Dough makes bread and dough makes deals

面团做面包,面团做交易

Some people would argue that deals, not movies, are Hollywood’s major product. “Contract-driven” is a handy way to describe the business.

有些人会说,交易,而不是电影,是好莱坞的主要产品。“合同驱动”是一个方便的方式来描述业务。

Although studios are often viewed as being monolithic enterprises, they actually function broadly as venture capitalists and intellectual property clearinghouses simultaneously engaged in four distinct business functions: financing, producing, distributing, and marketing and advertising movies.1 Each function requires the application of highly specialized skills that include raising and investing money, assessing and insuring production costs and risks, and planning and executing marketing and advertising campaigns. And every motion picture and television project must inevitably confront and then cope with three main risks, first in financing, then in completion, and then in performance. This chapter describes the framework in which these functions are performed.

虽然电影公司通常被视为单一的企业,但它们实际上是风险资本家和知识产权清算所,同时从事四种不同的业务职能:融资,制作,发行,营销和广告电影。1每项职能都需要运用高度专业化的技能,包括筹集和投资资金、评估和确保生产成本和风险、规划和执行营销和广告活动。每一个电影和电视项目都不可避免地要面对并科普三个主要风险,首先是融资风险,然后是完工风险,最后是业绩风险。本章介绍了履行这些职能的框架。

4.1 Properties – Tangible and Intangible

4.1属性-有形和无形

Stories and narratives form the bedrock of all entertainment because they stimulate and engage the human brain. They are, some would posit, universal across cultures and societies, and are unique to our species.

故事和叙事构成了所有娱乐的基石,因为它们刺激和吸引了人类的大脑。有些人会说,它们是跨文化和社会的普遍现象,是我们这个物种所独有的。

A movie screenplay begins with a story concept based on a literary property already in existence, a new idea, or a true event. It then normally proceeds in stages from outline to treatment, to draft, and finally to polished form.2

电影剧本以一个故事概念开始,这个故事概念是基于一个已经存在的文学性质、一个新的想法或一个真实的事件。然后,它通常进行阶段,从大纲到处理,草案,最后到抛光的形式。2

Prior to the outline, however, enters the literary agent, who is familiar with the latest novels and writers and always primed to make a deal on the client’s behalf. Unsolicited manuscripts normally make little or no progress when submitted directly to studio editorial departments. But with an introduction from an experienced agent – who must have a refined sense of the possibility of success for the client’s work and of the ever-shifting attitudes of potential producers – a property can be submitted for review by independent and/or studio-affiliated producers. Expenditures at this stage usually involve only telephone calls and some travel, reading, and writing time.

然而,在大纲之前,文学经纪人会介入,他熟悉最新的小说和作家,并且总是准备好代表客户达成交易。未经请求的手稿通常很少或根本没有进展时,直接提交给工作室编辑部。但是,如果有经验丰富的经纪人介绍--他必须对客户的作品成功的可能性以及潜在制作人不断变化的态度有敏锐的认识--一处房产可以提交给独立和/或工作室附属制作人进行审查。这一阶段的支出通常只包括电话费和一些旅行、阅读和写作时间。

However, should the property attract the interest of a potential producer (or perhaps someone capable of influencing a potential producer), an option agreement will ordinarily be signed. Just as in the stock or real estate markets, such options provide, for a small fraction of the total underlying value, the right (but not the obligation) to purchase the property in full. Options have fixed expiration dates and negotiated prices, and depending on the fine print, they can sometimes be resold. Literary agents, moreover, usually begin to collect at least 10% of the proceeds at this point.

然而,如果该财产吸引了潜在生产者的兴趣(或者可能是能够影响潜在生产者的人),通常会签署一份期权协议。就像在股票或真实的房地产市场一样,这些期权提供了购买全部财产的权利(但不是义务),只需要总潜在价值的一小部分。期权有固定的到期日和商定的价格,根据细则,它们有时可以转售。此外,文学代理人通常开始收集至少10%的收益在这一点上。

Now, in the unlikely event that a film producer decides to adapt one of the many properties offered, the real fund-raising effort begins. This effort is legalistically based on what is known as a literary property agreement (LPA), a contract describing the conveyance of various rights by the author and/or other rights-owners to the producer. To a great extent, the depth and complexity of the LPA will be shaped by the type of financing available to the producer of this project.

现在,万一电影制片人决定改编所提供的众多房产中的一处,那么真实的筹款工作就会开始。这一努力在法律上基于所谓的文学财产协议(LPA),这是一份描述作者和/或其他权利所有者向制作人转让各种权利的合同。在很大程度上,LPA的深度和复杂性将取决于该项目生产者可获得的融资类型。

For example, if the producer is affiliated with a major studio, the studio will normally (in the LPA) insist on retaining a broad array of rights so that a project can be fully exploited in terms of its potential for sequels, television series spin-offs, merchandising, and other opportunities. Such an affiliation will often significantly diminish, if not totally relieve, the producers’ financing problems because a studio distribution contract can be used to secure bank loans. Better yet, a studio may also invest its own capital. But more commonly, “independent” producers will have to obtain the initial financing from other sources – which means that they are thus not fully independent. In pursuit of such start-up capital, many innovative financing structures have been devised.

例如,如果制片人隶属于一家大型工作室,该工作室通常会(在LPA中)坚持保留广泛的权利,以便项目可以充分利用其续集,电视连续剧衍生产品,商品销售和其他机会的潜力。这种联系即使不能完全缓解制片人的融资问题,也往往会大大减少,因为制片厂发行合同可以用来获得银行贷款。更好的是,工作室也可以投资自己的资金。但更常见的情况是,“独立”生产者将不得不从其他来源获得初始资金-这意味着它们并非完全独立。为了寻求这种启动资金,设计了许多创新的融资结构。

Even so, funding decisions are normally highly subjective, and mistakes are often made: Promising projects are rejected or aborted, and whimsical ones accepted (i.e., “green-lighted” in industry jargon). The highly successful features Star Wars and Raiders of the Lost Ark were shopped around to several studios before Twentieth Century Fox and Paramount, respectively, agreed to finance and distribute them. Jaws was, moreover, nearly canceled midway in production because of heavy cost overruns, Home Alone was placed in turnaround well after its preparation had started, and the script for Back to the Future was initially rejected by every studio.3

即便如此,资助决策通常是高度主观的,而且经常会犯错误:有前途的项目被拒绝或放弃,异想天开的项目被接受(即,用行业术语来说是“绿灯”)。非常成功的《星星大战》和《夺宝奇兵》在二十世纪福克斯和派拉蒙分别同意资助和发行之前被几家电影公司购买。此外,《大白鲨》由于严重的成本超支而几乎在制作中途被取消,《小鬼当家》在筹备工作开始后很久就被置于周转期,《回到未来》的剧本最初被每个工作室拒绝。3

Of course, for funding to be obtained, a project must already be outlined in terms of story line, director, producer, location, cast, and estimated budget. To reach this point, enter the talent agents who play an important role in obtaining work for their clients, sometimes by assembling into “packages” the diverse but hopefully compatible human elements (and, more recently, the financings) that go into the making of feature films or television programs.4

当然,要获得资金,一个项目必须已经在故事线,导演,制片人,地点,演员和预算方面概述。为了达到这一点,我们来看看在为客户争取工作方面发挥重要作用的人才经纪人,他们有时会把各种各样但希望相互兼容的人力资源(以及最近的融资)组装成“包装”,用于制作故事片或电视节目。4

The largest multidivision talent agencies are the Creative Artists Agency (CAA), which became a Hollywood powerhouse in the 1980s, William Morris Endeavor, United Talent Agency, International Creative Management (ICM), and United Talent Agency.5 In addition, there are also smaller and highly specialized firms, among which are “discount” agencies that place talent for fees of less than the standard 10% of income.

最大的多部门人才机构是创意艺术家机构(CAA),它在20世纪80年代成为好莱坞的发电站,威廉莫里斯奋进,联合人才机构,国际创意管理(ICM)和联合人才机构。[5]此外,还有一些规模较小、高度专业化的公司,其中包括“折扣”机构,这些机构以低于收入10%的标准费用雇用人才。

Agents, in the aggregate, perform a vital function by generally lowering the cost of searching for key components of a film project and by relaying and replenishing the constant and necessary industry database known as gossip. As such, gossip is a natural offshoot of an agent’s primary purpose, which is to advance the careers of clients at whatever price the talent market will bear. The use of agents also permits talent employers to confine their work relations to artistic matters and to delegate business topics to expert handling by the artists’ representatives.

总的来说,代理商通过降低寻找电影项目关键组成部分的成本,以及通过中继和补充被称为八卦的恒定和必要的行业数据库,发挥着至关重要的作用。因此,八卦是经纪人主要目的的一个自然分支,其主要目的是以人才市场能够承受的任何价格促进客户的职业发展。使用代理人还使人才雇主能够将其工作关系限于艺术事务,并将商业问题委托给艺术家代表的专家处理。

4.2 Financial Foundations

4.2财务基础

Some of the most creative work in the entire movie industry is reflected not on the screen but in the financial offering prospectuses that are circulated in attempts to fund film projects. On the financing front especially, studios also always face a risk-inducing cash flow timing condition in that outflows of funds for production and marketing are largely concentrated over the short run, while inflows from sales and licensing in various markets are dispersed over the long run. Financing for films can be arranged in many different ways, including the formation of limited partnerships and the direct sale of common stock to the public. However, financing sources fall generally into three distinct classes:

在整个电影行业中,一些最具创造性的作品并没有反映在银幕上,而是反映在为电影项目融资而发行的招股说明书中。特别是在融资方面,电影公司也总是面临着一个引发风险的现金流时间条件,因为用于生产和营销的资金流出主要集中在短期内,而来自各个市场的销售和许可的流入则分散在长期内。电影的融资可以通过许多不同的方式安排,包括成立有限合伙企业和向公众直接销售普通股。然而,资金来源一般分为三类:

1. Industry sources, which include studio development and in-house production deals and financing by independent distributors, talent agencies, laboratories, completion funds, and other end users such as television networks, pay cable, and home video distributors

1. 行业来源,其中包括工作室开发和内部制作交易以及独立分销商,人才中介,实验室,完成基金和其他最终用户(如电视网络,付费有线电视和家庭视频分销商)的融资2. Lenders, including banks, insurance companies, and distributors

2. 贷款人,包括银行、保险公司和分销商3. Investors, including public and private funding pools arranged in a variety of organizational patterns.

3. 投资者,包括以各种组织模式安排的公共和私人资金池。

The most common financing variations available from investors and lenders are discussed in the following section. Industry sources are discussed in Chapter 5.

下一节讨论投资者和贷款人提供的最常见的融资方式。第5章讨论了行业来源。

Common-Stock Offerings 普通股股票

Common-stock offerings are structurally the simplest of all to understand. A producer hopes to raise large amounts of capital by selling a relatively small percentage of equity interest in potential profits. But as historical experience has shown, offerings based on common stock do not, on average, stand out as a particularly easy method of raising production money for movies. Unless speculative fervor in the stock market is running high, movie-company start-ups usually encounter a long, torturous, and expensive obstacle course.

普通股发行在结构上是最容易理解的。生产商希望通过出售潜在利润中相对较小比例的股权来筹集大量资金。但历史经验表明,一般来说,发行普通股并不是一种特别容易的电影制作资金筹集方法。除非股票市场的投机热情高涨,否则电影公司的初创企业通常会遇到漫长、痛苦和昂贵的障碍。

The main difficulty is that a return on investment from pictures produced with seed money may take years to materialize, if it ever does, and underlying assets initially have little or no worth. Hope that substantial values will be created in the not too distant future is usually the principal ingredient in these offerings. In contrast to boring but safe investments in Treasury bills and money-market funds, new movie-company issues promise excitement, glamour, and risk.6

主要的困难在于,用种子资金制作的电影的投资回报可能需要数年时间才能实现,如果真的实现的话,而基础资产最初几乎没有价值。希望在不久的将来创造大量价值通常是这些产品的主要成分。与枯燥但安全的国库券和货币市场基金投资不同,电影公司发行的新债券充满了刺激、魅力和风险。6

Straight common-stock offerings of unknown new companies are thus generally difficult to launch in all but the frothiest of speculative market environments.7 Strictly from the stock market investor’s viewpoint, experience has shown that most of the small initial common-stock movie offerings have provided at least as many investment nightmares as they have tangible returns.

