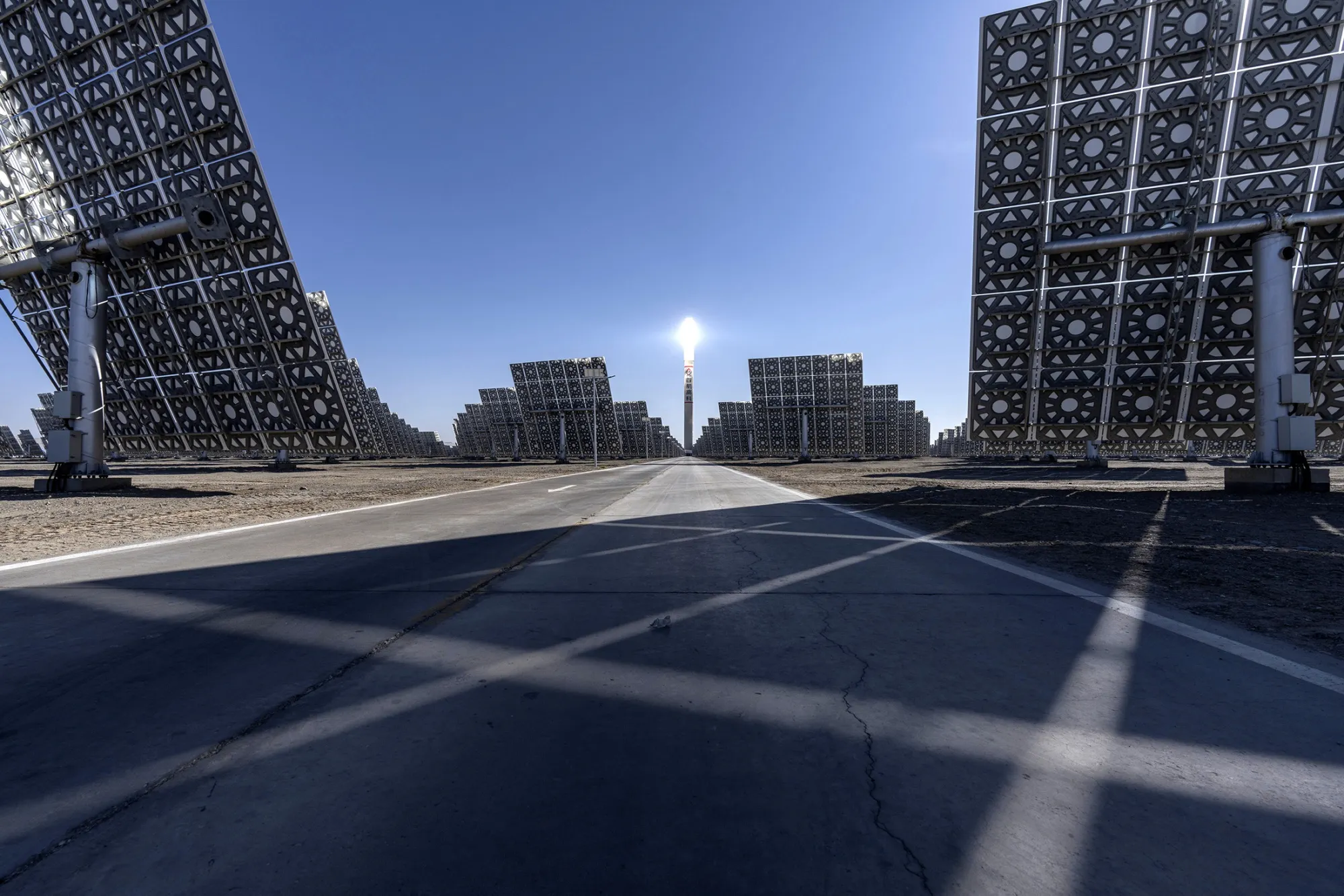

A solar thermal power station at the Dunhuang Photovoltaic Industrial Park in Dunhuang, Gansu Province, in October.

Photographer: Qilai Shen/BloombergChina Slowdown Pushes Top Polluter Towards Emissions Peak

Weaker economic growth and a surge of clean energy are combining to deliver a watershed moment in the global warming fight.

