Why So Many Kids Still Die in Hot Cars Every Year

为什么每年仍有这么多孩子死于热车

Author: Andrea Thompson 安德里亚·汤普森

Length: • 9 mins

• 9 分钟

Annotated by howie.serious

由 howie.serious 注释

Cases of deadly heatstroke of children in cars have remained stubbornly persistent—here’s why they happen and how we can prevent them

车内儿童致命中暑案件持续存在——这是为什么以及我们如何预防

If you’ve ever driven a car, you’ve probably had the experience of parking on a hot, sunny day, running a quick errand or two and then returning to find your vehicle has become a stifling oven. That heat isn’t just uncomfortable; it can be deadly.

如果你曾经开过车,你可能有过在炎热的晴天停车,跑个小差事,然后回来发现你的车已经变成了一个闷热的烤箱的经历。那种热不仅让人不舒服,还可能致命。

Since the late 1990s the U.S. has seen an average of 37 children die each year from heatstroke after being unattended in a car or other vehicle—a grim statistic that has remained stubbornly steady despite decades of efforts to raise awareness. The problem, experts say, stems from a lack of understanding of just how quickly a car can heat up and overwhelm a person and the difficulty of comprehending that even the most loving caregiver might be capable of leaving a child in a vehicle. Because news coverage tends to focus on more sensational stories that involve neglect, “the public perception is ‘that’s a bad parent; I’m not a bad parent,’” says Andrew Grundstein, who studies climate and health at the University of Georgia.

自 20 世纪 90 年代后期以来,美国平均每年有 37 名儿童因无人看管在车内或其他车辆中中暑死亡——这一严峻的统计数据尽管经过数十年的努力提高意识,仍然顽固地保持稳定。专家表示,问题在于缺乏对汽车能多快升温并压倒一个人的理解,以及难以理解即使是最有爱心的看护者也可能会把孩子留在车里的事实。由于新闻报道往往集中在涉及疏忽的更耸人听闻的故事上,“公众的看法是‘那是个坏父母;我不是坏父母,’”研究气候和健康的乔治亚大学的安德鲁·格伦斯坦说。

Scientific American dug into the science of why cars get so hot, why faults in our memory can lead anyone to forget even something as important as a child being in the back seat and what strategies can avert these deaths. “They’re so preventable,” Grundstein says. “They don’t have to happen.”

Scientific American深入研究了为什么汽车会变得如此炎热,为什么记忆中的错误会导致任何人忘记甚至像孩子在后座这样重要的事情,以及哪些策略可以避免这些死亡。“它们是如此可预防,”格伦斯坦说。“它们不必发生。”

A ‘National Problem’ 一个‘全国性问题’

Perhaps no one knows as much about the issue of pediatric vehicular heatstroke as Jan Null, an adjunct professor at San Jose State University, who maintains the most robust U.S. dataset on such deaths at NoHeatStroke.org. He pulls the numbers primarily from news reports because there is no official centralized, comprehensive record; coroners don’t always note that such deaths occurred in a car or involved heat.

也许没有人比圣何塞州立大学的兼职教授 Jan Null 更了解儿童车内中暑的问题,他在NoHeatStroke.org上维护着美国最全面的此类死亡数据集。他主要从新闻报道中获取数据,因为没有官方的集中、全面记录;验尸官并不总是注明这些死亡是发生在车内或与热有关。

Null fell into what he calls his “sad niche” when he received a call from a reporter in July 2001 after a boy in the San Francisco area had died in a hot car. The reporter wanted an expert’s take on what temperatures might have been involved. Null couldn’t find any good studies on that question and quickly realized that little solid information was available. So he took it upon himself to start investigating and gathering data.