因此,在泡沫最大的投机市场环境下,不知名的新公司的普通股发行通常很难推出。[7]严格从股票市场投资者的角度来看,经验表明,大多数小型的首次发行普通股电影提供的投资噩梦至少与它们的有形回报一样多。

A rare exception, however, was the late 1995 IPO of Pixar, in which 6.9 million shares were sold at $22 per share, raising a total of around $150 million. The Pixar offering was a great success because the company not only introduced new computer-generated technology in the making of Toy Story (released the week of the IPO), but also was backed by a multifilm major studio distribution agreement with Disney and led by a team of management and creative executives with impressive and well-established credentials.8

然而,一个罕见的例外是1995年底皮克斯的首次公开募股,其中以每股22美元的价格出售了690万股股票,总共筹集了约1.5亿美元。皮克斯的发行取得了巨大的成功,因为公司不仅在《玩具总动员》(Toy Story)的制作中引入了新的计算机生成技术(在IPO的那一周发布),而且还得到了与迪士尼签订的多部电影主要制片厂发行协议的支持,并由一个拥有令人印象深刻和良好声誉的管理和创意高管团队领导。8

Combination Deals 组合交易

Common stock is often sold in combination with other securities to appeal to a broader base of investors or to fit the financing requirements of the issuing company more closely. This is illustrated by the Telepictures equity offering of the early 1980s. At that time, Telepictures was primarily a syndicator of television series and feature films and a packager and marketer of made-for-television movies and news.

普通股通常与其他证券一起出售,以吸引更广泛的投资者,或更紧密地满足发行公司的融资要求。1980年代初Telepictures的股票发行就说明了这一点。当时,Telepictures主要是电视连续剧和故事片的辛迪加,以及为电视制作的电影和新闻的包装商和营销商。

As of its initial 1980 offering by a small New York firm, Telepictures had distribution rights to over 30 feature films and to about 200 hours of television programming in Latin America. The underwriting was in the form of 7,000 units, each composed of 350,000 common shares, warrants to purchase 350,000 common shares, and $7 million in 20-year 13% convertible subordinated debentures. In total, Telepictures raised $6.4 million in equity capital.

1980年,一家纽约的小公司首次发行,Telepictures拥有30多部故事片和大约200小时的拉丁美洲电视节目的发行权。承销形式为7,000个单位,每个单位由350,000股普通股,购买350,000股普通股的认股权证和700万美元的20年期13%可转换次级债券组成。Telepictures总共筹集了640万美元的股权资本。

Another illustration of a combination offering was that of De Laurentiis Entertainment Group Inc., which in 1986 separately but simultaneously sold 1.85 million shares of common stock and $65 million in 12.5% senior subordinated 15-year notes through a large New York underwriting firm. In this instance, the well-known producer Dino De Laurentiis contributed his previously acquired rights in the 245-title Embassy Films library and in an operational film studio in North Carolina to provide an asset base for the new public entity. Among several major films in the library were The Graduate, Carnal Knowledge, and Romeo and Juliet.

另一个组合发行的例子是德劳伦蒂斯娱乐集团公司,1986年,它通过一家大型纽约承销公司分别但同时出售了185万股普通股和6500万美元的12.5%的15年期优先次级债券。在这种情况下,著名制片人迪诺·德·劳伦蒂斯贡献了他以前在245个标题的大使馆电影图书馆和北卡罗来纳州的一个运营电影制片厂获得的权利,为新的公共实体提供资产基础。图书馆里的几部主要电影包括《毕业生》、《肉欲》和《罗密欧与朱丽叶》。

The underlying concept for this company, as well as for many other similar issues brought public at around the same time, was that presales of rights to pay cable, home video, and foreign theatrical distributors could be used to cover, or perhaps more than cover, direct production expenses on low-budget pictures. The subsequent difficulties experienced by this company and several others applying the same strategy, however, proved that the concept most often works better in theory than in practice. The reason is that companies in the production start-up phase of development normally encounter severe cash flow pressures unless they are fortunate enough to have a big box-office hit early on.9

这家公司的基本概念,以及大约在同一时间公开的许多其他类似问题,是付费有线电视,家庭视频和外国戏剧发行商的预售权可以用来支付,或者可能超过支付,低成本电影的直接制作费用。然而,这家公司和其他几家采用同样战略的公司随后遇到的困难证明,这一概念在理论上往往比在实践中更有效。原因是,处于开发制作启动阶段的公司通常会遇到严重的现金流压力,除非他们足够幸运,能够在早期获得巨大的票房收入。9

Limited Partnerships and Tax Shelters

有限合伙企业和避税天堂

Limited partnerships have in the past generally provided the opportunity to invest in movies, but with the government sharing some of the risk. In fact, before extensive tax-law adjustments in 1976, movie investments were among the most interesting tax-shelter vehicles ever devised. Prior to that revision, limited partners holding limited recourse or nonrecourse loans (i.e., in the event of default, the lender could not seize all of the borrower’s assets, thus making these loans without personal liability exposure) could write down losses against income several times the original amount invested; they could experience the fun and ego gratification of sponsoring movies and receive a tax benefit to boot.

过去,有限合伙制通常提供了投资电影的机会,但政府分担了部分风险。事实上,在1976年税法大规模调整之前,电影投资是有史以来最有趣的避税工具之一。在修订之前,持有有限追索权或无追索权贷款的有限合伙人(即,一旦发生违约,贷款人不能没收借款人的全部资产,从而使这些贷款(没有个人责任风险)可以将损失减记为原始投资额的几倍;他们可以体验赞助电影的乐趣和自我满足,并获得税收优惠靴子。

Such agreements were in the form of either purchases or service partnerships. In a purchase, the investor would buy the picture (usually at an inflated price) with, say, a $1 down payment and promise to pay another $3 with a nonrecourse loan secured by anticipated receipts from the movie. Although the risk was only $1, there was a $4 base to depreciate and on which to charge investment tax credits.

这种协议的形式是购买或服务伙伴关系。在购买中,投资者会以1美元的首付购买这部电影(通常是以虚高的价格),并承诺再支付3美元,并以电影的预期收入作为无追索权贷款的担保。虽然风险只有1美元,但有4美元的折旧基数,并在此基础上收取投资税收抵免。

In the service arrangement, an investor would become a partner in owning the physical production entity rather than the movie itself. Using a promissory note, deductions in the year of expenditure would again be a multiple of the actual amount invested – an attractive situation to individuals in federal tax brackets over 50%.

在服务安排中,投资者将成为拥有实体制作实体而不是电影本身的合作伙伴。使用期票,支出当年的扣除额将再次是实际投资额的倍数--这对联邦税级超过50%的个人来说是一个有吸引力的情况。

Tax-code changes applicable between 1976 and 1986 permitted only the amount at risk to be written off against income by film “owners” (within a strict definition). The code also specified that investment tax credits (equivalent to 6.67% of the total investment in the negative if more than 80% of the picture had been produced in the United States) were to be accrued from the date of initial release.10 Revised tax treatment also required investments to be capitalized – a stipulation that disallowed the service-partnership form.

1976年至1986年期间适用的税法变化只允许电影“所有者”(在严格定义内)从收入中注销风险金额。该守则还规定,投资税收抵免(如果超过80%的图片是在美国制作的,则相当于负面投资总额的6.67%)将从首次发布之日起累计。10.修订后的税务处理办法还要求将投资资本化-这一规定不允许服务伙伴关系形式。

Beginning with the Tax Reform Act of 1986, however, the investment tax credit that many entertainment companies had found so beneficial (it had helped them to conserve cash) was repealed. And significantly, so-called passive losses from tax shelters could no longer be used to offset income from wages, salaries, interest, and dividends. Such passive losses became deductible only against other passive-activity income. Since 1986, accordingly, notably fewer and differently structured movie partnerships have been offered to the public. Most of the more recent ones have appeared outside the United States.11

然而,从1986年的《税收改革法案》开始,许多娱乐公司认为非常有益的投资税收抵免(它帮助他们节省现金)被废除了。值得注意的是,所谓的避税被动损失不能再用来抵消工资、薪金、利息和股息收入。这种被动损失只能从其他被动活动收入中扣除。因此,自1986年以来,向公众提供的电影合作伙伴关系明显减少,而且结构不同。最近的大多数都出现在美国境外。11

More prototypical of the partnership structures of the 1980s, though, was the first (1983) offering of Silver Screen Partners. Strictly speaking, it was not a tax-sheltered deal. Here, Home Box Office (HBO, the Time Inc. wholesale distributor of pay-cable programs) guaranteed – no matter what the degree of box-office success, if any – return of full production costs on each of at least ten films included in the financing package.

然而,20世纪80年代合伙人结构的更典型的例子是第一次(1983年)提供银合伙人。严格地说,这不是一个避税交易。在这里,家庭票房(HBO,时代公司。收费有线电视节目的批发分销商)保证-无论票房成功的程度如何,如果有的话-至少10部电影中的每一部的全部制作成本都包括在融资方案中。

However, because only 50% of a film’s budget was due on completion, with five years to meet the remaining obligations, HBO in effect received a sizable interest-free loan, while benefiting from a steady flow of fresh product.12 For its 50% investment, HBO also retained exclusive pay television and television syndication rights and 25% of network TV sales. This meant that partners were largely relying on strong theatrical results, which, if they occurred, would entitle them to “performance bonuses.”13 Subsequent Silver Screen offerings with substantially the same structure, but of larger size (up to $400 million), were also used to finance Disney’s films (see Table 4.1).14

然而,由于一部电影只有50%的预算是在完成时到期的,还有五年的时间来偿还剩余的债务,HBO实际上得到了一笔相当大的无息贷款,同时受益于稳定的新产品流。12对于其50%的投资,HBO还保留了独家付费电视和电视辛迪加的权利以及25%的网络电视销售。这意味着,合伙人在很大程度上依赖于强劲的戏剧效果,如果出现这种情况,他们将有权获得“业绩奖金”。[13]随后发行的银电影也被用于资助迪士尼的电影,其结构基本相同,但规模更大(高达4亿美元)(见表4.1)。14

Table 4.1. Movie partnership financing: A selected sample, 1981–1987

表4.1. 电影合伙融资:1981-1987年选定样本

| Partnership 伙伴关系 | Total amount sought ($ millions) 要求赔偿总额(百万美元) | Minimum investment ($ thousands) 最低投资额(千美元) | Management fee as % of funds raised 管理费占所筹资金的百分比 | Limited partners’ share of profits 有限合伙人的利润份额 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Delphi III (January 1984) 德尔菲三世(1984年1月) | 60 | 5 | 1.16% for 1985–1989 then 0.67% for 1990–1994 1985-1989年1.16%,1990-1994年0.67% | 99% to limited partners, 1% to general partners entitled to 20% of all further cash distribution 99%分配给有限合伙人,1%分配给普通合伙人,有权获得所有进一步现金分配的20% |

| SLM Entertainment Ltd (October 1981) 1981年10月,SLM Entertainment Ltd | 40 | 10 | 2.5% of capitalization in 1982, 3% in 1983–1987, and 1% in 1988–1994 1982年资本化的2.5%,1983-1987年3%,1988-1994年1% | 99% until 100% returned, then 80% until 200% returned, and 70% afterward 99%直到100%返回,然后80%直到200%返回,然后70% |

| Silver Screen Partners (April 1983) 银伙伴(1983年4月) | 75 | 15 | 4% of budgeted film cost + 10% per year to the extent payment is deferred 预算电影成本的4%+每年10%,如果延期付款 | 99% until limited partners have received 100% plus 10% per annum on adjusted capital contribution, then 85% 99%,直到有限合伙人收到100%加上每年10%的调整后出资,然后是85% |

| Silver Screen Partners III (October 1986) 银幕拍档III(1986年10月) | 200 | 5 | 4% of budgeted film cost + 10% per year on overhead paid to partnership 预算电影成本的4%+每年支付给合作伙伴的间接费用的10% | 99% to investors until they have received an amount equal to their modified capital contribution plus 8% priority return 99%给投资者,直到他们收到相当于他们修改后的资本贡献加上8%优先回报的金额。 |

资料来源:伙伴关系招股说明书材料。

Such partnership units, though, are not the only types available. Quasi-public offerings that fall under the Securities and Exchange Commission’s Regulation D, for example, may still be used by independent filmmakers in structuring so-called Regulation D financing for small corporations or limited partnerships. Regulation D offerings allow up to 35 private investors to buy units in a corporation or a partnership without registration under the Securities Act of 1933.15

不过,这类伙伴关系单位并不是唯一可用的类型。例如,属于美国证券交易委员会D法规的准公开发行仍可能被独立电影制片人用于为小公司或有限合伙企业构建所谓的D法规融资。D法规允许最多35名私人投资者购买公司或合伙企业的单位,而无需根据1933年证券法进行注册。15

Limited-partnership financing appeals to studios because the attracted incremental capital permits greater diversification of film-production portfolios: Cash resources are enhanced, and there are then more films with which to feed ever-hungry distribution pipelines.16 Also, even though a feature might not, as determined by the partnership structure, provide any return to investors owning an equity percentage of the film, it may yet contribute to coverage of studio fixed costs (overhead) via earn-out of distribution fees that are taken as a percentage of the film’s rental revenues.17

有限合伙制融资对电影公司很有吸引力,因为所吸引的增量资本允许电影制作组合更加多样化:现金资源得到加强,然后有更多的电影可以满足日益饥渴的发行渠道。[16]此外,即使一部电影根据合伙人结构的决定,可能不会给拥有电影股权的投资者带来任何回报,但它仍然可以通过从电影租赁收入的一定百分比中获得的发行费来弥补制片厂的固定成本(管理费用)。17

From the standpoint of the individual investor, most movie partnerships cannot be expected to provide especially high returns on invested capital. Few of them have historically returned better than 10% to 15% annually. But such partnerships occasionally generate significant profits and they have provided small investors with opportunities to participate in major studio-packaged financings of pictures such as Annie, Poltergeist, Rocky III, Flashdance, and Who Framed Roger Rabbit. More often than not, however, when the pictures in such packages succeed at the box office, most investors would probably find that they could have done at least as well by investing directly in the common stock of the production and/or distribution companies (if for no other reason than considerations of liquidity) than in the related partnerships.