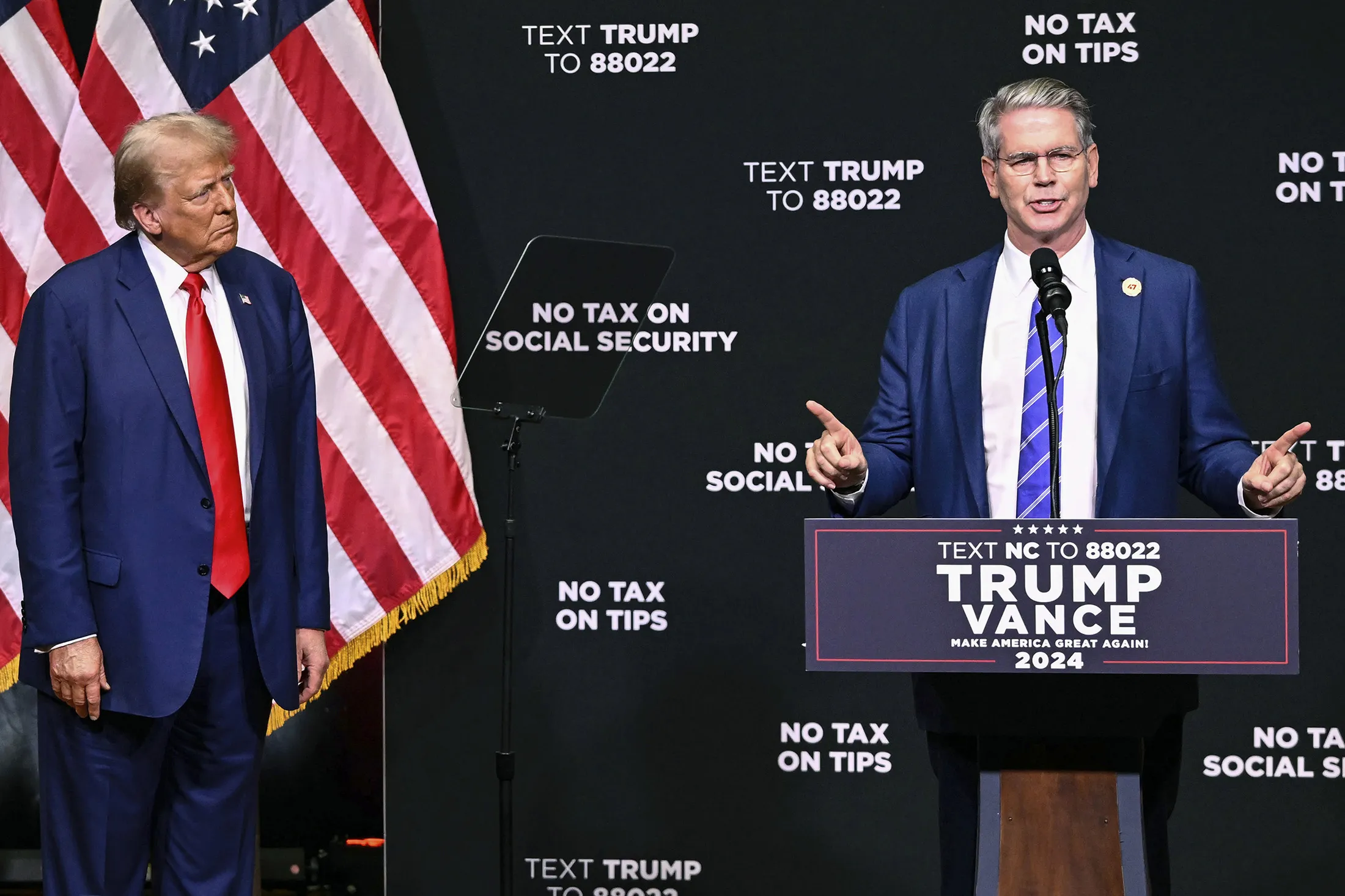

For nearly forty years, Liu Fuguo worked at the belching coal-fired power stations that helped fuel China’s astonishing economic rise. That surge also transformed the nation into the world’s largest polluter, delivering an unprecedented acceleration of greenhouse gas emissions that has steered the planet toward a calamitous climate path.

As an engineer at plants from Xinjiang to Inner Mongolia, it never crossed the 60-year-old’s mind that he might one day switch — with China — from a reliance on fossil fuels to embrace clean energy. In the northwestern Gansu desert on an October afternoon, however, Liu stood at the center of one of the most complex arrays of solar power ever constructed, in a vast, circular field of about 12,000 mirrors harnessing sunlight.

