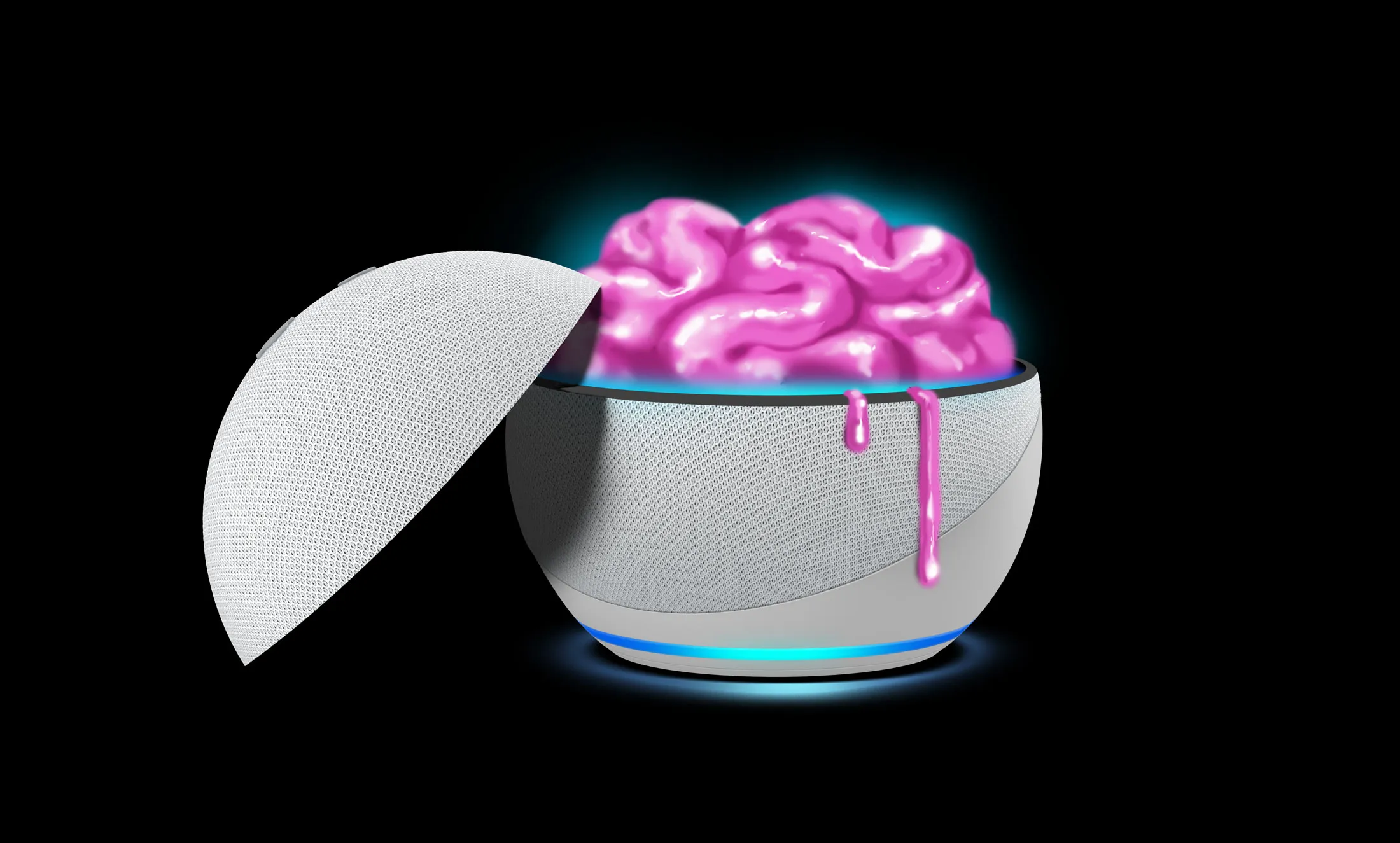

Illustration by 731; Photo: Amazon

Alexa’s New AI Brain Is Stuck in the Lab

Amazon is eager to take on ChatGPT, but technical challenges have forced the company to repeatedly postpone the updated voice assistant’s debut.

