Intrinsic Motivation: A deep dive

内在动机:深入探讨

I dig into the reseach on intrinsic motivation. Super interesting subject. Long but hopefully quite thorough.

我深入研究了内在动机的相关内容。非常有趣的主题。篇幅较长,但希望内容足够详尽。

Soon after I entered into year 12, something crazy happened:

进入 12 年级后不久,发生了一件疯狂的事情:

I started studying.

我开始学习了。

Like – a lot.

非常喜欢。

Between the ages of 12 and 16, I’d had no motivation for school whatsoever. I didn’t do my homework. I didn’t revise for my exams. I diligently ignored everything my teachers said to me.

在 12 到 16 岁之间,我对学校完全没有动力。我不做作业,也不为考试复习。我刻意无视老师对我说的每一句话。

While I was doing my GCSEs, my parents would force me to sit in my room with no distractions and study for two hours each day. Rather than put this time to good use, I would simply sit at my desk, stare out the window, and run down the clock.

在我准备 GCSE 考试的时候,我的父母会强迫我每天在房间里不受任何干扰地学习两个小时。然而,我并没有好好利用这段时间,而是坐在书桌前,盯着窗外发呆,直到时间耗尽。

But then suddenly, almost overnight, something changed:

但突然间,几乎在一夜之间,事情发生了变化:

I started to care about doing well. I started to find my subjects interesting. I started to like – and listen to – my teachers. I developed absolute tunnel vision for my studies, and I eventually managed some of the best A Level grades in my entire school.

我开始在意自己的表现。我开始觉得我的学科很有趣。我开始喜欢——并且倾听——我的老师们。我对学习产生了绝对的专注,最终我在整个学校取得了最好的 A Level 成绩。

From the outside, it looked like I had suddenly decided to knuckle down and start taking my studies seriously – but from the inside, this isn’t what happened at all.

从表面上看,我似乎突然决定要认真学习,开始重视我的学业——但从内心来看,事情完全不是这样。

There was no knuckling down going on; I wasn’t working hard in any real sense. I would often put in twelve hours of studying each day and at no point did I feel tired or strained or stressed. I felt curious, energised – excited.

没有任何埋头苦干的感觉;我并没有真正意义上地努力工作。我常常每天学习十二个小时,但从没感到疲倦、紧张或压力。我感到好奇,充满活力——兴奋。

This kind of experience – this sudden turning on (and off) – of motivation has happened to me a number of times throughout my life.

这种经历——这种动机的突然开启(和关闭)——在我的一生中发生过多次。

Sometimes – for reasons that I’ve been trying to understand – I’m able to work happily and without rest for many weeks or months at a time. But at others, it’s as if the supply of motivation has run dry and getting anything done feels next to impossible.

有时候——出于一些我一直试图理解的原因——我能够连续几周或几个月愉快地工作而不休息。但在其他时候,动力仿佛枯竭了一般,完成任何事情都感觉几乎不可能。

I don’t think I’m alone in this.

我想我不是唯一有这种感觉的人。

In fact, to some extent or another, I think the above description probably applies to everyone.

事实上,在某种程度上,我认为上面的描述可能适用于每个人。

I also don’t think many of us have a good idea as to what’s going on here.

我也认为我们中很多人都不清楚这里到底发生了什么。

This post is my attempt to find out.

这篇文章是我试图找出答案的尝试。

This is a topic I’ve been researching in and around for quite a while, and as far as I can see, all roads lead to the idea of Intrinsic Motivation.

这是我研究了相当一段时间的话题,就我所见,所有路径都指向内在动机的理念。

Playing sport. Writing. Painting. Travelling. Exploring. Hiking. Reading.

运动。写作。绘画。旅行。探索。徒步。阅读。

For the most part, we engage in these activities for their own sake – because they are inherently enjoyable.

在大多数情况下,我们参与这些活动是为了活动本身——因为它们本身就令人愉快。

When we do something for its own sake – without regard for rewards, punishments, or really outcomes of any kind – we can be said to be intrinsically motivated. In contrast, when we’re motivated by external pressures and outcomes, we can can be said to be extrinsically motivated.

当我们为了某件事本身而去做——不考虑奖励、惩罚,或者任何形式的结果——我们可以说这是内在动机。相反,当我们受到外部压力和结果的驱动时,我们可以说这是外在动机。

There’s good evidence to suggest that the more intrinsically motivated we are to do a task, the more we enjoy it, the better we learn, the better we perform, and the more likely we are to persevere in the face of obstacles and setbacks.

有充分的证据表明,我们对某项任务的内在动机越强,我们就越享受它,学习效果越好,表现越出色,也越有可能在面对障碍和挫折时坚持下去。

The hypothesis that I’ll be pushing throughout this piece is that whenever I’ve found myself in one of these high-motivation life periods, I’ve unwittingly stumbled upon a rich vein of intrinsic motivation. It therefore stands to reason that if I want to understand these experiences – and how to create more of them – I need to understand intrinsic motivation.

我在这篇文章中将始终推崇的假设是,每当我发现自己处于这些高动力的人生阶段时,我都无意中发现了内在动力的丰富源泉。因此,如果我想理解这些经历——以及如何创造更多这样的经历——我就需要理解内在动力。

As it turns out, intrinsic motivation looks to be an extremely delicate thing. Under the right conditions, it can be encouraged and drawn out of us; in the wrong conditions, it can be suffocated, stifled – maybe even killed.

事实证明,内在动机似乎是一种极其微妙的东西。在适当的条件下,它可以被鼓励和激发出来;而在错误的条件下,它可能会被压制、扼杀——甚至可能被彻底摧毁。

Thankfully, there’s been an absolute mountain of research done in this area – mostly carried out under the rubric of Self-Determination Theory – and in this piece, I’m going to do a deep-dive on it all.

值得庆幸的是,在这个领域已经进行了大量的研究——大多是在自我决定理论的框架下进行的——在这篇文章中,我将对这一切进行深入探讨。

Here goes. 开始了。

Main topics to be covered:

主要涵盖的主题:

What is intrinsic motivation? A quick history + some context

什么是内在动机?一个简短的历史 + 一些背景How do psychologists measure intrinsic motivation?

心理学家如何测量内在动机?Discussion - concerns, criticisms, and miscellaneous ideas:

讨论 - 关注点、批评和各种想法:

1. What is intrinsic motivation? A quick history + some context

1. 什么是内在动机?简短的历史 + 一些背景

The general concept of intrinsic motivation is quite intuitive, so I’m hoping the sketch I’ve offered up so far will be enough to give you the general gist.

内在动机的基本概念非常直观,所以我希望我目前提供的草图足以让你了解大致情况。

Saying that, there are a number of possible points of confusion here, so it’s worth spending a little bit of time fleshing out this definition and distinguishing intrinsic motivation from other closely related concepts.

话虽如此,这里有几个可能的混淆点,因此值得花一点时间来详细说明这个定义,并将内在动机与其他密切相关的概念区分开来。

To do this, a whistle-stop tour through the history and wider research context of the concept is going to be useful (and hopefully interesting, too!):

为了做到这一点,快速回顾一下这个概念的历史和更广泛的研究背景将会很有用(也希望能有趣!):

When the research on intrinsic motivation first started, behaviourism was still the dominant school of thought within psychology. Operant Psychology – B. F. Skinner’s development on the original behaviourist position – was primarily concerned with how reinforcement and reinforcement contingencies influence the frequency of different behaviours.

当内在动机的研究最初开始时,行为主义仍然是心理学中的主导思想流派。操作心理学——B. F. Skinner 在原始行为主义立场上的发展——主要关注强化和强化条件如何影响不同行为的频率。

The upshot (with many qualifications) was that the more you reward a behaviour, the more frequently that behaviour will occur, e.g. give a mouse some cocaine for pulling a lever and over time the mouse will learn to start pulling that lever like it’s life depends on it.

结果(有许多限定条件)是,你越奖励某种行为,这种行为就会越频繁地发生,例如,给一只老鼠一些可卡因作为拉动杠杆的奖励,随着时间推移,老鼠会学会像性命攸关一样开始拉动那个杠杆。

Particularly relevant to our discussion here is the fact that there is no space in this theory for intrinsic motivation. Before receiving reinforcement, behaviour is more or less random (e.g. maybe the mouse moves around randomly and knocks the lever, resulting in cocaine being administered). Once reinforcement has been dished out, motivation is then present to the extent that the behaviour has been reinforced.

特别与我们这里的讨论相关的是,这个理论中没有内在动机的空间。在获得强化之前,行为或多或少是随机的(例如,老鼠可能随机移动并撞到杠杆,导致可卡因被施用)。一旦强化被给予,动机就会出现,其程度取决于行为被强化的程度。

That’s pretty much it.

差不多就是这样。

Credit where it’s due: behaviourism and operant psychology were able to shed light on many previously enshadowed phenomena – but over time, a number of experimental findings began to emerge that put this paradigm under increasing pressure.

功劳归功于应得之处:行为主义和操作心理学能够阐明许多先前被遮蔽的现象——但随着时间的推移,一些实验发现开始出现,对这一范式施加了越来越大的压力。

Here are a couple of them:

这里有其中的几个:

Nissen (1930) found that rats would cross an electrified grid in order to get to a novel maze area on the other side. Because neither the grid nor the novel space had been paired with a reinforcer, operant psychology would predict that the electrified grid would act as a negative reinforcer, deterring the exploratory behaviour. This obviously isn’t what happened.

Nissen (1930) 发现,老鼠会穿越一个带电的网格,以到达另一侧的新奇迷宫区域。因为网格和新奇空间都没有与强化物配对,操作心理学预测带电网格会作为负强化物,阻止探索行为。显然,事实并非如此。Butler (1957) found that rhesus monkeys would learn discrimination problems solely for the opportunity to visually explore the environment. Again, this exploratory behaviour had not been previously reinforced, so this left behaviourists their heads.

巴特勒(Butler,1957)发现,恒河猴会仅仅为了有机会视觉探索环境而学习辨别问题。这种探索行为之前并未得到强化,因此这让行为主义者感到困惑。Montgomery (1955) gave rats a chance to either return to their home base or explore a novel environment (that had never been reinforced in any way). The rats showed a strong preference for the latter.

蒙哥马利(1955)给老鼠一个机会,让它们要么返回自己的基地,要么探索一个全新的环境(这个环境从未以任何方式被强化过)。老鼠们明显更倾向于后者。Harlow (1953b) found that rhesus monkeys would solve discrimination tasks with the sole reward of being able to manipulate novel objects. Interestingly, these manipulation drives were extremely difficult to eradicate via the usual processes of extinction (e.g. if you stop rewarding the rat with cocaine when it pulls the lever, it will eventually stop pressing the lever. Not so with the drive to manipulate).

Harlow (1953b) 发现,恒河猴会解决辨别任务,唯一的奖励就是能够操作新奇的物体。有趣的是,这些操作驱动力通过通常的消退过程极难消除(例如,如果你停止在老鼠拉动杠杆时用可卡因奖励它,它最终会停止按压杠杆。但操作驱动力并非如此)。

The trend here, as I’m sure you’ve noticed, is that there are certain kinds of behaviours that we – or, at least, animals generally – are reliably motivated to perform but that have never been reinforced. A certain class of these behaviours seems to be tied to exploration, and this class of behaviour is often far more resistant to extinction than the kinds of behaviours that have been learned via reinforcement, e.g. the lever pressing of a coke addicted mouse.

这里的趋势,正如我相信你已经注意到的,是我们——或者至少是一般动物——总是被可靠地激励去执行某些行为,但这些行为从未被强化过。其中一类行为似乎与探索有关,这类行为往往比通过强化学习到的行为(例如,一只可卡因成瘾的老鼠按压杠杆的行为)更不容易消失。

After a decade or so of discussion, nobody was able to find a way of convincingly integrating these findings into the dominant paradigms of the day. This culminated in a 1959 paper by Robert White, where he proposed that these behaviours were best viewed as being fuelled by innate psychological tendencies – tendencies associated with interest, curiosity, exploration, and play.