Null 在 2001 年 7 月接到一名记者的电话后,进入了他所谓的“悲伤领域”,当时旧金山地区一名男孩在一辆热车中死亡。记者想要一个专家对可能涉及的温度的看法。Null 找不到任何关于这个问题的好研究,并很快意识到几乎没有可靠的信息可用。因此,他决定自己开始调查和收集数据。

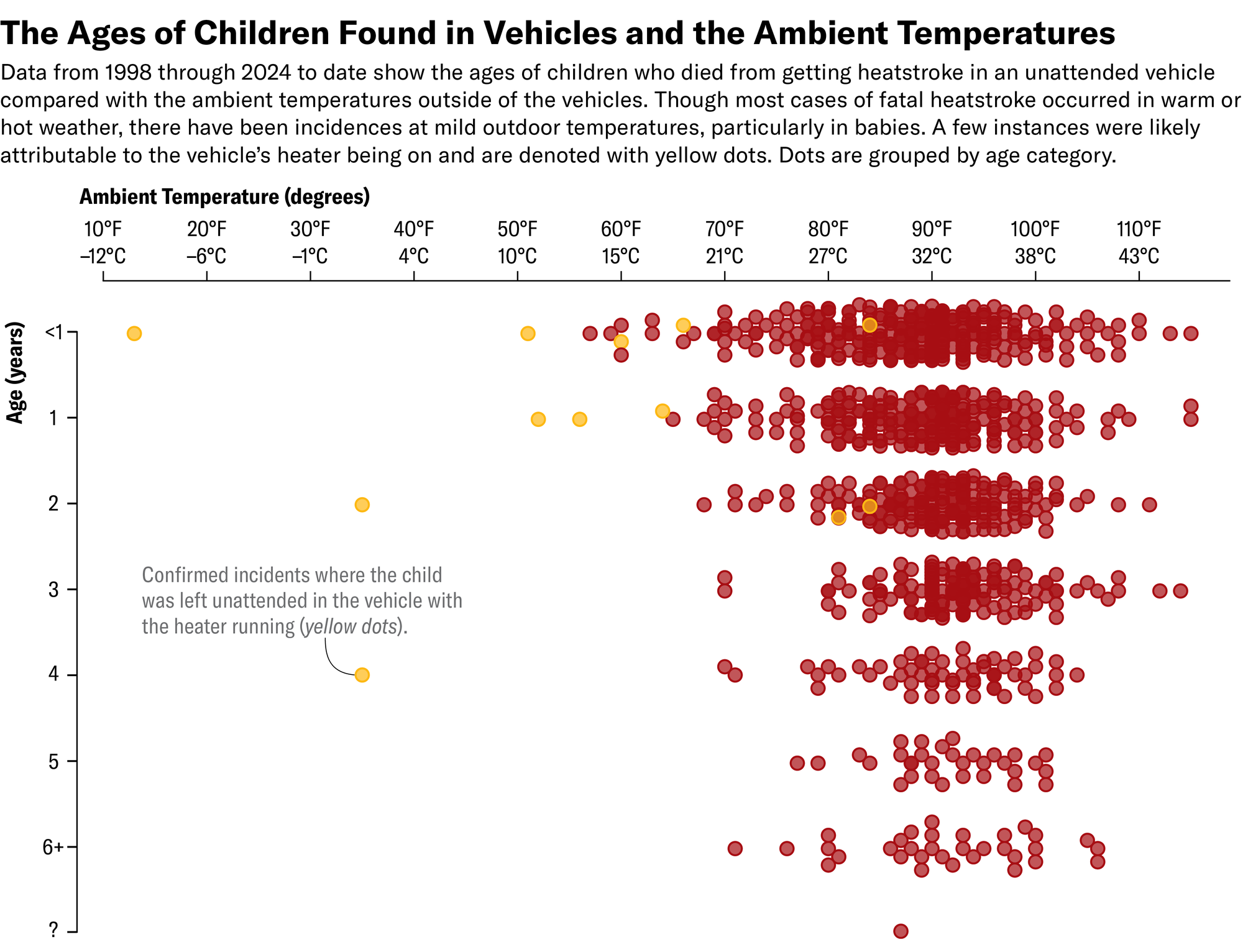

More than 20 years later Null continuously updates his database, which includes the age and gender of each child, where the death occurred and other pertinent information. The vast majority of deaths involve very young children: about 88 percent are three years old or younger, and nearly one third are less than a year old.