从个人投资者的角度来看,不能指望大多数电影合作伙伴能够提供特别高的投资资本回报。历史上,很少有公司的年回报率超过10%至15%。但这种合作偶尔会产生可观的利润,它们为小投资者提供了参与大型电影制片厂包装融资的机会,如《安妮》、《恶作剧鬼》、《洛基三世》、《闪电舞》和《谁陷害了兔子罗杰》。然而,通常情况下,当这种包装中的电影在票房上取得成功时,大多数投资者可能会发现,他们直接投资于制作和/或发行公司的普通股(如果没有其他原因,只是考虑到流动性)至少可以比相关的合伙企业做得更好。

Bank Loans 银行贷款

Established studios will normally be able to raise capital for general corporate purposes through debt or equity financing, or through commercial bank loans. In these situations, there is a considerable amount of flexibility as to the terms and types of financing that may be structured; a wide variety of corporate assets may be used as collateral.

已成立的电影公司通常能够通过债务或股权融资或通过商业银行贷款为一般企业目的筹集资金。在这些情况下,在可安排的融资的条件和类型方面有相当大的灵活性;各种各样的公司资产可用作抵押品。

For example, studios have recently been more willing to consider loan securitization structures similar to those used to create intermediate-term securities backed by packages of assets such as car and home equity loans. In the movie industry, investors contribute relatively small amounts of equity capital to form specially created “paper companies,” and banks then arrange for loans and for the sale of commercial paper and medium-term notes to fund production costs – with the contributed equity and the projected value of the films to be produced over a three-year period serving as collateral. In this way, production costs are kept off studio balance sheets, earnings can be smoothed, borrowing costs may be reduced, and some of the risks can be shifted to equity investors even though ownership rights eventually revert back to the studio.18

例如,电影公司最近更愿意考虑贷款证券化结构,类似于那些用于创建由汽车和房屋净值贷款等一揽子资产支持的中期证券的结构。在电影业,投资者投入相对较少的股本,成立专门的“票据公司”,然后银行安排贷款和销售商业票据和中期票据,为制作成本提供资金--投入的股本和三年内制作的电影的预计价值作为抵押。通过这种方式,制作成本不会出现在制片厂的资产负债表上,收益可以平滑,借贷成本可以降低,即使所有权最终会回到制片厂,一些风险也可以转移到股权投资者身上。18

Production loans to an independent producer, however, are quite another story. An independent producer may have little or no collateral backing except for presale contracts and other rights agreements relating directly to the production that is to be financed. As a practical matter, then, the bank, which views a film as a bundle of potentially valuable rights, must actually look to the creditworthiness of the various licensees for repayment not only of the loan itself but also of the interest on the loan. This accordingly makes a production loan more akin to accounts receivable financing than to a standard-term loan on the corporate assets of an ongoing business.19

然而,向独立生产商提供生产贷款则完全是另一回事。除了预售合同和其他直接与要融资的生产有关的权利协议外,独立生产者可能只有很少或没有抵押支持。因此,实际上,银行将电影视为具有潜在价值的权利的集合,因此,它不仅要偿还贷款本身,而且要偿还贷款利息,实际上必须考虑各个特许经营者的信誉。因此,这使得生产贷款更类似于应收账款融资,而不是对正在进行的企业的公司资产的标准期限贷款。19

From the producer’s standpoint, such bank loan financing may be attractive because it can provide a means of circumventing the high costs and the rigidities, both financial and artistic, that come with a studio’s distribution and financing deal. However, the fractionalization of distribution rights across many borders and across many different media absorbs time and effort that the producer might better apply to a project’s creative aspects.

从制片人的角度来看,这种银行贷款融资可能是有吸引力的,因为它可以提供一种手段,规避电影公司发行和融资交易所带来的高成本和财政和艺术上的僵化。然而,跨越许多边界和许多不同媒体的分销权的细分占用了制作人可能更好地应用于项目创意方面的时间和精力。

Private Equity and Hedge Funds

私人股本和对冲基金

Hollywood has always been dependent on large-scale financing and has often benefited from funding fervor that has materialized in unexpected places. In the 1980s, public equity was popular as a way to finance independent new studios such as Carolco. The end of the 1980s then brought direct investment from Japan into Columbia Pictures (Sony) and MCA (Matsushita). This was followed by a phase involving foreign banks (e.g., Credit Lyonnais and MGM) and insurance-backed investors. And later, German public equity and Middle Eastern sovereign wealth sources provided financial support.

好莱坞一直依赖于大规模融资,并经常受益于在意想不到的地方实现的融资热情。在20世纪80年代,公共股本作为一种为独立的新工作室(如Punchco)提供资金的方式很受欢迎。20世纪80年代末,日本对哥伦比亚电影公司(索尼)和MCA(松下)进行了直接投资。随后是一个涉及外国银行的阶段(例如,里昂信贷和米高梅)和保险支持的投资者。后来,德国公共股本和中东主权财富来源提供了财政支持。

This was followed (around 2004) by private equity and hedge funds, which had by then become much more active in funneling large pools of production capital into portfolios of films through special arrangements with both major studios and established independents.20 Such pools are collectively funded by pension plans and wealthy individuals and often seek to diversify into areas that are alternatives to stocks, bonds, and real estate. As such, these pools contributed some of the financing that had previously been done through tax shelters and partnerships. Along the same lines, a concept of a futures (i.e., derivatives) market was also developed.21

紧随其后(2004年左右)的是私募股权和对冲基金,它们通过与主要制片厂和老牌独立制片商的特殊安排,在电影投资组合中投入了大量的制作资本。[20]这些资金池由养老金计划和富有的个人共同出资,往往寻求多样化,进入股票、债券和真实的房地产以外的领域。因此,这些资金池提供了以前通过避税和伙伴关系提供的部分资金。沿着同样的思路,期货的概念(即,衍生品市场也得到了发展。21

With their ability to commit several hundred million dollars to a slate of perhaps 10 or 20 pictures at a time, these funds provided a welcome source of capital that allowed studios to retain territorial rights as well as a large amount of control over creative issues. Studios, in effect, were able to transfer some of the risks – including those relating to financing, completion, and marketplace performance – to the funds. And the funds, for their part, expected to receive above-average returns while at the same time lowering their overall risk through diversification into (what are presumed to be relatively low-covariance) film asset investments.

这些基金能够一次性为10部或20部电影投入数亿美元,为电影公司提供了一个受欢迎的资金来源,使电影公司能够保留领土权利以及对创意问题的大量控制权。实际上,工作室能够将一些风险--包括与融资、完成和市场表现有关的风险--转移到基金上。而这些基金则期望获得高于平均水平的回报,同时通过分散投资(被认为是相对低协方差的)电影资产投资来降低整体风险。

The typical deal is for an even split of carefully defined profits after a studio deducts a 12% to 15% distribution fee. The studio often also puts up money for prints and advertising (p&a), which is recouped before profits are split. In structuring a deal, large investment banks will normally provide senior debt instruments that are paid back first and that will be priced to reflect this relatively low-risk position. Private equity or hedge funds then take on the progressively riskier positions. For “mezzanine” investors, the expected return is at least 15% (annually), whereas equity players will expect the return to be at least 20%. The guiding principle is that diversification over a large portfolio of film projects will considerably reduce risk exposure for all participants.

典型的交易是在电影公司扣除12%到15%的发行费后,平均分配精心定义的利润。工作室还经常为印刷品和广告(p&a)投入资金,这些资金在利润分配之前得到收回。在安排交易时,大型投资银行通常会提供优先债务工具,这些工具首先得到偿还,定价将反映这种相对低风险的头寸。然后,私人股本或对冲基金承担风险越来越高的头寸。对于“夹层”投资者,预期回报率至少为15%(每年),而股票投资者预期回报率至少为20%。指导原则是,分散投资于一个庞大的电影项目组合将大大减少所有参与者的风险。

Nevertheless, unlike what happens in other industries, such structural arrangements for funding are in fact a form of venture capital investment in which the high-risk fund money is invested early and up front, but with returns seen only later, after the studio has first recovered various expenses – p&a and distribution fees.22 Because of such deductions, the studios will always retain a senior and less risky position as compared with the outside investors.

然而,与其他行业不同的是,这种结构性的资金安排实际上是一种风险投资,高风险的基金资金在早期和早期投入,但回报要在工作室首先收回各种费用后才能看到-- P&A和发行费。[22]由于这种扣减,制片厂与外部投资者相比,将始终保持一种高级和风险较小的地位。

Independent filmmakers who are not in some way tied to the studio system have also developed innovative financing alternatives that are potentially less risky than direct equity investments. Borrowing against tax credits that are offered in several states can often be advantageously used. For example, an $8.5 million advance contingent on a state granting producer incentives worth $10 million (upon which the investor retains the difference) might be arranged. Another alternative might be “finishing funds” in which a film needs additional capital for completion and the investor is the first to be repaid. There are also p&a funds designed to raise capital for marketing and advertising of a completed film and on which perhaps up to a 15% return might be earned. Funds can also be lent against presold domestic and foreign distribution rights.23

与制片厂系统没有某种联系的独立电影制片人也开发了创新的融资方式,这些方式的风险可能低于直接股权投资。在几个州提供的税收抵免贷款往往可以有利地使用。例如,可以安排一笔850万美元的预付款,条件是国家给予生产者价值1000万美元的奖励(投资者保留差额)。另一种选择可能是“完成基金”,即一部电影需要额外的资金才能完成,投资者是第一个得到偿还的人。也有为一部已完成的电影的市场营销和广告筹集资金的p&a基金,其回报率可能高达15%。也可以根据预售的国内和国外分销权发放贷款。23

4.3 Production Preliminaries

The Big Picture 大局

Costs in this industry always tend to rise faster than in many other sectors of the economy because moviemaking procedures, although largely standardized, must be uniquely applied to each project and because efficiencies of scale are not easily attained. But other factors also pertain.

电影业的成本总是比其他许多经济部门上升得快,因为电影制作程序虽然基本上是标准化的,但必须独特地适用于每个项目,而且规模效益不容易实现。但其他因素也与此相关。

For example, during the 1970s, fiscal sloppiness pervaded the industry as soon as it became relatively easy to finance productions using other people’s tax-sheltered money. Indulgence of “auteurs,” who demanded unrestricted funding in the name of creative genius, further contributed to budget bloating. And “bankable” actors and directors (popular personalities expected to draw an audience by virtue of their mere presence) came to command millions of dollars for relatively little expenditure of time and effort. It was only a short while before everyone else involved in a production also demanded more.24

例如,在20世纪70年代,当用别人的避税资金为生产提供资金变得相对容易时,财政上的草率就弥漫了整个行业。放纵“august”,以创造性天才的名义要求无限制的资金,进一步助长了预算膨胀。而“票房收入高”的演员和导演(受欢迎的人物,预计将吸引观众凭借他们的存在)来指挥数百万美元的相对较少的时间和精力的支出。只是一会儿,其他参与制作的人也要求更多。24

By the early 1980s, the burgeoning of new-media revenue sources, primarily in cable and home video, also naturally attracted (until the 1986 tax-code changes) relatively large and eager capital funding commitments for investments in movie and television ventures. But none of this could have gone quite so far without the ready availability of funds from so-called junk-bond financing, an upward-trending domestic stock market, and the spillover of wealth and easy credit from Japan’s “bubble” economy.25 In fact, it was not until the early 1990s, when more stringent limitations on access to bank financing were imposed, and when movie stock takeover speculation was cooled by the onset of an economic recession, that cost pressures somewhat abated.