经过大约十年的讨论,没有人能够找到一种令人信服的方式将这些发现融入当时的主流范式中。这最终体现在罗伯特·怀特 1959 年的一篇论文中,他提出这些行为最好被视为是由天生的心理倾向所驱动的——这些倾向与兴趣、好奇心、探索和游戏相关。

There’s a whole lot more to this story than is worth covering here, but the crux of this all is that White’s understanding of these behaviours ran in the face of the behaviourist theories of the day and ultimately paved the way for much of the research into intrinsic motivation that has happened since.

这个故事还有很多内容值得探讨,但这里不予赘述,核心在于 White 对这些行为的理解与当时的行為主义理论相悖,最终为后来关于内在动机的许多研究铺平了道路。

As it goes, almost all of the research into intrinsic motivation has been done under the rubric of Self-Determination Theory (SDT). Part of the reason for this is that SDT pretty much started out as THE study of intrinsic motivation (more on this shortly), before then expanding into a fully-fledged theory of human flourishing in its own right.

几乎所有的内在动机研究都是在自我决定理论(SDT)的框架下进行的。部分原因是 SDT 最初几乎就是内在动机研究的代名词(稍后会详细说明),随后才发展成为一个完整的、独立的关于人类幸福的理论。

For good measure, here’s a fleshed out definition of intrinsic motivation from the founders of SDT themselves:

为了更全面起见,这里是 SDT 创始人自己对内在动机的详细定义:

“[Intrinsic Motivation is] the primary and spontaneous propensity of some organisms, especially mammals, to develop through activity—to play, explore, and manipulate things and, in doing so, to expand their competencies and capacities. This natural inclination is an especially significant feature of human nature that affects people’s cognitive and emotional development, quality of performance, and psychological well-being. It is among the most important of the inner resources that evolution has provided (Deci & Ryan, 2000; Ryan & Hawley, 2016), and because it represents a prototypical manifestation of integrative organismic tendencies, SDT research began with it as a primary focus."

“[内在动机是]某些生物体,尤其是哺乳动物,通过活动发展自身的主要和自发的倾向——玩耍、探索和操控事物,并在此过程中扩展他们的能力和容量。这种自然倾向是人性中一个特别显著的特征,影响着人们的认知和情感发展、表现质量以及心理健康。它是进化所提供的最重要的内在资源之一(Deci & Ryan, 2000; Ryan & Hawley, 2016),并且因为它代表了整合性有机体倾向的典型表现,SDT 研究一开始就以此为主要焦点。”

So, in other words: intrinsic motivation isn’t really about engaging in purely pleasurable activities. For example, I don’t think that SDT would say that eating delicious cookies would be an example of an intrinsically motivated activity. Rather, SDT’s conception of intrinsic motivation is more about engaging in activities that allow us to explore, expand, and develop our capacities (and that also happen to be deeply enjoyable!).

因此,换句话说:内在动机并不是真的关于参与纯粹令人愉悦的活动。例如,我不认为 SDT 会说吃美味的饼干是内在动机活动的一个例子。相反,SDT 对内在动机的概念更多是关于参与那些让我们探索、扩展和发展自己能力的活动(而且这些活动也恰好非常令人享受!)。

Up until fairly recently – when I started to make a habit of subsuming myself in different research literatures for many weeks at a time (as you do) – I had never come across SDT before. Given the amount and type of content I consume, I have no idea why this is the case.

直到最近——当我开始习惯于一次花上数周时间沉浸在不同的研究文献中(就像你一样)——我之前从未接触过 SDT。考虑到我所消费的内容的数量和类型,我完全不知道为什么会这样。

SDT is a massive area of study.

SDT 是一个庞大的研究领域。

There are thousands of researchers working in this space. Thousands (?) of studies have been conducted. Multiple millions of citations have been accrued.

在这个领域有成千上万的研究人员在工作。已经进行了数千(?)项研究。累积了数百万次引用。

As far as I can see, SDT has been developed slowly and patiently, with a sound scientific methodology. Its theories have been arrived at inductively, and they have been revised and refined to account for the best available empirical research. Many of its core findings do seem to replicate and show up consistently within large-scale meta-analyses.

就我所见,SDT 的发展缓慢而耐心,采用的是稳健的科学方法论。其理论是通过归纳得出的,并且为了解释最佳的实证研究而不断修订和完善。它的许多核心发现似乎确实能够在大规模的元分析中反复出现并保持一致。

What’s more, if you put any stake in h-indices – a measure of a researcher’s impact and productivity – the founders of SDT theory are some of the most influential scholars alive.

更重要的是,如果你重视 h 指数——一种衡量研究者影响力和生产力的指标——那么 SDT 理论的创始人是当今最具影响力的学者之一。

For reference, father of modern linguistics Noam Chomsky has a h-index of 196. Richard Dawkins has a h-index of 83.

作为参考,现代语言学之父诺姆·乔姆斯基(Noam Chomsky)的 h 指数为 196。理查德·道金斯(Richard Dawkins)的 h 指数为 83。

The founders of SDT, E. L. Deci and Richard Ryan, have h-indices of 180 and 229, respectively.

SDT 的创始人 E. L. Deci 和 Richard Ryan 的 h-index 分别为 180 和 229。

So, like, point being: SDT does seem to be a legitimate scientific enterprise, and yet outside of certain academic circles, its ideas don’t receive any air time at all.

所以,重点是:SDT 似乎确实是一项合法的科学事业,然而在某些学术圈子之外,它的想法完全没有得到任何关注。

I don’t know why – and I’ve not been able to find anything online to explain this to my satisfaction.

我不知道为什么——而且我在网上也找不到任何能让我满意的解释。

But regardless: 但无论如何:

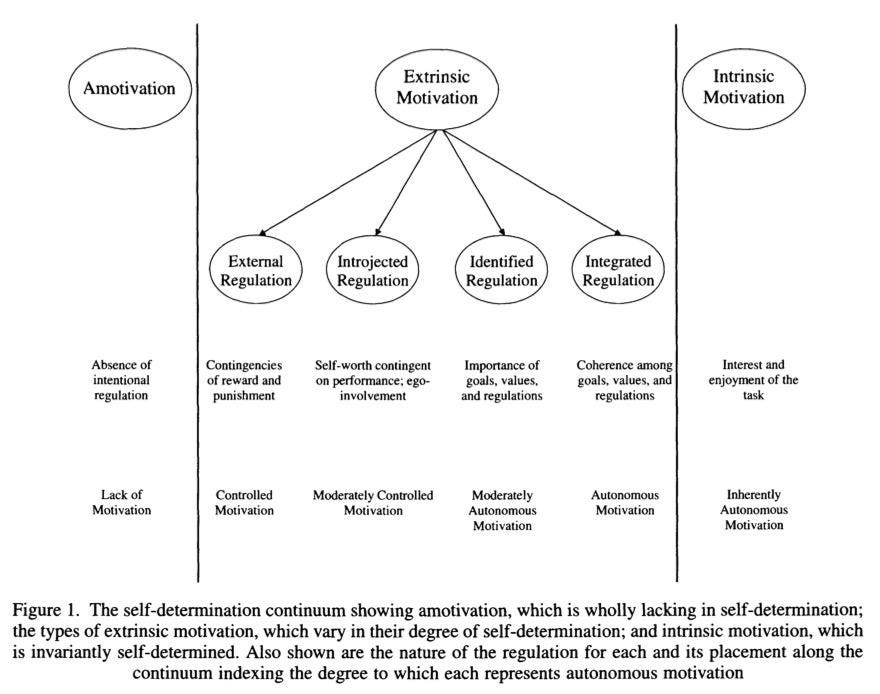

The SDT view of motivation, which we’ll tentatively be adopting from here on out, views motivation as a spectrum ranging from most to least autonomous.

SDT 的动机观点,我们从现在开始将暂时采纳这一观点,认为动机是一个从最自主到最不自主的谱系。

Here’s a diagram: 这里有一个图表:

On the high autonomy end, you have intrinsic motivation, i.e. behaviours that are more or less entirely engaged in for their own sake.

在高度自主的一端,你有内在动机,即行为或多或少完全是为了自身而进行。

Slightly lower down, you have behaviours that are extrinsically motivated but highly autonomous. For example, let’s say that I grew up in a Christian household and that I eventually came to endorse and enact a Christian ethic. By SDT’s lights, behaviours that flow from this ethic would be classed as extrinsically motivated, because they came from an external source – namely, my formative environment – but they would also be classed as highly autonomous, because I engage in them freely and willingly. They are self-endorsed.

稍微低一点的层次,你会发现一些外在动机驱动但高度自主的行为。例如,假设我成长在一个基督教家庭中,最终我接受并践行了一种基督教伦理。根据自我决定理论(SDT)的观点,这种伦理引发的行为会被归类为外在动机驱动,因为它们来源于外部——也就是我成长的环境——但同时也会被归类为高度自主,因为我是自由且自愿地参与其中的。它们是我自我认可的。

A little further along the spectrum, you then get lower autonomy forms of extrinsic motivation. For example, let’s imagine that I grew up in a Christian household but that I did not come to assimilate the Christian ethic that I grew up around. Now, when I visit my family, I might find myself adhering to certain Christian norms, but I would only be doing so to avoid criticism or argument, rather than because I actively endorse these regulations.

在这个范围的稍远处,你会发现较低自主性的外在动机形式。例如,假设我成长在一个基督教家庭,但我并没有完全接受我周围的基督教伦理。现在,当我拜访家人时,我可能会发现自己遵循某些基督教规范,但我这样做只是为了避免批评或争吵,而不是因为我积极支持这些规定。

And then all the way off to the left of the spectrum, you have amotivation, which is where you simply have zero motivation – neither intrinsic or extrinsic – to do something.

然后在光谱的最左端,你会发现无动机状态,也就是你完全没有动力——无论是内在的还是外在的——去做某件事。

One point worth making before we move on is this:

在我们继续之前,有一点值得一提:

SDT assumes that most behaviours are motivated by a mix of these motivation types. As a general rule, the more autonomous forms of motivation are better: they are experienced as being far less effortful, and they are associated with greater persistence and superior performance than controlled forms of motivation.

SDT 假设大多数行为是由这些动机类型的混合所驱动的。一般来说,自主形式的动机更好:它们被体验为远不那么费力,并且与更大的坚持和比受控形式的动机更优越的表现相关联。

When I interpret my sudden turn to scholarliness through an SDT lens, here’s my best high-level guess as to what happened: I shifted from the far left side of the spectrum to somewhere much further to the right.

当我通过 SDT 的视角来解读自己突然转向学术性时,我对所发生的事情有一个高层次的猜测:我从光谱的极左端移到了更靠右的位置。

I’m a naturally curious person who enjoys learning. It makes sense that studying interesting subjects would tap into my intrinsic motivation.

我是一个天生好奇的人,喜欢学习。研究有趣的学科会激发我的内在动力,这很合理。

But at the same time, I wasn’t simply studying for curiosity’s sake. I was also studying because I wanted to get good grades, I wanted to outperform my classmates, I wanted to get into a good university, etc.

但与此同时,我并不仅仅是为了好奇而学习。我也为了取得好成绩而学习,我想超越我的同学,我想进入一所好大学,等等。

So intrinsic and extrinsic forms of motivation were probably both in action here.

因此,内在和外在的动机形式很可能都在这里发挥了作用。

The question I’m trying to answer with this piece is: why did this happen when it did?

我试图通过这篇文章回答的问题是:为什么这件事会在那个时候发生?

This question breaks down into two subquestions

这个问题可以分为两个子问题

Why did I suddenly become intrinsically motivated to study?

为什么我突然有了学习的内在动力?Why did I suddenly shift from low to high-autonomy forms of extrinsic motivation?

为什么我突然从低自主性的外在动机转变为高自主性的外在动机?

As you will have gathered by now, this piece is primarily about intrinsic motivation, so you may think that I’m only addressing the first part of this question.

