Ancient Egyptian literature

古埃及文学

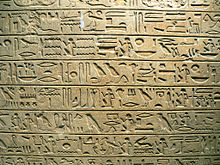

新王国卢克索神庙出土的带有 "拉美西斯二世 "刻痕的埃及象形文字

| History of literature 文学史 by era 时代 |

|---|

| Ancient (corpora) 古代(语料库) |

| Early medieval 中世纪早期 |

|

| Medieval by century 按世纪划分的中世纪 |

|

Early modern by century 按世纪划分的早期现代 |

| Modern by century 按世纪划分的现代 |

| Contemporary by century 按世纪划分的当代 |

|

|

| Ancient Egyptian 古埃及 culture 文化 |

|---|

Ancient Egyptian literature was written with the Egyptian language from ancient Egypt's pharaonic period until the end of Roman domination. It represents the oldest corpus of Egyptian literature. Along with Sumerian literature, it is considered the world's earliest literature.[1]

古埃及文学是自古埃及法老时期至罗马统治结束期间用埃及语言写成的。它代表了最古老的埃及文学。它与苏美尔文学一起被认为是世界上最早的文学。 [1]

Writing in ancient Egypt—both hieroglyphic and hieratic—first appeared in the late 4th millennium BC during the late phase of predynastic Egypt. By the Old Kingdom (26th century BC to 22nd century BC), literary works included funerary texts, epistles and letters, hymns and poems, and commemorative autobiographical texts recounting the careers of prominent administrative officials. It was not until the early Middle Kingdom (21st century BC to 17th century BC) that a narrative Egyptian literature was created. This was a "media revolution" which, according to Richard B. Parkinson, was the result of the rise of an intellectual class of scribes, new cultural sensibilities about individuality, unprecedented levels of literacy, and mainstream access to written materials.[2] The creation of literature was thus an elite exercise, monopolized by a scribal class attached to government offices and the royal court of the ruling pharaoh. However, there is no full consensus among modern scholars concerning the dependence of ancient Egyptian literature on the sociopolitical order of the royal courts.

古埃及的文字--象形文字和象形文字--最早出现在公元前 4 世纪晚期的前王朝埃及晚期。到了古王国时期(公元前 26 世纪至公元前 22 世纪),文学作品包括殡葬文本、书信、赞美诗和诗歌,以及记述著名行政官员职业生涯的纪念性自传文本。直到中王国早期(公元前 21 世纪至公元前 17 世纪),埃及叙事文学才得以产生。理查德-B-帕金森(Richard B. Parkinson)认为,这是一场 "媒体革命",是知识分子文士阶层崛起、新的个性文化意识、前所未有的识字率以及主流社会获取书面材料的结果。 [2] 因此,文学创作是一项精英活动,由隶属于政府办公室和法老王宫廷的文士阶层垄断。然而,对于古埃及文学对王室社会政治秩序的依赖性,现代学者并没有达成完全一致的看法。

Middle Egyptian, the spoken language of the Middle Kingdom, became a classical language during the New Kingdom (16th century BC to 11th century BC), when the vernacular language known as Late Egyptian first appeared in writing. Scribes of the New Kingdom canonized and copied many literary texts written in Middle Egyptian, which remained the language used for oral readings of sacred hieroglyphic texts. Some genres of Middle Kingdom literature, such as "teachings" and fictional tales, remained popular in the New Kingdom, although the genre of prophetic texts was not revived until the Ptolemaic period (4th century BC to 1st century BC). Popular tales included the Story of Sinuhe and The Eloquent Peasant, while important teaching texts include the Instructions of Amenemhat and The Loyalist Teaching. By the New Kingdom period, the writing of commemorative graffiti on sacred temple and tomb walls flourished as a unique genre of literature, yet it employed formulaic phrases similar to other genres. The acknowledgment of rightful authorship remained important only in a few genres, while texts of the "teaching" genre were pseudonymous and falsely attributed to prominent historical figures.

中古埃及语是中王国的口语,在新王国时期(公元前 16 世纪至公元前 11 世纪)成为一种经典语言,当时被称为晚期埃及语的白话首次出现在文字中。新王国的文士们将许多用中古埃及语书写的文学作品封为圣书并加以复制,中古埃及语仍然是口头朗读神圣象形文字时使用的语言。中王国文学的一些体裁,如 "教诲 "和虚构故事,在新王国仍然很流行,尽管预言文体直到托勒密时期(公元前 4 世纪至公元前 1 世纪)才得以恢复。脍炙人口的故事包括《西努赫的故事》和《能言善辩的农民》,而重要的教诲文本则包括《阿门内哈特的指示》和《忠诚者的教诲》。到了新王国时期,在神庙和陵墓墙壁上书写纪念性涂鸦作为一种独特的文学体裁得到了蓬勃发展,但它所使用的公式化短语与其他体裁相似。只有在少数体裁中,对合法作者的承认仍然很重要,而 "教诲 "体裁的文章则是假名,并假借历史名人之名。

Ancient Egyptian literature has been preserved on a wide variety of media. This includes papyrus scrolls and packets, limestone or ceramic ostraca, wooden writing boards, monumental stone edifices and coffins. Texts preserved and unearthed by modern archaeologists represent a small fraction of ancient Egyptian literary material. The area of the floodplain of the Nile is under-represented because the moist environment is unsuitable for the preservation of papyri and ink inscriptions. On the other hand, hidden caches of literature, buried for thousands of years, have been discovered in settlements on the dry desert margins of Egyptian civilization.

古埃及文献保存在多种媒介上。其中包括纸莎草纸卷轴和纸包、石灰石或陶瓷骨架、木质书写板、不朽的石头建筑和棺木。现代考古学家保存和出土的文字只占古埃及文学材料的一小部分。尼罗河冲积平原地区出土的文字较少,因为潮湿的环境不适合保存纸莎草纸和墨水铭文。另一方面,在埃及文明的沙漠边缘干旱地区的居民点,也发现了埋藏了数千年的文学藏品。

Scripts, media, and languages

脚本、媒体和语言[edit]

Hieroglyphs, hieratic, and Demotic

象形文字、象形文字和德莫西文字[edit]

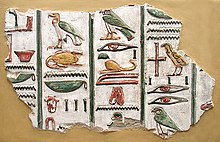

旧王国时期埃及公主奈菲尔提贝特(Neferetiabet)的石板石碑(年代约为公元前 2590-2565 年),出自她在吉萨的陵墓,石灰石上雕刻和绘有象形文字 [3] .

By the Early Dynastic Period in the late 4th millennium BC, Egyptian hieroglyphs and their cursive form hieratic were well-established written scripts.[4] Egyptian hieroglyphs are small artistic pictures of natural objects.[5] For example, the hieroglyph for door-bolt, pronounced se, produced the s sound; combined with another or multiple hieroglyphs, one could thus spell out the sound of words for more abstract concepts like sorrow, happiness, beauty, and evil.[6] The Narmer Palette, dated c. 3100 BC during the last phase of Predynastic Egypt, combines the hieroglyphs for catfish and chisel to produce the name of King Narmer.[7]

到公元前四千年晚期的早期王朝时期,埃及象形文字及其草书形式象形文字已成为成熟的书面文字。 [4] 埃及象形文字是自然物体的小型艺术图画。 [5] 例如,"门闩 "的象形文字读作 se,会发出 s 的声音;与另一个或多个象形文字结合,就可以拼出表示悲伤、幸福、美丽和邪恶等更抽象概念的单词的声音。 [6] 纳尔默调色板(Narmer Palette)的年代约为公元前 3100 年,是埃及前王朝的最后一个阶段,它将鲶鱼和凿子的象形文字组合在一起,产生了纳尔默国王的名字。 [7]

The Egyptians called their hieroglyphs "words of god" and reserved their use for exalted purposes, such as communicating with divinities and spirits of the dead through funerary texts.[8] Each hieroglyphic word represented both a specific object and embodied the essence of that object, recognizing it as divinely made and belonging within the greater cosmos.[9] Through acts of priestly ritual, like burning incense, the priest allowed spirits and deities to read the hieroglyphs decorating the surfaces of temples.[10] In funerary texts beginning in and following the Twelfth Dynasty, the Egyptians believed that disfiguring, and even omitting certain hieroglyphs, brought consequences, either good or bad, for a deceased tomb occupant whose spirit relied on the texts as a source of nourishment in the afterlife.[11] Mutilating the hieroglyph of a venomous snake, or other dangerous animal, removed a potential threat.[11] However, removing every instance of the hieroglyphs representing a deceased person's name would deprive his or her soul of the ability to read the funerary texts and condemn that soul to an inanimate existence.[11]

埃及人称他们的象形文字为 "神的文字",并将其用于崇高的目的,例如通过殡葬文字与神灵和亡灵沟通。 [8] 每个象形文字既代表一个特定的物体,又体现了该物体的本质,承认它是神造的,属于大宇宙的一部分。 [9] 通过祭司仪式(如焚香),祭司可以让神灵读懂装饰在神庙表面的象形文字。 [10] 从第十二王朝开始,埃及人认为,在墓葬文字中毁容,甚至省略某些象形文字,都会给已故的墓主人带来或好或坏的后果,而墓主人的灵魂则依赖这些文字作为来世的养料。 [11] 篡改毒蛇或其他危险动物的象形文字可以消除潜在的威胁。 [11] 但是,如果把代表死者姓名的象形文字全部去掉,就会使死者的灵魂失去阅读墓葬文字的能力,并使其灵魂注定要无生命地存在。 [11]

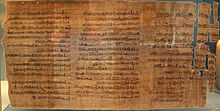

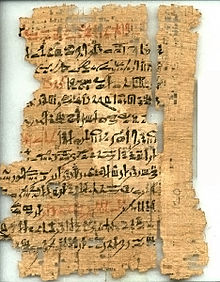

阿伯特纸莎草纸(Abbott Papyrus)是用象形文字书写的记录;它描述了对底比斯墓葬群中王室陵墓的检查,年代为拉美西斯九世的第 16 个王位年,约公元前 1110 年。

Hieratic is a simplified, cursive form of Egyptian hieroglyphs.[12] Like hieroglyphs, hieratic was used in sacred and religious texts. By the 1st millennium BC, calligraphic hieratic became the script predominantly used in funerary papyri and temple rolls.[13] Whereas the writing of hieroglyphs required the utmost precision and care, cursive hieratic could be written much more quickly and was therefore more practical for scribal record-keeping.[14] Its primary purpose was to serve as a shorthand script for non-royal, non-monumental, and less formal writings such as private letters, legal documents, poems, tax records, medical texts, mathematical treatises, and instructional guides.[15] Hieratic could be written in two different styles; one was more calligraphic and usually reserved for government records and literary manuscripts, the other was used for informal accounts and letters.[16]

象形文字是埃及象形文字的一种简化草书形式。 [12] 与象形文字一样,象形文字也用于神圣和宗教文本。到公元前一千年,书法象形文字成为主要用于墓葬纸莎草纸和神庙卷轴的文字。 [13] 象形文字的书写需要极高的精确度和细心,而草书象形文字的书写速度更快,因此更适合文士记录。 [14] 它的主要用途是作为一种速记文字,用于非王室、非纪念性和不太正式的写作,如私人信件、法律文件、诗歌、税务记录、医学文本、数学论文和教学指南。 [15] 象形文字有两种不同的书写风格:一种是书法风格,通常用于政府记录和文学手稿;另一种用于非正式账目和信件。 [16]

By the mid-1st millennium BC, hieroglyphs and hieratic were still used for royal, monumental, religious, and funerary writings, while a new, even more cursive script was used for informal, day-to-day writing: Demotic.[13] The final script adopted by the ancient Egyptians was the Coptic alphabet, a revised version of the Greek alphabet.[17] Coptic became the standard in the 4th century AD when Christianity became the state religion throughout the Roman Empire; hieroglyphs were discarded as idolatrous images of a pagan tradition, unfit for writing the Biblical canon.[17]

到公元前一千年中期,象形文字和象形文字仍被用于皇家、纪念碑、宗教和殡葬方面的书写,而一种新的、更加草书的文字则被用于非正式的日常书写:德莫提克文。 [13] 古埃及人最终采用的文字是科普特字母,它是希腊字母的修订版。 [17] 公元 4 世纪,当基督教成为整个罗马帝国的国教时,科普特字母成为标准文字;象形文字被视为异教传统的偶像崇拜图像,不适合书写《圣经》。 [17]

Writing implements and materials

书写工具和材料[edit]

埃及第二十一王朝(约公元前 1070-945 年)期间提及参与检查和清理陵墓的官员的象形文字浮雕

Egyptian literature was produced on a variety of media. Along with the chisel, necessary for making inscriptions on stone, the chief writing tool of ancient Egypt was the reed pen, a reed fashioned into a stem with a bruised, brush-like end.[18] With pigments of carbon black and red ochre, the reed pen was used to write on scrolls of papyrus—a thin material made from beating together strips of pith from the Cyperus papyrus plant—as well as on small ceramic or limestone potsherds known as ostraca.[19] It is thought that papyrus rolls were moderately expensive commercial items, since many are palimpsests, manuscripts that have had their original contents erased or scraped off to make room for new written works.[20] This, along with the practice of tearing pieces off of larger papyrus documents to make smaller letters, suggests that there were seasonal shortages caused by the limited growing season of Cyperus papyrus.[20] It also explains the frequent use of ostraca and limestone flakes as writing media for shorter written works.[21] In addition to stone, ceramic ostraca, and papyrus, writing media also included wood, ivory, and plaster.[22]