二十多年后,Null 不断更新他的数据库,其中包括每个孩子的年龄和性别、死亡发生的地点以及其他相关信息。绝大多数死亡涉及非常年幼的孩子:大约 88%的孩子年龄在三岁或以下,近三分之一的孩子不到一岁。

Zane Wolf; Source: NoHeatstroke.org

Zane Wolf; 来源:NoHeatstroke.org

Such heat-related fatalities have happened in every month of the year, though they tend to peak in summer. They happen more often across the southern portion of the country because of the longer hot season and more intense heat. But they have happened almost everywhere—only two states, Alaska and New Hampshire, has not had a recorded death of a child in a hot car between 1998 and the present (and New Hampshire had one in 1997). “There’s really not a safe place for this. It’s really a national problem,” says Grundstein, who has worked with Null. He also notes that the problem goes far beyond the U.S., citing studies in Europe and South America as well.

这种与热相关的死亡在一年中的每个月都有发生,尽管它们往往在夏季达到高峰。由于炎热季节更长和高温更强,它们在全国南部地区发生得更频繁。但几乎在任何地方都发生过——自 1998 年以来,只有两个州,阿拉斯加和新罕布什尔州,没有记录到孩子在热车中死亡的事件(而新罕布什尔州在 1997 年有过一次)。“真的没有一个安全的地方。这确实是一个全国性的问题,”与 Null 合作的 Grundstein 说。他还指出,这个问题远远超出了美国,引用了欧洲和南美的研究。

How Hot Can It Get in a Car?

车内温度能有多高?