正如你现在所了解的,这篇文章主要是关于内在动机的,所以你可能会认为我只是在回答这个问题的第一部分。

But as it goes, the conditions that SDT posits as being necessary for intrinsic motivation are also the same conditions that it posits as being necessary for high autonomy forms of extrinsic motivation.

但正如所说,SDT 提出的内在动机所必需的条件,也正是它提出的高度自主形式的外在动机所必需的条件。

So by covering the intrinsic motivation research – which is, I should add, the seed from which all subsequent SDT research eventually sprung – we’ll be able to understand the conditions that are conducive to all forms of autonomous motivation.

因此,通过探讨内在动机研究——我应该补充一下,这是所有后续 SDT 研究最终萌芽的种子——我们将能够理解有助于各种形式自主动机的条件。

I’ll circle back to this point later, but thought it was worth flagging now.

我稍后再回到这一点,但觉得现在值得提一下。

2. How do psychologists measure intrinsic motivation?

2. 心理学家如何测量内在动机?

I promise: I will get into the meat of this piece shortly (next section), but before I do, I need to share a quick overview of the way intrinsic motivation is operationalised in lab experiments, because it’s interesting and also maybe not beyond criticism.

我保证:我很快会进入这篇文章的核心内容(下一节),但在此之前,我需要简要概述一下实验室实验中如何操作内在动机的,因为这很有趣,而且可能并非无可指摘。

In the 70s, E. L. Deci – one of the pioneers of intrinsic motivation research – developed the free-choice paradigm to investigate the impact of various rewards and reward contingencies on intrinsic motivation.

在 70 年代,E. L. Deci——内在动机研究的先驱之一——开发了自由选择范式,以研究各种奖励和奖励条件对内在动机的影响。

I’ve read through a fairly wide range of papers in this space, and while the free-choice paradigm is often applied slightly differently in different contexts, there are a number of features that show up in pretty much all of them.

我已经阅读了这个领域内相当广泛的论文,虽然自由选择范式在不同情境下的应用略有不同,但几乎所有论文中都出现了一些共同特征。

First, participants are broken up into at least two groups – the control group and the experimental group(s).

首先,参与者被分成至少两组——对照组和实验组。

In the initial period, both groups are encouraged to engage in some kind of intrinsically interesting task – for example, a puzzle.

在初始阶段,两个小组都被鼓励参与某种内在有趣的任务——例如,一个谜题。

(Note: experimenters use a range of methods to make sure that these intrinsically interesting tasks are actually intrinsically interesting for the participants).

(注:实验者使用一系列方法来确保这些本身就很有趣的任务对参与者来说确实具有内在吸引力)。

During this initial period, the control group are generally left to engage with the task uninterrupted, while the experimental groups are interfered with in some way. This is where the independent variable gets deployed. So, for example, maybe the experimental group are told that they’re going to be rewarded for engaging with the task (independent variable = expectation of reward) – or maybe they’re told that they’re going to be evaluated based on task performance (independent variable = expectation of evaluation).

在这个初始阶段,对照组通常被允许不受干扰地参与任务,而实验组则会以某种方式受到干扰。这就是自变量发挥作用的地方。例如,实验组可能会被告知他们将因参与任务而获得奖励(自变量 = 期待奖励),或者他们可能会被告知将根据任务表现进行评估(自变量 = 期待评估)。

Once the initial period is complete, all participants then enter what is known as the free-choice period. This is where the experimenter leaves the room and participants are left on their own, apparently unobserved, with the task materials.

一旦初始阶段完成,所有参与者将进入所谓的自由选择阶段。在这个阶段,实验者会离开房间,参与者被独自留下,似乎无人观察,他们面前摆放着任务材料。

Of note: there will also usually be a number of other activities or distractions intentionally left in the room – so, for example, in a study with preschoolers, a selection of toys were left in the room; in a study with adults, a selection of magazines.

值得注意的是:房间里通常还会故意留下一些其他的活动或干扰物——例如,在一项针对学龄前儿童的研究中,房间里留下了一些玩具;在针对成人的研究中,则留下了一些杂志。

Within this paradigm, then, intrinsic motivation is measured in two main ways:

在这种范式中,内在动机主要通过两种方式来衡量:

Free choice measure – the amount of time participant’s spend with the ‘intrinsically motivating’ task in the free-choice period. The idea here is that the more intrinsically motivated the participant is to engaged with the task, the longer they will choose to spend on that task when nobody is watching or evaluating them in any way. This is generally taken to be the primary metric of interest.

自由选择测量——参与者在自由选择期间与“内在动机”任务相处的时间量。这里的理念是,参与者对任务的内在动机越强,当无人观察或以任何方式评估他们时,他们选择在该任务上花费的时间就越长。这通常被视为主要的关注指标。Intrinsic Motivation Inventory – basically just a self-report questionnaire to try and get a read on how much the participant finds the task enjoyable and interesting in the free-choice period. This is usually taken to be a sort of supplementary measure.

内在动机量表——基本上只是一个自我报告问卷,试图了解参与者在自由选择期间对任务的享受和兴趣程度。这通常被视为一种补充性测量。

As it turns out, these two measures are only modestly correlated with one another, which seems to have been a topic of some contention within this field. In the largest meta-analysis ever conducted on rewards and intrinsic motivation (see discussion section), these measures mostly moved in the same direction, but their effect sizes varied quite a lot. As far as I’ve been able to work out, the free-choice measure is generally viewed as the most important of the two because it avoids the well-documented shortcomings of self-report measures.

事实证明,这两项指标之间的相关性只是适度的,这似乎一直是该领域内争论的一个话题。在有史以来关于奖励和内在动机所进行的最大规模的元分析中(见讨论部分),这些指标大多朝同一方向变化,但它们的效果大小差异相当大。据我所知,自由选择指标通常被认为在这两者中更为重要,因为它避免了自我报告指标众所周知的缺点。

I have one or two concerns with the way SDT is measured, but i don’t want to get bogged down in the minutiae without first giving you the interesting stuff, so i’ve saved this for the discussion section. Read: is the free-choice measure actually valid?

我对 SDT 的测量方式有一两个担忧,但我不想在给你介绍有趣的内容之前陷入细枝末节,所以我把这个留到了讨论部分。阅读:自由选择测量真的有效吗?

This is probably all you need to know for now.

这可能就是你现在需要知道的全部内容。

So – onto the research!

所以——开始研究吧!

3. What causes – or blocks – intrinsic motivation? A tour through the research

3. 是什么导致或阻碍了内在动机?研究之旅

The earliest experiments on intrinsic motivation were run in 1971 by E. L. Deci. He wanted to understand what would happen to a person’s intrinsic motivation for a task if you offered them a monetary reward for doing it.

最早关于内在动机的实验是由 E. L. Deci 在 1971 年进行的。他想了解如果为完成某项任务提供金钱奖励,会对一个人对该任务的内在动机产生什么影响。

As mentioned already, the behaviourist assumption at the time was that when you reinforce a behaviour, its frequency increases – and also, importantly, that when you remove said reinforcement, the frequency of the behaviour returns to baseline.

正如已经提到的,当时的行为主义假设是,当你强化一种行为时,其频率会增加——而且重要的是,当你移除这种强化时,该行为的频率会恢复到基线水平。

Deci’s experiment was intended to see if these assumptions – particularly the second one – hold up.

Deci 的实验旨在验证这些假设——尤其是第二个假设——是否成立。

In his first free-choice experiment, he asked both groups – the control and the treatment – to work on a Soma Cube puzzle. The treatment group were given a $1 reward for every puzzle they completed, whereas the control group were given nothing – they worked on the puzzle without any expectation of a reward.

在他的第一次自由选择实验中,他要求两组人——对照组和实验组——去解决一个 Soma Cube 拼图。实验组每完成一个拼图就得到 1 美元的奖励,而对照组则没有任何奖励——他们在没有任何奖励期望的情况下解决拼图。

When all participants were then put in the free-choice condition and researchers measured the amount of time they spent with the puzzles, they found that the treatment group – i.e those that had been given the $1 rewards – actually engaged with the puzzles less.

当所有参与者随后被置于自由选择条件下,研究人员测量他们花在拼图上的时间时,发现治疗组——即那些获得 1 美元奖励的人——实际上与拼图互动的时间更少。

So, in other words: when rewards were involved, intrinsic motivation for the task, as measured by the free-choice measure, went below the pre-reward baseline.

所以,换句话说:当涉及到奖励时,通过自由选择测量得出的任务内在动机低于奖励前的基准线。

As I understand things, this was a pretty groundbreaking finding at the time – and behaviourists have been bitching about it ever since. Unfortunately for them – behaviourists, I mean – this was soon replicated with a whole host of different tasks, rewards, reward contingencies, participants, etc., so it does look to be a legitimate thing (although there are still some who hold out against it).

据我所知,这在当时是一个相当突破性的发现——行为主义者从那以后就一直在抱怨这件事。不幸的是,对他们——我是说行为主义者——来说,这很快就被一系列不同的任务、奖励、奖励条件、参与者等重复验证了,所以这看起来确实是一个合理的事情(尽管仍有一些人对此持反对态度)。

(FYI: the observation that extrinsic rewards tend to harm intrinsic motivation is known as the overjustification effect (also sometimes referred to as the undermining effect))

(供参考:外部奖励往往会损害内在动机的现象被称为过度辩解效应(有时也称为削弱效应))

Before diving in any deeper, an interesting nuance should probably be drawn out here: SDT does not claim that rewards always harm motivation. In fact, the SDT view accepts that at the time rewards are being administered, they will often enhance motivation (with certain qualifications). This is why SDT generally holds that rewards can be an effective means of motivating menial, uninteresting tasks.

在深入探讨之前,这里应该指出一个有趣的细微差别:SDT 并不认为奖励总是会损害动机。事实上,SDT 的观点承认,在给予奖励的时候,奖励往往会增强动机(带有某些限定条件)。这就是为什么 SDT 通常认为奖励可以是激励那些琐碎、无趣任务的有效手段。

The key finding here was that rewards harmed subsequent intrinsic motivation for an intrinsically interesting task. This may seem like a pedantic point, but – if true – it has some pretty far reaching implications.

这里的关键发现是,奖励会损害对一个本身有趣的任务的后续内在动机。这可能看起来像是一个学术性的观点,但——如果属实——它具有相当深远的影响。

Take education: should we be rewarding kids for reading?

拿教育来说:我们应该奖励孩子们阅读吗?

The prima facie conclusion of this research is that, no, we probably shouldn’t. Rewards may be an effective means of motivating reading at the time they are present, but when rewards are removed and kids are left to their own devices, they – the rewards – may actually have a deleterious impact on subsequent intrinsic motivation for reading.

这项研究的初步结论是,不,我们可能不应该这样做。奖励可能是在当时激励阅读的有效手段,但当奖励被取消,孩子们只能靠自己时,这些奖励实际上可能会对随后阅读的内在动机产生有害影响。

Saying that: there are many qualifications and quirks to this picture, so let’s keep following the research.

说到这里:这幅图景有许多条件和奇特之处,所以让我们继续关注研究。

(FYI: there have been a huge number of experiments run in this space, so I’m mostly just going to stick to research that’s in line with the general tenor. You’re getting the highlight reel, but rest assured: many replications and meta-analyses have been done here (some of which we’ll cover).)

(顺便提一句:在这个领域已经进行了大量实验,所以我主要会坚持与总体基调一致的研究。你将看到的是亮点集锦,但请放心:这里已经进行了许多重复实验和元分析(其中一些我们会提到)。)

In a bid to begin exploring the impact of different reward contingencies on intrinsic motivation, Deci (1972a) ran a followup study – once again with the same ‘interesting puzzles’ – but this time he paid the treatment group for simply showing up, rather than for each puzzle completed. The control condition was the same as in the original experiment.