到20世纪80年代初,新媒体收入来源(主要是有线电视和家庭视频)的迅速发展也自然吸引了(直到1986年税法改变)相对较大且渴望的资本投资承诺,用于投资电影和电视企业。但如果没有所谓的垃圾债券融资、国内股市的上涨趋势以及日本“泡沫”经济带来的财富和宽松信贷的溢出效应,这一切都不可能走得这么远。[25]事实上,直到1990年代初,对获得银行融资施加了更严格的限制,电影股票收购投机因经济衰退的开始而降温,成本压力才有所减轻。

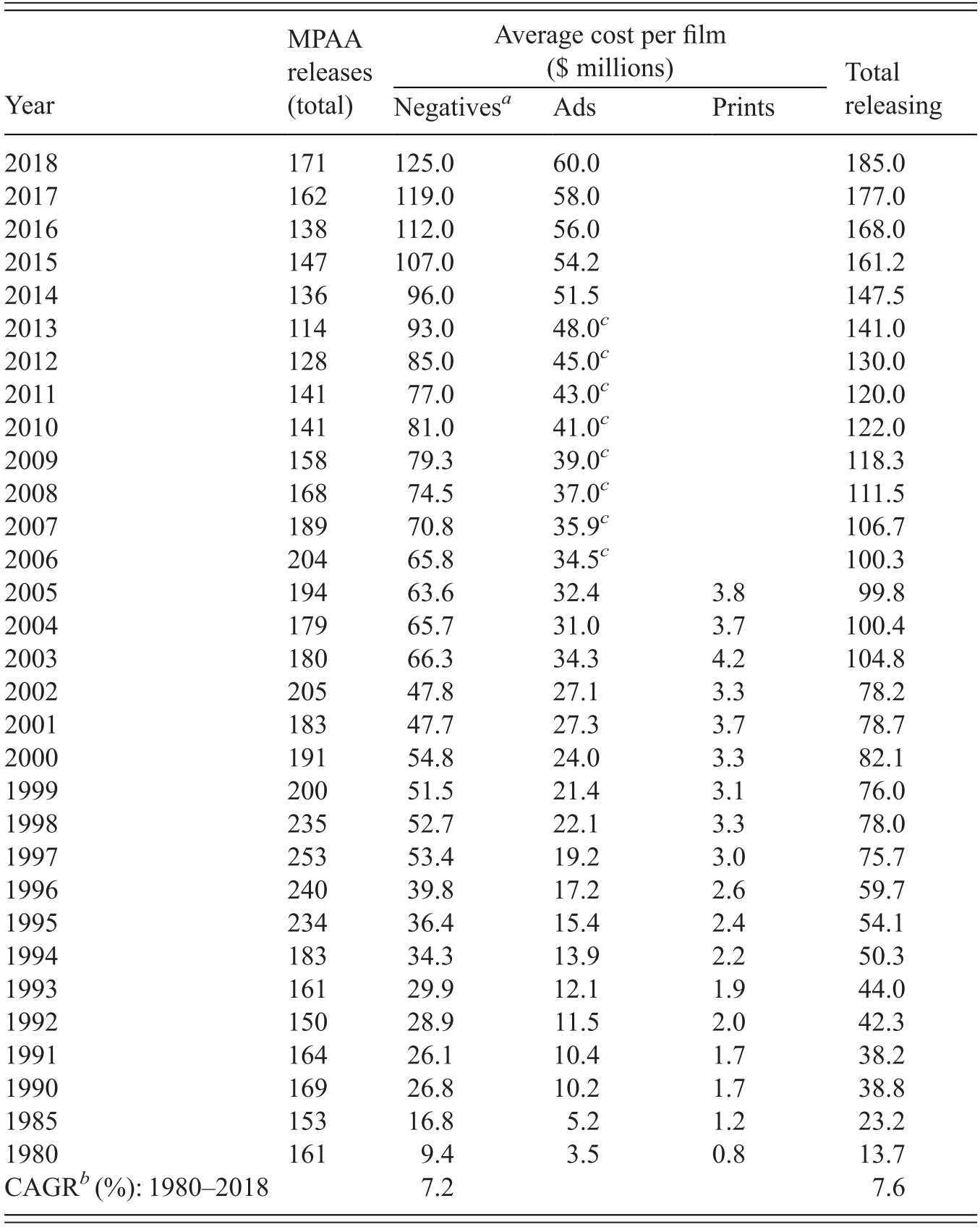

Data from the Motion Picture Association of America (Table 4.2) indicate that between 1980 and 2007, the negative cost, which is the average cost of production (including studio overhead and capitalized interest) for features produced by the majors, rose at a compound annual rate of more than 7.0%, far above the overall inflation rate for this period. By 2007, the last year of officially available data – ostensibly because of the increasing difficulty of arriving at representative calculations – the average cost of producing an MPAA-member film had risen to approximately $70 million.26 And as of 2019, a reasonable extrapolation of the prior trend would suggest that such costs have risen to around $125 million given that studios have largely decided to release fewer films and concentrate instead on development of relatively expensive (>$130 million) tentpole projects.

美国电影协会的数据(表4.2)表明,1980年至2007年间,负成本,即各大电影公司制作的影片的平均制作成本(包括制片厂管理费用和资本化利息),以超过7.0%的复合年增长率上升,远高于同期的总体通货膨胀率。到了2007年,也就是官方数据的最后一年--表面上是因为越来越难以得出有代表性的计算结果--制作一部MPAA成员电影的平均成本已经上升到大约7000万美元。[26]截至2019年,对先前趋势的合理推断表明,鉴于电影公司在很大程度上决定减少电影发行量,转而专注于开发相对昂贵(> 1.3亿美元)的帐篷项目,此类成本已上升至约1.25亿美元。

Table 4.2. Marketing and negative cost expenditures for major film releases, 1980–2018

表4.2. 1980-2018年主要电影发行的营销和负成本支出

| Year 年 | MPAA releases (total) MPAA发布(总数) | Average cost per film ($ millions) 每部影片的平均成本(百万美元) | Total releasing 总释放量 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Negativesa 阴性a | Ads 广告 | Prints 指纹 | |||

| 2018 | 171 | 125.0 | 60.0 | 185.0 | |

| 2017 | 162 | 119.0 | 58.0 | 177.0 | |

| 2016 | 138 | 112.0 | 56.0 | 168.0 | |

| 2015 | 147 | 107.0 | 54.2 | 161.2 | |

| 2014 | 136 | 96.0 | 51.5 | 147.5 | |

| 2013 | 114 | 93.0 | 48.0c | 141.0 | |

| 2012 | 128 | 85.0 | 45.0c | 130.0 | |

| 2011 | 141 | 77.0 | 43.0c | 120.0 | |

| 2010 | 141 | 81.0 | 41.0c | 122.0 | |

| 2009 | 158 | 79.3 | 39.0c | 118.3 | |

| 2008 | 168 | 74.5 | 37.0c | 111.5 | |

| 2007 | 189 | 70.8 | 35.9c | 106.7 | |

| 2006 | 204 | 65.8 | 34.5c | 100.3 | |

| 2005 | 194 | 63.6 | 32.4 | 3.8 | 99.8 |

| 2004 | 179 | 65.7 | 31.0 | 3.7 | 100.4 |

| 2003 | 180 | 66.3 | 34.3 | 4.2 | 104.8 |

| 2002 | 205 | 47.8 | 27.1 | 3.3 | 78.2 |

| 2001 | 183 | 47.7 | 27.3 | 3.7 | 78.7 |

| 2000 | 191 | 54.8 | 24.0 | 3.3 | 82.1 |

| 1999 | 200 | 51.5 | 21.4 | 3.1 | 76.0 |

| 1998 | 235 | 52.7 | 22.1 | 3.3 | 78.0 |

| 1997 | 253 | 53.4 | 19.2 | 3.0 | 75.7 |

| 1996 | 240 | 39.8 | 17.2 | 2.6 | 59.7 |

| 1995 | 234 | 36.4 | 15.4 | 2.4 | 54.1 |

| 1994 | 183 | 34.3 | 13.9 | 2.2 | 50.3 |

| 1993 | 161 | 29.9 | 12.1 | 1.9 | 44.0 |

| 1992 | 150 | 28.9 | 11.5 | 2.0 | 42.3 |

| 1991 | 164 | 26.1 | 10.4 | 1.7 | 38.2 |

| 1990 | 169 | 26.8 | 10.2 | 1.7 | 38.8 |

| 1985 | 153 | 16.8 | 5.2 | 1.2 | 23.2 |

| 1980 | 161 | 9.4 | 3.5 | 0.8 | 13.7 |

| CAGRb (%): 1980–2018 CAGRB(%):1980-2018 | 7.2 | 7.6 | |||

a Negative costs ($ millions) for the years 1975 to 1979 were $3.1, $4.2, $5.6, $5.7, and $8.9, respectively. Costs include studio overhead and capitalized interest. Cost estimates for after 2008 are by author. Data frequently revised.

a1975年至1979年的负成本(百万美元)分别为3.1美元、4.2美元、5.6美元、5.7美元和8.9美元。成本包括制片厂管理费和资本化利息。2008年后的成本估计是由作者。数据经常被修改。

b Compound annual growth rate.

B复合年增长率。

c Prints and ads combined in releasing cost estimates after 2005.

c2005年后公布的费用估计数中印刷品和广告合并计算。

资料来源:美国电影协会和作者估计。

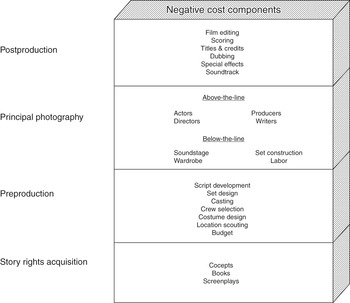

Even under the best of circumstances, though, production budgets are not easy to control as there are thousands of expense items to be tracked.27 The basic cost components that go into the making of a film negative, for example, are illustrated in Figure 4.1.

然而,即使在最好的情况下,生产预算也不容易控制,因为有成千上万的费用项目需要跟踪。[27]例如,图4.1说明了制作一张底片的基本成本构成。

Figure 4.1. Negative cost components.

图4.1. 负成本部分。

In the category of above-the-line costs – that is, the costs of a film’s creative elements, including cast and literary property acquisition (but not deferments) – contracts are signed and benefits and payments administered for sometimes hundreds of people.

在线上成本的类别中-即电影的创意元素的成本,包括演员和文学财产的获取(但不包括延期)-签署合同,有时为数百人管理福利和付款。

Good coordination is also required in budgeting below-the-line costs – the costs of crews and vehicles, transportation, shelter, and props.28 These are further arranged into production, post-production, and total other categories which include insurance and general expenses. For each film wardrobes and props must be made or otherwise acquired, locations must be scouted and leases arranged, and scene production and travel schedules must be meticulously planned. Should any one of those elements fall significantly out of step (as happens when the weather on location is unexpectedly bad, or when a major actor takes ill or is injured), expenses skyrocket. At such points of distress, a film’s completion bond insurance arrangements become significant because completion guarantors have the option to lend money to the producer to finish the film, to take full control of the film and finish it, or to abandon the film altogether and repay the financiers.29 Additional below-the-line costs also would be incurred in postproduction activities.30

在预算线下成本时也需要良好的协调--人员和车辆、运输、住所和道具的成本。28这些费用进一步分为制作、后期制作和包括保险和一般费用在内的其他类别。对于每一部电影来说,服装和道具必须制作或以其他方式获得,地点必须侦察和租赁安排,场景制作和旅行时间表必须精心计划。如果其中任何一个因素严重失调(例如当拍摄地点的天气意外恶劣,或者主要演员生病或受伤时),费用就会飙升。在这种困境中,电影的完成保证金保险安排变得重要,因为完成担保人可以选择借钱给制片人完成电影,完全控制电影并完成它,或者完全放弃电影并偿还金融家。29.后期制作活动也将产生额外的线下费用。30

In general, the smaller the budget, the higher will be the percentage of the budget spent on below-the-line costs and vice versa. But, interestingly, the larger the budget, the more a distributor would likely be willing to pay for rights because – regardless of cast, script, or anything else – financing requirements are usually calculated as a percentage of the budget.