古埃及的文学创作有多种媒介。除了在石头上刻字所需的凿子外,古埃及最主要的书写工具是芦苇笔,芦苇笔是用芦苇制成的笔杆,末端有挫伤,像毛笔一样。 [18] 芦苇笔上涂有碳黑和红赭石颜料,用来在纸莎草卷轴上书写,纸莎草卷轴是将纸莎草植物的髓条打在一起制成的薄薄的材料,芦苇笔还用来在被称为ostraca的小陶器或石灰石陶器上书写。 [19] 人们认为纸莎草纸卷是一种价格适中的商业物品,因为许多纸莎草纸卷都是重写本,即为了给新的文字作品腾出空间而擦去或刮掉了原有内容的手稿。 [20] 这一点,以及从较大的纸莎草纸文件上撕下碎片来制作较小的信件的做法,表明由于塞珀斯纸莎草纸的生长季节有限,造成了季节性短缺。 [20] 这也解释了为什么在书写较短的文字作品时经常使用ostraca和石灰石片作为书写媒介。 [21] 除了石头、陶制ostraca和纸莎草纸,书写媒介还包括木材、象牙和石膏。 [22]

By the Roman period of Egypt, the traditional Egyptian reed pen had been replaced by the chief writing tool of the Greco-Roman world: a shorter, thicker reed pen with a cut nib.[23] Likewise, the original Egyptian pigments were discarded in favor of Greek lead-based inks.[23] The adoption of Greco-Roman writing tools influenced Egyptian handwriting, as hieratic signs became more spaced, had rounder flourishes, and greater angular precision.[23]

到了埃及罗马时期,传统的埃及芦苇笔已被希腊罗马世界的主要书写工具所取代:一种笔尖较短、较粗的芦苇笔。 [23] 同样,埃及原有的颜料也被丢弃,取而代之的是希腊的铅基墨水。 [23] 希腊罗马书写工具的采用对埃及手写体产生了影响,因为象形符号的间距变得更大,花饰更圆,角度更精确。 [23]

Preservation of written material

保存书面材料[edit]

Underground Egyptian tombs built in the desert provide possibly the most protective environment for the preservation of papyrus documents. For example, there are many well-preserved Book of the Dead funerary papyri placed in tombs to act as afterlife guides for the souls of the deceased tomb occupants.[24] However, it was only customary during the late Middle Kingdom and first half of the New Kingdom to place non-religious papyri in burial chambers. Thus, the majority of well-preserved literary papyri are dated to this period.[24]

建在沙漠中的埃及地下墓穴可能为保存纸莎草纸文件提供了最具保护性的环境。例如,有许多保存完好的《亡灵书》纸莎草纸被放置在墓穴中,作为墓中死者灵魂的来世向导。 [24] 然而,只有在中王国晚期和新王国前半期才有在墓室中放置非宗教纸莎草纸的习惯。因此,大部分保存完好的文学纸莎草纸都是这一时期的作品。 [24]

Most settlements in ancient Egypt were situated on the alluvium of the Nile floodplain. This moist environment was unfavorable for long-term preservation of papyrus documents. Archaeologists have discovered a larger quantity of papyrus documents in desert settlements on land elevated above the floodplain,[25] and in settlements that lacked irrigation works, such as Elephantine, El-Lahun, and El-Hiba.[26]

古埃及的大多数定居点都位于尼罗河冲积平原上。这种潮湿的环境不利于纸莎草文献的长期保存。考古学家在高出冲积平原的沙漠定居点, [25] 以及缺乏灌溉工程的定居点(如 Elephantine、El-Lahun 和 El-Hiba)发现了大量纸莎草文献。 [26]

埃及农民收割纸莎草,出自代尔梅迪纳古墓中的一幅壁画,年代为拉美塞德早期(即第十九王朝)

Writings on more permanent media have also been lost in several ways. Stones with inscriptions were frequently re-used as building materials, and ceramic ostraca require a dry environment to ensure the preservation of the ink on their surfaces.[27] Whereas papyrus rolls and packets were usually stored in boxes for safekeeping, ostraca were routinely discarded in waste pits; one such pit was discovered by chance at the Ramesside-era village of Deir el-Medina, and has yielded the majority of known private letters on ostraca.[21] Documents found at this site include letters, hymns, fictional narratives, recipes, business receipts, and wills and testaments.[28] Penelope Wilson describes this archaeological find as the equivalent of sifting through a modern landfill or waste container.[28] She notes that the inhabitants of Deir el-Medina were incredibly literate by ancient Egyptian standards, and cautions that such finds only come "in rarefied circumstances and in particular conditions."[29]

在较为永久的媒介上书写的文字也以多种方式流失。刻有铭文的石头经常作为建筑材料被重复使用,而陶瓷骨架则需要干燥的环境来确保表面的墨迹得以保存。 [27] 纸莎草纸卷和纸包通常被存放在盒子里妥善保管,而纸莎草纸则经常被丢弃在废坑中;在拉美塞德时代的 Deir el-Medina 村偶然发现了一个这样的废坑,出土了大部分已知的纸莎草纸私人信件。 [21] 在该遗址发现的文件包括书信、赞美诗、虚构的叙述、食谱、商业收据以及遗嘱和遗书。 [28] 佩内洛普-威尔逊(Penelope Wilson)将这一考古发现描述为相当于筛选现代垃圾填埋场或垃圾容器。 [28] 她指出,按照古埃及的标准,代尔米迪纳的居民识字率非常高,并提醒说,这样的发现只有在 "罕见的环境和特殊的条件下 "才会出现。 [29]

John W. Tait stresses, "Egyptian material survives in a very uneven fashion ... the unevenness of survival comprises both time and space."[27] For instance, there is a dearth of written material from all periods from the Nile Delta but an abundance at western Thebes, dating from its heyday.[27] He notes that while some texts were copied numerous times, others survive from a single copy; for example, there is only one complete surviving copy of the Tale of the Shipwrecked Sailor from the Middle Kingdom.[30] However, Tale of the Shipwrecked Sailor also appears in fragments of texts on ostraca from the New Kingdom.[31] Many other literary works survive only in fragments or through incomplete copies of lost originals.[32]

约翰-W.泰特强调:"埃及材料的存世量非常不均衡......存世量的不均衡包括时间和空间两个方面。 [27] 例如,尼罗河三角洲各个时期的书面材料都很匮乏,但在西底比斯却有大量全盛时期的书面材料。 [27] 他指出,有些文本被抄写了无数遍,而有些文本仅存一份副本;例如,中王国时期的《遇难水手的故事》仅存一份完整的副本。 [30] 不过,《遇难水手的故事》也出现在新王国的浮雕文本片段中。 [31] 许多其他文学作品仅以片段或遗失原件的不完整副本形式存世。 [32]

Classical, Middle, Late, and Demotic Egyptian language

古埃及语、中古埃及语、晚期埃及语和德莫西埃及语[edit]

拉美西斯二世(公元前 1279-1213 年)统治时期建造的拉美西姆大殿(卢克索)中的柱子,上面刻有和绘有埃及象形文字

Although writing first appeared during the very late 4th millennium BC, it was only used to convey short names and labels; connected strings of text did not appear until about 2600 BC, at the beginning of the Old Kingdom.[33] This development marked the beginning of the first known phase of the Egyptian language: Old Egyptian.[33] Old Egyptian remained a spoken language until about 2100 BC, when, during the beginning of the Middle Kingdom, it evolved into Middle Egyptian.[33] While Middle Egyptian was closely related to Old Egyptian, Late Egyptian was significantly different in grammatical structure. Late Egyptian possibly appeared as a vernacular language as early as 1600 BC, but was not used as a written language until c. 1300 BC during the Amarna Period of the New Kingdom.[34] Late Egyptian evolved into Demotic by the 7th century BC, and although Demotic remained a spoken language until the 5th century AD, it was gradually evolved into Coptic beginning in the 1st century AD.[35]

虽然文字最早出现在公元前 4000 年的晚期,但它只是用来传递简短的名称和标签;直到公元前 2600 年左右,即古王国初期,才出现了连接的文字串。 [33] 这一发展标志着埃及语言第一个已知阶段的开始:古埃及语。 [33] 古埃及语一直是一种口语,直到公元前 2100 年左右,在中王国初期,古埃及语演变为中古埃及语。 [33] 虽然中古埃及语与古埃及语关系密切,但晚期埃及语在语法结构上有很大不同。晚期埃及语可能早在公元前 1600 年就作为一种方言出现了,但直到公元前 1300 年左右新王国阿玛尔纳时期才作为一种书面语言使用。 [34] 到公元前 7 世纪,晚期埃及语演变成了去墨提语,虽然去墨提语在公元 5 世纪之前一直是一种口语,但从公元 1 世纪开始,它逐渐演变成了科普特语。 [35]

Hieratic was used alongside hieroglyphs for writing in Old and Middle Egyptian, becoming the dominant form of writing in Late Egyptian.[36] By the New Kingdom and throughout the rest of ancient Egyptian history, Middle Egyptian became a classical language that was usually reserved for reading and writing in hieroglyphs[37] and the spoken language for more exalted forms of literature, such as historical records, commemorative autobiographies, hymns, and funerary spells.[38] However, Middle Kingdom literature written in Middle Egyptian was also rewritten in hieratic during later periods.[39]

在古埃及语和中古埃及语中,象形文字与象形文字一起用于书写,在晚期埃及语中成为主要的书写形式。 [36] 到了新王国时期以及古埃及历史的其他时期,中古埃及语成为一种古典语言,通常用于象形文字的阅读和书写 [37] ,而口语则用于更高级的文学形式,如历史记录、纪念性自传、赞美诗和丧葬咒语。 [38] 不过,中王国时期用中古埃及语书写的文学作品在后期也被改写成象形文字。 [39]

Literary functions: social, religious and educational

文学功能:社会、宗教和教育[edit]

埃及第五王朝(公元前 25 至 24 世纪)吉萨西部墓地发现的埃及抄写员坐像,膝上放着一份纸莎草纸文件

Throughout ancient Egyptian history, the ability to read and write were the main requirements for serving in public office, although government officials were assisted in their day-to-day work by an elite, literate social group known as scribes.[40] As evidenced by Papyrus Anastasi I of the Ramesside Period, scribes could even be expected, according to Wilson, "...to organize the excavation of a lake and the building of a brick ramp, to establish the number of men needed to transport an obelisk and to arrange the provisioning of a military mission".[41] Besides government employment, scribal services in drafting letters, sales documents, and legal documents would have been frequently sought by illiterate people.[42] Literate people are thought to have comprised only 1% of the population,[43] the remainder being illiterate farmers, herdsmen, artisans, and other laborers,[44] as well as merchants who required the assistance of scribal secretaries.[45] The privileged status of the scribe over illiterate manual laborers was the subject of a popular Ramesside Period instructional text, The Satire of the Trades, where lowly, undesirable occupations, for example, potter, fisherman, laundry man, and soldier, were mocked and the scribal profession praised.[46] A similar demeaning attitude towards the illiterate is expressed in the Middle Kingdom Teaching of Khety, which is used to reinforce the scribes' elevated position within the social hierarchy.[47]

纵观古埃及历史,读写能力是担任公职的主要要求,尽管政府官员的日常工作得到了一个被称为文士的识字社会精英群体的协助。 [40] 根据威尔逊的说法,正如拉美塞德时期的纸莎草《阿纳斯塔西一世》所证明的那样,文士甚至可以"......组织挖掘湖泊和建造砖砌斜坡,确定运输方尖碑所需的人数,安排军事代表团的供给"。 [41] 除了在政府部门工作,文盲也经常需要文士提供起草信件、销售文件和法律文件的服务。 [42] 人们认为文盲只占总人口的 1%, [43] 其余是不识字的农民、牧民、工匠和其他劳动者, [44] 还有需要文士秘书帮助的商人。 [45] 在拉美塞德时期流行的教科书《行业讽刺诗》中,文士相对于文盲体力劳动者的特权地位受到了嘲讽,而文士职业则受到了赞扬。 [46] 《中土教义》中也表达了对文盲的类似贬低态度,用来强化文士在社会等级中的崇高地位。 [47]

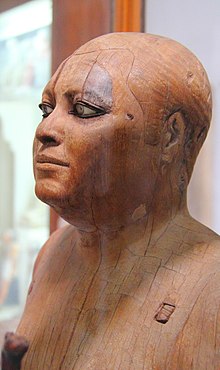

旧王国第五或第四王朝文士卡帕尔的木雕像,出土于萨卡拉,约公元前 2500 年

The scribal class was the social group responsible for maintaining, transmitting, and canonizing literary classics, and writing new compositions.[48] Classic works, such as the Story of Sinuhe and Instructions of Amenemhat, were copied by schoolboys as pedagogical exercises in writing and to instill the required ethical and moral values that distinguished the scribal social class.[49] Wisdom texts of the "teaching" genre represent the majority of pedagogical texts written on ostraca during the Middle Kingdom; narrative tales, such as Sinuhe and King Neferkare and General Sasenet, were rarely copied for school exercises until the New Kingdom.[50] William Kelly Simpson describes narrative tales such as Sinuhe and The Shipwrecked Sailor as "...instructions or teachings in the guise of narratives", since the main protagonists of such stories embodied the accepted virtues of the day, such as love of home or self-reliance.[51]