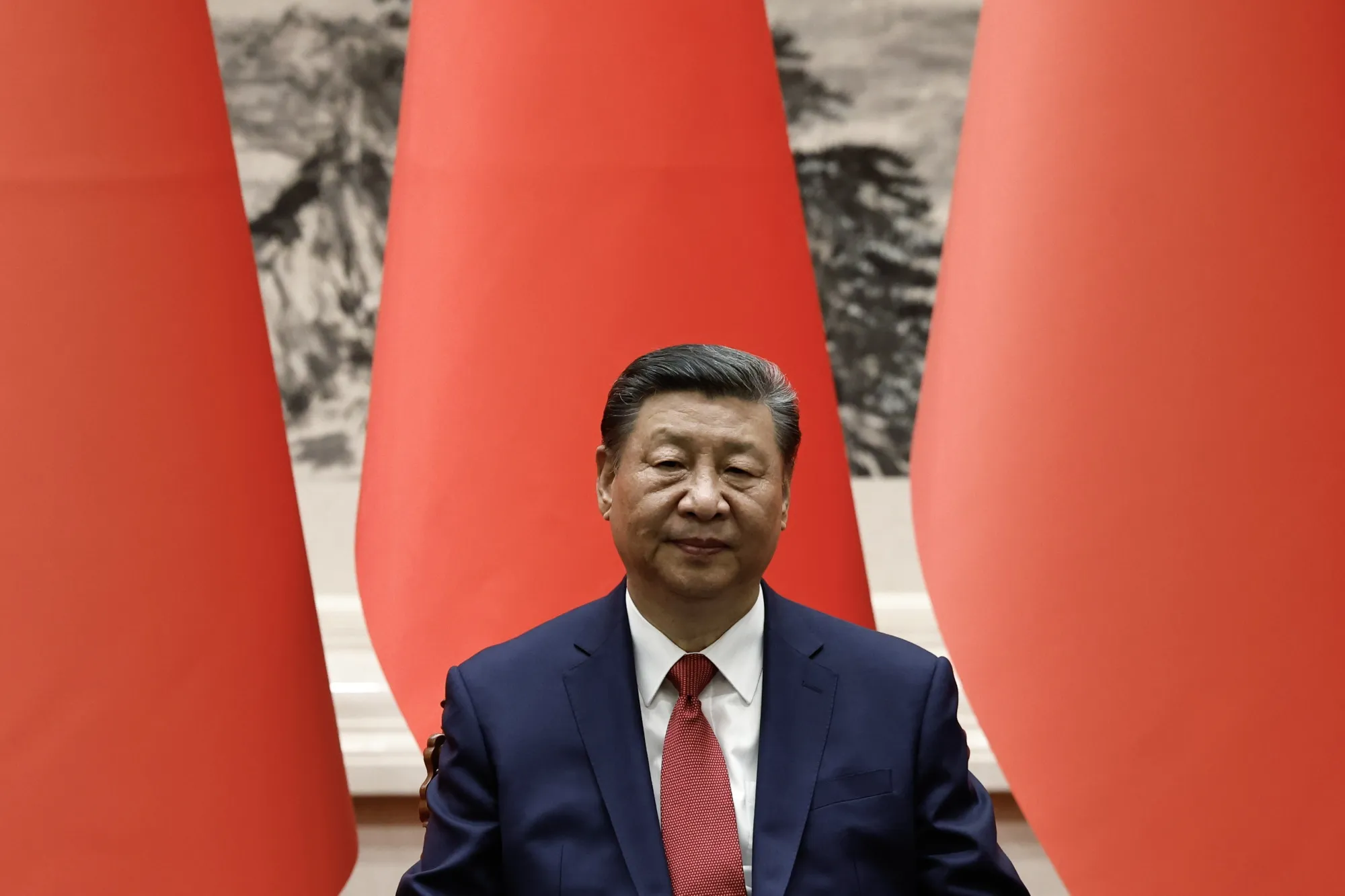

Andy Jassy kept prodding Alexa with sports questions. It was summer 2023, and Amazon.com Inc.’s chief executive officer wanted to see if a prototype of the voice assistant, upgraded with artificial intelligence, was good enough to compete with ChatGPT, the AI chatbot from OpenAI that had wowed the world around eight months earlier with its conversational wizardry.

So Jassy, a devoted New York Giants football fan and investor in the Seattle Kraken hockey team, interrogated Alexa like an ESPN reporter at a playoff press conference—asking the assistant to drill down into individual player performance, league standings, team history and so on. Alexa survived the interview, though its answers were nowhere near perfect: When Jassy asked for a recent game outcome, Alexa simply made up the score.

Still, Jassy appeared ecstatic that Amazon engineers had delivered a semi-functional demo so quickly for one of its new Echo Show devices. One person who attended the presentation recalls him saying “thank you” about 30 times. Yes, the new and improved Alexa required a lot more work. But executives were confident a beta version was doable by early 2024 and headed for wide release shortly after.

Then the timeline started slipping. At one point, the company aimed to unveil the finished product at a splashy event with Jassy on Oct. 17, according to internal documents reviewed by Bloomberg. Amazon scrapped that plan, instead holding a smaller launch party showcasing new versions of its Kindle e-readers. A person familiar with the matter said Alexa AI teams were recently told that their target deadline had been moved into 2025.

Amazon, which declined to make executives available for interviews, said its vision remains to build Alexa into the world’s best personal assistant, and that generative AI represents a huge opportunity to improve the service. “We have already integrated generative AI into different components of Alexa, and are working hard on implementation at scale—in the over half a billion Alexa-enabled devices already in homes around the world—to enable even more proactive, personal, and trusted assistance for our customers,” spokesperson Kristy Schmidt said in an emailed statement.