一般来说,预算越少,预算中用于线下费用的百分比就越高,反之亦然。但是,有趣的是,预算越大,发行商可能就越愿意为版权付费,因为--不管演员阵容、剧本或其他什么--融资要求通常都是按预算的百分比计算的。

Labor Unions and Guilds 工会和行业协会

Unions have an important influence on the economics of filmmaking, beginning with the first phase of production. Indeed, union guidelines for compensation at each defined level of trade skill allow preliminary below-the-line production cost estimates to be determined with a fair degree of accuracy. Major unions in Hollywood include

工会对电影制作的经济有着重要的影响,从制作的第一阶段开始。事实上,工会对每一个确定的行业技能水平的补偿指导方针允许以相当准确的程度确定初步的线下生产成本估计。好莱坞的主要工会包括

International Alliance of Theatrical and Stage Employees (IATSE)

国际戏剧和舞台工作者联盟(IATSE)SAG-AFTRA (Screen Actors Guild merged with American Federation of Television and Radio Artists)

SAG-AFTRA(演员工会与美国电视和广播艺术家联合会合并)

Individuals belonging to these unions will normally be employed in the production of all significant motion pictures. The unions, in turn, will negotiate for contract terms with the studios’ bargaining organization, the Alliance of Motion Picture and Television Producers (AMPTP). Generally, these organizations and their members receive so-called residual payments (evolved out of old practices in vaudeville and on Broadway), which, for theatrical films, are calculated on gross revenues obtained – whether or not the production is profitable – from video, television, and other nontheatrical sources.31 The Producers Guild of America, however, is not strictly a labor union, as it does not negotiate working conditions or set wages and its members do not receive residuals.

属于这些工会的个人通常会受雇于所有重要电影的制作。反过来,工会将与电影公司的谈判组织电影和电视制片人联盟(AMPTP)谈判合同条款。一般来说,这些组织及其成员会收到所谓的剩余报酬(从歌舞杂耍和百老汇的旧做法演变而来),对于戏剧电影来说,这是根据从视频、电视和其他非戏剧来源获得的总收入计算的--无论制作是否有利可图。[31]然而,严格来说,美国生产者协会并不是一个工会,因为它不谈判工作条件或设定工资,其成员也不领取剩余工资。

Still, it is possible to produce a film with no noticeable difference in quality for up to 40% less in nonunion or flexible-union territories outside of Hollywood and independent producers may sometimes attempt to reduce below-the-line costs by filming in such territories.32 Studios may sometimes also make use of an IATSE contract provision (Article 20) that allows the financing of low-budget nonunion movies and television shows if the studio claims to have no creative control.33

尽管如此,在好莱坞以外的非工会或灵活工会地区制作一部质量没有明显差异的电影是可能的,而且独立制片人有时可能会试图通过在这些地区拍摄来降低线下成本。[32]制片厂有时也可以利用IATSE合同条款(第20条),如果制片厂声称没有创作控制权,则允许为低预算的非工会电影和电视节目提供资金。33

4.4 Marketing Matters

4.4营销事项

Distributors and Exhibitors

经销商和参展商

Sequencing. 测序

After the principal production phase has been completed, thousands of details still remain to be monitored and administered. Scoring, editing, mixing sound and color, making prints at the film laboratory, and conversion to digital formats are but a few of the essential steps. Once the film is in the postproduction stages, however, perhaps the most critical preparations are those for distribution and marketing. It is somewhere within this last creative phase that the almost total power and control until then wielded by a project’s producer and director are passed to people in the distribution and marketing organization.

在主要生产阶段完成后,仍有数千个细节有待监测和管理。配乐、编辑、混音和调色、在电影实验室制作拷贝以及转换为数字格式只是其中的几个基本步骤。然而,一旦电影进入后期制作阶段,也许最关键的准备工作是发行和营销。正是在这最后一个创造性阶段的某个地方,一个项目的制片人和导演所拥有的几乎全部的权力和控制权被传递给了分销和营销组织的人员。

Sequential distribution patterns are determined by the principle of the second-best alternative – a corollary of the price-discriminating market-segmentation strategies discussed in Chapter 1. That is, films are normally first distributed to the market that generates the highest marginal revenue over the least amount of time. They then “cascade” in order of marginal-revenue contribution down to markets that return the lowest revenues per unit of time. This has historically meant theatrical release, followed by licensing to pay-cable program distributors, home video, television networks, and finally local television syndicators. Distribution “is all about maximizing discrete periods of exclusivity.”34

序列分布模式是由次优选择原则决定的--这是第一章讨论的价格歧视市场分割策略的一个推论。也就是说,电影通常首先发行到在最短时间内产生最高边际收入的市场。然后,他们按照边际收入贡献的顺序“级联”到单位时间内回报最低的市场。从历史上看,这意味着剧院发行,其次是向付费有线电视节目发行商、家庭视频、电视网络发放许可证,最后是地方电视辛迪加。“分销”就是最大限度地增加不连续的排他性。34

However, because the amounts of capital invested in features have become so large and the pressures for faster recoupment so great, there has been movement toward earlier opening of all windows (Figure 4.2) – including the worldwide initial theatrical. An estimated 95% of total box office receipts are now generated within the first month. Changes in historical window time sequencing have already occurred in DVDs and are also occurring for video-on-demand, Internet downloads, and mobile, small-screen viewing platforms.35

然而,由于投入到电影中的资本数额已经变得如此之大,而且要求更快收回成本的压力也如此之大,因此出现了提前开放所有窗口的趋势(图4.2)--包括世界范围内的第一家影院。据估计,95%的票房收入都是在第一个月内产生的。历史窗口时间顺序的变化已经发生在DVD中,也发生在视频点播、互联网下载和移动的小屏幕观看平台上。35

Figure 4.2. Typical market windows from release date, circa 2018.

图4.2. 从发布日期开始的典型市场窗口,大约2018年。

Sequencing is always a marketing decision that attempts to maximize income and it is often sensible for profit-maximizing distributors to price-discriminate in different markets or “windows” by selling the same product at different prices to different buyers.36 Control of windows creates scarcity, which is crafted through use of contractually specified terms and times of exploitation exclusivity that are achieved through the use of what are known as “holdbacks.” In so doing, recent films are, in effect, quarantined (by the major pay-cable networks) for periods lasting to as many as five to seven years, during which time the films are accordingly unavailable to online service distributors.37

排序总是一种试图使收入最大化的营销决策,对于利润最大化的分销商来说,通过以不同的价格向不同的买家出售相同的产品,在不同的市场或“窗口”进行价格歧视通常是明智的。36对窗口的控制造成稀缺性,而稀缺性是通过使用合同规定的条款和利用排他性的时间来制造的,这些条款和时间是通过使用所谓的“保留”来实现的。这样做,最新的电影实际上被隔离(由主要的付费有线电视网络)长达五到七年,在此期间,电影相应地无法向在线服务分销商提供。37

It should not be surprising to find, however, that, shifts in sequencing strategies occur as new distribution technologies emerge and as older ones fade in relative importance.38 For example, the Internet’s ability to make films instantly available anywhere now requires simultaneous worldwide day-and-date theatrical or DVD release for major projects. Such “windowing” is a way in which the public-good characteristics of movies used as television programs can be fully exploited.39

然而,随着新的分销技术的出现和旧技术的相对重要性逐渐减弱,测序策略的变化也就不足为奇了。38.例如,因特网使电影在任何地方都能立即播放的能力,现在需要在全世界同时为重大项目发行每日影院或DVD。这样的“开窗”是一种可以充分利用电影作为电视节目的公益特性的方式。39

As studios increasingly interact directly with their ultimate audiences through social media and cloud-based digital-locker services, the behavioral data that are thereby generated also enable marketing to become more efficient.40 Such behavioral data are already well established at digital distributors like Amazon, Netflix (subscription video-on-demand or SVOD), and iTunes.

随着电影公司越来越多地通过社交媒体和基于云的数字储物柜服务与最终观众直接互动,由此产生的行为数据也使营销变得更加有效。[40]这种行为数据已经在亚马逊、Netflix(订阅视频点播或SVOD)和iTunes等数字分销商那里得到了很好的建立。

Distributor–Exhibitor Contracts.

经销商-参展商合同。

Distributors normally design their marketing campaigns with certain target audiences in mind. And marketing considerations are prominent in a studio’s decision to make (i.e., green-light) or otherwise acquire a film for distribution: In the earliest stages, marketing departments will attempt to forecast the prospects for a film in terms of its potential appeal to different audience demographic segments, with male/female, young (under 25)/old (known as “four quadrant”), and sometimes also ethnic/cultural being the main categorizations.41

分销商通常在设计营销活动时会考虑到某些目标受众。营销方面的考虑在工作室的决策中很突出(即,在最初阶段,市场营销部门将试图根据电影对不同观众群体的潜在吸引力来预测电影的前景,其中男性/女性,年轻人(25岁以下)/老年人(称为“四象限”),有时也是种族/文化的主要分类。41

Distributors will then typically attempt to align their releases with the most demographically suitable theaters, subject to availability of screens and to previously established relationships with the exhibition chains. They accomplish this by analyzing how similar films have performed previously in each potential location and then by developing a release strategy that provides the best possible marketing mix, or platform, for the picture.42 Sometimes the plan may involve slow buildup through limited local or regional (platform) release; at other times, it may involve broad national release on literally thousands of screens simultaneously.

然后,分销商通常会尝试将其发行与人口统计学上最合适的剧院相结合,这取决于屏幕的可用性以及先前与展览链建立的关系。他们通过分析类似电影在每个潜在地点的表现,然后制定一个发行策略,为电影提供最佳的营销组合或平台,来实现这一目标。[42]有时,该计划可能涉及通过有限的本地或区域(平台)发布来缓慢积累;在其他时候,它可能涉及同时在数千个屏幕上进行广泛的全国发布。

Although no amount of marketing savvy can make a really bad picture play well, an intelligent strategy can almost certainly improve the box-office (and ultimately the video and cable) performance of a mediocre picture. It has accordingly now become characteristic of distributors to negotiate arrangements with exhibitors for specific theater sites and auditorium sizes.

尽管再多的营销技巧也不能让一部糟糕的电影发挥得很好,但一个聪明的策略几乎可以肯定地提高一部平庸电影的票房(最终是视频和有线电视)表现。因此,与参展商就具体的剧院场地和礼堂大小进行谈判安排已成为分销商的特点。

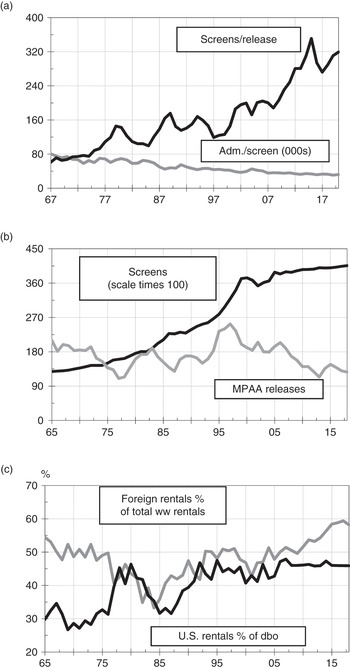

However, instead of negotiating, distributors may also sometimes elect, several months in advance of release, to send so-called bid letters to theaters located in regions in which they expect (because of demographic or income characteristics) to find audiences most responsive to a specific film’s theme and genre.43 This would normally be the preferred method of maximizing distributor revenues at times when the relative supply of pictures (to screens) is limited, as happened in the late 1970s (Figure 4.3a). Theaters that express interest in showing a picture then usually accept the terms (i.e., the implied cost of film rental and the playing times) suggested by the distributor’s regional branch exchange (sales office).

然而,发行商有时也会选择在上映前几个月向位于他们期望(由于人口统计或收入特征)发现观众对特定电影主题和类型最敏感的地区的影院发送所谓的投标函,而不是谈判。[43]在20世纪70年代后期(图4.3 a),当(对屏幕的)图片相对供应有限时,这通常是最大化发行商收入的首选方法。表示有兴趣放映电影的影院通常会接受这些条款(即,电影租赁的隐含成本和播放时间)。

Figure 4.3. Exhibition industry trends, 1965–2018. (a) Screens per release and admissions per screen, (b) Number of screens and number of MPAA-member releases, and (c) Rentals percentages: Foreign versus total, and as a percentage of U.S. box-office receipts.