文士阶层是负责维护、传播文学经典并使之成为经典以及撰写新作品的社会群体。 [48] 经典作品,如《西努赫的故事》和《阿门内哈特的指示》,被学生们抄写,作为写作教学练习,并灌输所需的伦理道德价值观,这也是文士社会阶层的特征。 [49] 在中王国时期,"教学 "体裁的智慧课文占写在浮雕上的教学课文的绝大多数;叙事故事,如《西努赫与奈费卡雷国王》和《萨塞内将军》,在新王国之前很少被抄写作为学校练习。 [50] 威廉-凯利-辛普森(William Kelly Simpson)将《西努赫》和《遇船难的水手》等叙事故事描述为"......披着叙事外衣的指令或教诲",因为这些故事的主人公体现了当时公认的美德,如热爱家园或自力更生。 [51]

There are some known instances where those outside the scribal profession were literate and had access to classical literature. Menena, a draughtsman working at Deir el-Medina during the Twentieth dynasty of Egypt, quoted passages from the Middle Kingdom narratives Eloquent Peasant and Tale of the Shipwrecked Sailor in an instructional letter reprimanding his disobedient son.[31] Menena's Ramesside contemporary Hori, the scribal author of the satirical letter in Papyrus Anastasi I, admonished his addressee for quoting the Instruction of Hardjedef in the unbecoming manner of a non-scribal, semi-educated person.[31] Hans-Werner Fischer-Elfert further explains this perceived amateur affront to orthodox literature:

在一些已知的例子中,抄写员职业之外的人也识字并能接触到古典文学。埃及第二十王朝时期在代尔麦地那工作的绘图员梅内纳在一封训斥不听话儿子的教导信中引用了中王国叙事诗《雄辩的农民》和《遇难水手的故事》中的段落。 [31] 与梅内纳同时代的拉美塞德人堀(Hori)是纸莎草《阿纳斯塔西一世》(Anastasi I)中讽刺信的抄写员,他在信中告诫收信人不要以非抄写员、半受过教育的人的不恰当方式引用《哈杰德夫的教诲》。 [31] 汉斯-维尔纳-费舍尔-埃尔费特进一步解释了这一被认为是对正统文学的业余侮辱:

What may be revealed by Hori's attack on the way in which some Ramesside scribes felt obliged to demonstrate their greater or lesser acquaintance with ancient literature is the conception that these venerable works were meant to be known in full and not to be misused as quarries for popular sayings mined deliberately from the past. The classics of the time were to be memorized completely and comprehended thoroughly before being cited.[52]

堀对一些拉美塞德文士的抨击揭示了这样一种观念,即这些可敬的作品是要让人全面了解的,而不是被滥用为刻意从过去挖掘出来的流行语。当时的经典作品在被引用之前,必须完全背诵并彻底理解。 [52]

塞提一世神庙的象形文字,现藏于大英博物馆

There is limited but solid evidence in Egyptian literature and art for the practice of oral reading of texts to audiences.[53] The oral performance word "to recite" (šdj) was usually associated with biographies, letters, and spells.[54] Singing (ḥsj) was meant for praise songs, love songs, funerary laments, and certain spells.[54] Discourses such as the Prophecy of Neferti suggest that compositions were meant for oral reading among elite gatherings.[54] In the 1st millennium BC Demotic short story cycle centered on the deeds of Petiese, the stories begin with the phrase "The voice which is before Pharaoh", which indicates that an oral speaker and audience was involved in the reading of the text.[55] A fictional audience of high government officials and members of the royal court are mentioned in some texts, but a wider, non-literate audience may have been involved.[56] For example, a funerary stela of Senusret I (r. 1971–1926 BC) explicitly mentions people who will gather and listen to a scribe who "recites" the stela inscriptions out loud.[56]

在埃及文学和艺术中,向听众口头朗读文本的做法虽然证据有限,但却是确凿的。 [53] 口头表演词 "朗诵"(šdj)通常与传记、书信和咒语有关。 [54] 唱歌(ḥsj)指的是赞美歌、情歌、丧葬哀歌和某些咒语。 [54] 《奈菲尔蒂的预言》等论述表明,作品是供精英聚会时口头朗读的。 [54] 在公元前一千年的德莫尼短篇故事集中,故事以 Petiese 的事迹为中心,故事以 "法老面前的声音 "开头,这表明在阅读文本时有口头演讲者和听众参与。 [55] 有些文本中提到了由政府高官和王室成员组成的虚构听众,但也可能有更广泛的非文盲听众参与其中。 [56] 例如,塞努斯雷特一世(Senusret I,公元前 1971-1926 年)的一块墓碑明确提到人们会聚集在一起,聆听文士大声 "朗诵 "碑文。 [56]

Literature also served religious purposes. Beginning with the Pyramid Texts of the Old Kingdom, works of funerary literature written on tomb walls, and later on coffins, and papyri placed within tombs, were designed to protect and nurture souls in their afterlife.[57] This included the use of magical spells, incantations, and lyrical hymns.[57] Copies of non-funerary literary texts found in non-royal tombs suggest that the dead could entertain themselves in the afterlife by reading these teaching texts and narrative tales.[58]

文学也有宗教用途。从旧王国的金字塔文本开始,写在墓壁上的殡葬文学作品,以及后来写在棺木上、放在墓室里的纸莎草纸,都是为了保护和培养灵魂的来世。 [57] 其中包括使用魔法咒语、咒语和抒情诗。 [57] 在非王室墓葬中发现的非寓言文学文本副本表明,死者在来世可以通过阅读这些教学文本和叙事故事来自娱自乐。 [58]

Although the creation of literature was predominantly a male scribal pursuit, some works are thought to have been written by women. For example, several references to women writing letters and surviving private letters sent and received by women have been found.[59] However, Edward F. Wente asserts that, even with explicit references to women reading letters, it is possible that women employed others to write documents.[60]

虽然文学创作主要是男性文士的追求,但也有一些作品被认为是由女性撰写的。例如,我们发现了一些关于女性写信的记载,以及现存的女性收发的私人信件。 [59] 不过,爱德华-F-温特(Edward F. Wente)断言,即使明确提到女性阅读信件,女性也有可能雇用他人撰写文件。 [60]

Dating, setting, and authorship

日期、背景和作者[edit]

文士首领米纳赫特的石碑,象形文字铭文,年代为阿伊统治时期(公元前 1323-1319 年)

Richard B. Parkinson and Ludwig D. Morenz write that ancient Egyptian literature—narrowly defined as belles-lettres ("beautiful writing")—was not recorded in written form until the early Twelfth dynasty of the Middle Kingdom.[61] Old Kingdom texts served mainly to maintain the divine cults, preserve souls in the afterlife, and document accounts for practical uses in daily life. It was not until the Middle Kingdom that texts were written for the purpose of entertainment and intellectual curiosity.[62] Parkinson and Morenz also speculate that written works of the Middle Kingdom were transcriptions of the oral literature of the Old Kingdom.[63] It is known that some oral poetry was preserved in later writing; for example, litter-bearers' songs were preserved as written verses in tomb inscriptions of the Old Kingdom.[62]

理查德-B-帕金森和路德维希-D.莫伦茨写道,古埃及文学--狭义地定义为 belles-lettres("美文")--直到中王国第十二王朝早期才以书面形式记录下来。 [61] 古王国的文字主要用于维护神灵崇拜、保存来世的灵魂以及记录日常生活中的实际用途。直到中王国时期,才出现了以娱乐和求知为目的的文字。 [62] 帕金森和莫伦茨还推测,中王国的书面作品是对古王国口头文学的转录。 [63] 众所周知,一些口头诗歌在后来的文字中得到了保留;例如,轿夫的歌谣在古王国的墓葬碑文中以书面诗歌的形式得到了保留。 [62]

Dating texts by methods of palaeography, the study of handwriting, is problematic because of differing styles of hieratic script.[64] The use of orthography, the study of writing systems and symbol usage, is also problematic, since some texts' authors may have copied the characteristic style of an older archetype.[64] Fictional accounts were often set in remote historical settings, the use of contemporary settings in fiction being a relatively recent phenomenon.[65] The style of a text provides little help in determining an exact date for its composition, as genre and authorial choice might be more concerned with the mood of a text than the era in which it was written.[66] For example, authors of the Middle Kingdom could set fictional wisdom texts in the golden age of the Old Kingdom (e.g. Kagemni, Ptahhotep, and the prologue of Neferti), or they could write fictional accounts placed in a chaotic age resembling more the problematic life of the First Intermediate Period (e.g. Merykare and The Eloquent Peasant).[67] Other fictional texts are set in illo tempore (in an indeterminable era) and usually contain timeless themes.[68]

由于象形文字的风格各异,用古文字学(即笔迹研究)的方法来确定文本的年代是有问题的。 [64] 使用正字法(即研究书写系统和符号用法的方法)也有问题,因为有些文本的作者可能抄袭了较早原型的特征风格。 [64] 小说通常以遥远的历史背景为背景,而在小说中使用当代背景则是一个相对较新的现象。 [65] 文本的风格对于确定其确切的创作年代帮助不大,因为体裁和作者的选择可能更关注文本的情绪,而不是其写作年代。 [66] 例如,中王国的作者可以将虚构的智慧文本设定为旧王国的黄金时代(如《卡格尼》(Kagemni)、《普塔霍特普》(Ptahhotep)和《奈菲尔提》(Neferti)的序言),也可以将虚构的故事设定为一个混乱的时代,更类似于第一中间期问题重重的生活(如《梅里卡尔》(Merykare)和《雄辩的农民》(The Eloquent Peasant))。 [67] 其他虚构文本以 illo tempore(不确定的时代)为背景,通常包含永恒的主题。 [68]

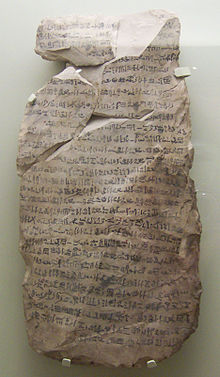

Heqanakht 纸莎草纸之一,这是一套中王国第十一王朝时期的私人信件 [69] .

Parkinson writes that nearly all literary texts were pseudonymous, and frequently falsely attributed to well-known male protagonists of earlier history, such as kings and viziers.[70] Only the literary genres of "teaching" and "laments/discourses" contain works attributed to historical authors; texts in genres such as "narrative tales" were never attributed to a well-known historical person.[71] Tait asserts that during the Classical Period of Egypt, "Egyptian scribes constructed their own view of the history of the role of scribes and of the 'authorship' of texts", but during the Late Period, this role was instead maintained by the religious elite attached to the temples.[72]

帕金森写道,几乎所有的文学文本都是假名,而且经常被错误地归于早期历史上著名的男性主角,如国王和大臣。 [70] 只有 "教诲 "和 "哀歌/论述 "这两种文学体裁中的作品被认为是历史作者的作品;"叙事故事 "等体裁中的文本从未被认为是某个著名历史人物的作品。 [71] 泰特断言,在埃及古典时期,"埃及文士构建了自己对文士角色和文本'作者'身份的历史观",但在晚期,这一角色反而由附属于神庙的宗教精英来维护。 [72]

There are a few exceptions to the rule of pseudonymity. The real authors of some Ramesside Period teaching texts were acknowledged, but these cases are rare, localized, and do not typify mainstream works.[73] Those who wrote private and sometimes model letters were acknowledged as the original authors. Private letters could be used in courts of law as testimony, since a person's unique handwriting could be identified as authentic.[74] Private letters received or written by the pharaoh were sometimes inscribed in hieroglyphics on stone monuments to celebrate kingship, while kings' decrees inscribed on stone stelas were often made public.[75]

笔名规则也有少数例外。一些拉美塞德时期教学文本的真正作者得到了承认,但这种情况很少见,而且是局部性的,并不是主流作品的典型。 [73] 写私人信件、有时是示范信件的人被承认为原作者。私人信件可以在法庭上用作证词,因为一个人独特的笔迹可以被认定为真迹。 [74] 法老收到或书写的私人信件有时会用象形文字刻在石碑上,以庆祝其王权,而刻在石碑上的国王法令通常会被公开。 [75]

Literary genres and subjects

文学流派和主题[edit]

Modern Egyptologists categorize Egyptian texts into genres, for example "laments/discourses" and narrative tales.[76] The only genre of literature named as such by the ancient Egyptians was the "teaching" or sebayt genre.[77] Parkinson states that the titles of a work, its opening statement, or key words found in the body of text should be used as indicators of its particular genre.[78] Only the genre of "narrative tales" employed prose, yet many of the works of that genre, as well as those of other genres, were written in verse.[79] Most ancient Egyptian verses were written in couplet form, but sometimes triplets and quatrains were used.[80]

现代埃及学家将埃及文本分为多种体裁,例如 "哀歌/论述 "和叙事故事。 [76] 古埃及人唯一命名的文学体裁是 "教诲 "或 "sebayt "体裁。 [77] 帕金森指出,作品的标题、开篇语或正文中的关键词应作为其特定体裁的标志。 [78] 只有 "叙事故事 "这一体裁使用散文,但该体裁以及其他体裁的许多作品都是用诗歌写成的。 [79] 古埃及诗歌大多采用对偶形式,但有时也使用三联和四联。 [80]

Instructions and teachings

指示和教诲[edit]

新王国时期的纸莎草文本,用象形文字书写的《洛亚教义》。

The "instructions" or "teaching" genre, as well as the genre of "reflective discourses", can be grouped in the larger corpus of wisdom literature found in the ancient Near East.[81] The genre is didactic in nature and is thought to have formed part of the Middle Kingdom scribal education syllabus.[82] However, teaching texts often incorporate narrative elements that can instruct as well as entertain.[82] Parkinson asserts that there is evidence that teaching texts were not created primarily for use in scribal education, but for ideological purposes.[83] For example, Adolf Erman (1854–1937) writes that the fictional instruction given by Amenemhat I (r. 1991–1962 BC) to his sons "...far exceeds the bounds of school philosophy, and there is nothing whatever to do with school in a great warning his children to be loyal to the king".[84] While narrative literature, embodied in works such as The Eloquent Peasant, emphasize the individual hero who challenges society and its accepted ideologies, the teaching texts instead stress the need to comply with society's accepted dogmas.[85]