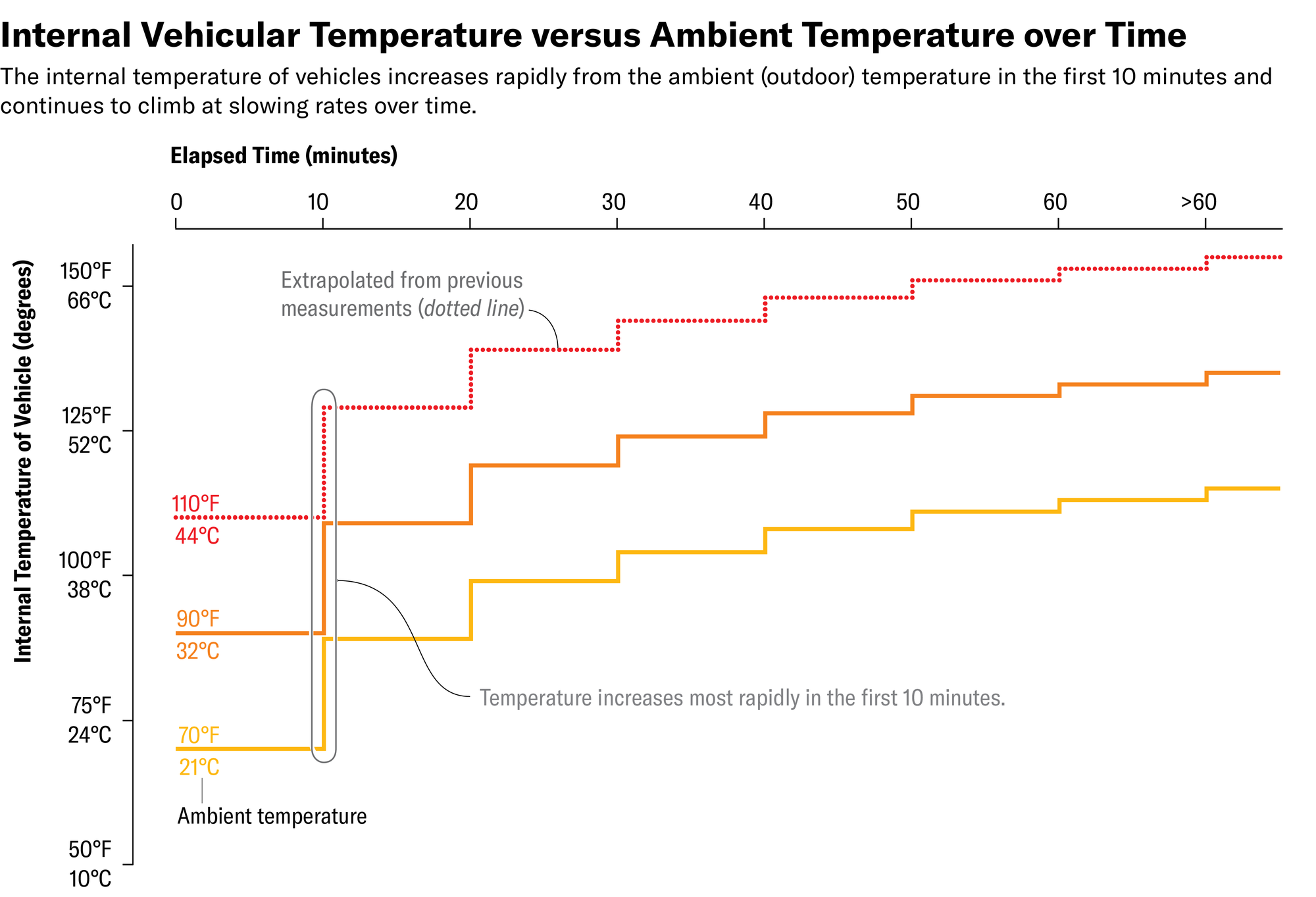

Until Null started his work, there were no comprehensive measures of how hot a car’s interior could get in different outside temperatures or of how quickly this heat could become dangerous. In preliminary anecdotal work Null did in his own car, and later in controlled studies, he found “very rapid rates of rise”—around 19 degrees Fahrenheit (10.6 degrees Celsius) in the first 10 minutes—regardless of the starting outdoor temperature or type of vehicle.

在 Null 开始他的工作之前,没有全面的措施来衡量在不同的外部温度下车内温度能达到多高,或者这种热量多快会变得危险。在 Null 在自己的车内进行的初步轶事工作中,以及后来在控制研究中,他发现“温度上升速度非常快”——在前 10 分钟内大约上升 19 华氏度(10.6 摄氏度)——无论起始的室外温度或车辆类型如何。

The inside temperature continues to rise at a slowing rate, reaching extremely high temperatures. If the outside air is 90 degrees F (32 degrees C), the temperature in a car will reach 133 degrees F (56 degrees C) in roughly an hour. Even with a mild outdoor temperature of 70 degrees F (21 degrees C), a car’s interior can reach 113 degrees F (45 degrees C) in that time.

车内温度继续以减缓的速度上升,达到极高的温度。如果外部空气温度为 90 华氏度(32 摄氏度),车内温度将在大约一小时内达到 133 华氏度(56 摄氏度)。即使外部温度为 70 华氏度(21 摄氏度),车内温度在那段时间内也能达到 113 华氏度(45 摄氏度)。

Zane Wolf; Source: NoHeatstroke.org

Zane Wolf; 来源:NoHeatstroke.org

That’s because “cars operate like a greenhouse,” Grundstein says. The relatively short wavelengths of sunlight are able to stream through the windows of the car, heating up the air and surfaces inside. Those surfaces then radiate longer wavelengths of infrared energy—or heat—that do not penetrate back out of the windows but very efficiently heat up the inside air.

这是因为“汽车像温室一样运作,”Grundstein 说。相对较短波长的阳光能够穿过车窗,照射到车内的空气和表面。这些表面然后辐射出较长波长的红外能量——或热量——这些热量无法穿透车窗回到外面,但非常有效地加热了车内空气。

Why Children Are So Susceptible to Hot Cars

为什么孩子们对热车如此敏感

Such heat is dangerous for any person in a car, but children, particularly very young ones, are so susceptible in part because “they’re strapped into a car seat; they’re not able to remove clothing; they’re not able to get out of the car,” Grundstein says. “They’re literally trapped in there.”