Alexa’s conversational abilities have improved since the Jassy demo, but top engineers and testers involved with the effort say the AI-enhanced assistant can still drone on with irrelevant or superfluous information and struggles with humdrum tasks it previously excelled at, like turning on and off the lights.

That Amazon finds itself in this position is objectively astounding. A decade ago, Alexa defined the novel category of listening hardware—smart speakers, televisions, tablets, cameras, car accessories, microwaves—that could quickly respond to verbal requests.

It’s true that Alexa is little more than a glorified kitchen timer for many people. It hasn’t become the money maker Amazon anticipated, despite the company once estimating that more than a quarter of US households own at least one Alexa-enabled device. But if Amazon can capitalize on that reach and convince even a fraction of its customers to pay for a souped-up AlexaGPT, the floundering unit could finally turn a profit and secure its future at an institutionally frugal company. If Amazon fails to meet the challenge, Alexa may go down as one of the biggest upsets in the history of consumer electronics, on par with Microsoft’s smartphone whiff.

Some employees blame Alexa’s woes on bureaucracy and management bloat that Jassy has been trying to extinguish. (In a Sept. 16 company-wide memo, he criticized unnecessary “pre-meetings for the pre-meetings for the decision meetings.”) Other insiders speak of deeper problems with the Amazon playbook that has historically thrived on sustaining early leads, such as with Prime, Kindle and the Amazon Web Services juggernaut that Jassy ran for 18 years before succeeding Jeff Bezos as CEO in 2021. The company is also known to mount swift comebacks, outmaneuvering eBay Inc. with its own marketplace for independent sellers or taking on Netflix Inc. in streaming video. Even Alexa only won by hurdling Apple Inc.’s Siri.