训示 "或 "教导 "体裁以及 "反思性论述 "体裁可归入古代近东的智慧文学大系。 [81] 该体裁具有说教性质,被认为是中王国文士教育大纲的一部分。 [82] 不过,教学课文通常包含叙事元素,既能寓教于乐,也能寓教于乐。 [82] 帕金森断言,有证据表明,教学课文的创作主要不是为了用于抄写员教育,而是出于意识形态的目的。 [83] 例如,阿道夫-埃尔曼(Adolf Erman,1854-1937 年)写道,阿门内姆哈特一世(公元前 1991-1962 年)对儿子们的虚构教导"......远远超出了学校哲学的范围,一个伟大的人告诫他的孩子们要忠于国王,这与学校没有任何关系"。 [84] 《雄辩的农民》等叙事文学作品强调挑战社会及其公认意识形态的个人英雄,而教学课文则强调必须遵守社会公认的教条。 [85]

Key words found in teaching texts include "to know" (rḫ) and "to teach" (sbꜣ).[81] These texts usually adopt the formulaic title structure of "the instruction of X made for Y", where "X" can be represented by an authoritative figure (such as a vizier or king) providing moral guidance to his son(s).[86] It is sometimes difficult to determine how many fictional addressees are involved in these teachings, since some texts switch between singular and plural when referring to their audiences.[87]

教学文本中的关键词包括 "知道"(rḫ)和 "教导"(sbꜣ)。 [81] 这些文本通常采用 "X 为 Y 所做的教导 "的公式化标题结构,其中 "X "可以代表一个权威人物(如大臣或国王),为他的儿子提供道德指导。 [86] 有时很难确定这些教诲涉及多少虚构的受众,因为有些文本在提及受众时会切换单数和复数。 [87]

Examples of the "teaching" genre include the Maxims of Ptahhotep, Instructions of Kagemni, Teaching for King Merykare, Instructions of Amenemhat, Instruction of Hardjedef, Loyalist Teaching, and Instructions of Amenemope.[88] Teaching texts that have survived from the Middle Kingdom were written on papyrus manuscripts.[89] No educational ostraca from the Middle Kingdom have survived.[89] The earliest schoolboy's wooden writing board, with a copy of a teaching text (i.e. Ptahhotep), dates to the Eighteenth dynasty.[89] Ptahhotep and Kagemni are both found on the Prisse Papyrus, which was written during the Twelfth dynasty of the Middle Kingdom.[90] The entire Loyalist Teaching survives only in manuscripts from the New Kingdom, although the entire first half is preserved on a Middle Kingdom biographical stone stela commemorating the Twelfth dynasty official Sehetepibre.[91] Merykare, Amenemhat, and Hardjedef are genuine Middle Kingdom works, but only survive in later New Kingdom copies.[92] Amenemope is a New Kingdom compilation.[93]

[88] 中王国流传下来的教学文本都写在纸莎草纸手稿上。 [89] 中王国的教育用纸没有流传下来。 [89] 最早的学生木制写字板上有教学课文(即《普塔霍特普》)的副本,可以追溯到第十八王朝。 [89] 普塔霍特普和卡吉尼都出现在普里斯纸莎草纸上,该纸莎草纸成书于中王国第十二王朝。 [90] 《忠诚者教诲》全文仅存于新王国时期的手稿中,不过前半部分全文保存在中王国时期纪念第十二王朝官员塞特皮布的传记石碑上。 [91] 《Merykare》、《Amenemhat》和《Hardjedef》是真正的中王国作品,但仅存于新王国后期的副本中。 [92] 《阿梅内莫普》是新王国时期的作品。 [93]

Narrative tales and stories

叙事故事和传说[edit]

西卡纸莎草纸虽然是用第十五至第十七王朝时期的象形文字书写的,但其中的《契普斯王宫廷故事》却是用中古埃及文书写的,可追溯到第十二王朝时期。 [94]

The genre of "tales and stories" is probably the least represented genre from surviving literature of the Middle Kingdom and Middle Egyptian.[95] In Late Egyptian literature, "tales and stories" comprise the majority of surviving literary works dated from the Ramesside Period of the New Kingdom into the Late Period.[96] Major narrative works from the Middle Kingdom include the Tale of the Court of King Cheops, King Neferkare and General Sasenet, The Eloquent Peasant, Story of Sinuhe, and Tale of the Shipwrecked Sailor.[97] The New Kingdom corpus of tales includes the Quarrel of Apepi and Seqenenre, The Taking of Joppa, Tale of the Doomed Prince, Tale of Two Brothers, and the Report of Wenamun.[98] Stories from the 1st millennium BC written in Demotic include the story of the Famine Stela (set in the Old Kingdom, although written during the Ptolemaic dynasty) and short story cycles of the Ptolemaic and Roman periods that transform well-known historical figures such as Khaemweset (Nineteenth Dynasty) and Inaros (First Persian Period) into fictional, legendary heroes.[99] This is contrasted with many stories written in Late Egyptian, whose authors frequently chose divinities as protagonists and mythological places as settings.[51]

在现存的中王国和中埃及文学作品中,"故事和传说 "可能是最少见的体裁。 [95] 在晚期埃及文学中,"故事和传说 "在新王国拉美塞德时期到晚期的现存文学作品中占大多数。 [96] 中王国时期的主要叙事作品包括《契普斯王宫廷的故事》、《奈菲尔卡雷国王和萨塞内将军》、《能言善辩的农民》、《西努赫的故事》和《遇难水手的故事》。 [97] 新王国的故事集包括《阿佩皮和塞克南尔的争吵》、《攻占约帕城》、《厄运王子的故事》、《两兄弟的故事》和《韦纳蒙的报告》。 [98] 公元前一千年用狄莫提语写的故事包括《饥荒石碑》(故事发生在旧王国,但成书于托勒密王朝时期)以及托勒密和罗马时期的短篇故事集,这些故事将著名的历史人物(如卡姆维塞特(第十九王朝)和伊纳罗斯(波斯第一时期))变成了虚构的传奇英雄。 [99] 这与许多用晚期埃及文写成的故事形成鲜明对比,后者的作者经常选择神灵作为主人公,并将神话中的地方作为背景。 [51]

阿门内姆哈特一世的浮雕,由神灵陪伴;他的儿子塞努斯雷特一世在《西努赫的故事》中讲述了阿门内姆哈特一世之死。

Parkinson defines tales as "...non-commemorative, non-functional, fictional narratives" that usually employ the key word "narrate" (sdd).[95] He describes it as the most open-ended genre, since the tales often incorporate elements of other literary genres.[95] For example, Morenz describes the opening section of the foreign adventure tale Sinuhe as a "...funerary self-presentation" that parodies the typical autobiography found on commemorative funerary stelas.[100] The autobiography is for a courier whose service began under Amenemhat I.[101] Simpson states that the death of Amenemhat I in the report given by his son, coregent, and successor Senusret I (r. 1971–1926 BC) to the army in the beginning of Sinuhe is "...excellent propaganda".[102] Morenz describes The Shipwrecked Sailor as an expeditionary report and a travel-narrative myth.[100] Simpson notes the literary device of the story within a story in The Shipwrecked Sailor may provide "...the earliest examples of a narrative quarrying report".[103] With the setting of a magical desert island, and a character who is a talking snake, The Shipwrecked Sailor may also be classified as a fairy tale.[104] While stories like Sinuhe, Taking of Joppa, and the Doomed prince contain fictional portrayals of Egyptians abroad, the Report of Wenamun is most likely based on a true account of an Egyptian who traveled to Byblos in Phoenicia to obtain cedar for shipbuilding during the reign of Ramesses XI.[105]

帕金森将故事定义为"......非纪念性、非功能性的虚构叙事",通常使用关键词 "叙述"(sdd)。 [95] 他将其描述为最具开放性的体裁,因为故事通常融合了其他文学体裁的元素。 [95] 例如,莫伦茨将外国探险故事《西努赫》的开头部分描述为"......葬礼上的自我介绍",模仿了葬礼纪念碑上的典型自传。 [100] 这篇自传的作者是一名信使,他在阿门内姆哈特一世时期开始服役。 [101] 辛普森指出,在《西努赫》的开头,阿门内姆哈特一世的儿子、核心人物和继承人塞努斯雷特一世(Senusret I,公元前 1971-1926 年)向军队所作的报告中提到了阿门内姆哈特一世之死,这是"......极好的宣传"。 [102] Morenz 将《遇难水手》描述为一份远征报告和一个旅行叙事神话。 [100] 辛普森指出,《遇难船员》中的 "故事中的故事 "这一文学手法可能提供了"......最早的叙事采石报告范例"。 [103] 《遇难水手》的故事背景是一个神奇的荒岛,主人公是一条会说话的蛇,因此也可归类为童话。 [104] 《西努赫》、《攻占约帕城》和《注定要失败的王子》等故事虚构了埃及人在国外的生活,而《韦那蒙的报告》很可能是根据真实故事改编的,讲述了拉美西斯十一世统治时期,一名埃及人前往腓尼基的比布鲁斯获取造船用的雪松。 [105]

Narrative tales and stories are most often found on papyri, but partial and sometimes complete texts are found on ostraca. For example, Sinuhe is found on five papyri composed during the Twelfth and Thirteenth dynasties.[106] This text was later copied numerous times on ostraca during the Nineteenth and Twentieth dynasties, with one ostraca containing the complete text on both sides.[106]

叙事故事和传说最常出现在纸莎草纸上,但也有部分,有时甚至是完整的文本出现在纸莎草纸上。例如,《Sinuhe》见于十二和十三王朝时期的五种纸莎草纸上。 [106] 这个文本后来被多次抄写在十九和二十世纪的浮雕上,其中一张浮雕的正反两面都有完整的文本。 [106]

Laments, discourses, dialogues, and prophecies

箴言、论述、对话和预言[edit]

The Middle Kingdom genre of "prophetic texts", also known as "laments", "discourses", "dialogues", and "apocalyptic literature",[107] include such works as the Admonitions of Ipuwer, Prophecy of Neferti, and Dispute between a man and his Ba. This genre had no known precedent in the Old Kingdom and no known original compositions were produced in the New Kingdom.[108] However, works like Prophecy of Neferti were frequently copied during the Ramesside Period of the New Kingdom,[109] when this Middle Kingdom genre was canonized but discontinued.[110] Egyptian prophetic literature underwent a revival during the Greek Ptolemaic dynasty and Roman period of Egypt with works such as the Demotic Chronicle, Oracle of the Lamb, Oracle of the Potter, and two prophetic texts that focus on Nectanebo II (r. 360–343 BC) as a protagonist.[111] Along with "teaching" texts, these reflective discourses (key word mdt) are grouped with the wisdom literature category of the ancient Near East.[81]

中王国时期的 "预言文 "体裁,又称 "哀歌"、"论述"、"对话 "和 "世界末日文学", [107] 包括《伊普韦尔的训诫》、《奈菲尔蒂的预言》和《一个男人和他的巴之间的争论》等作品。这种体裁在旧王国没有已知的先例,在新王国也没有已知的原创作品。 [108] 然而,在新王国的拉美塞德时期,像《奈菲尔蒂的预言》这样的作品经常被抄袭, [109] 当时这种中王国时期的体裁已被列为经典,但已停用。 [110] 埃及预言文学在希腊托勒密王朝和罗马时期经历了一次复兴,出现了《德莫迪克纪事》、《羔羊的神谕》、《陶工的神谕》等作品,以及两部以奈克塔尼波二世(Nectanebo II,公元前 360-343 年)为主角的预言文本。 [111] 这些反思性论述(关键词 mdt)与 "教学 "文本一起被归入古代近东智慧文学类别。 [81]

鸟形态的巴,是埃及灵魂的一个组成部分,在中王国的论述中有所论及 人和他的巴之间的争执

In Middle Kingdom texts, connecting themes include a pessimistic outlook, descriptions of social and religious change, and great disorder throughout the land, taking the form of a syntactic "then-now" verse formula.[112] Although these texts are usually described as laments, Neferti digresses from this model, providing a positive solution to a problematic world.[81] Although it survives only in later copies from the Eighteenth dynasty onward, Parkinson asserts that, due to obvious political content, Neferti was originally written during or shortly after the reign of Amenemhat I.[113] Simpson calls it "...a blatant political pamphlet designed to support the new regime" of the Twelfth dynasty founded by Amenemhat, who usurped the throne from the Mentuhotep line of the Eleventh dynasty.[114] In the narrative discourse, Sneferu (r. 2613–2589 BC) of the Fourth dynasty summons to court the sage and lector priest Neferti. Neferti entertains the king with prophecies that the land will enter into a chaotic age, alluding to the First Intermediate Period, only to be restored to its former glory by a righteous king— Ameny—whom the ancient Egyptian would readily recognize as Amenemhat I.[115] A similar model of a tumultuous world transformed into a golden age by a savior king was adopted for the Lamb and Potter, although for their audiences living under Roman domination, the savior was yet to come.[116]