为了开始探索不同奖励条件对内在动机的不同影响,Deci(1972a)进行了一项后续研究——再次使用相同的“有趣谜题”——但这次他支付给实验组的报酬是基于他们的到场,而不是每完成一个谜题。控制组的条件与原始实验相同。

Here, it turned out that participants who received a reward for showing up exhibited just as much intrinsic motivation as those that received no reward at all. So, in other words: within this contingency, rewards did not harm intrinsic motivation at all.

在这里,结果显示,那些因为参与而获得奖励的人表现出与完全没有获得奖励的人同样多的内在动机。换句话说:在这种情况下,奖励完全没有损害内在动机。

Lepper, Green, and Nisbett (1973) ran an experiment looking at the impact of different reward contingencies on preschoolers’ intrinsic motivation for a drawing task using ‘attractive materials.’ The study included three groups:

Lepper、Green 和 Nisbett(1973)进行了一项实验,研究不同的奖励条件对学龄前儿童在使用“吸引人的材料”进行绘画任务时的内在动机的影 响。该研究包括三个组:

Treatment group 1 were told that they would receive a ‘good player’ reward (a star and ribbon) if they completed the drawing task. All children in this group received a good player reward.

治疗组 1 被告知,如果他们完成绘画任务,将获得“优秀玩家”奖励(一颗星和一条丝带)。该组的所有儿童都获得了优秀玩家奖励。Treatment group 2 were not told about any rewards beforehand but were then all given a ‘good player’ reward after the drawing task.

治疗组 2 事先未被告知任何奖励信息,但在绘画任务后,他们都获得了“优秀玩家”奖励。The Control group were not told anything and did not receive a ‘good player’ reward.

控制组没有被告知任何信息,也没有收到“优秀玩家”的奖励。

In line with the previous Deci experiment, treatment group 1 showed less intrinsic motivation in the free choice period than the control group – so, once again, rewards undermined intrinsic motivation. But here’s the interesting thing: treatment group 2 showed just as much (if not more) intrinsic motivation in the free choice period as the control group.

与之前的 Deci 实验一致,治疗组 1 在自由选择期间表现出的内在动机少于对照组——因此,奖励再次削弱了内在动机。但有趣的是:治疗组 2 在自由选择期间表现出的内在动机与对照组相当(甚至可能更多)。

So, in other words: if the reward was dangled beforehand, it harmed intrinsic motivation; if it was unexpected, it didn’t.

所以,换句话说:如果奖励是事先悬挂的,它会损害内在动机;如果它是意料之外的,就不会。

The plot thickens.

情节变得更加复杂。

This finding was built upon by Ross (1975), who compared the impact of salient vs. non-salient rewards on children’s intrinsic motivation to play with a drum kit.

这一发现由罗斯(1975)进一步发展,他比较了显著与非显著奖励对儿童玩鼓组的内在动机的不同影响。

One group of children was simply told that they would receive an unknown prize if they engaged with the drum (non-salient reward). The other group were given the same instructions, but they were told that the unknown prize was hidden inside a box that had been placed conspicuously in front of them (salient reward).

一组孩子只是被告知,如果他们与鼓互动,就会得到一个未知的奖品(非显著奖励)。另一组孩子得到了相同的指示,但他们被告知未知的奖品藏在一个显眼地放在他们面前的盒子里(显著奖励)。

Turns out that the group with the salient reward showed significantly less intrinsic motivation in the free choice period than the group with the non-salient reward. Ross concluded that the salience of the reward seems to modulate its impact: the more salient, the stronger the deleterious effect on intrinsic motivation.

结果显示,奖励显著的组在自由选择期间的内在动机明显低于奖励不显著的组。Ross 得出结论,奖励的显著性似乎会调节其影响:奖励越显著,对内在动机的负面影响就越强。

I’ll share one more experiment – because it adds texture to this picture, plus it touches on the topic of reading motivation – and then I’ll give a rundown of how SDT has accounted for all of these findings.

我将分享另一个实验——因为它为这幅图景增添了层次感,而且它涉及阅读动机的话题——然后我会概述自我决定理论(SDT)是如何解释所有这些发现的。

Marinek and Cambrell (2008) were interested in third-grade children’s reading motivation. They compared a no-reward condition with a token-reward condition – kids received something like a star or a sticker for reading – and found that the token rewards significantly reduced intrinsic motivation for reading.

Marinek 和 Cambrell(2008)对三年级儿童的阅读动机感兴趣。他们比较了无奖励条件和代币奖励条件——孩子们因阅读而获得类似星星或贴纸的东西——并发现代币奖励显著降低了阅读的内在动机。

Based on the other research above, this isn’t a major surprise – but here’s where it gets interesting:

根据上面的其他研究,这并不是一个大惊喜——但有趣的地方来了:

They also ran a third condition where they rewarded children with a book rather than a token. This time round, the reward had no negative effect on intrinsic motivation at all. The explanation put forward in the paper was that rewards that are more proximal to the desired behaviour – e.g. books for reading or, say, paint brushes for painting – do not have the same negative impact on intrinsic motivation as token rewards like money or stickers.

他们还进行了第三个条件实验,在这个条件下,他们用一本书而不是一个代币来奖励孩子们。这一次,奖励对内在动机完全没有负面影响。论文中提出的解释是,与期望行为更直接相关的奖励——例如,阅读奖励书籍,或者绘画奖励画笔——对内在动机的负面影响不像金钱或贴纸等代币奖励那样明显。

OK , so, so far we’ve got:

好的,到目前为止我们有:

Rewards reduce intrinsic motivation

奖励会降低内在动机Rewards only reduce intrinsic motivation when they’re contingent on task completion but not when they’re contingent on simply showing up.

奖励只有在与任务完成挂钩时才会降低内在动机,而在仅仅与出现挂钩时则不会。Salient rewards harm intrinsic motivation, but non-salient ones don’t (or, at least, not as much)

显著的奖励会损害内在动机,但不显著的奖励则不会(或者,至少不会那么严重)Token rewards harm intrinsic motivation, but rewards that relate closely to the task at hand don’t

代币奖励会损害内在动机,但与手头任务密切相关的奖励则不会

How do we reconcile these findings?

我们如何调和这些发现?

SDT’s answer, in a word: autonomy.

SDT 的答案,用一个词来说:自主。

Rewards and reward contingencies that preserve or enhance an individual’s sense of autonomy have a positive impact on intrinsic motivation; those that diminish an individual’s sense of autonomy and that are experienced as an attempt to control their behaviour have a negative impact on intrinsic motivation.

奖励和奖励条件如果能够保持或增强个体的自主感,就会对内在动机产生积极影响;那些削弱个体自主感并被体验为试图控制其行为的奖励和条件,则会对内在动机产生负面影响。

Interpreting these findings through this lens, then:

通过这种视角来解读这些发现,那么:

In the first Deci experiment, where individuals were rewarded with $1 for each puzzle completed, it’s argued that the monetary reward was experienced by participants (whether consciously or not) as a means of controlling their behaviour. This resulted in a reduction in autonomy, which subsequently led to a decline in intrinsic motivation.

在第一次 Deci 实验中,参与者每完成一个谜题就能获得 1 美元的奖励,有人认为这种金钱奖励被参与者(无论是有意识还是无意识地)体验为一种控制他们行为的方式。这导致了自主性的降低,进而导致了内在动机的下降。In the second Deci study, where individuals were given a monetary reward for showing up but not for completing the puzzles, it’s argued that the monetary reward was not experienced by participants as a means of controlling their behaviour – since they’d get the reward regardless of whether or not they completed any puzzles – which is why it didn’t impact intrinsic motivation.

在第二次 Deci 研究中,参与者因出席而获得金钱奖励,而非因完成谜题而获得奖励,因此有人认为金钱奖励并未被参与者视为控制其行为的一种手段——因为无论他们是否完成任何谜题都会获得奖励——这就是为什么它没有影响内在动机。In the Lepper, Green, and Nisbett study, where individuals in treatment 1 were told they would receive a ‘good player’ reward if they performed well, it’s argued that the expectation of evaluation and the dangling of a reward was interpreted as a means of controlling their behaviour. This likewise resulted in a reduction in autonomy and intrinsic motivation.

在 Lepper、Green 和 Nisbett 的研究中,治疗组 1 的个体被告知如果他们表现良好将获得“优秀玩家”奖励,有人认为对评估的期待和奖励的诱惑被解读为控制他们行为的一种手段。这同样导致了自主性和内在动机的减少。But in the same study, for treatment 2, where individuals were not forewarned about the ‘good player’ reward – but where they received the reward nonetheless – it’s argued that the activity was engaged in autonomously – without any external control – and that intrinsic motivation was therefore unaffected.

但在同一项研究中,对于治疗方案 2,个体并未被事先告知关于“优秀玩家”奖励的情况——但他们仍然获得了奖励——有人认为这种活动是自主进行的——没有任何外部控制——因此内在动机未受影响。

So, with the autonomy element of the theory in place – there are a few more key components that still need to be introduced – we can then begin taking a look at experiments that actively seek to manipulate this variable.

因此,随着理论中的自主性元素的确立——还有几个关键组成部分需要介绍——我们就可以开始关注那些积极寻求操控这一变量的实验。

Here are two interesting examples, plus a meta-analysis for good measure:

这里有两个有趣的例子,外加一个元分析以作补充:

Zuckerman, Porac, Lathin, Smith, and Deci (1978) used the standard free-choice paradigm, but they allowed one group of participants to choose which puzzles they engaged with – plus how they allotted their time between them – while the other group were yoked to the choices of a randomly selected counterpart from the first group. Turns out that participants from the first group, i.e. those who got to choose, showed significantly more intrinsic motivation in the free choice period. I’ve come across a handful of other studies that show the same thing: introducing choice often seems to improve performance.

Zuckerman、Porac、Lathin、Smith 和 Deci(1978)使用了标准的自由选择范式,但他们允许一组参与者选择他们参与的谜题——以及如何在这些谜题之间分配时间——而另一组参与者则被绑定到第一组中随机选择的对应者的选择上。结果显示,第一组的参与者,即那些能够自己选择的参与者,在自由选择期间表现出明显更高的内在动机。我还看到过其他几项研究显示了同样的结果:引入选择往往似乎能提高表现。This one isn’t strictly about the relationship between choice and intrinsic motivation, but I thought I’d throw it in anyway because it’s closely related and also interesting: Murayama et al (2015) had participants play a game where they were challenged to pause a stopwatch within 50 milliseconds of the 5-second mark. One group was allowed to choose which stopwatch they used (there were a number of different options); the other group were assigned a stopwatch at random. While this was going on, all participants were put in an fMRI to see what was going on in their brains. Turns out that performance was better in the choice condition. That participants in the choice condition were more resilient to negative feedback. That participants in the choice condition showed no drop in ventromedial PFC activity following failure, but there was a drop in vmPFC activity for participants in the no-choice condition.

这一项研究并不是严格关于选择与内在动机之间的关系,但我还是决定把它加进来,因为它与此密切相关且很有趣:Murayama 等人(2015 年)让参与者玩一个游戏,挑战他们在 5 秒标记的 50 毫秒内暂停秒表。一组参与者可以选择他们使用的秒表(有多种不同选项);另一组参与者则被随机分配一个秒表。在这个过程中,所有参与者都被置于 fMRI 中,以观察他们大脑中的活动。结果显示,选择条件下的表现更好。选择条件下的参与者对负面反馈的韧性更强。选择条件下的参与者在失败后 ventromedial PFC 活动没有下降,而无选择条件下的参与者 vmPFC 活动则有所下降。Patall, Cooper, and Robinson (2008) ran a meta-analysis with 41 studies to examine the effects of choice on intrinsic motivation and related outcomes. They found robust effects showing that choice enhances intrinsic motivation in both adults and children.

Patall、Cooper 和 Robinson(2008)进行了一项包含 41 项研究的元分析,以考察选择对内在动机及相关结果的影响。他们发现,选择对成人和儿童的内在动机都有显著的增强作用。

So, there you have it:

所以,这就是:

As predicted, when we give people more choice – when you increase their sense of autonomy – it boosts their intrinsic motivation (and performance too).