图4.3. 展览业趋势,1965-2018。(a)每次上映的银幕数和每次上映的入场人数,(B)银幕数和MPAA会员上映的银幕数,以及(c)租金百分比:外国与总数,以及占美国票房收入的百分比。

Such contracts between distributors and exhibitors are usually of the boilerplate variety (fairly standard from picture to picture) and are arranged for large theater chains by experienced film bookers who bid for simultaneous runs in several theaters in a territory. Smaller chains or individual theaters might also use a professional agency for this purpose. The key phrases used in all contracts are screens, which refers to the number of auditoriums, and playdates (sometimes called engagements), which refers to the theater booked (even if the theater shows the film on several screens at the same location).

发行商和放映商之间的这种合同通常是样板文件(从一张图片到另一张图片都相当标准),由经验丰富的电影预订者为大型连锁影院安排,他们在一个地区的几家影院同时投标。较小的连锁影院或个体影院也可能为此目的使用专业机构。所有合同中使用的关键词是屏幕,指的是放映厅的数量,播放日期(有时称为约定),指的是预订的剧院(即使剧院在同一地点的几个屏幕上放映电影)。

The most common types of box office allocation contracts currently in use fall into two main categories:44

目前使用的最常见的票房分配合同类型分为两大类:

Straight aggregate percentages, in which a flat percentage of box office gross applied to all weeks of a film’s run are agreed to prior to the picture’s opening. Here exhibitors pay the same percentage for all weeks, which solves for them the problem that most of the gross is now concentrated in the first two weeks. Under older contracts, this would have cost exhibitors more.

直接累计百分比,即在电影上映前,电影上映的所有周的票房总收入的统一百分比。在这里,参展商为所有周支付相同的百分比,这为他们解决了大部分总收入集中在前两周的问题。根据旧的合同,这将使参展商付出更高的代价。Scalable aggregate percentages, in which for all play-weeks in the U.S. and Canada combined, a graduated ascending scale of the total is negotiated in advance of release, with film rental percentages for each picture determined by the gross thresholds the picture reaches. Here, there is no longer a need to estimate potential rentals percentages on a local theater circuit or regional basis as the benchmark is established nationally across-the-board. Scaling thus tends to reduce volatility of results for both exhibitors and distributors.

可缩放的总百分比,其中对于美国和加拿大的所有播放周,在发布之前协商了总额的渐进式递增比例,每部电影的电影租赁百分比由电影达到的总阈值确定。在这里,不再需要估计潜在的租金百分比在当地剧院电路或区域的基础上,因为基准是建立在全国全面。因此,规模化往往会减少参展商和分销商结果的波动性。

Still, there can be variations. Arrangements may entail specified runs limited to only two or four weeks. And in the early 1970s, the film Billy Jack received wide publicity for its distribution through “four-wall” contracts. Here, the distributor in effect rents the theater (four walls) for a fixed weekly fee, pays all operating expenses, and then mounts an advertising blitz on local television to attract the maximum audience in a minimal amount of time. Yet another simple occasional arrangement is flat rental, where the exhibitor (usually in a small, late-run situation) pays a fixed fee to the distributor for the right to show the film during a specified period.

不过,可能会有变化。这些安排可能需要规定仅限于两周或四周的特定运行。在20世纪70年代初,电影《比利杰克》因其通过“四面墙”合同的发行而受到广泛宣传。在这里,发行商实际上以固定的周租金租用剧院(四面墙),支付所有运营费用,然后在当地电视台上进行广告闪电战,以在最短的时间内吸引最多的观众。另一种简单的临时安排是公寓租金,放映商(通常是小规模的,后期放映的情况下)向发行商支付固定费用,以获得在特定时期内放映电影的权利。

There are also simple aggregate booking contracts in which all box-office revenue is split by a negotiated percentage formula that does not contain provision for the theater’s expenses – i.e., the house “nut”, which includes location rents and telephone, electricity, insurance, and mortgage payments and is largely a function of the quality of the theater location, number of screens, and number of seats. With such arrangements, box-office receipts of say, $10,000 might be split 55% for the distributors and 45% for the exhibitors, so that the theater would retain $4,500.

也有简单的合计预订合同,其中所有票房收入都按商定的百分比公式分割,该公式不包含剧院费用的规定-即,房子的“坚果”,包括位置租金和电话,电力,保险和抵押贷款付款,主要是剧院位置,屏幕数量和座位数量的质量的函数。在这样的安排下,比如说,10,000美元的票房收入可能会被分配给发行商55%,参展商45%,这样剧院将保留4500美元。

Although they are not used to anywhere near the same extent as previously – as in times prior to home video, Internet downloading and streaming, video-on-demand, and other viewing methods – old-style conventional contracts (i.e., what are known as standard agreements) between distributors and exhibitors had typically split box office revenues according to formulas that involved sliding scales, “nuts,” and “floors.”45

尽管它们的使用程度与以前不同--如在家庭视频、互联网下载和流媒体、视频点播和其他观看方法之前的时代--旧式的传统合同(即,发行商和放映商之间的所谓标准协议)通常根据涉及滑动比例,“螺母”和“地板”的公式来分配票房收入。45

Lease terms may include bid or negotiated clearances, which provide time and territorial (i.e., zoning) exclusivity for a theater as well as conditions relating to the size of the auditorium.46 No exhibitor would want to meet high terms for a film that would soon (or, even worse, simultaneously) be playing at a competitor’s theater down the block. In addition, such contracts usually include a holdover clause that requires theaters to extend exhibition of the film another week (and also perhaps revert to payment of a higher percentage) if the previous week’s revenue exceeds a predetermined amount. The distributor’s gross (otherwise known as rentals) is thus in effect received for a carefully defined conditional lease of a film over a specified period.

租赁条款可能包括投标或谈判许可,提供时间和领土(即,分区)剧院的排他性以及与观众席的大小有关的条件。46没有一个放映商愿意为一部很快(或者更糟糕的是,同时)在街区外的竞争对手的电影院上映的电影支付高额费用。此外,这类合同通常包括延期条款,要求影院在前一周的收入超过预定数额的情况下,将电影的放映时间延长一周(也可能恢复支付更高比例的费用)。因此,发行商的毛收入(也称为租金)实际上是在一段特定时期内对电影进行仔细界定的有条件租赁。

Should a picture not perform up to expectations, the distributor also usually has the right to a certain minimum or floor payment. These minimums are direct percentages (often more than half) of box-office receipts prior to subtraction of house expenses, but any previously advanced (or guaranteed) exhibitor monies can be used to cover floor payments owed. For many films (especially for those that flop), the distributor might also reduce (in a nonbid situation) the exhibitor’s burden through a quietly arranged settlement, which for multiplexes might sometimes include extending an underperforming picture’s run by moving it over to smaller auditoriums (having lower house nuts).47

如果一部电影没有达到预期,分销商通常也有权获得一定的最低或最低付款。这些最低限额是扣除票房费用之前票房收入的直接百分比(通常超过一半),但任何先前预付的(或保证的)参展商资金都可以用来支付所欠的最低付款。对于许多电影(特别是那些失败的电影),发行商也可能通过悄悄安排的解决方案来减轻(在非投标情况下)放映商的负担,对于多厅影院来说,这有时可能包括通过将表现不佳的电影转移到较小的放映厅(有较低的电影院)来延长放映时间。47

The upshot is that, on the average, exhibitors have typically retained almost 50% of box-office receipts in the United States (but closer to 70% in the United Kingdom and 75% in China). Yet given that many films nowadays experience rapid box-office declines beyond a second weekend after release, the split mechanics as described have become increasingly less relevant to both distributors and exhibitors.

结果是,平均而言,参展商通常保留了美国近50%的票房收入(但在英国接近70%,在中国接近75%)。然而,考虑到如今许多电影在上映后的第二个周末之后票房迅速下降,所描述的分割机制对发行商和参展商来说越来越不重要。

As a result, the largest profit source (and about one-third of revenues) for many exhibitors is often not the box office but the candy, popcorn, and soda counter – where the operating margin may readily exceed 70% (and 90% on purposely salty popcorn). Theater owners have full control of proceeds from such sales; they can either operate food and beverage stands (and, increasingly, video games) themselves or lease to outside concessionaires. The importance of these concession profits to an exhibitor can be seen in the numerical example in Table 5.8. In addition, since the early 1980s, a third significant source of profit for theater operators is on-screen advertising, which generates margins of 90%. Together, concession sales and advertising might provide 75% of operating income for the typical multiplex (and, thus indirectly subsidize the cost of a ticket).48

因此,许多参展商的最大利润来源(约占收入的三分之一)往往不是票房,而是糖果、爆米花和苏打水柜台--营业利润率可能很容易超过70%(故意咸爆米花的营业利润率为90%)。剧院所有者完全控制这些销售的收益;他们可以自己经营食品和饮料摊位(以及越来越多的视频游戏),也可以出租给外部特许经营者。从表5 - 8的数值例子中可以看出这些特许权利润对投标人的重要性。此外,自20世纪80年代初以来,影院运营商的第三个重要利润来源是屏幕广告,利润率高达90%。特许权销售和广告加在一起可能为典型的多厅影院提供75%的营业收入(从而间接补贴门票成本)。48

Given the high percentage normally taken by the distributor, it is in the distributor’s interest to maintain firm ticket pricing, whereas it may be in the exhibitor’s interest to set low ticket prices to attract high-margin candy-stand patronage. In most instances, exhibitors set ticket prices and the potential for a conflict of interest does not present any difficulty to either party. But there have been situations (e.g., the releases of Superman, Annie, and a few Disney films) in which the distributor has suggested minimum per capita admission prices to protect against children’s prices that are too low. What distributors fear is that low admission prices will divert spending from ticket sales (where they get a significant cut) to the exhibitor’s concession sales.49

Although most theater operators will also attempt to enhance profitability through sales of advertising spots, some distributors (e.g., Disney since the early 1990s) may limit or bar exhibitors from showing advertisements before the film is run.50 Many such industry tactics and pricing practices – for example, why ticket prices for almost all films are pretty much the same no matter what film is being shown, or why popcorn at the concession stand is priced so high – have received empirical attention from economists.51

Release Strategies, Bidding, and Other Related Practices.

Large production budgets, high interest rates, and the need to spend substantial sums on marketing provide strong incentives for distributors to release pictures as broadly and as soon as possible (while also, incidentally, reducing the exhibitor’s risk). A film’s topicality and anticipated breadth of audience appeal will then influence the choice of marketing strategies that might be employed to bring the largest return to the distributor over the shortest time.52 Of greatest interest to the market research departments are a film’s marketability – how easily the film’s concept can be conveyed through advertising and promotion – and its playability, which refers to how well an audience reacts to the film after having seen it. Toward this end, trailers and advertising are key ingredients, with (and unlike for most other products) an average of around 70% of advertising spent prior to the film’s release date.

Many alternatives are available to distributors. Some films are supported with national network-television campaigns arranged months in advance, whereas others use only a few carefully selected local spots, from which it is hoped that strong word-of-mouth advertising will build. Sometimes a picture will be opened (limited release) in only a few theaters (i.e., playdates) in New York or Los Angeles during the last week of the year to qualify for that year’s Academy Award nominations and then later be taken into wide release of up to 3,000 national playdates (i.e., engagements/theaters).

Or, there may even be massive simultaneous saturation release on more than 3,000 screens at the seasonal peaks for which strategically important prospective dates (that purposely exclude World Cup and Olympic event periods) are staked out for up to five years ahead of time. Regional or highly specialized release is appropriate if a picture does not appear to contain elements of interest to a broad national audience. And simultaneous global release is now often used to thwart unauthorized copying.

或者,在季节性高峰期,甚至可能在3,000多个屏幕上同时进行大规模的饱和发布,其中具有重要战略意义的预期日期(故意排除世界杯和奥运会期间)提前五年。如果一幅图片似乎不包含全国广大观众感兴趣的内容,则应在区域或高度专业化的范围内发布。同时全球发布现在经常被用来阻止未经授权的复制。

In any case, different anti-blind bidding laws (laws that prohibit completion of contracts before exhibitors have had an opportunity to view the movies on which they are bidding) are effective in at least 23 states. These statutes were passed by state legislatures in response to exhibitor complaints that distributors were forcing them to bid on and pledge (guarantee) substantial sums for pictures they had not been given an opportunity to evaluate in a screening – in other words, buying the picture sight unseen. Distributors now generally screen their products well in advance of release, but large pledges from exhibitors may still sometimes be required for theaters to secure important pictures in the most desirable playing times, such as the week from Christmas through New Year’s. This is because not all weekends in the year are equally valuable and for these seasonal high periods theaters, might sometimes have to offer a substantial advance in nonrefundable cash against future rentals owed (i.e., guarantees).