“The power industry has developed so fast,” said Liu, in a red hard hat and khaki-colored boiler suit at the industrial facility in Dunhuang, where a series of renewable energy installations generate enough electricity to power the equivalent of more than 700,000 homes. “The growth of these technologies has been unimaginable.”

China’s whirlwind economic expansion and endless appetite for polluting fuels — particularly coal — have been intertwined for decades. As annual gross domestic product, in current US dollars, jumped from about $361 billion in 1990 to around $14.7 trillion by 2020, the nation’s coal consumption quadrupled and carbon dioxide emissions more than tripled. When China surpassed Japan as the second biggest economy in 2010, it was already responsible for a quarter of global carbon pollution and has continued to expand that footprint, accounting for more than 30% of last year’s total.

The acceleration from China has been so rapid that its share of all global emissions since 1850 is already roughly equal to the 27 European Union nations combined — countries that in many cases began their industrialization at least a century earlier.

Now the factors that have propelled China’s climate-wrecking spree appear to be retreating. An unprecedented adoption of solar, wind and other clean power sources has begun to limit the country’s coal consumption. Just as importantly, a sagging economy that saw growth slow in the third quarter to the weakest pace in 18 months has cooled the most emissions-intensive corners of heavy industry like steel and cement. And President Xi Jinping’s long-term strategy is for a permanent shift from polluting sectors to cleaner, high-tech manufacturing.

That combination has put China on course for a scenario considered almost inconceivable at the start of this decade — the country’s carbon emissions may already have peaked, well ahead of Xi’s 2030 deadline.

World’s Biggest Polluter

China accounts for the largest share of carbon dioxide emissions from fossil fuels and industry

Source: Global Carbon Budget (2024)

“The power sector plays such an important role in China's emission trajectory and in China's decarbonization journey,” says Belinda Schäpe, a China policy analyst at the Centre for Research on Energy and Clean Air, or CREA, a nonprofit that tracks the nation’s pollution. “In the first half of this year, renewables have increased so much that they really pushed coal power demand into retreat — and that is the trajectory that we hope to see.”

Earlier this month, the Global Carbon Project, a coalition of climate scientists, projected that China will emit 0.2% more carbon dioxide this year than in 2023, though with a forecast range that also includes a potential decrease.

A climate milestone isn’t guaranteed. A rapid rebound in economic growth, or any government move to direct stimulus to smokestack sectors, could slow the rate of progress.

Still, a decisive shift in China away from annual increases in emissions — rather than the temporary impact of the financial crisis or the Covid pandemic — would put a global peak in carbon pollution within sight.

While China alone can’t fix the lack of progress across other nations and key industries toward climate targets, its impact would be significant. A fast decline in pollution could help make it cheaper and more achievable for the world to limit the increases in global temperatures that threaten to imperil hundreds of millions of people, devastate ecosystems and to lower economic growth. A landmark success in China might also sustain momentum in international climate action, even as the US retreats under President-elect Donald Trump’s return to office.

“The fact that we could begin to see a true slowdown and even perhaps a peak of emissions in China — that would be a very remarkable achievement,” says Pep Canadell, executive director of the Global Carbon Project.

Xi’s original declaration that China aimed to peak its emissions before 2030 and to be carbon neutral by 2060 was no less surprising. His September 2020 speech to a virtual United Nations General Assembly laying out the plans confounded other leaders, including European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen and then German Chancellor Angela Merkel who had lobbied him in the previous days to set a commitment — without any hint of his intention.

Read More: The Secret Origins of China’s 40-Year Plan to End Carbon Emissions

Even now, with evidence pointing to an emissions peak, China’s policymakers remain reluctant to discuss the prospect publicly and officials have pushed back on the idea in recent talks with Western diplomats, according to people familiar with the details.

China’s National Development and Reform Commission, the country’s top economic planner, and the Ministry of Ecology and Environment didn’t immediately respond to requests for comment sent by fax.

Acknowledging that China is on the cusp of a climate landmark would ratchet up expectations for Xi to commit to dramatically faster reductions, and to flesh out a fuller strategy to deal with potent greenhouse gasses beyond carbon dioxide, like methane and hydrofluorocarbons. China’s current 2060 net zero target is a decade later than many major economies and existing policies are ranked as “highly insufficient” by Climate Action Tracker, an independent group that grades national strategies.