正如预测的那样,当我们给予人们更多选择——当你增强他们的自主感时——这会提升他们的内在动机(以及表现)。

I have a few qualms with the whole autonomy angle – to be discussed in the discussion section (where else!) – but when I try to match this up against my own experiences with intrinsic motivation, it fits pretty well.

我对整个自主性角度有一些疑虑——将在讨论部分中讨论(还能在哪儿呢!)——但当我尝试将其与我自己关于内在动机的经历相对照时,它非常契合。

Take, once again, the monomaniacal study spree discussed in the intro to this piece.

再一次以本文开篇讨论的那种偏执狂式的学习狂热为例。

During my GCSEs, i.e. before I started working like a madman, my parents and teachers exerted constant pressure on me to study. As a result, my studies never felt self-motivated – autonomy was in the gutter – and I had zero intrinsic motivation.

在我参加 GCSE 考试期间,也就是在我开始像疯子一样工作之前,我的父母和老师不断给我施加压力让我学习。因此,我的学习从来都不是出于自我驱动——自主性完全被扼杀——我也没有任何内在的动力。

But when I moved into year 12 – which is when the monomania began – there was a big and definite uptick in the amount of autonomy I was being offered. To give a few examples:

但当我进入 12 年级时——也就是我的偏执开始的时候——我被给予的自主权有了明显且大幅的增加。举几个例子:

Uniform – we were no longer assigned a uniform. There was a sixth form dress code, but within this dress code there was a fair amount of scope to choose what we wore.

制服——我们不再被分配制服。有一个六年级的着装规范,但在这个规范内,我们有相当大的空间选择穿什么。Exams – at the start of sixth form, there was an extended respite from the pressure that came with our GCSEs. This armistice might have given me enough space to begin generating my own motivation for school.

考试——在六年级开始时,我们从 GCSE 带来的压力中获得了一段长时间的喘息。这段休战可能给了我足够的空间,开始为学校产生自己的动力。Ambient climate – teachers started to treat us like adults that could be listened to and respected, rather than drones that needed to be coerced into compliance. We were allowed to leave the school grounds at lunch. We had free periods, in which we could do more or less whatever we wanted. Some of us even started getting cars.

环境氛围——老师们开始把我们当作可以倾听和尊重的成年人,而不是需要被强迫服从的无人机。我们被允许在午餐时间离开学校。我们有自由时间,在这段时间里我们可以或多或少做任何我们想做的事。有些人甚至开始拥有自己的车。

So, yeah, in sum: my explosion in motivation does seem to coincide with a sharp uptick in autonomy.

所以,总的来说:我的动力爆发似乎确实与自主性的急剧提升相吻合。

This still doesn’t explain everything though: for example, why did I specifically become monomaniacal about school? Why not something else – like, say, video games or football or puzzles?

这仍然无法解释一切:例如,为什么我特别对学校变得偏执?为什么不是其他东西——比如说,电子游戏、足球或者拼图?

By introducing further elements in the SDT theory, I think we can start to explain some of this.

通过在 SDT 理论中引入更多元素,我认为我们可以开始解释其中的一些内容。

—

Assuming SDT is true, so far we’ve established that when rewards are experienced as controlling , i.e. when they infringe upon an individual’s sense of autonomy, they have a negative impact on intrinsic motivation.

假设 SDT 是正确的,到目前为止我们已经确定,当奖励被体验为控制性的,即当它们侵犯了个人的自主感时,会对内在动机产生负面影响。

But what about verbal rewards? Do they count?

但是口头奖励呢?它们算数吗?

This is important, since a massive percentage of the rewards we receive and dispense in life are of this kind.

这很重要,因为我们在生活中获得和给予的奖励中有很大一部分是这种类型的。

The previous operant paradigm would have us believe that verbal rewards are likely to reinforce a behaviour and thereby increase its frequency. So, for example, if a kid does something good – like e.g. sharing their toys with their siblings – we ought to praise them. But maybe, as per the research above, this isn’t the case?

先前的操作范式让我们相信,口头奖励可能会强化某种行为,从而增加其发生的频率。所以,例如,如果一个孩子做了好事——比如与兄弟姐妹分享玩具——我们应该表扬他们。但根据上述研究,也许情况并非如此?

In much of the early research on verbal rewards and intrinsic motivation, participants were placed in the standard free-choice paradigm and given positive verbal feedback for working on an activity. For example, if they completed the activity, they were told ‘you did very well in completing the task; many people did not.’ If they failed to complete the activity, they were told ‘this was a very difficult task but you were progressing well with it.’

在关于口头奖励和内在动机的早期研究中,参与者被置于标准的自由选择范式中,并因参与某项活动而获得积极的口头反馈。例如,如果他们完成了活动,会被告知“你在完成任务方面表现得非常好;很多人没有做到。”如果他们未能完成活动,则被告知“这是一项非常困难的任务,但你在其中进展得很好。”

Turns out that participants who were given positive feedback generally displayed MORE free-choice persistence, i.e. intrinsic motivation, than those weren’t given any feedback at all.

结果表明,获得正面反馈的参与者通常表现出更多的自由选择坚持,即内在动机,相比那些完全没有得到任何反馈的人。

We’ve just learned that token rewards have a negative impact on intrinsic motivation; now we’re finding out that verbal rewards apparently do the opposite. Again, given the research discussed so far, this isn’t what we’d expect at all.

我们刚刚了解到,代币奖励对内在动机有负面影响;现在我们发现,口头奖励显然起到相反的作用。再次,根据目前讨论的研究,这完全不是我们所预料的。

Does SDT have a means of reconciling these findings?

SDT 有办法调和这些发现吗?

You betcha – but it needed to introduce another component to its theory in order to do so: competence.

当然可以——但它需要在其理论中引入另一个组成部分才能做到这一点:能力。

All things being equal, if a reward signals that its recipient is competent with respect to a given activity or task, it will have a positive impact on intrinsic motivation for that task/activity.

在所有条件相同的情况下,如果奖励表明其接受者在某项活动或任务上表现出色,那么它将对该任务/活动的内在动机产生积极影响。

So, for example, let’s say I’m learning to paint. I spend an hour brushing away at my canvas, and at the end of the session, my instructor says something to the effect of ‘you have a wonderful eye for colour’ (or whatever a painting instructor might say to a pupil!).

所以,举个例子,假设我正在学习绘画。我花了一个小时在画布上涂抹,课程结束时,我的导师说了类似“你对色彩有很棒的眼光”这样的话(或者绘画导师可能会对学生说的其他话!)。

This feedback serves as a signal that I am competent and therefore bolsters my intrinsic motivation for painting (which, I guess, is kind of what our folk psychology would predict?).

这种反馈作为一个信号,表明我是有能力的,因此增强了我对绘画的内在动力(我想,这有点符合我们的民间心理学的预测?)。

But here’s the thing: the vast majority of rewards and reward contingencies affect competence and autonomy at the same time. Take this experiment:

但问题是:绝大多数的奖励和奖励条件同时影响能力和自主性。拿这个实验来说:

Smith (1975) assigned three groups to a learning task about Art History. One group was told beforehand that they were going to receive a written evaluation; the other two weren’t. Of those who weren’t, one group received an unanticipated evaluation after the learning task – one didn’t. Unbeknownst to all participants, everybody that received an evaluation received a positive one. As per usual, they were all then observed in a free-choice period to see how much they engaged with the original task when left to their own devices.

史密斯(1975)将三个小组分配到一个关于艺术史的学习任务中。其中一个小组事先被告知他们将接受书面评估;另外两个小组则没有被告知。在没有被告知的小组中,一个小组在学习任务后收到了意想不到的评估,而另一个小组没有。所有参与者都不知道,凡是收到评估的人都得到了积极的评价。按照惯例,他们随后都在一个自由选择的时间段内被观察,以了解他们在无人干涉的情况下对原始任务的参与程度。

The main finding here was that those in the first group – i.e. those who were told beforehand that they would be evaluated and who then received a positive evaluation – displayed significantly less intrinsic motivation than either of the other groups.

这里的主要发现是,第一组的人——即那些事先被告知将被评估并随后获得正面评价的人——表现出的内在动机明显低于其他两组。

SDT would explain this result by saying that the anticipated evaluation negatively affected autonomy while positively affecting competence. This then netted out at a slight reduction in intrinsic motivation. In contrast, the unanticipated evaluation had no negative effect on autonomy, but a positive effect on competence – which netted out as an increase in intrinsic motivation.

SDT 会解释这一结果,认为预期的评价对自主性产生了负面影响,同时对能力感产生了正面影响。这最终导致内在动机略有减少。相比之下,未预期的评价对自主性没有负面影响,但对能力感有正面影响——最终导致内在动机增加。

This is generally how SDT understands most rewards and rewards contingencies: rewards that signal competence are conducive to intrinsic motivation, but unfortunately, many rewards also inadvertently impair autonomy – which is why they so often seem to harm intrinsic motivation.

这通常是 SDT 对大多数奖励和奖励条件性的理解方式:表明能力的奖励有助于内在动机,但不幸的是,许多奖励也会无意中损害自主性——这就是为什么它们常常似乎会损害内在动机。

Returning once again to the example of my monomaniacal study spree: this all tracks really nicely.

再次回到我那偏执的学习狂热的例子:这一切都非常吻合。

Why did I become obsessive about studying rather than other things?

为什么我会痴迷于学习而不是其他事情?

Because I was good at it.

因为我很擅长这个。

Once my teachers and parents stepped back, my sense of autonomy increased. This freed up some autonomous motivation for studying, and as soon as I started to put in the work, my results improved radically. Improved results were a strong competence signal, which freed up even more motivation. More motivation = even better results = even more motivation = even better results, etc.

一旦我的老师和父母退后一步,我的自主感就增强了。这释放了一些学习的自主动力,一旦我开始投入努力,我的成绩就有了显著的提高。成绩的提高是一个强烈的能力信号,这又释放了更多的动力。更多的动力=更好的成绩=更多的动力=更好的成绩,等等。

But there was also another dynamic at play: the better my grades became, the more relaxed my teachers and parents became. This meant they gave me a lot more breathing space to do my own thing – read: more autonomy. Even more autonomy = even more intrinsic motivation = even more autonomy, etc.

但还有另一种动态在起作用:我的成绩越好,老师和父母就越放松。这意味着他们给了我更多的自由空间去做自己的事情——也就是说:更多的自主权。更多的自主权 = 更多的内在动力 = 更多的自主权,等等。

As far as I can see, I was essentially locked inside multiple feedback loops.

就我所见,我基本上被困在多个反馈循环中。

—

If you’ve ever done any reading in and around SDT, you’ll know that the theory identifies three psychological needs – not two.

如果你曾经在 SDT 及其相关领域做过任何阅读,你会知道该理论确定了三种心理需求——而不是两种。

Autonomy and competence are the first and the second.

自主性和能力是第一和第二。

Relatedness is the third.

相关性是第三个。

Relatedness is all about how connected we feel to those around us.

关联性完全是关于我们与周围人联系的感觉。

Turns out that relatedness is another extremely important component in SDT’s model of intrinsic motivation. This particular element of the theory was stumbled upon accidentally, and the story’s pretty interesting, so I thought I’d tell it:

事实证明,相关性是 SDT 内在动机模型中另一个极其重要的组成部分。理论中的这个特定元素是偶然发现的,故事非常有趣,所以我想讲一讲:

Anderson, Manoogian, and Reznick (1976) were examining the effects of rewards and feedback on young children’s intrinsic motivation. The usual fare.

Anderson、Manoogian 和 Reznick(1976)研究了奖励和反馈对幼儿内在动机的影响。常见的研究内容。

In a bid to create a condition with neither positive nor negative feedback, they instructed researchers within this condition to remain silent and unresponsive to any overtures from the children. As a no-reward, no-feedback condition, we’d expect this to have a fairly neutral impact on intrinsic motivation – but this isn’t what happened at all:

为了创造一个既没有正面反馈也没有负面反馈的条件,他们指示在这种条件下的研究人员对孩子们的任何主动行为保持沉默和无反应。作为一个无奖励、无反馈的条件,我们预期这对内在动机的影响会是相当中性的——但事实完全不是这样:

Children in this group showed less intrinsic motivation than any group in the study – including those who received negative feedback!