在任何情况下,不同的反盲目投标法(禁止在放映商有机会观看他们投标的电影之前完成合同的法律)至少在23个州有效。这些法规是州立法机构通过的,以回应放映商的投诉,即经销商强迫他们为他们没有机会在放映中评估的照片出价并承诺(保证)大量资金-换句话说,购买未看到的照片。现在,发行商通常会在发行前提前对产品进行筛选,但有时仍需要放映商的大量承诺,以确保影院在最理想的播放时间(例如从圣诞节到新年的一周)放映重要影片。 这是因为并非一年中所有的周末都是同样有价值的,对于这些季节性的高峰期剧院,有时可能不得不提供一个不可退还的现金对未来的租金(即,保证)。

Whereas in theory movie releases from all studios can be expected to play in different houses depending only on the previously mentioned factors, some theaters, mostly in major cities, more often than not end up consistently showing the products of only a few distributors. Industry jargon denotes these as theater tracks or circuits. Tracks can evolve from long-standing personal relationships (many going back to before the Paramount consent decree) that are reflected in negotiated rather than bid licenses, or they may indicate de facto product-splitting or block-booking practices.53

理论上,所有电影公司的电影都可以在不同的影院上映,这仅仅取决于前面提到的因素,而一些影院,主要是在大城市,往往最终只会放映少数几个发行商的产品。行业术语将这些称为剧院轨道或电路。曲目可以从长期的个人关系(许多可以追溯到派拉蒙同意法令之前)演变而来,这些关系反映在谈判而不是投标许可证中,或者它们可能表明事实上的产品分割或区块预订做法。53

Product splitting occurs when several theaters in a territory tacitly agree not to bid aggressively against each other for certain films and with the intention of reducing average distributor terms. Each theater in the territory then has the opportunity, on a regular rotating basis, to obtain major new films for relatively low rentals percentages. Block booking, in contrast, occurs when a distributor accepts a theater’s bid on desirable films contingent on the theater’s commitment that it will also run the distributor’s less popular pictures.54

当一个地区的几家影院默认不为某些电影相互竞争,并有意减少平均分销商条款时,就会发生产品分割。本港每间戏院均有机会定期轮流以较低的租金比率取得新上映的大片。相反,当发行商接受影院对受欢迎电影的出价时,就会发生批量预订,前提是影院承诺也会经营发行商不太受欢迎的电影。54

As may be readily inferred, symbiosis between the exhibitor and distributor segments of the industry has not led to mutual affection. The growth of pay-per-view cable and the possibility of simultaneous domestic and foreign releases (known as day and date in the industry) in video and Internet-related formats may further strain relations. As Reference De Vany and WallsDe Vany and Walls (1997) have noted, the legal constraints stemming from the Paramount decree have prevented multiple-picture licensing so that

可以很容易地推断,该行业的分销商和分销商之间的共生关系并没有导致相互影响。按次付费有线电视的增长以及国内和国外同时以视频和互联网相关格式发布的可能性(业内称为日期和日期)可能会进一步加剧关系。正如De Vany和Walls(1997年)所指出的,源自派拉蒙法令的法律的限制阻止了多画面许可,

[N]o contracts can be made for the whole season of a distributor’s releases, nor for any portion of them. Nor is it possible to license a series of films to theaters as a means of financing their production. The inability to contract for portfolios of motion pictures restricts the means by which distributors, producers and theaters manage risk and uncertainty.

[N]o合同可以针对发行商发行的整个季节,也可以针对其中的任何部分。也不可能将一系列电影许可给剧院作为资助其制作的手段。无法签订电影组合合同,限制了发行商、制片人和影院管理风险和不确定性的手段。

Exhibition Industry Characteristics. (a) Capacity and Competition.

展览行业特点。(a)能力与竞争。

The long-run success of an exhibition organization is highly dependent on its skill in evaluating and arranging real estate transactions. Competition for high-traffic locations (which raises lease payment costs) and the presence of too many screens relative to the size of a territory will generally reduce overall returns.

一个展览机构的长期成功在很大程度上取决于其评估和安排真实的房地产交易的技能。对高流量地点的竞争(这会提高租赁支付成本)以及相对于领土面积而言过多屏幕的存在通常会降低整体回报。

To achieve economies of scale, since the 1960s exhibitors have tended to consolidate into large chains operating multiple screens located near or in shopping-center malls. Meanwhile, older movie houses in decaying city-center locations have encountered financial hardships as the relatively affluent consumers born after World War II have grown to maturity in the suburbs, and as crime and grime and scarcity of parking spaces have often become deterrents to regular moviegoing by city residents.55

为了实现规模经济,自20世纪60年代以来,参展商倾向于合并成大型连锁经营多个屏幕位于附近或在购物中心商场。与此同时,随着二战后出生的相对富裕的消费者在郊区逐渐成熟,以及犯罪、污垢和停车位的稀缺往往成为城市居民经常去看电影的障碍,位于衰败的市中心地区的老电影院遇到了财政困难。55

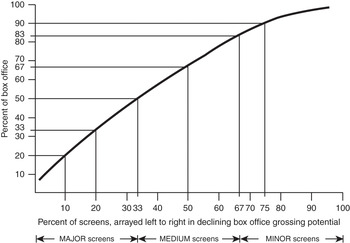

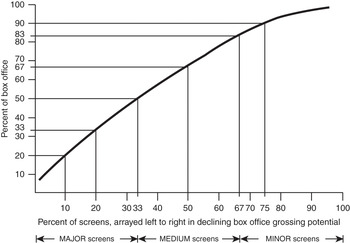

In 2018 there were approximately 40,000 screens, a diminishing proportion of which were drive-ins and a growing percentage of which were in the giant screen (100 feet wide and 80 feet high) IMAX format that was initially developed for museums and that is especially effective for exhibiting (both in 2D and 3D) sci-fi, fantasy, and historical epics. Such large screens, known as premium large format (PLF), are also being built by conventional theater chains. The total number of screens has been increasing since 1980 at an average rate of 2.2%, with box-office gross per screen rising an average 1.7% per year (see Table 3.3). During this time operating incomes and market shares for large, publicly owned theater chains running so-called megaplexes of at least 12 screens at one location have obviously gained rapidly at the expense of single-theater operators. For example, as of 1982, the top-grossing third of screens generated half of the box office, with the bottom third generating about one-sixth of the box office (Reference Murphy and SquireMurphy 1983 and Figure 4.4). Currently, the top one-third of screens probably account for at least 75% of all theater grosses.

2018年,大约有40,000个屏幕,其中驱动器的比例越来越小,其中越来越多的比例是巨型屏幕(100英尺宽,80英尺高)IMAX格式,最初是为博物馆开发的,对于展示(2D和3D)科幻,幻想和历史史诗特别有效。这种大屏幕,被称为优质大格式(PLF),也正在由传统的连锁影院建造。自1980年以来,银幕总数以平均2.2%的速度增长,每块银幕的票房总额平均每年增长1.7%(见表3.3)。在这段时间里,经营收入和市场份额的大型,公有的连锁影院运行所谓的巨型至少12屏幕在一个位置显然获得了迅速牺牲单一影院运营商。 例如,截至1982年,票房收入最高的三分之一的屏幕产生了一半的票房,而票房收入最低的三分之一产生了大约六分之一的票房(墨菲,1983和图4 - 4)。目前,前三分之一的屏幕可能占所有影院票房的至少75%。

Figure 4.4. Domination of box-office performance by key U.S. movie theaters.

图4.4. 美国主要电影院主导票房表现。

资料来源:Variety,1982年7月7日。1982年,A。D.墨菲

Although the number of screens in North America has been increased substantially (Figure 4.3b), the number of separate theater locations has not grown by nearly as much because many locations have been multiplexed. It is now, accordingly, more difficult to “platform” a film because there are essentially only two types of theaters: first-run multiple-screen houses and all others. Previously, there had been at least three tiers of theater quality, ranging from first-run fancy to last-run, small neighborhood “dumps.”

虽然北美的银幕数量已经大幅增加(图4.3 b),但独立影院的数量却没有增长那么多,因为许多影院都是多路复用的。因此,现在更难“平台”一部电影,因为基本上只有两种类型的影院:首轮放映的多屏幕影院和所有其他影院。在此之前,至少有三个层次的剧院质量,从第一轮花式到最后一轮,小社区“垃圾场”。

Even if a film has “legs” (i.e., strong popular appeal so that it runs a long time), the maximum theoretical revenue R is a function of the average length of playing time T, the number of showings per day N, the average number of seats per screen A, the number of screens S, the average ticket price P, and audience suitability ratings (G, PG, PG-13, R, NC-17/X), which also influence the potential size of the audience.56

即使一部电影有“腿”(即,强的流行吸引力,从而它运行很长时间),最大理论收入R是播放时间T的平均长度、每天放映的次数N、每个屏幕的平均座位数A、屏幕数S、平均票价P和观众适合性等级(G、PG、PG-13、R、NC-17/X)的函数,其也影响观众的潜在规模。56

R=P ×N ×A ×S,

其中N=f(T)。

For example, if the average ticket price is $10, the average number of showings per day is four, the average number of seats per theater is 300, and the number of screens is 500, the picture can theoretically gross no more than $6 million (10 × 4 × 300 × 500) per day, or $42 million per week. This type of analysis is of interest to distributors as comparisons are made to the potential of pay-per-view cable release, from which there is the possibility to earn, on a $4-per-view charge, at least $20 million overnight.57

例如,如果平均票价为10美元,每天平均放映次数为4次,每个影院的平均座位数为300个,屏幕数为500个,那么理论上这部电影每天的票房收入不超过600万美元(10 × 4 × 300 × 500),即每周4200万美元。这种类型的分析是感兴趣的分销商,因为比较的潜力,按次付费有线电视释放,有可能赚取,每4美元的收视费,至少2 000万美元的夜晚。57

Because the preceding figures used in calculating a theoretical weekly total gross for a single picture are about average for the whole industry, they can also be used to estimate an aggregate for all exhibitors. Following this line, it can be determined that in 2018, the maximum theoretical annual gross, based on 40,600 screens, was about $292 million per day, or about $107 billion per year. The industry obviously operates well below its theoretical capacity, because there are many parts of the week and many weeks of the year during which people do not have the time or inclination to fill empty theater seats: That is, weekends usually account for an estimated 70% of box-office revenues. In 2018 the industry’s average occupancy rate per seat per week was roughly 2.1 times, thus only 6.0% of theoretical capacity.

由于上述用于计算一张图片的理论周总收入的数字大约是整个行业的平均值,因此它们也可以用于估计所有参展商的总收入。根据这条线,可以确定,在2018年,基于40,600块屏幕的最大理论年总收入约为每天2.92亿美元,即每年约1070亿美元。电影业的运作显然远低于其理论容量,因为一周中的许多时间和一年中的许多周,人们没有时间或意愿去填补剧院的空座位:也就是说,周末通常占票房收入的70%。2018年,该行业每周每个座位的平均上座率约为2.1倍,仅为理论载客量的6.0%。

For the major film releases most likely to be opened during peak seasons, calculations of this kind do not actually have much relevance because there are no more than about 12,000 quality first-run screens, of which perhaps only 4,000 can normally be simultaneously booked. By far the most important effect of severe competition for quality playdates in peak seasons is that marketing budgets must be raised to levels much higher than they would otherwise be (and for economic reasons explained in Section 1.3). In such an environment, modestly promoted films, even those of high artistic merit, may have little time to build audience favor before they are pulled from circulation.58

对于最有可能在旺季上映的主要电影,这种计算实际上没有多大意义,因为只有大约12,000个高质量的首轮放映屏幕,其中可能只有4,000个通常可以同时预订。到目前为止,在旺季对高质量游戏日期的激烈竞争的最重要的影响是,营销预算必须提高到比其他情况高得多的水平(以及1.3节中解释的经济原因)。在这样的环境下,适度宣传的电影,即使是那些具有很高艺术价值的电影,在它们被撤出流通之前,可能几乎没有时间建立观众的好感。58

In comparing the popularity of different films in different years, most media reports merely show the box-office grosses: Film A did $10, and film B did $11; therefore B did better than A. In addition, a deeper, but still often misleading, comparison is sometimes derived by calculating an average gross per screen (which is often misinterpreted and is actually per location). Close analysis and comparison of box-office data require that variables such as ticket-price inflation, film running time, season, weather conditions, number and quality of theaters, average seats per theater, and types of competing releases be considered.59

在比较不同电影在不同年份的受欢迎程度时,大多数媒体的报道仅仅显示了票房收入:电影A卖了10美元,电影B卖了11美元;因此B卖得比A好。此外,更深层次的,但仍然经常误导,比较有时是通过计算每个屏幕的平均毛(这往往是误解,实际上是每个位置)。对票房数据的密切分析和比较需要考虑诸如票价通胀、电影放映时间、季节、天气条件、影院数量和质量、每家影院的平均座位以及竞争上映的类型等变量。59

(b) Rentals Percentage. (b)租金百分比。

All other things being equal, when the supply of films is small compared with exhibitor capacity, the percentage of box office receipts reverting to distributors (the rentals percentage) rises.60 Faced with a relatively limited selection of potentially popular pictures, theater owners tend to bid more aggressively and to accede to stiffer terms than they otherwise would. Especially in the late 1970s, for example, there were loud complaints by exhibitors of “product shortage” as the total number of new releases and reissues declined by 43% to 110 in 1978 from the preceding 1972 peak of 193. As might be expected, distributor rentals percentages (and thus profit margins) were high in the late 1970s (Table 3.3 and Figure 4.3c).