What’s different this time, current and former staffers say, is that Jassy has yet to convey a compelling vision for an AI-powered Alexa. Many of these people say the project still needs tons of fixes and that they’re not bullish that the resulting product will compare favorably with the long list of AI apps already out in the market. Without its usual first- or second-mover advantage, Amazon’s best hope is that it can ship the 13th or so permutation of ChatGPT. A former senior engineer who helped improve the AI for the company’s e-commerce engine says Amazonians believed they were building a 1,000-year company during the Bezos era. Now, this engineer says, it feels like Amazon is playing catch-up.

Alexa was born of a blue-sky ask from Bezos “to build a $20 device with its brains in the cloud that's completely controlled by your voice.” Written in an email to his product leaders in 2011, the same year Apple introduced Siri, the request sent researchers on a strange, three-year journey to figure out how to acoustically detect a specific keyword (e.g., “Alexa”) that would activate the machine, identify speech patterns and reply accordingly.

Bezos pitched Alexa to shareholders as an “AI assistant,” though it wasn’t quite “AI,” at least not in the current sense of the term. Whereas state-of-the-art AI services like ChatGPT, Microsoft’s Copilots and Google’s Gemini are capable of vast interpretation and generating endlessly unique responses, Alexa was initially built in part on a rules-based system that logically mapped answers to contextually similar questions. It couldn’t write an essay on the fly or analyze a thorny calculus problem. But whether users asked what it’s like outside, if rain was expected or they needed an umbrella, Alexa understood they likely wanted the day’s forecast.

This type of approach was core to upping Alexa’s IQ. Because its knowledge structures were stored on internet servers, Amazon could keep feeding it new datasets and Q&A templates. Training the virtual assistant originally involved hiring paid actors to recite lines into test speakers and scripting out answers.

The resulting $180 Amazon Echo, a black cylindrical gadget about as tall as a canister of tennis balls, was unveiled in late 2014 to furrowed reactions. Reviewers hadn’t seen anything like it. Yet Alexa was an immediate hit, in part because of its instant accessibility: While Siri required an iPhone and a button-press to use, Alexa offered hands-free assistance in a standalone device intended for the living room.

Soon, Echo sales surpassed a million units, and Amazon’s devices division, which oversaw Alexa’s software, was planning tons of low-cost alternatives. The famously parsimonious Bezos was so bullish that he blessed the division, which boasted 1,000 employees by 2016, with significant resources and autonomy. An ex-hiring manager says recruiters were encouraged to tell engineers offered jobs in another part of Amazon that they should join the Alexa group instead. “Nobody else was building these,” Dave Limp, then Amazon’s devices head, told Bloomberg News last year. “Google hadn’t shipped anything yet. Apple wasn’t in the business.”

The consumer experience was so unfamiliar that Amazon included quirky instructions on how to interact with Alexa. It recommended, for example, users ask Alexa to play music, read the news—and even define “the meaning of life.” Of course, Alexa couldn’t actually wax philosophical about the latter query, meant in jest, but engineers could program it with a series of funny reactions that imbued it with personality. Amazon says Alexa is based on an intent-prediction system that uses a combination of deep learning and automated language processing to improve the service.

Maintaining and maturing Alexa’s call-and-response repository was astonishingly labor-intensive. To improve Alexa’s speech recognition, Amazon hired an army of workers to transcribe audio recordings of misunderstood “utterances” and manually teach Alexa what was actually being said. Meanwhile, the machine-learning group, led by a staid scientist named Rohit Prasad who had worked at labs in Boston and Cambridge, Massachusetts, continued expanding to what they called new “domains,” so Alexa could summon real-time sports scores or search for a TV show on a set-top box.