这个组的孩子表现出比研究中任何组都低的内在动机——包括那些收到负面反馈的组!

It was theorised that these children felt rejected by the researchers, which thwarted their need for relatedness and thereby destroyed any intrinsic motivation they may have had for the task.

有人推测,这些孩子感到被研究人员拒绝,这挫伤了他们对关联的需求,从而破坏了他们对任务可能拥有的任何内在动机。

Plenty of later research supports this idea, e.g.

大量的后续研究支持了这一观点,例如

Ryan, Stiller, and Lynch (1994) surveyed a large group of junior high students. They found that students who felt security with teachers (and other figures in their lives) were more engaged with school work and exhibited higher levels of intrinsic motivation.

Ryan、Stiller 和 Lynch(1994)调查了一大群初中生。他们发现,那些对老师(以及生活中其他人物)感到安全感的学生,对学业更加投入,并且表现出更高水平的内在动机。Bao and Lam (2008) looked at the importance of autonomy and relatedness for intrinsic motivation to study in Chinese students. They found that kids who make their own choices, rather than having them made for them show higher levels of intrinsic motivation, but that this was mediated by how close these children felt to their parents. If they were close, then choice was less important and they showed just as much intrinsic motivation as their higher autonomy peers.

Bao 和 Lam(2008)研究了自主性和关联性对中国学生学习内在动机的重要性。他们发现,孩子们如果能自己做选择,而不是由他人替他们决定,会表现出更高水平的内在动机,但这种动机受到他们与父母亲密程度的中介影响。如果他们与父母关系亲密,那么选择的重要性就较低,他们表现出的内在动机与那些自主性较高的同龄人相当。This theory also lines up very neatly with Bowlby’s attachment theory: babies that are more securely attached to their primary caregivers demonstrate greater curiosity and tendency to explore.

这个理论也与鲍尔比的依附理论非常吻合:与主要看护者有更安全依附关系的婴儿表现出更大的好奇心和探索倾向。

So, there you go:

所以,就是这样:

Relatedness = super important.

相关性 = 超级重要。

But one question you might still have is: how important?

但你可能仍然有一个问题:有多重要?

After all, many activities that seem to be fuelled by intrinsic motivation – things like reading, hiking, etc. – are solitary. Solitary activities, by definition, do not involve relating to others, so how can relatedness be involved here?

毕竟,许多看似由内在动机驱动的活动——比如阅读、徒步等——都是独自进行的。独自进行的活动,顾名思义,不涉及与他人的联系,那么 relatedness 又如何能参与其中呢?

SDT’s stance, so far as I can work it out, is that relatedness is often a background requirement for intrinsic motivation. Relatedness doesn’t necessarily have to be tied to each and every intrinsically motivated activity – although it sometimes helps. If your life generally meets your requirement for relatedness, then you will have readier access to intrinsic motivation across all activities.

SDT 的立场,据我所知,是相关性通常是内在动机的一个背景要求。相关性不一定非要与每一个内在动机活动挂钩——尽管有时候这会有所帮助。如果你的生活总体上满足了你对相关性的需求,那么你将更容易在所有活动中获得内在动机。

So, bringing this back one last time to my own experience at school: I personally feel like autonomy and competence are more operative than relatedness in my case – but I would also say this:

所以,最后一次回到我在学校的经历:我个人觉得自主性和能力在我的情况下比关系性更起作用——但我也会这样说:

During sixth form, almost everyone in my former friendship group left the school. This former friendship group, for reference, wasn’t great. If it was being scored on its ability to satisfy my need for relatedness, it would probably get a 3 out of 10.

在第六学年期间,我之前的朋友圈子里几乎所有人都离开了学校。顺便提一下,这个之前的朋友圈子并不怎么样。如果要根据它满足我对归属感需求的能力来打分,它大概只能得 10 分中的 3 分。

As a result of this disbanding, I was then forced to join a new friendship group, and I would say that those new relationships did a much better job of meeting my need for relatedness. Maybe 7 or 8 out of 10.

由于这次解散,我被迫加入了一个新的朋友圈,我得说这些新关系在满足我对归属感的需求方面做得好多了。大概有 7 到 8 分,10 分满分。

There’s also just the general point to make, which is that when I was studying hard, I was in harmony with my parents and my teachers. My aspirations for my life lined up closely with theirs’, and this improved the quality and closeness of those relationships.

还有一个普遍的观点要说,那就是当我努力学习时,我与父母和老师的关系是和谐的。我对生活的抱负与他们的期望紧密相符,这改善了那些关系的质量和亲密度。

It seems, then, that competence may also have played an important role in my studies too – and that the feedback loop may have more layers to it than previously assumed.

看来,能力在我的研究中可能也扮演了重要角色——而且反馈循环可能比之前假设的具有更多层次。

—

For the record: all of the research and theory discussed in this section is actually taken solely from one of the six mini-theories that make up SDT. This particular mini-theory is called Cognitive Evaluation Theory (CET), and the other five are mostly just an extension of these core ideas.

为记录在案:本节讨论的所有研究和理论实际上仅来源于构成 SDT 的六个小型理论之一。这个特定的小型理论被称为认知评价理论(CET),其他五个理论大多只是这些核心思想的扩展。

觉得这张图片可能有用,从这里借来的。不知道为什么他们没有包括这六个关于相关性动机理论(RMT)的迷你理论的 th 。

So: according to CET, intrinsic motivation is determined by the interplay of three key factors: autonomy, competence, and relatedness.

因此:根据 CET,内在动机由三个关键因素的相互作用决定:自主性、能力感和关联性。

There are some finer points and concerns that we’ll dig into in the next section, but this is the big picture theory – and actually, all things considered, I think it does quite an impressive job of mapping onto some of my own experiences with intrinsic motivation.

有一些更细致的要点和关注点我们将在下一部分深入探讨,但这是整体理论的大框架——而且,综合考虑所有因素,我认为它在映射到我自己关于内在动机的某些经历方面做得相当令人印象深刻。

4. Discussion: concerns, criticisms, and miscellaneous ideas

4. 讨论:关注点、批评和杂项想法

As will hopefully be clear at this point, I’m fairly convinced that SDT is getting at something real – but there are a few parts of the theory that I’m not quite bought into – or that I think might need refining.

希望此时已经很清楚,我相当确信 SDT 确实触及了一些真实的东西——但理论中有几个部分我还没有完全接受——或者我觉得可能需要进一步完善。

I’m no expert, so take these speculations with a hearty pinch of salt. It may well be the case that people have tackled and refuted these ideas and objections already.

我不是专家,所以请对这些推测持保留态度。很可能已经有人提出并反驳了这些想法和反对意见。

There are also a couple of other things that I didn’t touch on during previous sections but that I think are either important or interesting, so I’ve thrown them into this section too.

还有一些其他的事情,我在之前的部分没有提到,但我认为它们要么很重要,要么很有趣,所以我也把它们放进了这一部分。

1. An alternative theory: dopamine’s impact on intrinsic motivation

1. 另一种理论:多巴胺对内在动机的影响

As some of you will know, a while ago I did a bit of a deep dive on dopamine, the neurochemical linked to motivation, learning, and reward. I’m not a world authority on this subject by any means, so treat my speculation here with the level of skepticism it deserves. Nonetheless, I think the dopamine angle offers a slightly different – and, I think, quite compelling – way of interpreting some of the experimental findings from this literature.

正如你们中的一些人所知,不久前我对多巴胺进行了一些深入研究,这种神经化学物质与动机、学习和奖励有关。我绝不是这个领域的世界权威,所以请以应有的怀疑态度对待我这里的推测。尽管如此,我认为从多巴胺的角度来看,可以提供一种略有不同——而且我认为相当有说服力——的方式来解读这篇文献中的一些实验结果。

First, a quick tl;dr on the dopamine piece:

首先,关于多巴胺部分做一个快速的简要总结:

When we receive a reward for completing a task, we experience a dopamine spike in certain ‘reward centres’ of the brain. Contrary to the lay view, this spike does not seem to be causing pleasure: it seems to be causing learning. In other words, dopamine seems to stamp in the relationship between stimulus, behaviour, and reward.

当我们因完成任务而获得奖励时,大脑中的某些“奖励中心”会经历多巴胺激增。与普通人的看法相反,这种激增似乎并不是在引发快感:它似乎是在引发学习。换句话说,多巴胺似乎在巩固刺激、行为和奖励之间的关系。

But dopamine is about more than just learning; it’s also about motivation. The next time we encounter the stimuli associated with a reward, dopamine spikes again, this time invigorating the behaviour that previously led to the reward.

但多巴胺不仅仅与学习有关;它还与动机有关。下一次我们遇到与奖励相关的刺激时,多巴胺会再次激增,这一次会激发之前导致奖励的行为。

So, to make this a bit more concrete: let’s say I walk past a sweet shop and I decide to go in and buy a bag of sherbet lemons. When I eat the sherbet lemons, there’s a dopamine spike in my brain, and this stamps in a relationship between the stimuli – the sight of the sweet shop – the behaviour – the act of going in there, buying the sweets, and eating them – and the reward – the enjoyment that came from eating the sherbet lemons.

所以,为了让这个概念更具体一些:假设我路过一家糖果店,我决定进去买一袋柠檬雪宝糖。当我吃柠檬雪宝糖时,我的大脑会产生多巴胺激增,这会在刺激物——看到糖果店、行为——进去买糖果并吃掉它们、以及奖励——吃柠檬雪宝糖带来的享受之间建立一种联系。

Now imagine that a week later I’m walking past this sweetshop. My brain has come to associate these specific stimuli – the sight of the sweetshop – with reward, so it produces a dopamine spike. This dopamine spike then invigorates the behaviour that generated the reward last time – i.e. going into the shop and buying the sweets – and this ultimately results in the reward being obtained again.

现在想象一下,一周后我走过这家糖果店。我的大脑已经开始将这些特定的刺激——看到糖果店——与奖励联系起来,于是它产生了一股多巴胺激增。这股多巴胺激增随后激发了上次带来奖励的行为——也就是走进店里买糖果——最终再次获得了奖励。

But here’s the thing: let’s say that I encounter the stimuli, I perform the behaviour, but the reward is not forthcoming. Like, say: I see the sweetshop, I walk into it, but when I go to the sherbet lemon section, it turns out that there are none left.

但问题是:假设我遇到了刺激,我做出了行为,但奖励并没有到来。比如说:我看到了糖果店,我走了进去,但当我走到柠檬 sherbet 区域时,却发现已经没有了。

What happens? 发生了什么事?

Instead of spiking or staying constant, dopamine goes below baseline.

dopamine 没有飙升或保持恒定,而是低于基线。

当奖励被省略时(底部图表),多巴胺水平会低于基线。

As I understand things, when this occurs, it is in some sense reducing the strength of the relationship between the stimuli, the behaviour, and the reward. This means that the next time I see the sweet shop, there will be a smaller dopamine spike than before, which will reduce the strength of the motivation I feel to go inside and buy the sweets.

据我所知,当这种情况发生时,在某种意义上,它会减弱刺激、行为和奖励之间的关系强度。这意味着下次我看到糖果店时,多巴胺的激增会比之前少,这将减弱我走进店内购买糖果的动机强度。

I think we can use this understanding of dopamine to explain many of the findings from the intrinsic motivation literature without recourse to the core SDT concepts.

我认为我们可以用对多巴胺的这种理解来解释内在动机文献中的许多发现,而无需诉诸 SDT 的核心概念。

Consider once again the original study run by E. L. Deci (1971).

