspected vasculitis (Fig. 1).

Disclosure

PB has received travel expenses and honoraria for lectures and/or educational activities from Bayer, Behring, Biogen Idec, Merck Serono, MSD, Novartis and Teva Pharmaceutical Industries.

MK has received travel expenses and honoraria for lectures and/or educational activities from Bayer, Biogen Idec, Merck Serono, Novartis, Shire Germany and Teva Pharmaceutical Industries.

Nevertheless, the review is not influenced by commercial interests.

References

- 1.Berlit P. Primary angiitis of the CNS – an enigma that needs world-wide efforts to be solved. Eur J Neurol. 2009;16:10–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2008.02348.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Neel A, Auffray-Calvier E, Guillon B, et al. Challenging the diagnosis of primary angiitis of the central nervous system: a single-center retrospective study. J Rheumatol. 2012;39:1026–1034. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.110707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lopez JI, Holdridge A, Chalela J. Headache and vasculitis. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2013;17:320. doi: 10.1007/s11916-012-0320-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kramer M, Berlit P. [Reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndrome vs cerebral vasculitis? On the importance and difficulty of differentiating] Nervenarzt. 2011;82:500–505. doi: 10.1007/s00115-010-3189-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Singhal AB, Hajj-Ali RA, Topcuoglu MA, et al. Reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndromes: analysis of 139 cases. Arch Neurol. 2011;68:1005–1012. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2011.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kraemer M, Linden D, Berlit P. The spectrum of differential diagnosis in neurological patients with livedo reticularis and livedo racemosa. A literature review. J Neurol. 2005;252:1155–1166. doi: 10.1007/s00415-005-0967-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sivley MD. Fabry disease: a review of ophthalmic and systemic manifestations. Optom Vis Sci. 2013;90:e63–78. doi: 10.1097/OPX.0b013e31827ec7eb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Berlit P. Diagnosis and treatment of cerebral vasculitis. Ther Adv Neurol Disord. 2010;3:29–42. doi: 10.1177/1756285609347123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Birnbaum J, Hellmann DB. Primary angiitis of the central nervous system. Arch Neurol. 2009;66:704–709. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2009.76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Salvarani C, Brown RD, Jr, Calamia KT, et al. Primary central nervous system vasculitis: analysis of 101 patients. Ann Neurol. 2007;62:442–451. doi: 10.1002/ana.21226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Twilt M, Benseler SM. The spectrum of CNS vasculitis in children and adults. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2012;8:97–107. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2011.197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Berlit P. Neuropsychiatric disease in collagen vascular diseases and vasculitis. J Neurol. 2007;254(Suppl. 2):II87–89. doi: 10.1007/s00415-007-2021-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Benseler S, Schneider R. Central nervous system vasculitis in children. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2004;16:43–50. doi: 10.1097/00002281-200401000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Neel A, Pagnoux C. Primary angiitis of the central nervous system. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2009;27:S95–107. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Berlit P, Kraemer M, Baumgaertel M, Diener HC, Weimar C, Berlit P, et al. Leitlinien der Deutschen Gesellschaft für Neurologie. Stuttgart: Thieme; 2012. Leitlinie Zerebrale Vaskulitis; pp. 406–427. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kraemer M, Berlit P. Primary central nervous system vasculitis: clinical experiences with 21 new European cases. Rheumatol Int. 2011;31:463–472. doi: 10.1007/s00296-009-1312-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Scolding N. Can diffusion-weighted imaging improve the diagnosis of CNS vasculitis? Nat Clin Pract Neurol. 2007;3:608–609. doi: 10.1038/ncpneuro0614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zuccoli G, Pipitone N, Haldipur A, Brown RD, Jr, Hunder G, Salvarani C. Imaging findings in primary central nervous system vasculitis. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2011;29:S104–109. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Salvarani C, Brown RD, Jr, Calamia KT, et al. Primary central nervous system vasculitis with prominent leptomeningeal enhancement: a subset with a benign outcome. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58:595–603. doi: 10.1002/art.23300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Salvarani C, Brown RD, Jr, Huston J, III, Hunder GG. Prominent perivascular enhancement in primary central nervous system vasculitis. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2008;26:S111. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pfefferkorn T, Linn J, Habs M, et al. Black blood MRI in suspected large artery primary angiitis of the central nervous system. J Neuroimaging. 2012;23:379–383. doi: 10.1111/j.1552-6569.2012.00743.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mandell DM, Matouk CC, Farb RI, et al. Vessel wall MRI to differentiate between reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndrome and central nervous system vasculitis: preliminary results. Stroke. 2012;43:860–862. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.111.626184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pfefferkorn T, Schuller U, Cyran C, et al. Giant cell arteritis of the basal cerebral arteries: correlation of MRI, DSA, and histopathology. Neurology. 2010;74:1651–1653. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181df0a09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Saam T, Habs M, Cyran CC, et al. [New aspects of MRI for diagnostics of large vessel vasculitis and primary angiitis of the central nervous system] Radiologe. 2010;50:861–871. doi: 10.1007/s00117-010-2004-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kraemer M, Metz A, Herold M, Venker C, Berlit P. Reduction in jaw opening: a neglected symptom of giant cell arteritis. Rheumatol Int. 2010;31:1521–1523. doi: 10.1007/s00296-010-1690-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Salvarani C, Brown RD, Jr, Calamia KT, et al. Angiography-negative primary central nervous system vasculitis: a syndrome involving small cerebral vessels. Medicine (Balt) 2008;87:264–271. doi: 10.1097/MD.0b013e31818896e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Benseler SM, deVeber G, Hawkins C, et al. Angiography-negative primary central nervous system vasculitis in children: a newly recognized inflammatory central nervous system disease. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52:2159–2167. doi: 10.1002/art.21144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Calabrese LH, Molloy ES. Therapy: rituximab and PML risk-informed decisions needed! Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2009;5:528–529. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2009.193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Berlit P. Isolated angiitis of the CNS and bacterial endocarditis: similarities and differences. J Neurol. 2009;256:792–795. doi: 10.1007/s00415-009-5018-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jennette JC, Falk RJ, Bacon PA, et al. 2012 revised International Chapel Hill Consensus Conference Nomenclature of Vasculitides. Arthritis Rheum. 2013;65:1–11. doi: 10.1002/art.37715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Calabrese LH, Dodick DW, Schwedt TJ, Singhal AB. Narrative review: reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndromes. Ann Intern Med. 2007;146:34–44. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-146-1-200701020-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tanei T, Nakahara N, Takebayashi S, Ito M, Hashizume Y, Wakabayashi T. Primary angiitis of the central nervous system mimicking tumor-like lesion – case report. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo) 2011;51:56–59. doi: 10.2176/nmc.51.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kraemer M, Berlit P. Systemic, secondary and infectious causes for cerebral vasculitis: clinical experience with 16 new European cases. Rheumatol Int. 2010;30:1471–1476. doi: 10.1007/s00296-009-1172-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kraemer M, Berlit P. Primary central nervous system vasculitis and Moyamoya disease: similarities and differences. J Neurol. 2010;257:816–819. doi: 10.1007/s00415-009-5425-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Elbers J, Halliday W, Hawkins C, Hutchinson C, Benseler SM. Brain biopsy in children with primary small-vessel central nervous system vasculitis. Ann Neurol. 2010;68:602–610. doi: 10.1002/ana.22075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Coban O, Bahar S, Akman-Demir G, et al. Masked assessment of MRI findings: is it possible to differentiate neuro-Behçet's disease from other central nervous system diseases? [corrected] Neuroradiology. 1999;41:255–260. doi: 10.1007/s002340050742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mirsattari SM, McGinn GJ, Halliday WC. Neuro-Behçet disease with predominant involvement of the brainstem. Neurology. 2004;63:382–384. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000130192.12100.8d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Joseph FG, Scolding NJ. Neuro-Behçet's disease in Caucasians: a study of 22 patients. Eur J Neurol. 2007;14:174–180. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2006.01613.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cantez S, Benseler SM. Childhood CNS vasculitis: a treatable cause of new neurological deficit in children. Nat Clin Pract Rheumatol. 2008;4:460–461. doi: 10.1038/ncprheum0860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Steidl C, Baumgaertel MW, Neuen-Jacob E, Berlit P. Vasculitic multiplex mononeuritis: polyarteritis nodosa versus cryoglobulinemic vasculitis. Rheumatol Int. 2010;32:2543–2546. doi: 10.1007/s00296-010-1447-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.deGroot K, Adu D, Savage CO. The value of pulse cyclophosphamide in ANCA-associated vasculitis: meta-analysis and critical review. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2001;16:2018–2027. doi: 10.1093/ndt/16.10.2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sable-Fourtassou R, Cohen P, Mahr A, et al. Antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies and the Churg–Strauss syndrome. Ann Intern Med. 2005;143:632–638. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-143-9-200511010-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ducros A, Boukobza M, Porcher R, Sarov M, Valade D, Bousser MG. The clinical and radiological spectrum of reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndrome. A prospective series of 67 patients. Brain. 2007;130:3091–3101. doi: 10.1093/brain/awm256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ducros A. Reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndrome. Lancet Neurol. 2012;11:906–917. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(12)70135-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kis B, Liebig T, Berlit P. Severe supraaortal atherosclerotic disease resembling Takayasu's arteritis. Vasc Health Risk Manag. 2007;3:351–354. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Berlit P. The spectrum of vasculopathies in the differential diagnosis of vasculitis. Semin Neurol. 1994;14:370–379. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1041097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kraemer M, Heienbrok W, Berlit P. Moyamoya disease in Europeans. Stroke. 2008;39:3193–3200. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.513408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dubuc V, Moore DF, Gioia LC, Saposnik G, Selchen D, Lanthier S. Prevalence of fabry disease in young patients with cryptogenic ischemic stroke. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2012.10.005. pii: S1052-3057(12)00337-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Marquardt L, Baker R, Segal H, et al. Fabry disease in unselected patients with TIA or stroke: population-based study. Eur J Neurol. 2012;19:1427–1432. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2012.03739.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Viana-Baptista M. Stroke and Fabry disease. J Neurol. 2012;259:1019–1028. doi: 10.1007/s00415-011-6278-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Linn J, Fesl G, Ottomeyer C, et al. Intra-arterial application of nimodipine in reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndrome: a diagnostic tool in select cases? Cephalalgia. 2011;31:1074–1081. doi: 10.1177/0333102410394673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ducros A, Fiedler U, Porcher R, Boukobza M, Stapf C, Bousser MG. Hemorrhagic manifestations of reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndrome: frequency, features, and risk factors. Stroke. 2010;41:2505–2511. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.109.572313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]