这种热量对车内的任何人都是危险的,但孩子们,尤其是非常小的孩子,特别容易受到影响,部分原因是“他们被绑在安全座椅上;他们无法脱掉衣服;他们无法下车,”格伦斯坦说。“他们实际上被困在里面。”

The longer the child is in the car, the more the heat radiating from its surfaces is driving up the child’s core body temperature. “The human body is just gaining heat internally” in this situation, says Susan Yeargin, who studies heat illness at the University of South Carolina.

孩子在车里的时间越长,车内表面散发的热量就越多,孩子的核心体温就会上升。“在这种情况下,人体内部的热量只会增加,”研究热病的南卡罗来纳大学的苏珊·耶尔金说。

A normal human body temperature is around 98 degrees F (36.6 degrees C). It becomes dangerous when the core temperature rises to around 104 to 105 degrees F (about 40 degrees C). Potentially fatal heatstroke—often marked by hot, dry skin, dizziness and vomiting—typically occurs around 107 to 108 degrees F (about 42 degrees C), Yeargin says.

正常人体温度约为 98 华氏度(36.6 摄氏度)。当核心温度升至约 104 至 105 华氏度(约 40 摄氏度)时,就会变得危险。潜在致命的中暑——通常表现为皮肤灼热、干燥、头晕和呕吐——通常发生在 107 至 108 华氏度(约 42 摄氏度)左右,耶尔金说。

Children primarily lose heat by simply radiating it from their skin to the air. Perspiration—the main way adults cool themselves—doesn’t take over as the body’s primary cooling method until puberty, so younger children cannot sweat away heat as well as adults do. But in a hot car, “the heat gain in the environment is just so much that the child or the person can’t dissipate it with the sweating mechanism alone,” Yeargin says. Eventually the body is only gaining heat, and that heat can quickly damage internal organs.

孩子们主要通过将热量从皮肤辐射到空气中来散热。出汗——成年人主要的降温方式——直到青春期才成为身体的主要降温方式,所以年幼的孩子不能像成年人那样通过出汗来散热。但在热车中,“环境中的热量增加如此之大,以至于孩子或人无法仅通过出汗机制来散热,”耶尔金说。最终,身体只会增加热量,而这种热量会迅速损害内部器官。