在其他条件相同的情况下,当电影供应量与发行商的产能相比很小时,票房收入中返还给发行商的比例(租金比例)就会上升。60面对相对有限的潜在受欢迎的电影,剧院业主往往会更积极地出价,并同意比他们更严格的条款。特别是在20世纪70年代末,例如,有响亮的投诉,参展商的“产品短缺”的总数量新发行和再版下降了43%,从1972年的193个高峰下降到1978年的110。正如所料,20世纪70年代后期分销商的租金比例(以及利润率)很高(表3.3和图4.3 c)。

To some extent, however, the rentals percentage also depends on ticket prices and on how moviegoers respond to a year’s crop of releases. A poorly received crop tends to reduce the average distributor rentals percentage as floor (minimum) clauses on contracts with exhibitors are activated, as advances and guarantees are reduced in size and number, and as settlements are more often required. Even important releases now tend to have only one or two weeks of box-office presence before fading and thereby denying theaters the higher percentages that would be earned if pictures were to play more strongly over more weeks, as they had often done prior to the late 1990s.

然而,在某种程度上,租金百分比也取决于票价和观众对一年的电影发行量的反应。由于与参展商签订的合同中的最低(最低)条款被激活,由于预付款和担保的规模和数量减少,以及由于更经常地需要结算,收到的收成不佳往往会降低平均经销商租金百分比。现在,即使是重要的电影上映,也往往只有一两周的票房表现,然后就会消失,从而剥夺了电影院在更长时间内播放更强劲的电影所能获得的更高比例,就像20世纪90年代末之前经常做的那样。

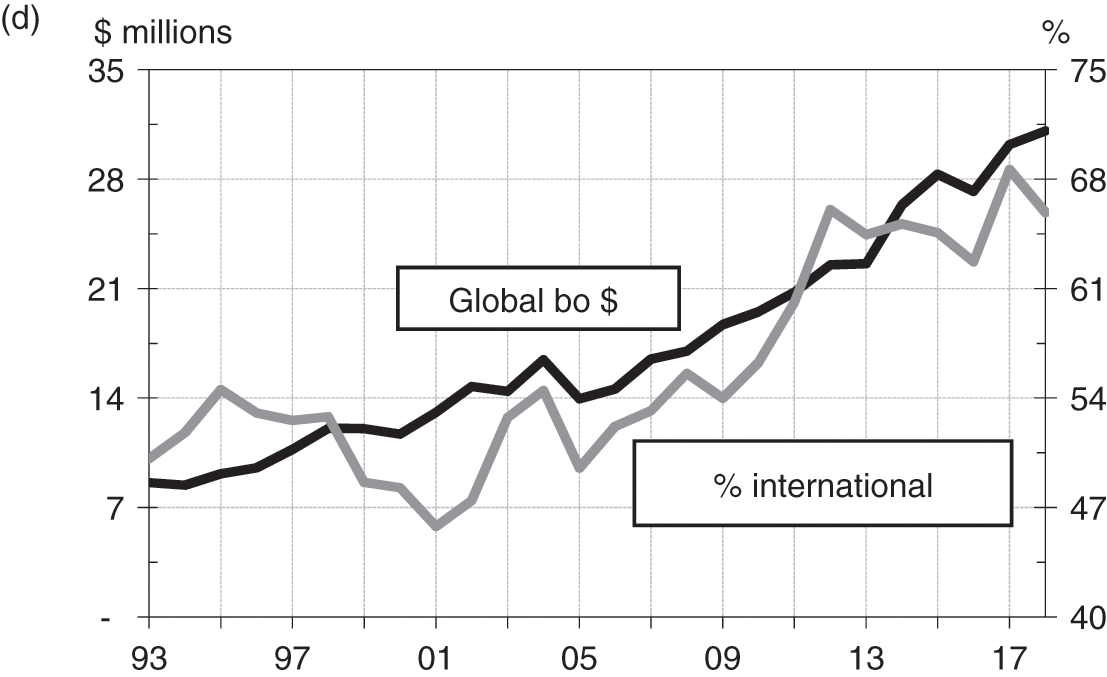

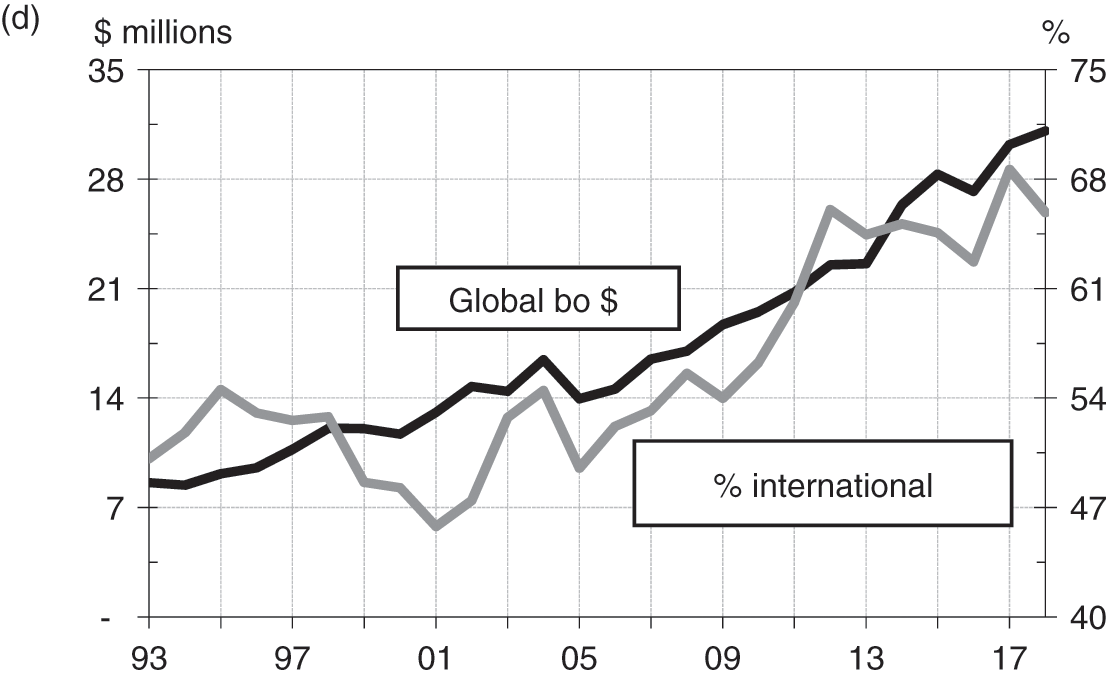

Although theatrical exhibition is inherently volatile over the short run, over the longer run there is nevertheless a remarkable consistency in the way the domestic business behaves. Since the 1960s, in a typical week approximately 8% to 10% of the U.S. population buys admission to a movie. And as can be seen in Figure 4.5a, the top 20 grossing films of any year will normally account for an average of around 40% of that year’s box-office total, with a giant hit every so often temporarily boosting the percentage. Figure 4.5b meanwhile suggests that the variance of results for the top 20 is not large and that growth in constant dollars has been modest. The long-term per capita admissions trend is depicted in Figure 4.5c, and Figure 4.5d shows that the top 100 films of any year have been consistent in drawing more than half of their total box-office income in foreign markets.

虽然戏剧展览在短期内具有内在的波动性,但从长期来看,国内商业的行为方式仍然具有显着的一致性。自20世纪60年代以来,在典型的一周内,大约有8%到10%的美国人购买电影入场券。从图4.5(a)中可以看出,任何一年票房收入最高的20部电影通常平均占当年总票房的40%左右,偶尔会有一部巨大的成功暂时提高这一比例。同时,图4.5 b表明,前20名企业的业绩差异并不大,以定值美元计算的增长也很温和。图4.5 c描绘了长期的人均入场趋势,图4.5 d显示,任何一年的前100部电影都一直在外国市场吸引超过一半的票房收入。

Figure 4.5. (a) Top 20 films, domestic box-office gross, 1982–2018, (b) Top 20 films, domestic box-office gross, constant dollar mean and variance, 1980–2018, (c) Approximate U.S. per capita theater admissions, 1965–2018, (d) Top 100 films, domestic and foreign gross comparisons, 1993–2018. (cont.)

图4.5. (a)1982-2018年美国国内票房总收入前20名;(B)1980-2018年美国国内票房总收入前20名,不变美元平均值和方差;(c)1965-2018年美国人均影院入场人数;(d)1993-2018年美国国内和国外票房总收入前100名。(注:)

Figure 4.5. (cont.)

图4.5. (注:)

Video, Output Deals, and Merchandising

视频、输出交易和广告

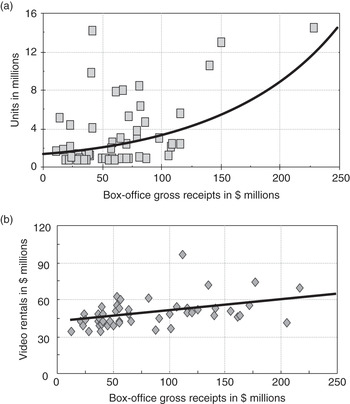

Video. 视频.

Until the 1980s, moviemakers both large and small were primarily concerned with marketing their pictures in theaters. But starting in 1986, distributors generated more in domestic wholesale gross revenues from home video (about $2 billion) than from theatrical ($1.6 billion) sources. Home video thus forever altered the fundamental structure of the business and changed the ways in which marketing strategies are pursued.61

直到20世纪80年代,大大小小的电影制作人主要关心的是在影院推销他们的电影。但从1986年开始,分销商从家庭视频(约20亿美元)中获得的国内批发总收入超过了戏剧(16亿美元)。因此,家庭录像永远地改变了企业的基本结构,改变了营销策略的实施方式。61

Digital video disc players (DVDs) have been familiar items in households around the world and have had great impact since being introduced in 1997. And because of the enormous installed base and royalty distribution rather than percent of film rental accounting, they remain an important (but now diminishing) funds-flow and profits engine for filmmakers.62

数字视频光盘播放器(DVD)已经成为世界各地家庭的常见物品,自1997年推出以来产生了巨大的影响。由于巨大的安装基础和版税分配,而不是百分之电影租赁会计,他们仍然是一个重要的(但现在正在减少)资金流和利润引擎的电影制片人。62

With the profit per unit on a DVD around twice as high as that on a tape, studios have had an incentive to return to the simple consumer purchase model that has long been used in the recorded music business.63 DVDs undermined the rental tape-pricing model (as well as the revenue-sharing model) that had carried the home video industry through its first 20 years. DVDs, moreover, caused a shift of profitability structure toward one more favorable to studios (now able to retain a comparatively larger portion of a film’s total revenues than with exhibitors).

由于DVD的每单位利润大约是磁带的两倍,制片厂有动力回到简单的消费者购买模式,这种模式长期以来一直用于录制音乐业务。63DVD破坏了租赁磁带定价模式(以及收入共享模式),该模式支撑了家庭视频行业的前20年。此外,DVD还导致了盈利结构向更有利于制片厂的方向转变(与放映商相比,现在能够保留电影总收入的相对较大部分)。