Momentum in the aftermath of Xi’s 2020 announcement had initially looked weak, according to Lauri Myllyvirta, a climate analyst who spent four years living in Beijing from 2015 to better understand the shifts in China’s air pollution and emissions. A jump in electricity demand and a squeeze on fuel supplies triggered power shortages through 2021, and saw policymakers respond by lurching back to coal — sending both domestic production and imports to record levels.

In early 2023, Myllyvirta and other analysts noticed a much different trend: solar deployments had begun to rocket. By May, China had already added more new panels than throughout 2022, and at the end of that year the total was higher than the US had installed in its history. Annual solar and wind installations had more than doubled on the previous 12 months, and were larger than the rest of the world combined, according to data compiled by BloombergNEF.

By August last year, Myllyvirta hypothesized that once that deluge of clean energy was connected to the grid, it could see the country burning less fossil fuels and mean emissions would have topped out in 2023. There were caveats: the pace of renewables deployment needed to continue, and China would have to avoid any abrupt surge in energy consumption.

Emissions in China’s power sector should have begun to decline from this year, and a peak in pollution from the transport sector is also looming, BNEF said in a September report. A definitive answer will be confirmed as analysts pick through both China’s monthly economic data in January, and an annual release expected in February setting out fossil fuel consumption and emissions per unit of GDP.

The omens are good. Solar and wind deployments are on track to break last year’s records, and in July topped Xi’s 2030 target for clean power capacity. Production of steel and cement, which account for about 18% of China’s emissions, have waned as a result of the property sector’s slump.

Still, energy demand continues to grow and a heatwave in September added fresh pressure as residents cranked up air conditioners. Power generation from fossil fuels was 1.7% higher in the first half of the year on the same period of 2023, according to BNEF. Coal remains the nation’s single dominant fuel, accounting for about 60% of the power mix in 2023.

Coal Still Key in China's Energy Sector

Additions of solar and wind capacity have outpaced coal in recent years, though the fuel dominates the energy mix and accounted for 60% of electricity generation in 2023

Source: BloombergNEF

Note: Solar includes solar energy from thermal, commercial, residential and utility scale PV. Wind includes both offshore and onshore. Data shows capacity increase since 2015 and total installed capacity in 2023.

“We should not forget that China is still a developing country, pursuing modernization for a huge population,” Song Wen, head of law and institutional reform at the National Energy Administration, said at a press briefing in August. “Great efforts are still needed to achieve the goals of peak carbon and carbon neutrality.”