Why Parents Can Forget Their Children in a Car

为什么父母会忘记把孩子留在车里

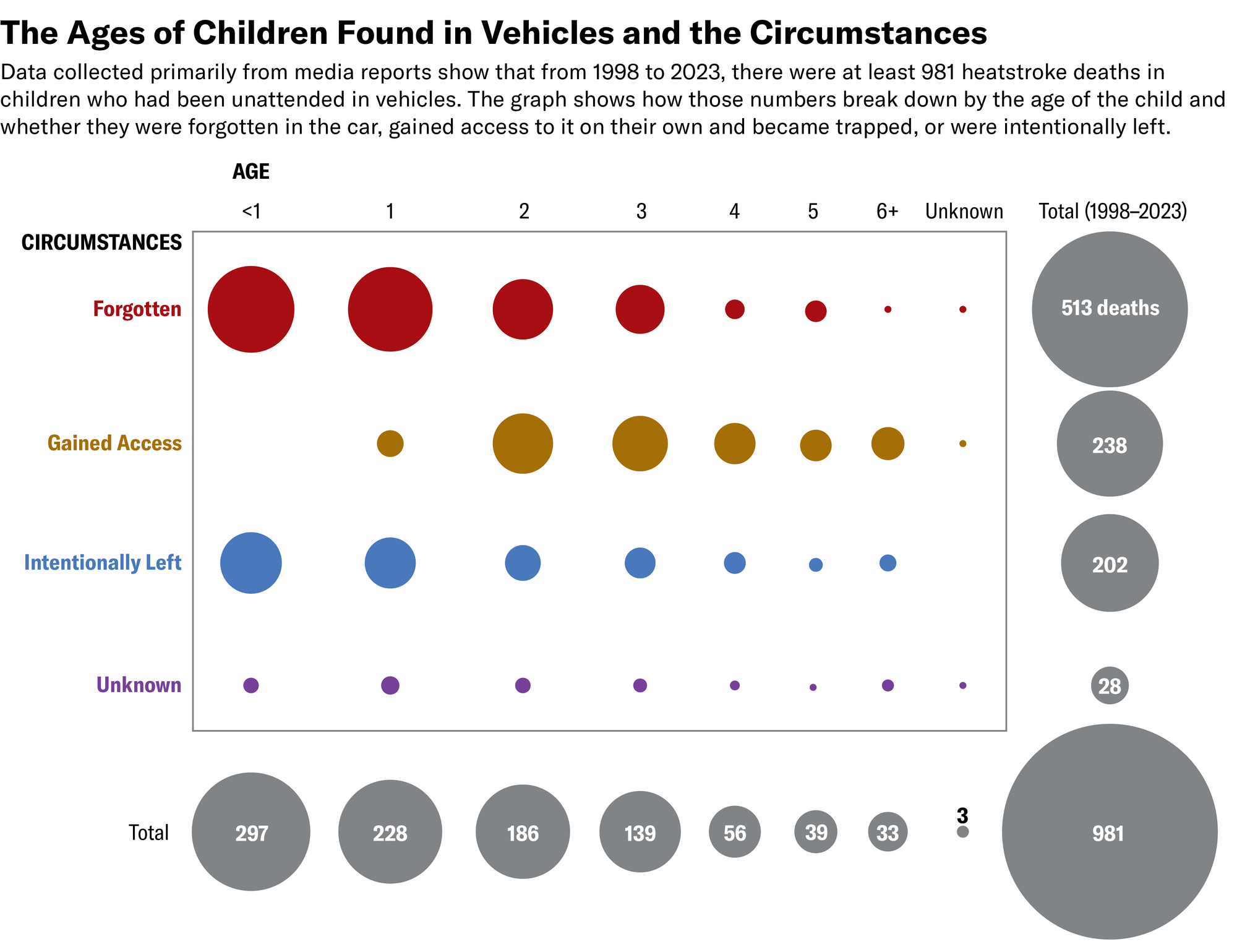

The cases of children who die from heatstroke in a vehicle fall primarily into three categories: about 20 percent are knowingly left; one quarter gain access to a car and become trapped; and more than half are forgotten. Of the latter, half are left in cars because someone forgot to drop them off for childcare—typically a parent or other caregiver who does not usually drive the child there. “No one thinks they’re ever going to do that,” Grundstein says, “but it happens to anyone.”

孩子因中暑死于车内的案例主要分为三类:约 20%是被故意留下的;四分之一是自己进入车内并被困住的;超过一半是被遗忘的。在后一类中,一半是因为有人忘记送他们去托儿所——通常是那些平时不负责开车送孩子的父母或其他看护人。格伦斯坦说:“没有人认为他们会这样做,但这会发生在任何人身上。”

One reason it can happen to an otherwise attentive caregiver is that “as magnificent as our brain is, our brain is flawed,” says David Diamond, a neuroscientist at the University of South Florida, who has studied this issue for more than 20 years. Our brain, he explains, has two independent memory systems: One is our conscious memory, handled by the hippocampus. “This is where we actually keep things on our mind,” Diamond explains. The other is a “very primitive but powerful brain memory system” controlled by the basal ganglia, where actions we take repeatedly—brushing teeth, locking a door—get ingrained as habit. That latter memory system dominates when we’re driving, Diamond says.

这可能发生在一个平时很细心的看护人身上的一个原因是,“尽管我们的大脑非常了不起,但它也是有缺陷的,”南佛罗里达大学的神经科学家大卫·戴蒙德说,他研究这个问题已有 20 多年。他解释说,我们的大脑有两个独立的记忆系统:一个是由海马体处理的有意识记忆。“这是我们真正记住事情的地方,”戴蒙德解释道。另一个是由基底神经节控制的“非常原始但强大的大脑记忆系统”,我们反复进行的动作——刷牙、锁门——会作为习惯被铭记。戴蒙德说,当我们开车时,后者的记忆系统占主导地位。

“No one thinks they’re ever going to do that, but it happens to anyone.” —Andrew Grundstein, University of Georgia

“没有人认为他们会这样做,但这会发生在任何人身上。” —安德鲁·格伦斯坦,乔治亚大学

He offers a typical example: Your significant other asks you to drop by a store to pick up milk on the way home from work, a stop you don’t normally make. You agree, think about how you need to alter your route and set off. But as you start off on a route you’ve driven hundreds of times before, the basal ganglia makes you “go into autopilot mode,” Diamond says, “and you drive right past the store.”