在中王国的文本中,连接的主题包括悲观的前景、对社会和宗教变革的描述以及整个国家的巨大混乱,其形式为句法上的 "当时-现在 "诗句。 [112] 虽然这些文本通常被描述为哀歌,但《奈菲尔提》却偏离了这一模式,为问题重重的世界提供了积极的解决方案。 [81] 虽然《奈菲尔提》仅存于第十八王朝以后的副本中,但帕金森断言,由于其明显的政治内容,《奈菲尔提》最初写于阿门内姆哈特一世统治时期或其后不久。 [113] 辛普森称其为"......一本公然的政治小册子,旨在支持阿门内姆哈特建立的第十二王朝的新政权",阿门内姆哈特从第十一王朝的门图霍特普家族手中篡夺了王位。 [114] 在叙述性话语中,第四王朝的斯奈费鲁(Sneferu,公元前 2613-2589 年)召见了圣人和祭司奈费尔提(Neferti)。奈费尔提预言埃及将进入一个混乱的时代,这暗指的是第一中间期,但一位正义的国王--阿门尼--古埃及人很容易认出他就是阿门内哈特一世,从而恢复了昔日的辉煌。 [115] 《羔羊》和《波特》也采用了类似的模式,即由一位救世主国王将一个动荡的世界转变为一个黄金时代,尽管对于生活在罗马统治下的受众来说,救世主尚未到来。 [116]

Although written during the Twelfth dynasty, Ipuwer only survives from a Nineteenth dynasty papyrus. However, A man and his Ba is found on an original Twelfth dynasty papyrus, Papyrus Berlin 3024.[117] These two texts resemble other discourses in style, tone, and subject matter, although they are unique in that the fictional audiences are given very active roles in the exchange of dialogue.[118] In Ipuwer, a sage addresses an unnamed king and his attendants, describing the miserable state of the land, which he blames on the king's inability to uphold royal virtues. This can be seen either as a warning to kings or as a legitimization of the current dynasty, contrasting it with the supposedly turbulent period that preceded it.[119] In A man and his Ba, a man recounts for an audience a conversation with his ba (a component of the Egyptian soul) on whether to continue living in despair or to seek death as an escape from misery.[120]

虽然《Ipuwer》写于第十二王朝,但它仅存于十九王朝的纸莎草纸中。不过,《一个人和他的巴》则出现在第十二王朝的原始纸莎草纸--柏林 3024 号纸莎草纸上。 [117] 这两段文字在风格、语气和主题上与其他论述相似,但它们的独特之处在于虚构的听众在对话交流中扮演了非常积极的角色。 [118] 在《Ipuwer》中,一位圣人向一位未具名的国王及其随从讲述了这片土地的悲惨状况,并将其归咎于国王无法维护王室的美德。这既可以看作是对国王的警告,也可以看作是将当前的王朝合法化,与之前的动荡时期形成鲜明对比。 [119] 在《一个人和他的巴》中,一个人向观众讲述了他与自己的巴(埃及人灵魂的组成部分)的对话,是继续在绝望中生活,还是寻求死亡来摆脱痛苦。 [120]

Poems, songs, hymns, and afterlife texts

诗歌、歌曲、赞美诗和来世文本[edit]

胡内费尔(十九王朝)《死者之书》中的这一小场景显示,他的心脏被放在真理之羽上称量。如果他的心脏比羽毛轻,他就可以进入来世;如果不轻,他的心脏就会被阿米特吞没。

The funerary stone slab stela was first produced during the early Old Kingdom. Usually found in mastaba tombs, they combined raised-relief artwork with inscriptions bearing the name of the deceased, their official titles (if any), and invocations.[121]

墓葬石板石碑最早出现在古王国早期。石板石碑通常出现在玛斯塔巴墓穴中,石板石碑将浮雕艺术与刻有死者姓名、官职(如果有的话)和祈愿语的铭文结合在一起。 [121]

Funerary poems were thought to preserve a monarch's soul in death. The Pyramid Texts are the earliest surviving religious literature incorporating poetic verse.[122] These texts do not appear in tombs or pyramids originating before the reign of Unas (r. 2375–2345 BC), who had the Pyramid of Unas built at Saqqara.[122] The Pyramid Texts are chiefly concerned with the function of preserving and nurturing the soul of the sovereign in the afterlife.[122] This aim eventually included safeguarding both the sovereign and his subjects in the afterlife.[123] A variety of textual traditions evolved from the original Pyramid Texts: the Coffin Texts of the Middle Kingdom,[124] the so-called Book of the Dead, Litany of Ra, and Amduat written on papyri from the New Kingdom until the end of ancient Egyptian civilization.[125]

人们认为葬礼诗可以保存君主死后的灵魂。金字塔文本是现存最早的包含诗歌的宗教文献。 [122] 这些文字没有出现在乌纳斯(公元前 2375-2345 年)统治之前的墓葬或金字塔中,乌纳斯曾在萨卡拉建造了乌纳斯金字塔。 [122] 金字塔文本主要涉及在来世保护和培育君主灵魂的功能。 [122] 这一目的最终包括在来世保护君主及其臣民。 [123] 从最初的金字塔文本演变出了各种文本传统:中王国的棺木文本、 [124] 从新王国直到古埃及文明终结期间写在纸莎草纸上的所谓《亡灵书》、《拉神祷文》和《阿姆杜阿特》。 [125]

Poems were also written to celebrate kingship. For example, at the Precinct of Amun-Re at Karnak, Thutmose III (r. 1479–1425 BC) of the Eighteenth dynasty erected a stela commemorating his military victories in which the gods bless Thutmose in poetic verse and ensure for him victories over his enemies.[126] In addition to stone stelas, poems have been found on wooden writing boards used by schoolboys.[127] Besides the glorification of kings,[128] poems were written to honor various deities, and even the Nile.[129]

人们还写诗来颂扬王权。例如,第十八王朝的图特摩斯三世(Thutmose III,公元前 1479-1425 年)在卡纳克的阿蒙神辖区竖立了一块纪念其军事胜利的石碑,在石碑上,神用诗歌的形式祝福图特摩斯,并确保他战胜敌人。 [126] 除了石碑,在学生使用的木制写字板上也发现了诗歌。 [127] 除了歌颂国王, [128] 诗歌还用来歌颂各种神灵,甚至是尼罗河。 [129]

公元前 15 世纪埃及第十八王朝壁画中的盲人竖琴手

Surviving hymns and songs from the Old Kingdom include the morning greeting hymns to the gods in their respective temples.[130] A cycle of Middle-Kingdom songs dedicated to Senusret III (r. 1878–1839 BC) have been discovered at El-Lahun.[131] Erman considers these to be secular songs used to greet the pharaoh at Memphis,[132] while Simpson considers them to be religious in nature but affirms that the division between religious and secular songs is not very sharp.[131] The Harper's Song, the lyrics found on a tombstone of the Middle Kingdom and on Papyrus Harris 500 from the New Kingdom, was to be performed for dinner guests at formal banquets.[133]

现存的旧王国赞美诗和歌曲包括在各自神庙中向神灵致以清晨问候的赞美诗。 [130] 在 El-Lahun 发现了献给塞努斯雷特三世(公元前 1878-1839 年)的一组中王国歌曲。 [131] 埃尔曼认为这些歌曲是在孟菲斯迎接法老时使用的世俗歌曲, [132] 辛普森则认为这些歌曲具有宗教性质,但认为宗教歌曲和世俗歌曲之间的划分并不十分明确。 [131] 《哈珀之歌》的歌词见于中王国的墓碑和新王国的纸莎草 Harris 500 上,是在正式宴会上为晚宴宾客表演的。 [133]

During the reign of Akhenaten (r. 1353–1336 BC), the Great Hymn to the Aten—preserved in tombs of Amarna, including the tomb of Ay—was written to the Aten, the sun-disk deity given exclusive patronage during his reign.[134] Simpson compares this composition's wording and sequence of ideas to those of Psalm 104.[135]

在阿肯那顿(Akhenaten,公元前 1353-1336 年)统治时期,保存在阿玛尔纳(Amarna)墓葬(包括艾伊墓)中的《阿腾大赞美诗》是为阿肯那顿而写的,阿肯那顿是他统治时期的太阳盘神,受到他的专宠。 [134] 辛普森将这首诗的措辞和思想顺序与《诗篇》第 104 篇进行了比较。 [135]

Only a single poetic hymn in the Demotic script has been preserved.[136] However, there are many surviving examples of Late-Period Egyptian hymns written in hieroglyphs on temple walls.[137]

目前只保存了一首德谟克文字的诗歌赞美诗。 [136] 不过,在神庙墙壁上有许多用象形文字书写的晚期埃及赞美诗的现存例子。 [137]

No Egyptian love song has been dated from before the New Kingdom, these being written in Late Egyptian, although it is speculated that they existed in previous times.[138] Erman compares the love songs to the Song of Songs, citing the labels "sister" and "brother" that lovers used to address each other.[139]

新王国时期之前的埃及情歌都是用晚期埃及文写成的,因此没有一首埃及情歌被确定为新王国时期之前的作品,不过据推测,这些情歌在之前的时代就已经存在了。 [138] 埃尔曼将这些情歌与《雅歌》进行了比较,并引用了恋人们用来称呼对方的 "姐妹 "和 "兄弟"。 [139]

Private letters, model letters, and epistles

私人信件、范文和书信[edit]

石灰石制成的浮雕上的象形文字;该文字是古埃及一名小学生作为练习而书写的。他从宰相卡伊(活跃于拉美西斯二世统治时期)那里抄写了四封信。

The ancient Egyptian model letters and epistles are grouped into a single literary genre. Papyrus rolls sealed with mud stamps were used for long-distance letters, while ostraca were frequently used to write shorter, non-confidential letters sent to recipients located nearby.[140] Letters of royal or official correspondence, originally written in hieratic, were sometimes given the exalted status of being inscribed on stone in hieroglyphs.[141] The various texts written by schoolboys on wooden writing boards include model letters.[89] Private letters could be used as epistolary model letters for schoolboys to copy, including letters written by their teachers or their families.[142] However, these models were rarely featured in educational manuscripts; instead fictional letters found in numerous manuscripts were used.[143] The common epistolary formula used in these model letters was "The official A. saith to the scribe B".[144]

古埃及的模范书信和书信被归类为一种文学体裁。用泥戳密封的纸莎草纸卷用于书写远距离信件,而ostraca则经常用于书写寄给附近收信人的较短的非机密信件。 [140] 最初用象形文字书写的王室或官方信件有时被赋予了崇高的地位,即用象形文字刻在石头上。 [141] 小学生在木板上书写的各种文字包括书信范本。 [89] 私人信件可以作为书信范本供学童们临摹,包括他们的老师或家人写的信件。 [142] 不过,这些范本很少出现在教育手稿中,而是使用了大量手稿中的虚构信件。 [143] 这些书信范本中常用的书信公式是 "官员 A 对抄写员 B 说"。 [144]

The oldest-known private letters on papyrus were found in a funerary temple dating to the reign of Djedkare-Izezi (r. 2414–2375 BC) of the Fifth dynasty.[145] More letters are dated to the Sixth dynasty, when the epistle subgenre began.[146] The educational text Book of Kemit, dated to the Eleventh dynasty, contains a list of epistolary greetings and a narrative with an ending in letter form and suitable terminology for use in commemorative biographies.[147] Other letters of the early Middle Kingdom have also been found to use epistolary formulas similar to the Book of Kemit.[148] The Heqanakht papyri, written by a gentleman farmer, date to the Eleventh dynasty and represent some of the lengthiest private letters known to have been written in ancient Egypt.[69]

纸莎草纸上已知最古老的私人信件是在一座葬神庙中发现的,可以追溯到第五王朝的杰卡雷-伊泽兹(Djedkare-Izezi,公元前 2414-2375 年)统治时期。 [145] 更多信件的年代可追溯到第六王朝,那时书信这一亚体裁开始出现。 [146] 《凯米特书》(Book of Kemit)是第十一王朝的教育文本,其中包含书信问候语列表和以书信形式结尾的叙述,以及适合用于纪念性传记的术语。 [147] 还发现中王国早期的其他书信也使用了与《凯米特书》类似的书信格式。 [148] 《Heqanakht 纸莎草纸》由一位绅士农夫撰写,可追溯到第十一王朝,是古埃及已知最长的私人书信。 [69]

During the late Middle Kingdom, greater standardization of the epistolary formula can be seen, for example in a series of model letters taken from dispatches sent to the Semna fortress of Nubia during the reign of Amenemhat III (r. 1860–1814 BC).[149] Epistles were also written during all three dynasties of the New Kingdom.[150] While letters to the dead had been written since the Old Kingdom, the writing of petition letters in epistolary form to deities began in the Ramesside Period, becoming very popular during the Persian and Ptolemaic periods.[151]

在中王国晚期,书信格式更加标准化,例如,在阿门内姆哈特三世(Amenemhat III,公元前 1860-1814 年)统治时期,从发往努比亚塞姆纳要塞的信件中摘录了一系列书信范本。 [149] 新王国的三个朝代都有书信。 [150] 虽然给死者的信从古王国时期就开始写了,但以书信形式写给神灵的请愿信始于拉美塞德时期,在波斯和托勒密时期变得非常流行。 [151]

The epistolary Satirical Letter of Papyrus Anastasi I written during the Nineteenth dynasty was a pedagogical and didactic text copied on numerous ostraca by schoolboys.[152] Wente describes the versatility of this epistle, which contained "proper greetings with wishes for this life and the next, the rhetoric composition, interpretation of aphorisms in wisdom literature, application of mathematics to engineering problems and the calculation of supplies for an army, and the geography of western Asia".[153] Moreover, Wente calls this a "polemical tractate" that counsels against the rote, mechanical learning of terms for places, professions, and things; for example, it is not acceptable to know just the place names of western Asia, but also important details about its topography and routes.[153] To enhance the teaching, the text employs sarcasm and irony.[153]