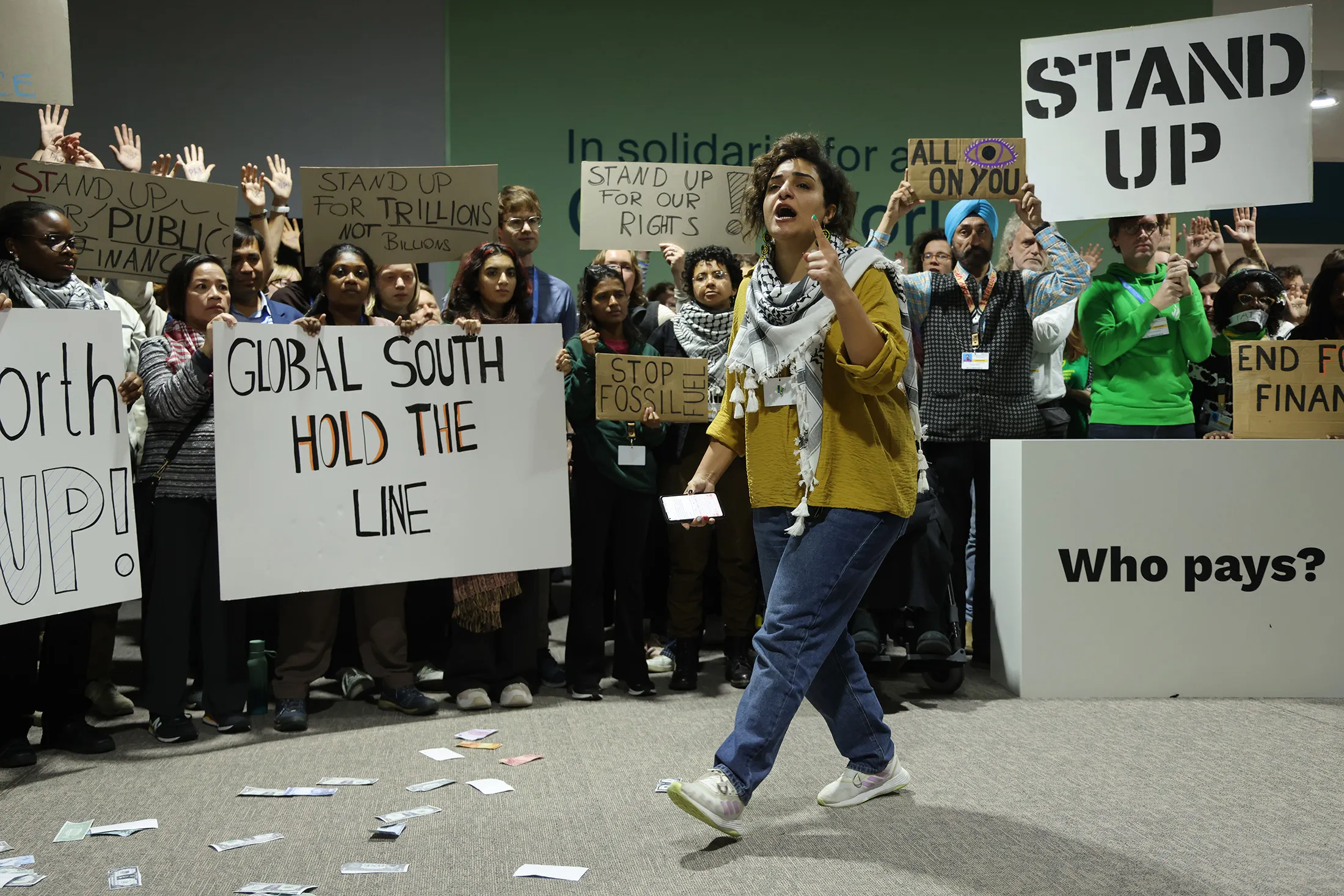

Governments globally are being pushed to increase the ambition of their emissions-cutting plans in fresh pledges for reductions by 2035 that are due to be lodged with the United Nations early next year. The EU, Canada, Mexico and other nations on Thursday used talks at the COP29 climate conference in Baku, Azerbaijan to call on large emitters to publicly commit to a faster pace of reductions, a message interpreted by many as aimed at China.

Developed nations need to “take the lead in fulfilling emission reduction obligations,” while “developing countries also need to do our best within our capabilities,” Chinese Vice Premier Ding Xuexiang said in a speech to the Baku summit, including China in the second group. The nation’s 2035 emissions plan will be “economy-wide and cover all greenhouse gases, and strive to achieve carbon neutrality before 2060,” he said.

For the rest of the world, the most crucial factor will be how quickly China cuts its annual footprint of more than 13 billion tons of carbon dioxide, rather than precisely when the total peaks. A gradual reduction — as has happened in economies like the US, Japan and the UK — won’t deliver sufficient impact. What’s needed is a sharp decline.

Historical Share of Carbon Emissions

Source: UNEP Emissions Gap Report 2024

Note: Emissions are calculated on a territorial basis. LULUCF CO2 emissions are included in historical CO2 emissions based on the bookkeeping approach. Some countries in the African Union are also included in the Least Developed Countries group

“There’s still a lot of work to do to get on track, even if emissions do stabilize,” says Helsinki-based Myllyvirta, CREA’s co-founder and a non-resident senior fellow at the Asia Society Policy Institute.

China’s recent approach to slowing growth and Xi’s broader industrial strategy indicate policy decisions are likely to be supportive, according to Michal Meidan, head of China Energy Research at the Oxford Institute for Energy Studies, and who has studied the nation’s approach for more than two decades.

Stimulus efforts haven’t been targeted at propping up heavy industry, and officials remain focused on the transition to so-called “high quality growth,” exemplified by the nation’s rising dominance in electric cars, batteries and solar panels.

Read More: Xi’s Great Economic Rewiring Is Cushioning China’s Slowdown

“They've been allowing industries that no longer serve their purpose to go through huge pain,” she says. “The outcome that China really wants is a leaner, greener industrial machine.”

About 320 kilometers (199 miles) east of Dunhaung’s solar complex, mechanical engineer Zhang Weimin manages a wind farm in Guazhou County that he says can meet power demand for about 600,000 people, and sends clean electricity as far as 2,800 kilometers away to Hunan province.

The region hosts more wind power capacity than Australia, and driving through the forest of giant turbines can take more than 30 minutes. Even with clean power deployments of that scale, he says China still needs to do more to zero out its emissions. “Our work on this is far from enough,” Zhang says.