他举了一个典型的例子:你的另一半让你下班回家时顺便去商店买牛奶,这是你平时不会去的地方。你同意了,想着需要改变路线并出发。但当你开始走一条你已经开了数百次的路线时,基底神经节让你“进入自动驾驶模式,”戴蒙德说,“然后你就直接开过了商店。”

A similar thing can happen when a caregiver is driving a child to day care on their way to work, particularly if they are not the one who normally drops off the child. Their brain goes on autopilot, and they end up driving their normal route to their job or train station or wherever their end destination is. “The habit takes over and keeps them on their routine,” Diamond says. And if the child is out of view or asleep, the parent may not notice them. “No matter how precious the memory is,” it can fall through the cracks, he says. “It’s easy to judge; it’s difficult to understand,” Diamond adds. “It’s part of being human.”

类似的事情可能会发生在看护者在上班途中开车送孩子去日托时,特别是如果他们不是通常送孩子的人。他们的大脑进入自动驾驶模式,最终沿着他们正常的路线开车去上班地点或火车站或其他目的地。“习惯接管并让他们保持日常惯例,”戴蒙德说。如果孩子不在视线范围内或在睡觉,父母可能不会注意到他们。“无论记忆多么珍贵,”它都可能被忽略,他说。“评判很容易;理解很难,”戴蒙德补充道。“这是人类的一部分。”

Then “what the brain seems to do is it leaves a false memory” that the child is at day care or wherever the caregiver planned to bring them, Diamond says. “[The caregiver has] absolute certainty that the child is wherever the child belongs”—even thinking at the end of the day, “Oh, I need to go to day care to pick up my child.”

然后“似乎大脑会留下一个false memory”即孩子在日托或看护者计划带他们去的地方,戴蒙德说。“[看护者]绝对确信孩子在该在的地方”——甚至在一天结束时想着,“哦,我需要去日托接我的孩子。”

How Do We Prevent Heatstroke in Cars?

如何防止汽车中暑?

There are ways to help prevent children from being forgotten or otherwise becoming trapped in cars. But because it happens for a variety of reasons, “you need different strategies for different circumstances,” Grundstein says.

有一些方法可以帮助防止孩子被遗忘或被困在车里。但由于发生的原因多种多样,“你需要针对不同情况采取不同的策略,”格伦斯坦说。

Cars should always be kept locked so that a child cannot open a door, climb in and subsequently become stuck because of child safety locks or other reasons, experts say. Children should be taught that a car is not a safe place to play. And if a child has gone missing, the first place to check is a pool, if one is nearby, and then the car, Null says, because they are the two places a child can most quickly come to harm.

专家表示,汽车应始终保持锁闭状态,以防孩子打开车门、爬进去并因儿童安全锁或其他原因被困。应教导孩子汽车不是一个安全的玩耍场所。如果孩子失踪,首先要检查的是游泳池,如果附近有的话,然后是汽车,纳尔说,因为这是孩子最容易受到伤害的两个地方。

Zane Wolf; Source: NoHeatstroke.org

Zane Wolf; 来源: NoHeatstroke.org

When it comes to children intentionally left in a car—often with no harmful intent—awareness campaigns can help. Twenty-one states have also passed laws making it illegal to leave a child in a car, though many have exceptions, and it is unclear whether those have had any effect on the number of cases. Twenty-four states have “Good Samaritan” laws that protect anyone who sees a child in a car and takes action to help them, such as breaking a window. Null says if you see a child alone in a car, your first action should be to call 911, particularly if there is any sign of distress.