写于十九王朝时期的纸莎草《阿纳斯塔西一世讽刺信》是一份教学和说教文本,被学生抄写在大量的纸莎草上。 [152] 温特描述了这封书信的多功能性,其中包含 "对今生和来世的适当问候和祝愿、修辞写作、智慧文学箴言的解释、数学在工程问题上的应用和军队补给的计算,以及西亚地理"。 [153] 此外,温特称这是一部 "论辩性的小册子",劝告人们不要死记硬背、机械地学习有关地方、职业和事物的术语;例如,不能只知道西亚的地名,还要知道有关其地形和路线的重要细节。 [153] 为了增强教学效果,课文采用了讽刺和挖苦的手法。 [153]

Biographical and autobiographical texts

传记和自传文本[edit]

Catherine Parke, Professor Emerita of English and Women's Studies at the University of Missouri in Columbia, Missouri, writes that the earliest "commemorative inscriptions" belong to ancient Egypt and date to the 3rd millennium BC.[154] She writes: "In ancient Egypt the formulaic accounts of Pharaoh's lives praised the continuity of dynastic power. Although typically written in the first person, these pronouncements are public, general testimonials, not personal utterances."[155] She adds that as in these ancient inscriptions, the human urge to "...celebrate, commemorate, and immortalize, the impulse of life against death", is the aim of biographies written today.[155]

密苏里州哥伦比亚市密苏里大学英语和妇女研究名誉教授凯瑟琳-帕克(Catherine Parke)写道,最早的 "纪念铭文 "属于古埃及,可以追溯到公元前三千年。 [154] 她写道:"在古埃及,法老生平的公式化记载赞扬了王朝权力的连续性。虽然这些记载通常以第一人称书写,但它们都是公开的、一般性的见证,而不是个人的言论"。 [155] 她补充说,与这些古代碑文一样,人类"......颂扬、纪念和不朽,生命对抗死亡的冲动 "的冲动,也是今天撰写传记的目的。 [155]

巴(Ba)的墓碑(坐着,一边闻着圣莲一边接受祭品);巴的儿子梅斯(Mes)和妻子伊尼(Iny)也坐着。奠酒者的身份不明。石碑的年代为新王国时期第十八王朝。

Olivier Perdu, a professor of Egyptology at the Collège de France, states that biographies did not exist in ancient Egypt, and that commemorative writing should be considered autobiographical.[156] Edward L. Greenstein, Professor of Bible at the Tel Aviv University and Bar-Ilan University, disagrees with Perdu's terminology, stating that the ancient world produced no "autobiographies" in the modern sense, and these should be distinguished from 'autobiographical' texts of the ancient world.[157] However, both Perdu and Greenstein assert that autobiographies of the ancient Near East should not be equated with the modern concept of autobiography.[158]

法兰西学院埃及学教授奥利维耶-佩尔杜(Olivier Perdu)指出,古埃及不存在传记,纪念性文字应被视为自传。 [156] 特拉维夫大学和巴伊兰大学圣经教授爱德华-格林斯坦(Edward L. Greenstein)不同意佩尔杜的说法,他指出古代世界没有现代意义上的 "自传",这些自传应与古代世界的 "自传 "文本区分开来。 [157] 不过,佩尔杜和格林斯坦都认为,古代近东的自传不应等同于现代的自传概念。 [158]

In her discussion of the Ecclesiastes of the Hebrew Bible, Jennifer Koosed, associate professor of religion at Albright College, explains that there is no solid consensus among scholars as to whether true biographies or autobiographies existed in the ancient world.[159] One of the major scholarly arguments against this theory is that the concept of individuality did not exist until the European Renaissance, prompting Koosed to write "...thus autobiography is made a product of European civilization: Augustine begat Rosseau begat Henry Adams, and so on".[159] Koosed asserts that the use of first-person "I" in ancient Egyptian commemorative funerary texts should not be taken literally since the supposed author is already dead. Funerary texts should be considered biographical instead of autobiographical.[158] Koosed cautions that the term "biography" applied to such texts is problematic, since they also usually describe the deceased person's experiences of journeying through the afterlife.[158]

奥尔布赖特学院宗教学副教授詹妮弗-科塞斯(Jennifer Koosed)在讨论《希伯来圣经》中的传道书时解释说,对于古代世界是否存在真正的传记或自传,学者们并没有达成一致意见。 [159] 反对这一理论的主要学术论据之一是,直到欧洲文艺复兴时期才有了个性的概念,这促使 Koosed 写道:"......因此,自传被认为是欧洲文明的产物:奥古斯丁生罗索,罗索生亨利-亚当斯,以此类推"。 [159] 科塞斯断言,古埃及纪念性殡葬文本中第一人称 "我 "的使用不应按字面理解,因为假定的作者已经去世。墓葬文献应被视为传记而非自传。 [158] Koosed 提醒说,"传记 "一词用于此类文本是有问题的,因为它们通常也描述死者在来世的旅行经历。 [158]

Beginning with the funerary stelas for officials of the late Third dynasty, small amounts of biographical detail were added next to the deceased men's titles.[160] However, it was not until the Sixth dynasty that narratives of the lives and careers of government officials were inscribed.[161] Tomb biographies became more detailed during the Middle Kingdom, and included information about the deceased person's family.[162] The vast majority of autobiographical texts are dedicated to scribal bureaucrats, but during the New Kingdom some were dedicated to military officers and soldiers.[163] Autobiographical texts of the Late Period place a greater stress upon seeking help from deities than acting righteously to succeed in life.[164] Whereas earlier autobiographical texts exclusively dealt with celebrating successful lives, Late Period autobiographical texts include laments for premature death, similar to the epitaphs of ancient Greece.[165]

从第三王朝晚期的官员墓碑开始,在死者的头衔旁边添加了少量的传记细节。 [160] 然而,直到第六王朝,才开始刻写政府官员的生平和职业生涯。 [161] 到了中土时期,墓志变得更加详细,还包括了有关死者家庭的信息。 [162] 绝大多数自传都是为文士官僚撰写的,但在新王国时期,有些自传是为军官和士兵撰写的。 [163] 晚期的自传体文章更强调寻求神灵的帮助,而不是通过正直的行为获得人生的成功。 [164] 早期的自传体文章只涉及对成功人生的赞美,而晚期自传体文章则包括对早逝的哀叹,类似于古希腊的墓志铭。 [165]

Decrees, chronicles, king lists, and histories

法令、编年史、国王名单和历史[edit]

卡纳克法老图特摩斯三世年鉴

Modern historians consider that some biographical—or autobiographical—texts are important historical documents.[166] For example, the biographical stelas of military generals in tomb chapels built under Thutmose III provide much of the information known about the wars in Syria and Canaan.[167] However, the annals of Thutmose III, carved into the walls of several monuments built during his reign, such as those at Karnak, also preserve information about these campaigns.[168] The annals of Ramesses II (r. 1279–1213 BC), recounting the Battle of Kadesh against the Hittites include, for the first time in Egyptian literature, a narrative epic poem, distinguished from all earlier poetry that served to celebrate and instruct.[169]

现代历史学家认为,一些传记--或自传--文本是重要的历史文献。 [166] 例如,图特摩斯三世时期建造的墓室中的军事将领传记石碑提供了有关叙利亚和迦南战争的大量信息。 [167] 不过,刻在卡纳克等几座在位期间建造的纪念碑墙壁上的图特摩斯三世年鉴也保存了有关这些战役的信息。 [168] 拉美西斯二世(Ramesses II,公元前 1279-1213 年)的年鉴记述了对赫梯人的卡德什战役,其中包括埃及文学史上首次出现的叙事史诗,有别于早期所有歌颂和教诲的诗歌。 [169]

Other documents useful for investigating Egyptian history are ancient lists of kings found in terse chronicles, such as the Fifth dynasty Palermo stone.[170] These documents legitimated the contemporary pharaoh's claim to sovereignty.[171] Throughout ancient Egyptian history, royal decrees recounted the deeds of ruling pharaohs.[172] For example, the Nubian pharaoh Piye (r. 752–721 BC), founder of the Twenty-fifth Dynasty, had a stela erected and written in classical Middle Egyptian that describes with unusual nuances and vivid imagery his successful military campaigns.[173]

其他有助于研究埃及历史的文献是简明编年史中的古代国王名单,如第五王朝的巴勒莫石碑。 [170] 这些文件使当代法老的主权要求合法化。 [171] 在整个古埃及历史中,王室法令都记述了执政法老的事迹。 [172] 例如,努比亚法老皮耶(公元前 752-721 年)是第二十五王朝的创始人,他用古典中古埃及文书写了一块石碑,以不同寻常的细微差别和生动的形象描述了他成功的军事行动。 [173]

An Egyptian historian, known by his Greek name as Manetho (c. 3rd century BC), was the first to compile a comprehensive history of Egypt.[174] Manetho was active during the reign of Ptolemy II (r. 283–246 BC) and used The Histories by the Greek Herodotus (c. 484 BC–c. 425 BC) as his main source of inspiration for a history of Egypt written in Greek.[174] However, the primary sources for Manetho's work were the king list chronicles of previous Egyptian dynasties.[171]

埃及历史学家,希腊名字叫马奈托(Manetho,约公元前 3 世纪),是第一位编纂全面埃及历史的人。 [174] 马奈托活跃于托勒密二世(公元前 283-246 年)统治时期,他以希腊人希罗多德(约公元前 484 年-约公元前 425 年)的《历史》为主要灵感来源,用希腊语撰写埃及历史。 [174] 然而,马奈托作品的主要来源是埃及历代王朝的王表编年史。 [171]

Tomb and temple graffiti 古墓和寺庙涂鸦[edit]

托勒密王朝时期建造的康翁博神庙中的犬形艺术涂鸦

Fischer-Elfert distinguishes ancient Egyptian graffiti writing as a literary genre.[175] During the New Kingdom, scribes who traveled to ancient sites often left graffiti messages on the walls of sacred mortuary temples and pyramids, usually in commemoration of these structures.[176] Modern scholars do not consider these scribes to have been mere tourists, but pilgrims visiting sacred sites where the extinct cult centers could be used for communicating with the gods.[177] There is evidence from an educational ostracon found in the tomb of Senenmut (TT71) that formulaic graffiti writing was practiced in scribal schools.[177] In one graffiti message, left at the mortuary temple of Thutmose III at Deir el-Bahri, a modified saying from The Maxims of Ptahhotep is incorporated into a prayer written on the temple wall.[178] Scribes usually wrote their graffiti in separate clusters to distinguish their graffiti from others'.[175] This led to competition among scribes, who would sometimes denigrate the quality of graffiti inscribed by others, even ancestors from the scribal profession.[175]

Fischer-Elfert 将古埃及的涂鸦写作区分为一种文学体裁。 [175] 在新王国时期,到古代遗址旅游的文士经常在神圣的停尸神庙和金字塔的墙壁上留下涂鸦信息,通常是为了纪念这些建筑。 [176] 现代学者认为这些文士并不是单纯的游客,而是前往圣地的朝圣者,在那里,已消失的崇拜中心可以用来与神沟通。 [177] 从塞嫩穆特(Senenmut)墓(TT71)中发现的一个教育用的浮雕中可以看出,文士学校中存在着公式化的涂鸦书写。 [177] 在 Deir el-Bahri 的图特摩斯三世停尸庙留下的一幅涂鸦中,《普塔霍特普的格言》中的一句话被修改后融入了庙墙上的祈祷词中。 [178] 文士们通常把自己的涂鸦写在不同的组中,以区别于其他人的涂鸦。 [175] 这导致了抄写员之间的竞争,他们有时会诋毁他人所刻涂鸦的质量,甚至是抄写员行业的祖先。 [175]

Legacy, translation and interpretation

遗产、翻译和口译[edit]

After the Copts converted to Christianity in the first centuries AD, their Coptic literature became separated from the pharaonic and Hellenistic literary traditions.[179] Nevertheless, scholars speculate that ancient Egyptian literature, perhaps in oral form, influenced Greek and Arabic literature. Parallels are drawn between the Egyptian soldiers sneaking into Jaffa hidden in baskets to capture the city in the story The Taking of Joppa and the Mycenaean Greeks sneaking into Troy inside the Trojan Horse.[180] The Taking of Joppa has also been compared to the Arabic story of Ali Baba in One Thousand and One Nights.[181] It has been conjectured that Sinbad the Sailor may have been inspired by the pharaonic Tale of the Shipwrecked Sailor.[182] Some Egyptian literature was commented on by scholars of the ancient world. For example, the Jewish Roman historian Josephus (37–c. 100 AD) quoted and provided commentary on Manetho's historical texts.[183]

公元一世纪,科普特人皈依基督教后,他们的科普特文学与法老文学和希腊文学传统分离开来。 [179] 不过,学者们推测,古埃及文学,也许是口头形式的古埃及文学,影响了希腊和阿拉伯文学。在《攻占约帕城》(The Taking of Joppa)故事中,埃及士兵藏在篮子里潜入雅法攻城,而迈锡尼希腊人则在特洛伊木马中潜入特洛伊,这两者之间存在相似之处。 [180] 《攻占约帕城》还被比作阿拉伯语《一千零一夜》中的阿里巴巴故事。 [181] 有人猜测,《水手辛巴达》的灵感可能来自法老时代的《遇难水手的故事》。 [182] 古代世界的学者对一些埃及文学作品进行了评论。例如,犹太罗马历史学家约瑟夫(Josephus,37-约公元 100 年)引用了马奈托的历史文献并对其进行了评论。 [183]