再次考虑一下由 E. L. Deci 在 1971 年进行的原始研究。

I didn’t go into all of the details originally, because it wasn’t really needed, but it is now, so:

我最初没有详细说明所有细节,因为当时并不需要,但现在有必要了,所以:

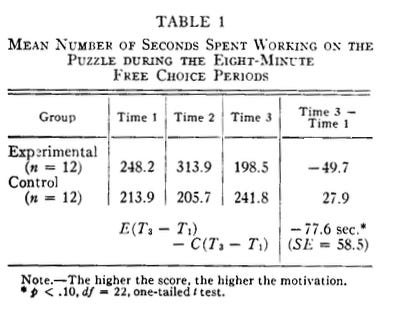

Deci actually had three periods in his experiment. In the first period, all participants did the same thing. From the original paper:

Deci 在他的实验中实际上有三个阶段。在第一个阶段,所有参与者都做同样的事情。原文如下:

‘After they entered the experimental room, they were seated at a table with the puzzle pieces in front of them, three drawings of configurations to the right of them, the latest issues of New Yorker, Time, and Playboy to their left, and the experimenter on the opposite side of the table. They were told that they would spend all three sessions using the pieces of plastic to form various configurations, such as the same they were shown.’

他们进入实验房间后,被安排在一张桌子旁坐下,面前摆放着拼图碎片,右侧是三张配置图,左侧是最新的《纽约客》、《时代》和《花花公子》杂志,实验者坐在桌子的对面。他们被告知将在三个阶段中使用这些塑料碎片组成各种配置,比如他们所看到的那样。

All participants were then asked to reproduce, using the puzzle pieces, the configurations shown in the drawings.

所有参与者随后被要求使用拼图碎片重现图纸中所示的配置。

In the second session, those in the experimental group were told that they would receive a $1 reward for every configuration completed within 13 minutes. Meanwhile, the control group did the exact same thing as in the first session.

在第二轮实验中,实验组的参与者被告知,每在 13 分钟内完成一个配置,他们将获得 1 美元的奖励。与此同时,对照组的表现与第一轮实验完全相同。

And then in the third session, both groups returned to the same conditions as in the first period.

然后在第三次会议中,两个小组都回到了与第一阶段相同的条件。

So for the control it was: no reward, no reward, no reward. For the experimental group is was: no reward, reward, no reward.

所以对于对照组来说是:没有奖励,没有奖励,没有奖励。对于实验组来说是:没有奖励,有奖励,没有奖励。

Now, in order to measure intrinsic motivation, Deci placed an eight minute free-choice period in the middle of each of these sessions. During this time, the experimenter left the room, telling participants ‘I shall be gone only a few minutes, you may do whatever you want while I am gone.’ They could work on the puzzles, read the magazines, stare around the room, etc.

现在,为了测量内在动机,Deci 在每个实验环节中间设置了一个八分钟的自由选择时间。在此期间,实验者会离开房间,并告诉参与者:“我只会离开几分钟,你们可以在我不在的时候做任何想做的事。”他们可以继续解谜题,阅读杂志,环顾房间,等等。

Meanwhile, all participants were monitored to see how long they engaged with the puzzles during each of these free choice periods.

与此同时,所有参与者都被监控,以观察他们在每个自由选择时段内与谜题互动的时间长短。

So, with all of that additional context, here are the results:

因此,在所有这些额外背景信息的基础上,以下是结果:

The interesting thing here – and the reason I think the dopamine explanation is plausible – is this: in the experimental group, free-choice engagement with the task goes way up in the second session, after rewards have first been introduced.

这里有趣的事情——也是我认为多巴胺解释合理的原因——是:在实验组中,在首次引入奖励后,第二次会话中对任务的自由选择参与度大幅上升。

This is what the dopamine account would predict: an association between the puzzles and a monetary reward has been established. As a result, when the participants encounter the puzzle next time, dopamine levels rise to invigorate the behaviour that secured the reward last time, i.e. playing with the puzzles.

这就是多巴胺理论所预测的:谜题与金钱奖励之间建立了一种关联。因此,当参与者下次遇到谜题时,多巴胺水平会上升,以激励上次获得奖励的行为,即玩谜题。

But in the following session, when the monetary rewards are removed, dopamine levels go below baseline, weakening the association between the behaviour (doing the puzzles) and the reward (receiving the money).

但在接下来的环节中,当金钱奖励被取消时,多巴胺水平会低于基线,削弱了行为(解谜)与奖励(获得金钱)之间的关联。

As a result, the individual feels even less motivated to engage in the task than before, which results in free-choice engagement going way down.

因此,个体对参与任务的动机甚至比以前更低,这导致自由选择的参与度大幅下降。

At least for this particular experiment, I find this explanation quite compelling. If anyone knows a reason as to why it’s wrong, I’m all ears!

至少对于这个特定的实验,我觉得这个解释非常有说服力。如果有人知道为什么它是错的,我洗耳恭听!

2. Distraction vs. Autonomy: an alternative explanation

2. 分心与自主:另一种解释

I think there’s good evidence that higher autonomy forms of motivation are superior – in terms of subjective experience, performance, persistence, etc. – than lower forms of autonomy.

我认为有充分的证据表明,较高自主性的动机形式在主观体验、表现、持久性等方面优于较低自主性的形式。

I’m completely on board with this

我完全同意这个想法

But when I look at some of the early experiments surrounding intrinsic motivation, I feel like autonomy as an explanation is a bit of a stretch.

但当我看到一些关于内在动机的早期实验时,我觉得将自主性作为解释有点牵强。

Take the Ross (1975) one, where salient rewards were compared to non-salient rewards.

拿 Ross(1975)的那一项来说,其中显著奖励与非显著奖励进行了比较。

This result is completely plausible to me: it makes sense that if you promise a kid an unknown reward for playing a drum, and then you hide the unknown reward in a box placed conspicuously in front of them, they will experience less enjoyment when they play the drum. And if they experience less enjoyment, it stands to reason that they will probably be less motivated to play with the drum the next time the opportunity presents itself, i.e. a reduction in intrinsic motivation.

这个结果对我来说完全合理:如果你承诺给一个孩子一个未知的奖励来敲鼓,然后把这个未知的奖励藏在一个显眼地放在他们面前的盒子里,他们在敲鼓时会感到更少的乐趣。如果他们感到乐趣减少,那么可以推断,下一次有机会时,他们可能会缺乏动力去玩鼓,也就是说,内在动机减少了。

But here’s the thing: SDT posits that the reason for this reduction in intrinsic motivation is that the highly salient reward is experienced as controlling – as impairing the individual’s sense of autonomy – and that this is ultimately what causes the downturn in intrinsic motivation.

但事情是这样的:SDT 提出,这种内在动机减少的原因是,高度显著的奖励被体验为控制性的——它损害了个体的自主感——而这最终导致了内在动机的下降。

But would these salient rewards really be experienced as a form of control?

但是,这些显著的奖励真的会被体验为一种控制形式吗?

I’m not convinced.

我不相信。

For me, a better explanation is simply that the reward functioned as a distraction, and that the distraction reduced the quality of the attention the kids brought to bear on the task.

对我来说,一个更好的解释是,奖励只是起到了一种干扰作用,而这种干扰降低了孩子们对任务投入的注意力质量。

Think of it like this: tasks that are intrinsically interesting are in some sense a reward unto themselves. But if you offer up highly salient extrinsic rewards for doing these tasks, then each participant’s attention is going to be divided between the task and the reward. This divided attention will impair the quality of the participant’s engagement with the task, which will in turn reduce the amount of enjoyment they’re able to extract from it.

这样想一想:那些本身就很有趣的任务在某种意义上就是一种自我奖励。但如果你为完成这些任务提供非常显著的外部奖励,那么每个参与者的注意力就会在任务和奖励之间分散。这种分散的注意力会损害参与者对任务的投入质量,进而减少他们从中获得的乐趣。

Less enjoyment from the task = reduced time playing with the reward in the free-choice period.

任务带来的乐趣减少 = 在自由选择时间内玩奖励的时间减少。

This seems to me like a much more plausible explanation than the autonomy one.

这对我来说似乎是一个比自主性解释更合理的解释。

For another example, consider the Marinek and Cambrell (2008) experiment where they compared the effect of token-rewards, e.g. a gold star, with task-related rewards, e.g. a book, on reading motivation.

再举一个例子,考虑一下 Marinek 和 Cambrell(2008 年)的实验,他们比较了象征性奖励(例如金星)和任务相关奖励(例如一本书)对阅读动机的效果。

Would the reward of a book really be experienced as less controlling than the reward of a gold star?

一本书的奖励真的会比一颗金星的奖励让人感觉不那么受控制吗?

Again, I struggle to believe this.

再次,我难以相信这一点。

Instead, I think the token reward was probably more distracting than the task-related reward – which makes sense, since the task-related reward was really just a means of spending more time doing the task at hand anyway.

相反,我认为代币奖励可能比任务相关的奖励更让人分心——这也是合理的,因为任务相关的奖励实际上只是为了花更多时间完成手头任务的一种手段。

3. The largest meta-analysis on the effects of rewards and reward contingencies on intrinsic motivation

3. 关于奖励和奖励条件对内在动机影响的最大规模元分析

I was going to throw this into the previous section, but it all just got too cumbersome, so decided to save it for now.

我本来想把这个放到前面的部分,但内容实在太繁琐了,所以决定暂时留到这里。

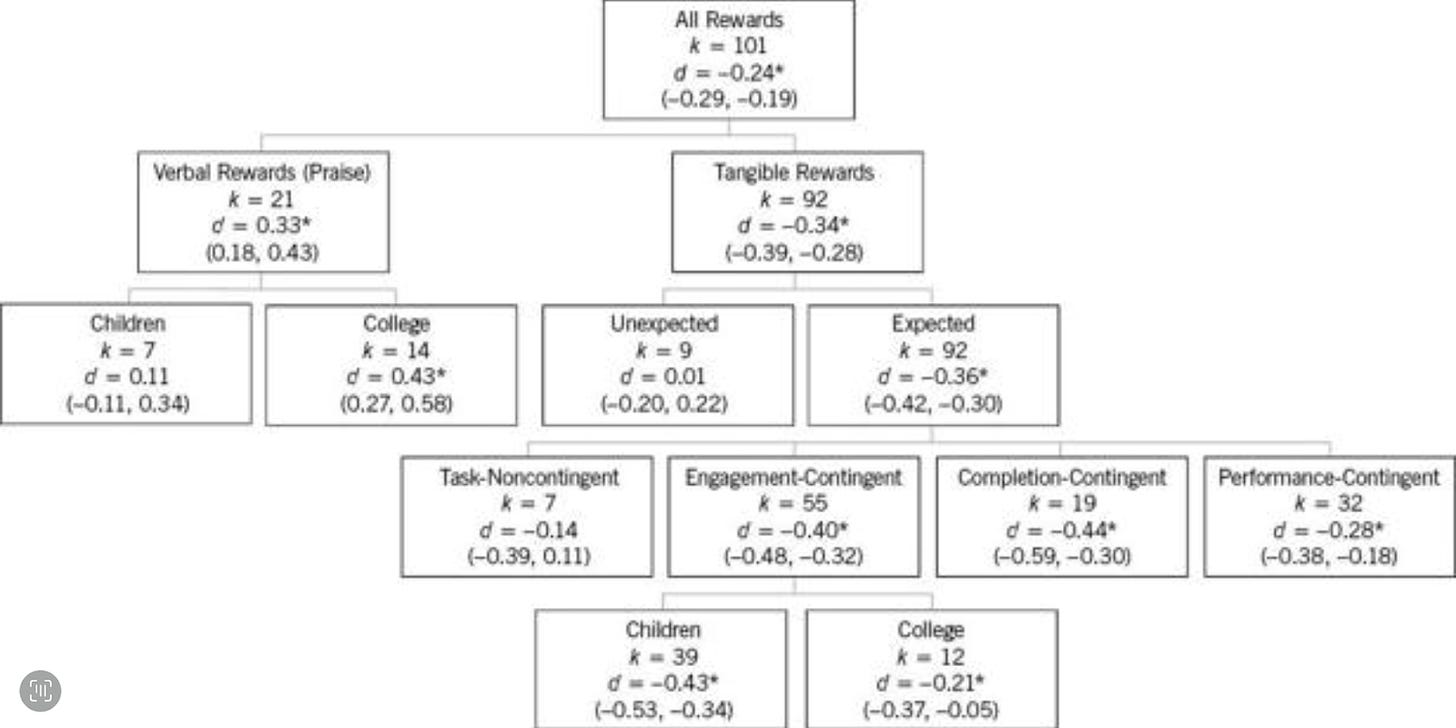

Over the years, there have been mountains of experiments looking at the effects of different rewards and reward contingencies on intrinsic motivation. In 1999, Deci et al ran a huge meta-analysis on all of this research. Here are the headline results:

多年来,有大量实验研究了不同奖励和奖励条件对内在动机的效果。1999 年,Deci 等人对所有这些研究进行了一次大规模的元分析。以下是主要结果:

(Note: k = number of individual effect sizes included in the composite effect size ; d = composite effect size. Also, the numbers in brackets at the bottom of each box are the 95% confidence interval for each composite.)