In the ensuing years, Limp, in a rush to own any corner of the voice market, injected Alexa into an anything-goes taxonomy of mostly cheap hardware. Tiny speakers for bedside tables. Voice-enabled light bulbs and clocks and ovens. During Prime sales, some Echos sold for as little as $14.99. In 2019, Limp even announced eyeglasses and finger rings with mics for talking with Alexa on the go. Although these doohickies were frequently sold at cost or a loss, a pliable metric called “Downstream Impact,” or DSI, justified the expense. The more Alexa devices that a customer purchased, the more that customer’s DSI was projected to rise in the future, from increased shopping revenue (“Alexa, order more paper towels”) or Prime add-ons to subscriptions like music streaming and home-security services. That at least was the hope.

The spaghetti-on-the-wall hardware strategy found traction, helping Amazon sell north of 100 million Alexa devices. It also created a mess for various teams of software engineers, who were incessantly derailed from longer-term product roadmaps to craft custom concierge features and answer templates for the eclectic array of devices, three people with knowledge of the dynamic say. Worse, Alexa’s rigid thinking required annoying manual configurations in its companion app and stilted voice instructions for cooler queries that Amazon marketed in Super Bowl commercials, such as phoning a friend directly from an Echo.

Alexa Everywhere

Amazon put the voice assistant in everything from microwave ovens to clocks

Source: Data compiled from product announcements and listings from Amazon and its brand subsidiaries. Photos: Amazon

While Prasad’s group did build tools to automate Alexa’s learnings, they took a lot of fine-tuning among increasingly compartmentalized units. One mined answers from a Wikipedia-style “knowledge graph” Amazon had acquired a few years earlier from a startup specializing in aggregating public data. Another focused on outsourced answers from the web, and on and on for more specific domains. Alexa’s “brains” were essentially carved up cerebra splattered across far-flung Amazon labs around the world. The siloed work was reflected in Alexa’s responses: Four people familiar with the back-end process say each time a question is asked, Alexa generates a bunch of different competing answers, and within a split second, conveys just one driven by an internal score of which is likely the most relevant.

Financial resources and headcounts were partly dictated by which parts of these brains—and the teams that developed them—provided higher percentages of answers, a survival-of-the-fittest contest. One former Alexa executive says some units would intensely track domain-traffic figures weekly to make sure theirs wasn’t falling behind rivals and risking elimination. The scramble for resources generated chaos, this person says, prompting intense competition in a culture already known for sharp elbows. It’s unclear if this setup benefited customers or just victorious product fiefdoms. Amazon says it invests in areas that provide the most customer benefit and that its teams don’t compete in this manner. The company also says it considers much more than domain-response volumes when allocating resources.

By 2020, Alexa brass began to question the accuracy of Alexa’s DSI metrics, which had not turned the software into the profitable business promised on paper. Despite the division boasting some 10,000 employees, the gadgets were still sold at a price that only enabled Amazon to break even, and attempts to generate digital revenue had flopped. Alexa’s interactions were just too clunky for more advanced apps. Even as it added support for third-party developers, and users could download “skills” for bespoke voice experiences (yoga classes, cooking recipes, Jeopardy! trivia, etc.), most were gimmicky and available for free.

Amazon’s own revenue efforts flunked too. One of Alexa’s core promises—that it would encourage consumers to shop with their voice—never caught on. The company has said that more than half of Echo users have used the devices to shop, but Alexa veterans warn that such stats include steps like making a shopping list. Employees say scrutiny of DSI intensified as the world reopened after the Covid-19 pandemic and Amazon’s sales growth slowed once shoppers returned to stores. Jassy combed through the financial health of the devices business and squinted at Alexa’s metrics, according to two people familiar with the matter. Even isolated from larger tailwinds impacting Amazon’s other businesses, they were hugely disappointing. (The Wall Street Journal reported on Jassy’s fiscal review earlier this year. Amazon says the opportunity ahead for Alexa is greater than what now appears on any balance sheet, and that Jassy believes in the long-term business potential and ingenuity of his teams.) Things needed to change.