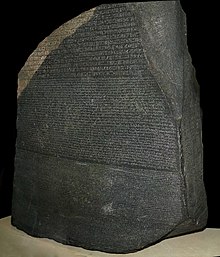

大英博物馆中的三语罗塞塔石碑

The most recently carved hieroglyphic inscription of ancient Egypt known today is found in a temple of Philae, dated precisely to 394 AD during the reign of Theodosius I (r. 379–395 AD).[184] In the 4th century AD, the Hellenized Egyptian Horapollo compiled a survey of almost two hundred Egyptian hieroglyphs and provided his interpretation of their meanings, although his understanding was limited and he was unaware of the phonetic uses of each hieroglyph.[185] This survey was apparently lost until 1415, when the Italian Cristoforo Buondelmonti acquired it at the island of Andros.[185] Athanasius Kircher (1601–1680) was the first in Europe to realize that Coptic was a direct linguistic descendant of ancient Egyptian.[185] In his Oedipus Aegyptiacus, he made the first concerted European effort to interpret the meaning of Egyptian hieroglyphs, albeit based on symbolic inferences.[185]

目前已知的最新的古埃及象形文字碑文是在菲莱神庙中发现的,其确切年代为狄奥多西一世(公元 379-395 年)统治时期的公元 394 年。 [184] 公元 4 世纪,希腊化的埃及人霍拉波罗(Horapollo)汇编了近 200 个埃及象形文字的调查表,并提供了他对这些象形文字含义的解释,尽管他的理解有限,而且不知道每个象形文字的语音用途。 [185] 这份调查表显然已经遗失,直到 1415 年,意大利人克里斯托弗罗-布昂德尔蒙蒂在安德罗斯岛获得了这份调查表。 [185] 亚他那修-基切(1601-1680 年)是欧洲第一个认识到科普特语是古埃及语的直系后裔的人。 [185] 在他的《俄狄浦斯-埃及》(Oedipus Aegyptiacus)一书中,他第一次协同欧洲人努力解释埃及象形文字的含义,尽管是基于象征性的推论。 [185]

It was not until 1799, with the Napoleonic discovery of a trilingual (i.e. hieroglyphic, Demotic, Greek) stela inscription on the Rosetta Stone, that modern scholars had the resources to decipher Egyptian texts.[186] The key breakthroughs were made more than twenty years later, in the work of Jean-François Champollion in deciphering hieroglyphs and Thomas Young in deciphering Demotic.[187] By the time of Champollion's death in 1832, it was possible to discern the general sense of Egyptian texts.[188] The first scholar able to read an Egyptian text in full was Emmanuel de Rougé, who published the first translations of Egyptian literary texts in 1856.[189]

直到 1799 年,拿破仑在罗塞塔石碑上发现了三语(即象形文字、底莫西语和希腊语)石碑铭文,现代学者才有了破译埃及文字的资源。 [186] 二十多年后,让-弗朗索瓦-尚波利昂(Jean-François Champollion)和托马斯-扬(Thomas Young)分别在象形文字破译和底莫提文破译方面取得了关键性突破。 [187] 1832年尚波利昂去世时,人们已经能够辨别埃及文字的一般意义。 [188] 第一位能够完整阅读埃及文字的学者是埃马纽埃尔-德-鲁热(Emmanuel de Rougé),他于 1856 年出版了第一批埃及文学文本的译本。 [189]

Before the 1970s, scholarly consensus was that ancient Egyptian literature—although sharing similarities with modern literary categories—was not an independent discourse, uninfluenced by the ancient sociopolitical order.[190] However, from the 1970s onwards, a growing number of historians and literary scholars have questioned this theory.[191] While scholars before the 1970s treated ancient Egyptian literary works as viable historical sources that accurately reflected the conditions of this ancient society, scholars now caution against this approach.[192] Scholars are increasingly using a multifaceted hermeneutic approach to the study of individual literary works, in which not only the style and content, but also the cultural, social and historical context of the work are taken into account.[191] Individual works can then be used as case studies for reconstructing the main features of ancient Egyptian literary discourse.[191]

20 世纪 70 年代以前,学者们一致认为,古埃及文学虽然与现代文学范畴有相似之处,但并非独立的话语,不受古代社会政治秩序的影响。 [190] 然而,从 20 世纪 70 年代起,越来越多的历史学家和文学学者对这一理论提出了质疑。 [191] 20 世纪 70 年代以前的学者将古埃及文学作品视为可行的历史资料,认为它们准确地反映了这一古代社会的状况,而现在的学者则对这种做法持谨慎态度。 [192] 学者们越来越多地采用多方面的诠释学方法来研究单个文学作品,在这种方法中,不仅要考虑作品的风格和内容,还要考虑作品的文化、社会和历史背景。 [191] 然后,可以将单个作品作为案例研究,重建古埃及文学话语的主要特征。 [191]

Notes 说明[edit]

- ^ Foster 2001, p. xx.

Foster 2001 年,第 xx 页。 - ^ Parkinson 2002, pp. 64–66.

Parkinson 2002 年,第 64-66 页。 - ^ Forman & Quirke 1996, p. 26.

Forman & Quirke 1996 年,第 26 页。 - ^ Wilson 2003, pp. 7–10; Forman & Quirke 1996, pp. 10–12; Wente 1990, p. 2; Allen 2000, pp. 1–2, 6.

Wilson 2003 年,第 7-10 页;Forman & Quirke 1996 年,第 10-12 页;Wente 1990 年,第 2 页;Allen 2000 年,第 1-2 和 6 页。 - ^ Wilson 2003, p. 28; Forman & Quirke 1996, p. 13; Allen 2000, p. 3.

Wilson 2003 年,第 28 页;Forman & Quirke 1996 年,第 13 页;Allen 2000 年,第 3 页。 - ^ Forman & Quirke 1996, p. 13; for similar examples, see Allen (2000: 3) and Erman (2005: xxxv-xxxvi).

Forman & Quirke 1996, 第 13 页;类似例子见 Allen (2000: 3) 和 Erman (2005: xxxv-xxxvi) 。 - ^ Wilkinson 2000, pp. 23–24; Wilson 2004, p. 11; Gardiner 1915, p. 72.

Wilkinson 2000 年,第 23-24 页;Wilson 2004 年,第 11 页;Gardiner 1915 年,第 72 页。 - ^ Wilson 2003, pp. 22, 47; Forman & Quirke 1996, pp. 10; Wente 1990, p. 2; Parkinson 2002, p. 73.

Wilson 2003, 第 22、47 页;Forman & Quirke 1996, 第 10 页;Wente 1990, 第 2 页;Parkinson 2002, 第 73 页。 - ^ Forman & Quirke 1996, p. 10.

Forman & Quirke 1996 年,第 10 页。 - ^ Wilson 2003, pp. 63–64.

Wilson 2003 年,第 63-64 页。 - ^ Jump up to: a b c Wilson 2003, p. 71; Forman & Quirke 1996, pp. 101–103.

Wilson 2003 年,第 71 页;Forman & Quirke 1996 年,第 101-103 页。 - ^ Erman 2005, p. xxxvii; Simpson 1972, pp. 8–9; Forman & Quirke 1996, p. 19; Allen 2000, p. 6.

Erman 2005 年,第 xxxvii 页;Simpson 1972 年,第 8-9 页;Forman & Quirke 1996 年,第 19 页;Allen 2000 年,第 6 页。 - ^ Jump up to: a b Forman & Quirke 1996, p. 19.

Forman & Quirke 1996 年,第 19 页。 - ^ Wilson 2003, pp. 22–23.

Wilson 2003 年,第 22-23 页。 - ^ Wilson 2003, pp. 22–23, 91–92; Parkinson 2002, p. 73; Wente 1990, pp. 1–2; Spalinger 1990, p. 297; Allen 2000, p. 6.

Wilson 2003 年,第 22-23 页,第 91-92 页;Parkinson 2002 年,第 73 页;Wente 1990 年,第 1-2 页;Spalinger 1990 年,第 297 页;Allen 2000 年,第 6 页。 - ^ Parkinson 2002, pp. 73–74; Forman & Quirke 1996, p. 19.

Parkinson 2002, 第 73-74 页;Forman & Quirke 1996, 第 19 页。 - ^ Jump up to: a b Forman & Quirke 1996, p. 17.

Forman & Quirke 1996 年,第 17 页。 - ^ Forman & Quirke 1996, pp. 17–19, 169; Allen 2000, p. 6.

Forman & Quirke 1996 年,第 17-19 页,第 169 页;Allen 2000 年,第 6 页。 - ^ Forman & Quirke 1996, pp. 19, 169; Allen 2000, p. 6; Simpson 1972, pp. 8–9; Erman 2005, pp. xxxvii, xlii; Foster 2001, p. xv.

Forman & Quirke 1996 年,第 19、169 页;Allen 2000 年,第 6 页;Simpson 1972 年,第 8-9 页;Erman 2005 年,第 xxxvii、xlii 页;Foster 2001 年,第 xv 页。 - ^ Jump up to: a b Wente 1990, p. 4.

Wente 1990 年,第 4 页。 - ^ Jump up to: a b Wente 1990, pp. 4–5.

Wente 1990 年,第 4-5 页。 - ^ Allen 2000, p. 5; Foster 2001, p. xv; see also Wente 1990, pp. 5–6 for a wooden writing board example.

Allen 2000 年,第 5 页;Foster 2001 年,第 xv 页;另见 Wente 1990 年,第 5-6 页,木制写字板的例子。 - ^ Jump up to: a b c Forman & Quirke 1996, p. 169.

Forman & Quirke 1996 年,第 169 页。 - ^ Jump up to: a b Quirke 2004, p. 14.

Quirke 2004 年,第 14 页。 - ^ Wente 1990, pp. 2–3; Tait 2003, pp. 9–10.

Wente 1990 年,第 2-3 页;Tait 2003 年,第 9-10 页。 - ^ Wente 1990, pp. 2–3.

Wente 1990 年,第 2-3 页。 - ^ Jump up to: a b c Tait 2003, pp. 9–10.

Tait 2003 年,第 9-10 页。 - ^ Jump up to: a b Wilson 2003, pp. 91–93.

Wilson 2003 年,第 91-93 页。 - ^ Wilson 2003, pp. 91–93; see also Wente 1990, pp. 132–133.

Wilson 2003 年,第 91-93 页;另见 Wente 1990 年,第 132-133 页。 - ^ Tait 2003, p. 10; see also Parkinson 2002, pp. 298–299.

Tait 2003 年,第 10 页;另见 Parkinson 2002 年,第 298-299 页。 - ^ Jump up to: a b c Fischer-Elfert 2003, p. 121.

Fischer-Elfert 2003 年,第 121 页。 - ^ Simpson 1972, pp. 3–4; Foster 2001, pp. xvii–xviii.

Simpson 1972 年,第 3-4 页;Foster 2001 年,第 xvi-xviii 页。 - ^ Jump up to: a b c Allen 2000, p. 1.

Allen 2000 年,第 1 页。 - ^ Allen 2000, p. 1; Fischer-Elfert 2003, p. 119; Erman 2005, pp. xxv–xxvi.

Allen 2000 年,第 1 页;Fischer-Elfert 2003 年,第 119 页;Erman 2005 年,第 xxv-xxvi 页。 - ^ Allen 2000, p. 1; Wildung 2003, p. 61.

Allen 2000 年,第 1 页;Wildung 2003 年,第 61 页。 - ^ Allen 2000, p. 6.

Allen 2000 年,第 6 页。 - ^ Allen 2000, pp. 1, 5–6; Wildung 2003, p. 61; Erman 2005, pp. xxv–xxvii; Lichtheim 1980, p. 4.

Allen 2000 年,第 1、5-6 页;Wildung 2003 年,第 61 页;Erman 2005 年,第 xxv-xxvii 页;Lichtheim 1980 年,第 4 页。 - ^ Allen 2000, p. 5; Erman 2005, pp. xxv–xxvii; Lichtheim 1980, p. 4.

Allen 2000 年,第 5 页;Erman 2005 年,第 xxv-xxvii 页;Lichtheim 1980 年,第 4 页。 - ^ Wildung 2003, p. 61.

Wildung 2003 年,第 61 页。 - ^ Wente 1990, pp. 6–7; see also Wilson 2003, pp. 19–20, 96–97; Erman 2005, pp. xxvii–xxviii.

Wente 1990 年,第 6-7 页;另见 Wilson 2003 年,第 19-20 页,第 96-97 页;Erman 2005 年,第 xxvi-xxviii 页。 - ^ Wilson 2003, p. 96.

Wilson 2003 年,第 96 页。 - ^ Wente 1990, pp. 7–8.

Wente 1990 年,第 7-8 页。 - ^ Wente 1990, pp. 7–8; Parkinson 2002, pp. 66–67.

Wente 1990 年,第 7-8 页;Parkinson 2002 年,第 66-67 页。 - ^ Wilson 2003, pp. 23–24.

Wilson 2003 年,第 23-24 页。 - ^ Wilson 2003, p. 95.

Wilson 2003 年,第 95 页。 - ^ Wilson 2003, pp. 96–98.

Wilson 2003 年,第 96-98 页。 - ^ Parkinson 2002, pp. 66–67.

Parkinson 2002 年,第 66-67 页。 - ^ Fischer-Elfert 2003, pp. 119–121; Parkinson 2002, p. 50.

Fischer-Elfert 2003 年,第 119-121 页;Parkinson 2002 年,第 50 页。 - ^ Wilson 2003, pp. 97–98; see Parkinson 2002, pp. 53–54; see also Fischer-Elfert 2003, pp. 119–121.