(注:k = 包含在综合效应量中的单个效应量数量;d = 综合效应量。另外,每个方框底部的括号中的数字是每个综合效应的 95%置信区间。)

Some of these categories are self-explanatory – e.g. tangible vs. verbal rewards, expected vs. unexpected rewards – but others are not. To help you interpret all of this, here’s a quick run-through of the categories I didn’t think were obvious:

这些类别中有一些是不言自明的——例如有形奖励与口头奖励,预期奖励与意外奖励——但其他类别则不然。为了帮助你理解所有这些内容,这里是我认为不明显的类别的快速概述:

Task-noncontingent rewards - rewards are given for simply being present; does not require engagement with the target activity.

任务无关奖励 - 奖励仅因出席而给予;不需要参与目标活动。Engagement-continent rewards - rewards given for spending time engaged with the target activity.

参与大陆奖励 - 因花时间参与目标活动而获得的奖励。Completion-contingent rewards - rewards given for completing a target activity.

完成条件奖励 - 因完成目标活动而给予的奖励。Performance-contingent - given for reaching a specific performance standard, e.g. doing better than 80% of people.

绩效挂钩 - 因达到特定绩效标准而给予,例如表现优于 80%的人。

Upshot: verbal rewards seem to increase intrinsic motivation; almost all tangible rewards seem to undermine it, other than unexpected tangible rewards, which don’t have much of an effect either way.

结论:口头奖励似乎能增加内在动机;几乎所有有形奖励似乎都会削弱内在动机,除了意外的有形奖励,这种奖励无论如何影响都不大。

So: 所以:

SDT - 1; Behaviourism - Nil.

SDT - 1;行为主义 - 无。

Here are a couple of bits in relation to all of this that I thought were interesting and worth drawing attention to:

以下是与这一切相关的一些有趣且值得关注的内容:

Children vs. Students – notice that for verbal praise, the effect size is way bigger for college students than for children. One quite convincing explanation for this is that that much of the praise children receive from adults in their daily lives actually is intended to control their behaviour. They are therefore much more sensitive to the controlling aspect of feedback than college students, who interpret feedback as more straightforwardly competence affirming.

儿童与学生——请注意,对于口头表扬,大学生受到的影响远大于儿童。一个相当令人信服的解释是,儿童在日常生活中从成年人那里得到的许多表扬实际上是为了控制他们的行为。因此,他们对反馈的控制性方面更为敏感,而大学生则将反馈解读为更直接的能力肯定。Praise – in addition to the findings from this meta-analysis, I thought it was worth adding that Henderlong and Lepper (2002) did a review of the praise research and found that when praise was viewed as informational, i.e. conveying genuine information about competence, it increased intrinsic motivation, whereas when praise was viewed as controlling, it harmed it.

赞扬——除了这次元分析的结果外,我认为值得补充的是,Henderlong 和 Lepper(2002)对赞扬研究进行了一次回顾,发现当赞扬被视为信息性的,即传递关于能力的真实信息时,它会增加内在动机;而当赞扬被视为控制性的时,它则会损害内在动机。Performance contingent rewards appear to have a negative impact on intrinsic motivation, but here’s the thing: a decent percentage of the experiments included in this category involved all participants receiving the reward. This means we can expect the competence affirming aspect of the reward to at least partially offset the controlling aspect. But in many real-world contexts, we would often only expect the upper X% of participants to meet the criteria for the reward. That means that the majority of people within this contingency would experience both the controlling AND the competence disconfirming aspects of the reward, which we would expect to absolutely hammer their intrinsic motivation for the activity. This whole point is interesting, because it suggests that performance contingent rewards might act as something like a gate-keeping function: anyone that performs well will receive enough competence affirming information to keep their intrinsic motivation for the activity alive. Meanwhile, everybody else’s intrinsic motivation will be completely crushed. More on this in the ‘Competition’ section below.

绩效相关的奖励似乎对内在动机有负面影响,但问题是:这一类别中包含的实验中有相当一部分是所有参与者都获得了奖励。这意味着我们可以预期奖励的胜任肯定方面至少部分抵消了控制方面。但在许多现实世界的情境中,我们通常只会期望前 X%的参与者达到获得奖励的标准。这意味着在这种情况下,大多数人会同时体验到奖励的控制方面和胜任否定方面,我们预计这将彻底摧毁他们对活动的内在动机。这整个观点很有趣,因为它表明绩效相关的奖励可能起到一种类似看门的功能:表现良好的人会获得足够的胜任肯定信息,以保持他们对活动的内在动机。而其他人的内在动机则会被完全摧毁。更多内容请参见下文的“Competition”部分。Delay time – in some of the experiments that were included in this meta-analysis, the free-choice measure was taken immediately after the reward period; in others, it was taken several days later. By comparing the two, we can get a read on whether the effects of rewards on intrinsic motivation are short-lived or whether they persist long after the rewards were administered. Turns out that the effect size for immediate and non-immediate rewards was more or less identical.

延迟时间——在本次元分析中包含的一些实验中,自由选择测量是在奖励期后立即进行的;而在其他实验中,则是在几天后进行的。通过比较两者,我们可以了解奖励对内在动机的效果是短暂的,还是在奖励给予后很长时间仍然持续。结果表明,立即奖励和非立即奖励的效果大小几乎相同。

4. Mimetic desire: a missing piece of the puzzle maybe?

4. 模仿欲望:拼图中缺失的一块吗?

When I first started writing this piece, I was planning to criticise SDT on the grounds that it doesn’t really explain why I suddenly became obsessed with school and studying rather than other things.

当我开始写这篇文章时,我原本打算批评 SDT,因为它并没有真正解释为什么我突然变得痴迷于学校和学习,而不是其他事情。

But on reflection, I actually do think it offers up a fairly plausible explanation.

但经过思考,我确实认为它提供了一个相当合理的解释。

One factor, which I’ve mentioned already, is competence: I have a knack for school and learning, and this meant that when I started working hard, I received a strong competence signal. But why did I suddenly care obsessively about going to a good university when this hadn’t been on my radar at any point prior to then?

有一个因素我已经提到过,那就是能力:我对学校和学习有天赋,这意味着当我开始努力时,我收到了强烈的能力信号。但为什么我突然开始痴迷于进入一所好大学,而在此之前这从未在我的考虑范围内?

My assumption has always been that this was a simple case of mimetic desire: all of my classmates suddenly conceived a desire to go to a good university; my desire was in some sense learned from – or an imitation of – the desire I was seeing in them.

我的假设一直是,这是一个简单的模仿欲望的案例:我所有的同学突然都产生了去一所好大学的渴望;我的欲望在某种意义上是从他们身上学来的——或者说是对他们欲望的模仿。

I think this is partially right – but one piece of the picture is missing:

我认为这部分是正确的——但还缺少了一部分内容:

Up until this point, I’d been relatively resistant to this kind of mimesis. Prior to sixth form, many of my school friends wanted nothing more than to hang out in town, chase girls, and do the usual mindless teenager stuff – but I wasn’t really interested in any of it.

到目前为止,我对这种模仿行为一直相对抗拒。在进入六年级之前,我的许多学校朋友只想在镇上闲逛,追女孩,做一些常见的无脑青少年事情——但我对这些一点也不感兴趣。

But then I enter year 12 and suddenly I become subject to the kinds of mimetic desire that I had been holding out against all this time.

但当我进入 12 年级时,突然间我开始受到那种我一直以来都在抵制的模仿欲望的影响。

What’s up with that?

这是怎么回事?

As it turns out, one of SDT’s other mini-theories – Organismic Integrations Theory (OIT) – has something quite interesting to say here.

事实证明,SDT 的另一个小型理论——有机整合理论(OIT)——在这里有一些非常有趣的观点。

In essence, OIT says that I am much more likely to internalise the values and norms of those around me when two conditions are met:

本质上,OIT 认为当满足两个条件时,我更有可能内化周围人的价值观和规范:

When my adoption of those values and norms is volitional (read: autonomous).

当我自愿(即自主地)采纳这些价值观和规范时。When I feel connected with those around me (read: relatedness).

当我感觉与周围的人有联系时(即:关联性)。

As mentioned already, when I was in sixth form, both of these conditions were met: I had a close group of friends, and my environment and relationships were much more supportive of autonomy than they had been at earlier stages of my schooling.

正如已经提到的,当我在六年级时,这两个条件都得到了满足:我有一群亲密的朋友,我的环境和人际关系比我早期学校阶段更加支持自主性。

SDT’s explanation is that this uptick in relatedness and autonomy meant that I was much more likely to internalise the values of my surroundings – those presented by my parents, teachers, and peers – and this led to far more autonomous forms of motivation becoming active.

SDT 的解释是,这种关联性和自主性的提升意味着我更有可能内化周围环境的价值观念——那些由我的父母、老师和同龄人所呈现的价值观念——这导致了更为自主的动机形式变得活跃。

5. Western centrism: the most common criticism of SDT

5. 西方中心主义:对 SDT 最常见的批评

When I was trying to understand why SDT was so rarely mentioned in mainstream circles, I did a bit of digging around the most common criticisms of the theory.

当我试图理解为什么 SDT 在主流圈子中很少被提及时,我对该理论最常见的批评做了一些挖掘。

Of those that I encountered, most weren’t particularly compelling, but one did make think: the theory – which claims to offer a universal account of human psychological needs – is excessively western-centric.

在我遇到的人中,大多数并不特别引人注目,但有一个确实让我思考:这个理论——声称提供了一个关于人类心理需求的普遍解释——过于以西方为中心。

The autonomy component of the theory seems to be the main target of this criticism: in western culture, we place a strong emphasis on autonomy as a value, but in collectivist cultures, where the needs of the individual are generally subordinated to the needs of the group, this emphasis is not there.

理论中的自主性部分似乎是这一批评的主要目标:在西方文化中,我们非常强调自主性作为一种价值,但在集体主义文化中,个人的需求通常从属于群体的需求,这种强调并不存在。

Does this mean that SDT is only applicable in the west?

这是否意味着 SDT 仅适用于西方?

Proponents of SDT generally have a couple of responses to this criticism:

SDT 的支持者通常对这一批评有几种回应:

Autonomy vs. independence – the western centricism criticism conflates the ideas of autonomy and independence. Autonomy is about acting volitionally and endorsing one’s own behaviours; independence is about being reliant upon oneself and separate from others. These are two different things. SDT is about the former – the criticism relates to the latter. It is possible to act in a highly autonomous way – that is, to endorse one’s own behaviours willingly – and to also conform to the needs of the collective. This idea is brought out in clear relief when SDT talks about morals: if I reluctantly adhere to my community’s moral rules, dragging my feet all the way, I can be said to have a low autonomy form of motivation. If I see the value in these moral laws and willingly adhere to them, I can be said to possess a high autonomy form of motivation.