On Nov. 30, 2022, ChatGPT upended the game. OpenAI’s chatbot used large language models—systems fed massive amounts of data, including books, articles and online comments—to spit out the best possible responses to users’ queries. The new architecture was radically different, and smarter, than Alexa’s, with stunning conversational abilities and creative problem-solving. It could handle natural dialogue and actually wax philosophical about the meaning of life without preloaded responses. Suddenly, Amazon felt years behind on AI assistants.

Tellingly, OpenAI’s release didn’t spark a “code red” moment like it did at Google, where execs immediately marshaled troops to focus on generative AI, recognizing the existential threat to its flagship search engine. If anything, Amazon insiders say there was instead huge excitement about what this AI leap could mean for the Alexa business. Two weeks earlier, though, Amazon had announced thousands of layoffs, many targeting the unprofitable Devices and Services division. Jassy told employees he was freezing new hiring in the face of economic uncertainty. They’d have to do more with less.

Then ChatGPT went viral—hitting 100 million active users within months—and OpenAI introduced a premium subscription, in February 2023, for $20 a month. A major Alexa upgrade became more urgent inside Amazon. It wasn’t the first time Amazon attempted to develop a dialogue simulator. In 2020, the company had launched a feature called “Alexa Conversations” so it could chitchat about, say, movie recs instead of merely providing data scraped from subsidiary IMDB.com. But it was still undergirded by templates and a library of possible answers.

Amazon says it began incorporating early LLMs into Alexa around this time, including one called “Alexa Teacher Model” deployed in 2021 to enhance its learning capabilities. Engineers had also been experimenting with layering relatively primitive models atop Alexa’s existing databases, searching for a way to make the assistant more conversant. But that effort wasn’t a priority, according to three people familiar with the development, and many throughout the rest of the Alexa group weren’t even aware of the tinkering. A former Alexa product leader says they never once heard anybody talk about large language models until after ChatGPT debuted.

As Amazon set about developing a comparable LLM, determining how to migrate Alexa’s brains to this framework was a migraine. Some employees quip that Alexa had more in common with an automated phone tree than AI. Shifting to pretrained AI models meant Alexa could handle infinitely more complex questions on its own but risked becoming less reliable for basic tasks, such as setting kitchen timers or fishing a one-off answer from a plugged-in database. For example, when Jassy tested the Alexa AI prototype that summer of 2023, it wasn’t able to deliver accurate football scores on the spot because it was tapped into a generic language model, not real-time sports info. Other teams building AI demos for Jassy experimented with Meta Platforms Inc.’s Llama models, which were more advanced than Amazon’s.

Prasad’s team was split from Limp’s devices division, so it reported directly to Jassy and was no longer beholden to the hardware strategy. (Limp has since left to head up Bezos’s Blue Origin space venture.) The Alexa group was given a broad remit to build foundational models that could be used by other Amazon teams, as well as resold by the cloud division. The scale of the ambition was made clear by the group’s new name: Artificial General Intelligence.

Their work was unveiled during a September 2023 product event at Amazon’s massive new office complex in Arlington, Virginia. A live conversation, using the same Echo Show model Jassy had privately tested, demonstrated how Alexa could chat lithely about the Seahawks’s performance, its next game, recommend a BBQ menu and craft an invitation to send to friends. “It feels just like talking to a human being,” a confident Prasad said on stage. To gain access to this new mode before it rolled out to the general public, users would have to tell Alexa “let’s chat,” and it would eventually notify them when the experience was available.

Media reaction was positive, but inside Amazon it was becoming increasingly clear that an early 2024 rollout was unlikely. Alexa’s response times could be sluggish and it was having trouble with AI hallucinations. Two people involved with the project say satisfaction scores with beta users were low–responses sounded stiff and were not all that useful—and that Alexa now messed up some smart-home integrations. The new AI architecture sometimes overthought queries, too, irritating listeners. The former Alexa executive says it was akin to asking for the day’s temperature and the AI responding “81.0583°.”