Wilson 2003 年,第 97-98 页;见 Parkinson 2002 年,第 53-54 页;另见 Fischer-Elfert 2003 年,第 119-121 页。 - ^ Parkinson 2002, pp. 54–55; see also Morenz 2003, p. 104.

Parkinson 2002 年,第 54-55 页;另见 Morenz 2003 年,第 104 页。 - ^ Jump up to: a b Simpson 1972, pp. 5–6.

Simpson 1972 年,第 5-6 页。 - ^ Fischer-Elfert 2003, p. 122.

Fischer-Elfert 2003 年,第 122 页。 - ^ Parkinson 2002, pp. 78–79; for pictures (with captions) of Egyptian miniature funerary models of boats with men reading papyrus texts aloud, see Forman & Quirke 1996, pp. 76–77, 83.

Parkinson 2002 年,第 78-79 页;关于埃及微型船葬模型的图片(带说明),以及男子朗读纸莎草文本的图片,见 Forman 和 Quirke 1996 年,第 76-77 页和第 83 页。 - ^ Jump up to: a b c Parkinson 2002, pp. 78–79.

Parkinson 2002 年,第 78-79 页。 - ^ Wilson 2003, p. 93.

Wilson 2003 年,第 93 页。 - ^ Jump up to: a b Parkinson 2002, pp. 80–81.

Parkinson 2002 年,第 80-81 页。 - ^ Jump up to: a b Forman & Quirke 1996, pp. 51–56, 62–63, 68–72, 111–112; Budge 1972, pp. 240–243.

Forman & Quirke 1996 年,第 51-56, 62-63, 68-72, 111-112 页;Budge 1972 年,第 240-243 页。 - ^ Parkinson 2002, p. 70.

Parkinson 2002 年,第 70 页。 - ^ Wente 1990, pp. 1, 9, 132–133.

Wente 1990 年,第 1、9、132-133 页。 - ^ Wente 1990, p. 9.

Wente 1990 年,第 9 页。 - ^ Parkinson 2002, pp. 45–46, 49–50, 55–56; Morenz 2003, p. 102; see also Simpson 1972, pp. 3–6 and Erman 2005, pp. xxiv–xxv.

Parkinson 2002, 第 45-46, 49-50, 55-56 页;Morenz 2003, 第 102 页;另见 Simpson 1972, 第 3-6 页和 Erman 2005, 第 xxiv-xxv 页。 - ^ Jump up to: a b Morenz 2003, p. 102.

Morenz 2003 年,第 102 页。 - ^ Parkinson 2002, pp. 45–46, 49–50, 55–56; Morenz 2003, p. 102.

Parkinson 2002 年,第 45-46 页,第 49-50 页,第 55-56 页;Morenz 2003 年,第 102 页。 - ^ Jump up to: a b Parkinson 2002, pp. 47–48.

Parkinson 2002 年,第 47-48 页。 - ^ Parkinson 2002, pp. 45–46; Morenz 2003, pp. 103–104.

Parkinson 2002 年,第 45-46 页;Morenz 2003 年,第 103-104 页。 - ^ Parkinson 2002, p. 46.

Parkinson 2002 年,第 46 页。 - ^ Parkinson 2002, pp. 46–47; see also Morenz 2003, pp. 101–102.

Parkinson 2002 年,第 46-47 页;另见 Morenz 2003 年,第 101-102 页。 - ^ Morenz 2003, pp. 104–107.

Morenz 2003 年,第 104-107 页。 - ^ Jump up to: a b Wente 1990, pp. 54–55, 58–63.

Wente 1990 年,第 54-55 页、第 58-63 页。 - ^ Parkinson 2002, pp. 75–76.

Parkinson 2002 年,第 75-76 页。 - ^ Parkinson 2002, pp. 75–76; Fischer-Elfert 2003, p. 120.

Parkinson 2002 年,第 75-76 页;Fischer-Elfert 2003 年,第 120 页。 - ^ Tait 2003, pp. 12–13.

Tait 2003 年,第 12-13 页。 - ^ Parkinson 2002, pp. 238–239.

Parkinson 2002 年,第 238-239 页。 - ^ Wente 1990, p. 7.

Wente 1990 年,第 7 页。 - ^ Wente 1990, pp. 17–18.

Wente 1990 年,第 17-18 页。 - ^ Fischer-Elfert 2003, pp. 122–123; Simpson 1972, p. 3.

Fischer-Elfert 2003 年,第 122-123 页;Simpson 1972 年,第 3 页。 - ^ Fischer-Elfert 2003, pp. 122–123; Simpson 1972, pp. 5–6; Parkinson 2002, p. 110.

Fischer-Elfert 2003 年,第 122-123 页;Simpson 1972 年,第 5-6 页;Parkinson 2002 年,第 110 页。 - ^ Parkinson 2002, pp. 108–109.

Parkinson 2002 年,第 108-109 页。 - ^ Foster 2001, pp. xv–xvi.

Foster 2001 年,第 xv-xvi 页。 - ^ Foster 2001, p. xvi.

Foster 2001 年,第 xvi 页。 - ^ Jump up to: a b c d Parkinson 2002, p. 110.

Parkinson 2002 年,第 110 页。 - ^ Jump up to: a b Parkinson 2002, pp. 110, 235.

Parkinson 2002 年,第 110 和 235 页。 - ^ Parkinson 2002, pp. 236–237.

Parkinson 2002 年,第 236-237 页。 - ^ Erman 2005, p. 54.

Erman 2005 年,第 54 页。 - ^ Loprieno 1996, p. 217.

Loprieno 1996 年,第 217 页。 - ^ Simpson 1972, p. 6; see also Parkinson 2002, pp. 236–238.

Simpson 1972 年,第 6 页;另见 Parkinson 2002 年,第 236-238 页。 - ^ Parkinson 2002, pp. 237–238.

Parkinson 2002 年,第 237-238 页。 - ^ Parkinson 2002, pp. 313–319; Simpson 1972, pp. 159–200, 241–268.

Parkinson 2002 年,第 313-319 页;Simpson 1972 年,第 159-200 页,第 241-268 页。 - ^ Jump up to: a b c d Parkinson 2002, pp. 235–236.

Parkinson 2002 年,第 235-236 页。 - ^ Parkinson 2002, pp. 313–315; Simpson 1972, pp. 159–177.

Parkinson 2002 年,第 313-315 页;Simpson 1972 年,第 159-177 页。 - ^ Parkinson 2002, pp. 318–319.

Parkinson 2002 年,第 318-319 页。 - ^ Parkinson 2002, pp. 313–314, 315–317; Simpson 1972, pp. 180, 193.

Parkinson 2002, 第 313-314, 315-317 页;Simpson 1972, 第 180, 193 页。 - ^ Simpson 1972, p. 241.

Simpson 1972 年,第 241 页。 - ^ Parkinson 2002, pp. 295–296.

Parkinson 2002 年,第 295-296 页。 - ^ Jump up to: a b c Parkinson 2002, p. 109.

Parkinson 2002 年,第 109 页。 - ^ Fischer-Elfert 2003, p. 120.

Fischer-Elfert 2003 年,第 120 页。 - ^ Parkinson 2002, pp. 294–299; Simpson 1972, pp. 15–76; Erman 2005, pp. 14–52.

Parkinson 2002 年,第 294-299 页;Simpson 1972 年,第 15-76 页;Erman 2005 年,第 14-52 页。 - ^ Simpson 1972, pp. 77–158; Erman 2005, pp. 150–175.

Simpson 1972 年,第 77-158 页;Erman 2005 年,第 150-175 页。 - ^ Gozzoli 2006, pp. 247–249; for another source on the Famine Stela, see Lichtheim 1980, pp. 94–95.

Gozzoli 2006 年,第 247-249 页;关于饥荒石碑的另一个资料来源,见 Lichtheim 1980 年,第 94-95 页。 - ^ Jump up to: a b Morenz 2003, pp. 102–104.

Morenz 2003 年,第 102-104 页。 - ^ Parkinson 2002, pp. 297–298.

Parkinson 2002 年,第 297-298 页。 - ^ Simpson 1972, p. 57.

Simpson 1972 年,第 57 页。 - ^ Simpson 1972, p. 50; see also Foster 2001, p. 8.

Simpson 1972 年,第 50 页;另见 Foster 2001 年,第 8 页。 - ^ Foster 2001, p. 8.

Foster 2001 年,第 8 页。 - ^ Simpson 1972, pp. 81, 85, 87, 142; Erman 2005, pp. 174–175.

Simpson 1972 年,第 81、85、87、142 页;Erman 2005 年,第 174-175 页。 - ^ Jump up to: a b Simpson 1972, p. 57 states that there are two Middle-Kingdom manuscripts for Sinuhe, while the updated work of Parkinson 2002, pp. 297–298 mentions five manuscripts.

Simpson 1972 年的第 57 页指出,有两份中王国关于西奴河的手稿,而 Parkinson 2002 年的最新著作第 297-298 页提到了五份手稿。 - ^ Simpson 1972, pp. 6–7; Parkinson 2002, pp. 110, 193; for "apocalyptic" designation, see Gozzoli 2006, p. 283.

Simpson 1972 年,第 6-7 页;Parkinson 2002 年,第 110、193 页;关于 "世界末日 "的称谓,见 Gozzoli 2006 年,第 283 页。 - ^ Morenz 2003, p. 103.

Morenz 2003 年,第 103 页。 - ^ Simpson 1972, pp. 6–7.

Simpson 1972 年,第 6-7 页。 - ^ Parkinson 2002, pp. 232–233.

Parkinson 2002 年,第 232-233 页。 - ^ Gozzoli 2006, pp. 283–304; see also Parkinson 2002, p. 233, who alludes to this genre being revived in periods after the Middle Kingdom and cites Depauw (1997: 97–9), Frankfurter (1998: 241–8), and Bresciani (1999).

Gozzoli 2006 年,第 283-304 页;另见 Parkinson 2002 年,第 233 页,他提到这种体裁在中王国之后的时期得到复兴,并引用了 Depauw(1997: 97-9)、Frankfurter(1998: 241-8)和 Bresciani(1999)的话。 - ^ Simpson 1972, pp. 7–8; Parkinson 2002, pp. 110–111.

Simpson 1972 年,第 7-8 页;Parkinson 2002 年,第 110-111 页。 - ^ Parkinson 2002, pp. 45–46, 49–50, 303–304.

Parkinson 2002 年,第 45-46 页、第 49-50 页、第 303-304 页。 - ^ Simpson 1972, p. 234.

Simpson 1972 年,第 234 页。 - ^ Parkinson 2002, pp. 197–198, 303–304; Simpson 1972, p. 234; Erman 2005, p. 110.

Parkinson 2002 年,第 197-198 页,第 303-304 页;Simpson 1972 年,第 234 页;Erman 2005 年,第 110 页。 - ^ Gozzoli 2006, pp. 301–302.

Gozzoli 2006 年,第 301-302 页。 - ^ Parkinson 2002, pp. 308–309; Simpson 1972, pp. 201, 210.

- ^ Parkinson 2002, pp. 111, 308–309.

Parkinson 2002 年,第 111、308-309 页。 - ^ Parkinson 2002, p. 308; Simpson 1972, p. 210; Erman 2005, pp. 92–93.

Parkinson 2002 年,第 308 页;Simpson 1972 年,第 210 页;Erman 2005 年,第 92-93 页。 - ^ Parkinson 2002, p. 309; Simpson 1972, p. 201; Erman 2005, p. 86.

Parkinson 2002 年,第 309 页;Simpson 1972 年,第 201 页;Erman 2005 年,第 86 页。 - ^ Bard & Shubert 1999, p. 674.

Bard & Shubert 1999 年,第 674 页。 - ^ Jump up to: a b c Forman & Quirke 1996, pp. 48–51; Simpson 1972, pp. 4–5, 269; Erman 2005, pp. 1–2.

Forman & Quirke 1996 年,第 48-51 页;Simpson 1972 年,第 4-5 页,第 269 页;Erman 2005 年,第 1-2 页。 - ^ Forman & Quirke 1996, pp. 116–117.

Forman & Quirke 1996 年,第 116-117 页。 - ^ Forman & Quirke 1996, pp. 65–109.

Forman & Quirke 1996 年,第 65-109 页。 - ^ Forman & Quirke 1996, pp. 109–165.

Forman & Quirke 1996 年,第 109-165 页。 - ^ Simpson 1972, p. 285.

Simpson 1972 年,第 285 页。 - ^ Erman 2005, p. 140.

Erman 2005 年,第 140 页。 - ^ Erman 2005, pp. 254–274.

Erman 2005 年,第 254-274 页。 - ^ Erman 2005, pp. 137–146, 281–305.

Erman 2005 年,第 137-146 页,第 281-305 页。 - ^ Erman 2005, p. 10.

Erman 2005 年,第 10 页。 - ^ Jump up to: a b Simpson 1972, p. 279; Erman 2005, p. 134.

Simpson 1972 年,第 279 页;Erman 2005 年,第 134 页。 - ^ Erman 2005, p. 134.

Erman 2005 年,第 134 页。 - ^ Simpson 1972, p. 297; Erman 2005, pp. 132–133.

Simpson 1972 年,第 297 页;Erman 2005 年,第 132-133 页。 - ^ Erman 2005, pp. 288–289; Foster 2001, p. 1.

Erman 2005 年,第 288-289 页;Foster 2001 年,第 1 页。 - ^ Simpson 1972, p. 289.

Simpson 1972 年,第 289 页。 - ^ Tait 2003, p. 10.

Tait 2003 年,第 10 页。 - ^ Lichtheim 1980, p. 104.