当涉及到故意将孩子留在车里时——通常没有恶意——宣传活动可以有所帮助。二十一州还通过了法律,规定将孩子留在车里是非法的,尽管许多法律有例外情况,并且不清楚这些法律是否对案件数量产生了影响。二十四个州有“好撒玛利亚人”法律,保护任何看到孩子在车里并采取行动帮助他们的人,例如打破车窗。Null 说,如果你看到一个孩子独自留在车里,你的第一个行动应该是拨打 911,特别是如果有任何痛苦的迹象。

To help prevent children from being forgotten, new car models are now required to include technology that will remind the driver to check the back seat. But it will take some time for this technology to spread through the U.S. car fleet.

为了帮助防止孩子被遗忘,新车型号现在需要包括提醒司机检查后座的技术。但这种技术在美国车队中普及需要一些时间。

In the meantime—given that 25 percent of cases of a child dying in a hot car occur when they are forgotten on the way to a childcare provider—Null would like to see childcare provider contracts include a provision that the provider must call the parent if the child has not arrived by a certain time. Because drop-off usually occurs earlier in the morning, Null says, “it’s gotten warm, but it’s not gotten that hot early in the day.” So the chances are greater that the child can be rescued before they come to serious harm.

与此同时——鉴于 25%的孩子在去托儿所的路上被遗忘而死于热车的案例——Null 希望托儿所合同中包括一项规定,即如果孩子在某个时间之前没有到达,托儿所必须打电话给家长。因为通常在早上较早的时候进行放学,Null 说,“天气已经变暖,但一天早上还没有那么热。”所以孩子在遭受严重伤害之前被救出的机会更大。

There are also “look before you lock” campaigns, many of which include low-tech suggestions for reminding a caregiver that their child is in the back seat. This could include putting a Post-it note on the steering wheel or keeping a work bag or purse in the back seat. Diamond particularly likes the method of keeping a stuffed animal or some other object in the car seat when it’s not in use and then routinely moving that object to the front passenger seat or, if small enough, attaching it to the steering wheel when the child is put into the car seat. But “you have to do it every time you have your child” for the reminder to work, Diamond says.

还有“锁前看一看”运动,其中许多包括一些低技术含量的建议,以提醒看护人他们的孩子在后座。这可能包括在方向盘上贴一张便条,或者将工作包或钱包放在后座。Diamond 特别喜欢在安全座椅未使用时将一个毛绒玩具或其他物品放在车座上,然后在孩子放入安全座椅时将该物品常规地移到前排乘客座位上,或者如果足够小,将其附在方向盘上。但 Diamond 说,“每次带孩子时都必须这样做”才能起到提醒作用。

The thorniest problem with those approaches is that they require people to confront and accept the thought that they could forget their child. “Probably the biggest roadblock is that people say, ‘It would never happen to me,’” Null says.

这些方法中最棘手的问题是它们要求人们面对并接受他们可能会忘记孩子的想法。“可能最大的障碍是人们说,‘这绝不会发生在我身上,’”Null 说。

Because of that and the fact that “people are fallible,” he doesn’t think such deaths will ever reach zero. But he and others do think we can bring the numbers down. “Awareness and education are huge,” he says, adding that he personally will keep tracking the data and providing his database for free in order to advocate for safety. “I would love to get a different passion project,” he says. In the meantime, he’ll “keep slugging away.”

因为这个原因以及“人是会犯错的”这个事实,他认为这种死亡事件永远不会达到零。但他和其他人确实认为我们可以减少这些数字。“意识和教育是巨大的,”他说,并补充说他个人将继续跟踪数据并免费提供他的数据库以倡导安全。“我希望能有一个不同的激情项目,”他说。同时,他将“继续努力。”

Editor’s Note (9/26/24): This article was edited after posting to correct Jan Null’s current position at San Jose State University and the context of the call he received in July 2001.

编辑注(2024 年 9 月 26 日):本文在发布后进行了编辑,以更正 Jan Null 在圣何塞州立大学的现任职位以及他在 2001 年 7 月接到的电话的背景。