Prasad, normally a buttoned-up and methodical presence, was showing signs of strain in weekly progress meetings. A long-time collaborator says the priority moved from judicious discussions about a cohesive vision for Alexa’s future to pressuring his lieutenants to implement new AI functionality ASAP. This person said they had never seen Prasad so stressed and said the guidance was often to “just ship it.” Amazon says the Alexa team has pioneered groundbreaking advances in speech and language technologies under Prasad and that he’s the right leader to deliver on the company’s AI vision.

In recent months, internal testers of Alexa’s AI have found it nowhere as good as ChatGPT. These people still review transcripts to improve Alexa, though their training is now multifaceted. Instead of simple call-and-response scripts, they’re now reviewing several layers of Alexa’s intuition, checking for its observations about a question and thoughts for how to respond, in addition to the quality of its answers. Dialogue data is tracked in spreadsheets.

Technically, it’s smarter, but not necessarily wiser. One tester says the ongoing hallucinations aren’t always wrong, just uncalled for, as if Alexa is trying to show off its newfound prowess. For instance, before, if you asked Alexa what halftime show Justin Timberlake and Janet Jackson performed at, it might say the 2004 Super Bowl. Now, it’s just as likely to give a long-winded addendum about the infamous wardrobe malfunction.

Another testing expert said some of the proposed queries—such as asking Alexa to help with a cover letter or debug computer code—were utterly unsuited to a voice assistant. Such queries would require a keyboard and screen, not a hands-free Echo. The expert guessed these requests were likely coming from an app-based version of Alexa that could be asked typed questions, not just verbal ones. Regardless, this tester was instructed to keep replies to 30 seconds or less so as not to frustrate users. The result was like grading bad papers, this person says.

In some ways, Alexa’s biggest chance of catching up to ChatGPT—the millions of devices in consumers’ hands—is also its greatest liability. Users toying with ChatGPT expect it to make mistakes. If Amazon turned on its LLM brains and Alexa began spewing provocative answers, it could turn into a fiasco for Jassy given the huge portion of kids and families that use Echo hardware.

While Amazon has been developing its LLMs, a former AI engineer says Alexa teams have lately been leaning on models from France’s Mistral AI and San Francisco-based startup Anthropic, in which Amazon has invested $4 billion. (Amazon says no single model works best for every use case and that its teams take advantage of multiple LLMs available through AWS.) Jassy also poached Microsoft Corp. product chief Panos Panay, who spearheaded the software maker’s Windows hardware and Surface laptop lineup, to take over Amazon’s devices group. He’s brought a focus on higher-quality designs to a group adept at utilitarian gadgets, according to two people familiar with his plans.

Even as Jassy pushes Amazon’s engineers to quickly infuse generative AI into more products, he’s said—both internally and externally—that the technology is in its early phases. The competitive landscape is still shaking out. Executives in Seattle have watched as early efforts to combine LLM-powered assistants with personal devices, including by Humane Inc. and Rabbit Inc., have flopped. Apple, which like Amazon isn’t viewed as a leader in consumer AI, has only recently begun infusing elements of the technology into its iOS mobile platform. An AI-updated version of Siri won’t likely arrive until next year. The iPhone isn’t going anywhere in the meantime, even if sales of its new edition are softer this holiday season.

But Amazon’s leaders, who grasp how quickly people may unplug an Echo if something superior comes along, realize they’ve got perhaps one shot to reintroduce Alexa to the world, according to three people close to the company. So they’re holding fire. For the first time since 2017, the month of September, normally reserved for new Alexa announcements, came and went without a big reveal. Instead, Panay hosted a press event the following month, when he talked up Amazon’s updated slate of Kindles.

Meanwhile, consumers who requested the “let’s chat” feature Amazon touted last fall are still waiting to converse with the new Alexa AI on their Echos. The company has since stopped inviting those who opt in to the upgrade, and is instead recommending they stick with the basics. “You can ask me questions or to do things like set at timer, play music, turn on a connected light and more,” Alexa now responds when asked to chat.